26 Sciatic Nerve Block

Anatomy

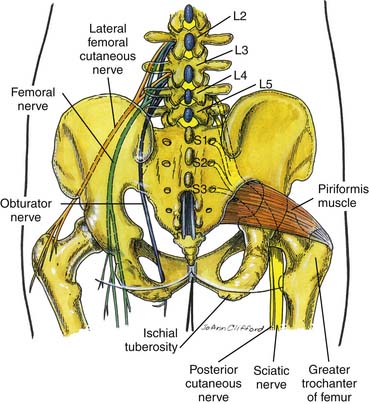

The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the body and is found in the pelvis from the ventral rami of the fourth lumbar to the third sacral spinal nerves.1 It transverses through the sciatic foramen and below the piriformis to enter the lower extremity and then descends between the greater trochanter and the ischial tuberosity (Fig. 26-1). In some cases the common peroneal component may pass through the piriformis, whereas the tibial component passes below the muscle.

History

Historically, the sciatic nerve block was first described by Victor Pauchet in 1920. In 1923, a similar approach was described by Gaston Labat in his book, Regional Anesthesia: Its Technique and Clinical Application. In 1975, Alon Winnie described the “modified Labat” technique. The anterior approach to the sciatic nerve block was described by Beck. In 1993, Mansour described the parasacral approach to the sacral plexus.2 Di Beneditto and colleagues described the subgluteal approach to the sciatic nerve block in 2001.3

Indications for Sciatic Nerve Block

Sciatic nerve block is indicated for lower limb surgery including surgery on the knee, ankle, and foot. A lumbar plexus block is beneficial for hip surgery. Various studies have demonstrated the benefits of continuous popliteal (sciatic nerve) block for postoperative pain control after painful orthopedic foot surgery. The benefits include decreased pain, reduced opioid requirements and opioid-related adverse effects.4–6 Sciatic nerve block may be a useful adjunct for certain lower extremity chronic pain syndromes such as sciatic neuropathy or piriformis syndrome where there is compression of the sciatic nerve at the piriformis muscle.

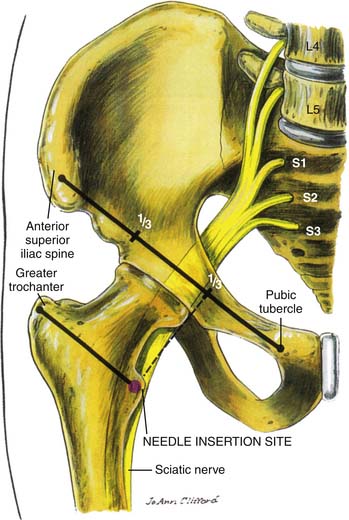

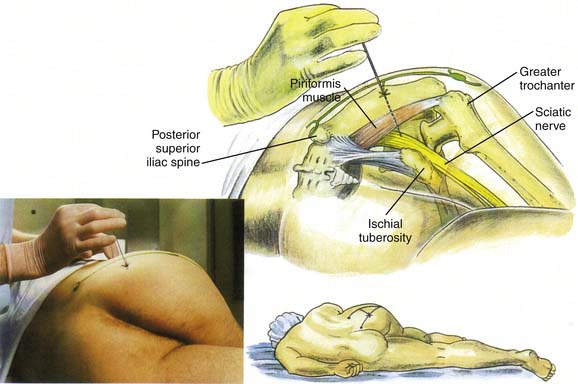

Sciatic Nerve Block—Posterior Approach

The needle insertion site is 4 cm below the midpoint of the line joining the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) to the ipsilateral greater trochanter (Fig. 26-2). The needle is inserted perpendicular to the skin. A nerve stimulator with a standard setting of 2 Hz and 100 μsec can be used and will initially cause a twitching of the gluteal muscles. On further advancement of the needle and with stimulation of the sciatic nerve, contraction of the hamstrings and calf muscles will be noted. This is observed as dorsiflexion of the ankle and foot. Small adjustments of the needle may become necessary to achieve stimulation at less than 0.5 mA. The stimulation current may be reduced until disappearance of stimulation is noted. This should usually be above 0.2 mA. After initial and intermittent negative aspiration 15 to 30 mL of local anesthetic is injected in increments of 4 to 5 mL. Injection of local anesthetic should be without any resistance and without pain or paresthesia. Triamcinolone (40 to 80 mg) or other corticosteroid with a lower volume of local anesthetic can be added when used for treatment of chronic pain syndromes.

