47 Traction

Types of Distraction

Inhibitory or inhibitive distraction is compression placed over muscles or tendons of insertion, while the joint underneath is stretched.1 An example of this is subcranial distraction. This type of distraction is based on the theory that pressure on the origin or insertion of a muscle fires the Golgi tendon apparatus (GTO) which, as a result, relaxes the muscle. With the muscles relaxed (inhibited), they do not resist the stretch being applied to the underlying joints.

Positional traction by Paris2 is most useful in the spine where two vertebrae are so positioned that the intervertebral foramen between them opens to relieve nerve root pressure. The patient lies over pillows and perhaps is held or assisted by straps.

The three-dimensional mechanical traction table allows positioning of the patient such that the traction force results in a distraction at the spinal level and the side that is desired. The most recent traction tables are designed by Kaltenborn, Paris, and others.2

Therapeutic Effects

When performed correctly, cervical and lumbar traction can cause many effects such as distraction or separation of vertebral bodies; a combination of distraction and gliding of the facet joints; tensing of the ligamentous structures of the spinal segment; widening of the intervertebral foramen; straightening of the spinal curves; and stretching of the spinal musculature.3 Some practitioners believe fluid exchange occurs within the spinal disc during traction.4

It is generally accepted that cervical and lumbar traction can be helpful in centralizing a pain process and in reducing radicular symptoms.5–8 Xin9 suggests that cervical traction helps with vertebrobasilar insufficiency resulting from spondylosis when combined with enhanced external counterpulsation. Others believe more definitive studies are needed to fully understand the benefits of traction.10,11

Sustained or Intermittent Mechanical Traction and Manual Traction

Keep in mind that traction is a force and not a result.1 Results of sustained or intermittent mechanical traction include: (1) foraminal distraction; (2) flattening of any disc bulge; (3) relief of pressure on the nerve root. Conversely, manual traction can be sustained only for a short period of time. The techniques are often much stronger than mechanical traction techniques and the results include stretch to the myofascia; stretch to facet capsules; and occasional repositioning of vertebrae.

Clinical Studies

Katavich,12 indicated in her research, that a stretch generated in cervical muscles and skin during cervical traction has the potential to influence the excitability of motor neurons. She believes manual cervical traction relieves pain and muscle spasm in the neck and upper quartile. In her study, she postulated that afferent input generated by these procedures may lower the excitability of X motor neurons of upper limb muscles. Therefore, an understanding of the receptors and mechanisms underlying manual therapy may allow more effective stimulation, and hence, improved clinical outcomes.

Briem,13 and others, have evaluated the immediate effects of inhibitive distraction on active range of cervical flexion in patients with neck pain. This study did not confirm the immediate effects of inhibitive distraction on cervical flexion AROM, but did provide indications for potential subgroups likely to benefit from this technique. Cai14 described positive predictors for lumbar traction to be noninvolvement of manual work, low-level fear avoidance beliefs, absence of neurologic deficits, and age >30 years. Raney15 described positive predictors for cervical traction to be when the patient reports peripheralization with lower cervical spine (C4-7) mobility testing, positive shoulder abduction test, age ≥55 years, positive upper limb tension test, and positive neck distraction test.

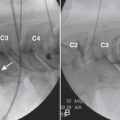

Creighton16 confirmed the merits of positional distraction as a means to open the lumbar neuroforamen. A lateral radiograph was taken of the left lumbar neuroforamen in 10 subjects. The average foraminal opening was >4 mm at L3, L4, and L5. It is possible that even greater opening could have been achieved if towel rolls had been individually fitted—as is done in the clinical setting. Both supine and prone lumbar traction should be attempted to maximize traction benefits.17

Contraindications for Spinal Traction

Traction is known to be a safe procedure with therapeutic value in helping patients with spine-related pain. It is recommended that a detailed history, physical examination, and radiologic studies be performed prior to implementing cervical and lumbar traction techniques. Although the literature is lacking in studies reporting clear contraindications to traction, the clinician must rely on empirical information and opinion. These contraindications include (1) ligamentous instability (prior trauma or rheumatoid arthritic patients); (2) spinal infections, such as osteomyelitis, or discitis; (3) severe osteoporosis or osteopenia; (4) primary bone or spinal cord and metastatic tumors; (5) myelopathies; (6) uncontrolled hypertension or vertebral basilar artery insufficiency (for cervical traction);18 (7) the very young and the very old frail patients; and (8) acute or subacute spinal fractures. Relative contraindications for lumbar traction include pregnancy, abdominal or inguinal hernias, and aortic aneurysms.

Cervical Traction Techniques

Inhibitive Distraction

Subcranial inhibitive distraction is a myofascial technique described by Paris2 that is aimed at releasing tension in suboccipital soft tissue and suboccipital musculature. The patient lies supine with head supported. The physical therapist places the three middle fingers just caudal to the nuchal line, lifts the finger tips upward resting the hands on the treatment table, and then applies a gentle cranial pull, causing a long axis extension. The procedure is performed for 2 to 5 minutes (see Fig. 47-1).

Manual Cervical Traction Following Inhibitive Distraction

The patient lies supine with head supported. The physical therapist places six finger tips, facing vertically and placed along the base of the occiput just distal to the muscular insertions but proximal to the atlas. The technique is divided into two stages: (1) the hands are drawn slightly toward the clinician until the head tilts out of the hands and rests exclusively on the finger tips (see Fig. 47-2); (2) the physical therapist now brings the front of the patient’s shoulder to contact the patient’s forehead. The patient is now held firmly between the six fingers and front of the shoulder. The physical therapist now imparts a longitudinal traction to the cervical spine (see Fig. 47-3).

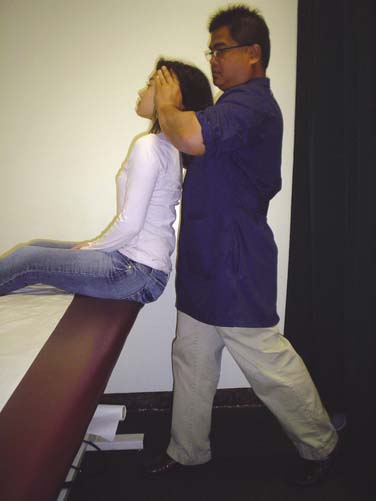

Manual Cervical Traction in Sitting Position

The patient is seated on an adjustable-height table that allows the therapist to bring the patient close to the clinician. The therapist stands on a diagonal behind the patient. The arms are rested at the side of the patient’s mastoid processes and the palms of the hand are cupped (see Fig. 47-4). The clinician leans back, keeping the hands at a constant height from the floor. Traction is applied due to the increasing distance between the mastoids that are moving backwards, and the ischial tuberosities that are remaining stable (see Fig. 47-5).

Positional Cervical Distraction

Patient is instructed to lie supine. Patient is then instructed to raise head and neck until slack of forward bending is removed form the level to be distracted. Head is supported (e.g., on a firm stack of books). The radial border of one hand forms a fulcrum that is placed opposite the foramen to be opened. The neck is then bent over the hand. Static or intermittent traction may now be applied (see Fig. 47-6). Patient can try following through with this technique at home for 20 minutes twice a day.

Over-the-Door Cervical Traction (Fig. 47-7)

Preparing for Treatment

Applying Traction

Mechanical Traction (Saunders Cervical Traction)

Preparing for Treatment

Applying the Traction

Lumbar Traction Techniques

Positional Distraction

To facilitate lumbar positional distraction, the following steps are followed14: (1) a firm bolster is made up of pillow and sheet and placed at the level of iliac crest; (2) the bolster is placed opposite the level at which maximum side-bending is desired; (3) both legs are then bent forward at the hip and knees to bring the opening to desired level; (4) the spine is now rotated at the level above where the maximal opening is desired; (5) the patient is now in positional distraction (see Fig. 47-9); (6) a belt may be added to help maintain the position. Initially, treatment time is not more than 5 minutes on the first day. Gradually increase the treatment duration in 5- to 10-minute increments until a 40-minute regimen is attained.

Mechanical Traction (Saunders Lumbar Traction)

Preparing for Treatment

Applying Traction

Amount of Force to Produce Spinal Traction

In the lumbar spine, it has been reported that 120 lb for 15 minutes is necessary to produce a structural change (movement) at the spinal segment.3 A force equal to one-half of the patient’s body weight on a friction-free surface is thought to be a minimum to cause therapeutic effects in the lumbar spine.3 However, a therapeutic effect may occur with less than one half of the body weight. Therefore, it is important to document patient’s reaction and results of treatment per visit. Adjustments can be made to achieve maximum results.