Figure 26-2 Sciatic nerve block: posterior approach.

(From Brown DL: Atlas of Regional Anesthesia, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2005.)

In situations where prolonged postoperative analgesia is required, a catheter is threaded 5 to 10 cm beyond the needle tip and left in situ. Prior to injecting local anesthetic through the catheter, it should always be aspirated to confirm that the catheter tip is not intravascular.

Sciatic Nerve Block—Anterior Approach

The femoral artery is palpated within the femoral crease. From this point, a line is drawn perpendicular to the femoral crease to identify a point 5 cm distal to the femoral crease (Fig. 26-3). At this point, a needle is inserted perpendicular to the skin plane. A nerve stimulator with a standard setting of 2 Hz and 100 μsec can be used and will initially cause contraction of the quadriceps muscles. On further advancement of the needle and stimulation of the sciatic nerve, contraction of the hamstrings and calf muscles will be noted. Make small adjustments of the needle if necessary to achieve stimulation at less than 0.5 mA. Continue to reduce the stimulation current until the contraction disappears. This should usually be above 0.2 mA. After initial and intermittent negative aspiration of blood 15 to 30 mL of local anesthetic can be injected in increments of 4 to 5 mL. Injection of local anesthetic should be without any resistance and without pain or paresthesia. If bone was contacted prior to obtaining the desired stimulation, the needle can be reinserted medially. Triamcinolone (40 to 80 mg) or other corticosteroid with a lower volume of local anesthetic can be added when used for treatment of chronic pain syndromes.

Lumbar Plexus Block—Parasacral Approach

The parasacral approach to a lumbar plexus block was described by Mansour in 1993.7 This block can be used for anesthesia and analgesia in patients having lower extremity hip, tibia and fibula, knee, ankle, and foot surgery and amputation at the level of the knee.8

A line is drawn connecting the posterior-superior iliac spine and the ischial tuberosity. On this line, the needle is inserted 6 cm from the posterior superior iliac spine and advanced in the sagittal plane. A nerve stimulator with a standard setting of 2 Hz and 100 μsec can be used and will cause a contraction of the hamstring and posterior leg muscles. Make small adjustments of the needle position if necessary to achieve stimulation at less than 0.5 mA. Continue to reduce the stimulation current until the contraction disappears. This should usually be above 0.2 mA. After initial and intermittent negative aspiration 15 to 30 mL of local anesthetic can be injected in increments of 4 to 5 mL. Injection of local anesthetic should be without any resistance and without pain or paresthesia. If bone was contacted prior to obtaining desired stimulation, the needle should be redirected caudally. Triamcinolone (40 to 80 mg) or other corticosteroid with a lower volume of local anesthetic can be added when used for treatment of chronic pain syndromes.

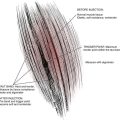

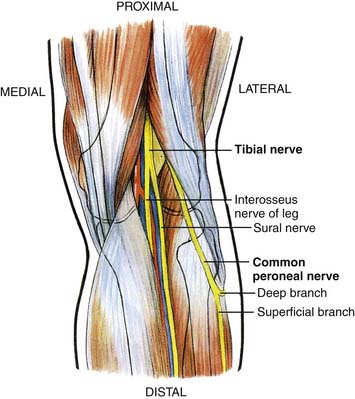

Sciatic Nerve Block at the Popliteal Fossa

The sciatic nerve consists of two separate nerve trunks—the tibial and common peroneal nerves (Fig. 26-4). These nerves share a common epineural sheath and are separated throughout their course by a thin fascial plane. In the popliteal fossa, the tibial and common peroneal nerves diverge. The level of this separation is highly variable and occurs from 5 to 12 cm proximal to the popliteal crease.9 The common peroneal nerve continues behind the fibular head and divides into the superficial and deep peroneal nerves. The superficial peroneal nerve innervates the lateral compartment muscles of the leg (peroneal longus and brevis). The deep peroneal nerve innervates the anterior compartment muscles of the leg. The tibial nerve travels down in the posterior aspect of the leg with the posterior tibial artery. During its course, it gives rise to the medial sural cutaneous and medial calcaneal branches. The tibial nerve terminates as the medial and lateral plantar nerves.

Figure 26-4 Sciatic nerve anatomy in the popliteal fossa.

(From Brown DL: Atlas of Regional Anesthesia, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2005.)

These landmarks are clearly identified and marked by asking the patient to flex the leg at the knee. The needle can be inserted at the midpoint between the tendons about 7 to 10 cm proximal to the popliteal crease. A nerve stimulator with a standard setting of 2 Hz and 100 μsec can be used. Stimulation of the common peroneal nerve will result in dorsiflexion and eversion at the ankle, whereas stimulation of the tibial nerve results in plantar flexion and inversion at the ankle. Either of these responses is acceptable. Make small adjustments of the needle if necessary to achieve stimulation at less than 0.5 mA. Continue to reduce the stimulation current until the contraction subsides. This should usually be above 0.2 mA. After initial and intermittent negative aspiration, 25 to 30 mL of local anesthetic is injected in increments of 4 to 5 mL. Injection of local anesthetic should be without any resistance and without pain or paresthesia. Triamcinolone (40 to 80 mg) or other corticosteroids with a lower volume of local anesthetic can be added when used for treatment of chronic pain syndromes.

Sciatic Nerve Block under Ultrasound Guidance

In a study performed by Perlas and colleagues, ultrasound guidance improved the success of sciatic nerve block at the popliteal fossa.10 This study showed the success rate for ultrasound-guided block was 89.2% versus a nerve stimulator-guided group with the success rate of 60.6%. Ideally, a lower frequency ultrasound probe between 2 and 5 MHz may be used for scanning and identifying deep structures such as the sciatic nerve.

Ultrasound-Guided Popliteal Sciatic Nerve Block

Surface anatomic landmarks for sciatic nerve block at the popliteal fossa follow:

The patient is positioned prone and the surface landmarks as described earlier are identified and clearly marked. The ultrasound probe is positioned 5 to 10 cm proximal to the popliteal crease to obtain a short axis or transverse view of the sciatic nerve.11 The sciatic nerve at this level will appear as a single circular or oval structure (Fig. 26-5). The popliteal artery appears as a hypoechoic pulsatile structure medial to the sciatic nerve. Attempt to visualize the sciatic nerve in the upper portion of the popliteal fossa prior to its division into the tibial and common peroneal nerves. The ultrasound probe should be moved cephalad until this point is located. Every effort should be made to visualize the sciatic nerve in the center of the sonogram.

Sciatic Nerve Block with Fluoroscopic Guidance

Using a slight modification of the posterior approach described earlier, the sciatic nerve can be blocked at the sciatic notch using fluoroscopic guidance. Using a 25- or 22-gauge 3.5 inch spinal needle, the sciatic notch can be targeted to access the sciatic nerve. As the needle is advanced parallel to the fluoroscopic x-ray beam, and the needle comes in contact with the sciatic nerve, a paresthesia will be elicited, or the procedure can be done with a nerve stimulator as described previously. As soon as the nerve is in proximity, 1 to 2 mL of nonionic contrast media is injected and an outline of the sciatic nerve is seen (Fig. 26-6). Local anesthetic with or without 40 to 80 mg triamcinolone or other corticosteroid can be injected after negative aspiration for blood.