In the cervical spine, it has been shown that 25 to 45 lb forces were necessary to demonstrate a measurable change in the posterior cervical spine structures and separation of the intervertebral discs.3 Changes at the atlantooccipital and atlantoaxial joints with 10 lb of traction have been noted.3 Less force appears necessary to produce separation in the upper cervical spine.

Ligamentous rupture in the lumbar spine has been described in cadaveric studies with 880 lb of force, thoracolumbar spine with 400 lb of force, and 120 lb in cervical spine (disc rupture).3

1. Paris S.V.P. S3 Seminar Manual Cervical Evaluation and Manipulation, 4th ed. St. Augustine, Fla: Paris, Inc; 2000. 94

2. Paris S.V.P. S1 Seminar Manual Extremity Evaluation and Manipulation, 2nd ed. St. Augustine, Fla: Institute of Graduate Physical Therapy; 1991. 99, 197

3. Saunders H.D., Saunders R. Evaluation, Treatment, and Prevention of Musculoskeletal Disorders, 3rd ed. Chaska, Minn: Educational Opportunities; 1995. 281–289, 298

3a. Catapang G.P. Tracking the causes of chronic pain. Advance for Directors in Rehabilitation. June 2008:57.

3b. Huang Z.J., Chen J.X., Qi W.W. Clinical research on treatment of vertebroarterial type of cervical spondylosis with 5 step manipulation and traction. J Tradit Chin Med. 2009;29(4):268-270.

3c. Paris S.V.P., Loubert P.V. Foundations of Clincial Orthopedics, 3rd ed. St. Augustine, Fla: Institute Press; 1999. 342

4. Cholewicki J., Lee A.S., Reeves N.P., Calle E.A. Trunk muscle response to various protocols of lumbar traction. Man Ther. 2009;14(5):562-566.

5. Jellad A., Ben Salah Z., Boudokhane S., et al. The value of intermittent cervical traction in recent cervical radiculopathy. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2009;52(9):638-652.

6. Moeti P., Marcheti G. Clinical outcome from mechanical intermittent cervical traction for the treatment of cervical radiculopathy: A case series. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2001;31(4):207-213.

7. Olivero W.C., Dulebohn S.C. Results of halter cervical traction for the treatment of cervical radiculopathy; retrospective review of 81 patients. Neurosurg Focus. 12(2), 2002 Feb 15.

8. Swezey R.L., Swezey A.M., Warner K. Efficacy of home cervical traction therapy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;78(1):30-32.

9. Xin W., Fangjian G., Hua W., et al. Enhanced external counterpulsation and traction therapy ameliorates rotational vertebral artery flow insufficiency resulting from cervical spondylosis. Spine. 2010;35:1415-1422.

10. Graham N., Gross A.R., Goldsmith C. Mechanical traction for mechanical neck disorders: A systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2006;38(3):145-152.

11. Graham N., Gross A., Goldsmith, et al. Mechanical traction for neck pain with or without radiculopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 16(3), 2008. CD006408

12. Katavich L. Neural mechanisms underlying manual cervical traction. J Orthop ManipTher. 1999;7(1):20-25.

13. Briem K., Huijbregts P., Thorseteinsdottir M. Immediate effects of inhibitive distraction on active range of cervical flexion in patients with neck pain: A pilot study. J Man Manip Ther. 2007;15:82-92.

14. Cai C., Pua Y.H., Lim K.C. A clinical prediction rule for classifying patients with low back pain who demonstrate short-term improvement with mechanical lumbar traction. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(4):554-561.

15. Raney N.H., Petersen E.J., Smith T.A., et al. Development of a clinical prediction rule to identify patients with neck pain likely to benefit from cervical traction and exercise. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(3):382-391.

16. Creighton D. Positional distraction, a radiological confirmation. J Orthop Manip Ther. 1993;1(3):83-86.

17. Beattie P.F., Nelson R.M., Michener L.A., et al. Outcomes after a prone lumbar traction protocol for patients with activity-limiting low back pain: A prospective case series study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(2):269-274.

18. Reyes T. Introduction to Physical Therapy and Patient Care, Hyrotherapy, Traction, and Massage, 2nd ed. Manila, Philippines: UST Press; 1985. 121