Complications of Sciatic Nerve Block

Various studies analyzed complications following peripheral nerve blocks.13,14 Recent studies have also examined complications after continuous popliteal sciatic nerve blocks for postoperative analgesia.15,16

Other complications of the sciatic nerve block include a transient unintended pudendal nerve block, perforation of pelvic organs, and pressure necrosis of the heel.19,20

1. Williams A. Pelvic girdle gluteal region and hip joint area. In: Standring S., editor. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice 39th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2004.

2. Mansour N.Y. Reevaluating the sciatic nerve block: Another landmark for consideration. Reg Anesth. 1993;18:322-333.

3. di Benedetto P., Bertini L., Casati A., et al. A new posterior approach to the sciatic nerve block: A prospective, randomized comparison with the classic posterior approach. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:1040-1044.

4. Singelyn F.J., Aye F., Gouverneur J.M. Continuous popliteal sciatic nerve block: An original technique to provide postoperative analgesia after foot surgery. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:383-386.

5. Ilfeld B.M., Morey T.E., Wang R.D., Enneking F.K. Continuous popliteal sciatic nerve block for postoperative pain control at home: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:959-965.

6. White P.F., Issioui T., Skrivanek G.D., et al. The use of a continuous popliteal sciatic nerve block after surgery involving the foot and ankle: Does it improve the quality of recovery? Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1303-1309.

7. Mansour N.Y. Reevaluating the sciatic nerve block: Another landmark for consideration. Reg Anesth. 1993;18:322-323.

8. Morris G.F., Lang S.A., Dust W.N., Van der Wal M. The parasacral sciatic nerve block. Reg Anesth. 1997;22:223-228.

9. Vloka J.D., Hadzić A., April E., Thys D.M. The division of the sciatic nerve in the popliteal fossa: Anatomical implications for popliteal nerve blockade. Anesth Analg. 2001;92(1):215-217.

10. Perlas A., Brull R., Chan V.W., et al. Ultrasound guidance improves the success of sciatic nerve block at the popliteal fossa. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33(3):259-265.

11. Sinha A., Chan V.W. Ultrasound imaging for popliteal sciatic nerve block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29(2):130-134.

12. Barrington M.J., Lai S.L., Briggs C.A., et al. Ultrasound-guided midthigh sciatic nerve block—a clinical and anatomical study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33(4):369-376.

13. Capdevila X., Pirat P., Bringuier S., et al. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in hospital wards after orthopedic surgery: A multicenter prospective analysis of the quality of postoperative analgesia and complications in 1,416 patients. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1035-1045.

14. Auroy Y., Benhamou D., Bargues L., et al. Major complications of regional anesthesia in France: The SOS regional anesthesia hotline service. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1274-1280.

15. Compère V., Rey N., Baert O., et al. Major complications after 400 continuous popliteal sciatic nerve blocks for post-operative analgesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:339-345.

16. Borgeat A., Blumenthal S., Lambert M., et al. The feasibility and complications of the continuous popliteal nerve block: A 1001-case survey. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:229-233.

17. Neuburger M., Buttner J., Blumenthal S., et al. Inflammation and infection complications of 2285 perineural catheters: A prospective study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51:108-114.

18. O’Grady N.P., Alexander M., Dellinger E.P., et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23:759-769.

19. Vloka J.D., Hadzić A. Block of the Sciatic Nerve in the Popliteal Fossa. In: Hadzić A., editor. The New York School of Regional Anesthesia Textbook of Regional Anesthesia and Acute Pain Management. New York: McGraw Hill; 2007:532-553.

20. Gaertner G., Fouche E., Chouquet, et al. Sciatic nerve block. In: Hadzić A., editor. The New York School of Regional Anesthesia Textbook of Regional Anesthesia and Acute Pain Management. New York: McGraw Hill; 2007:517-531.