Tracheal tubes

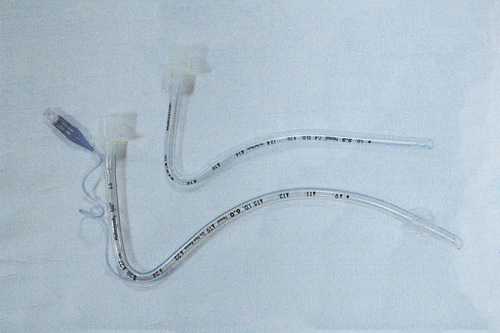

Contemporary tracheal tubes have circular walls, which help prevent kinking. The proximal portion (the machine end) attaches through a standardized connector to the anesthetic circuit. The distal portion (the patient end) typically includes a slanted portion, called the bevel, and a Murphy eye (Figure 10-1), which provides an alternative conduit for gas flow should the tip of the tube obstruct if pressed against the carina or wall of the trachea. Tracheal tubes also commonly have a radiopaque marker that runs the length of the tube and can be used radiographically to determine tube position within the trachea.

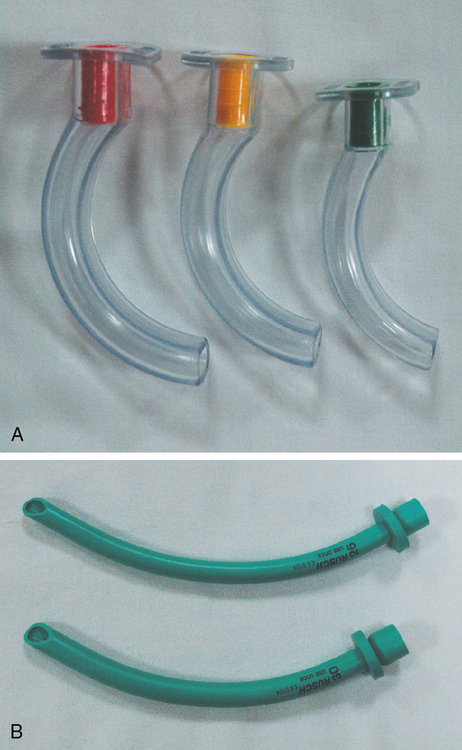

Most adults are intubated with cuffed tubes, whereas the practice of using cuffed versus uncuffed tubes varies in children (Figure 10-2). The cuff acts as a seal between the tube and the trachea, the purpose of which is threefold: to prevent aspiration of pharyngeal, gastric, or foreign objects into the trachea; to prevent gas leak; and to center the tube in the trachea. If the tracheal tube includes a cuff, it will also have an inflation valve, a pilot balloon, and an inflation tube at the proximal end. Several different cuff systems are in use (Table 10-1).

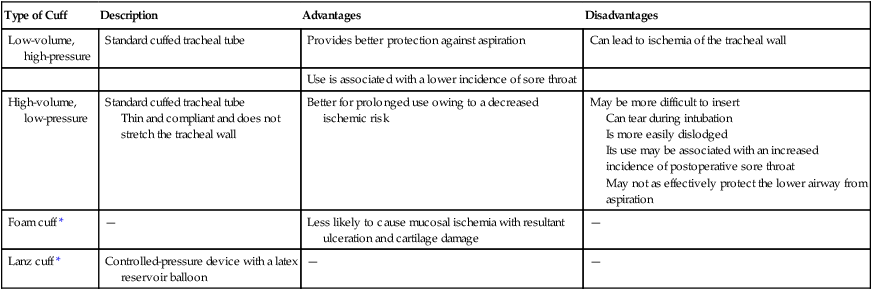

Table 10-1

Characteristics of Various Types of Airway Cuffs

| Type of Cuff | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Low-volume, high-pressure | Standard cuffed tracheal tube | Provides better protection against aspiration | Can lead to ischemia of the tracheal wall |

| Use is associated with a lower incidence of sore throat | |||

| High-volume, low-pressure | Standard cuffed tracheal tube Thin and compliant and does not stretch the tracheal wall |

Better for prolonged use owing to a decreased ischemic risk | May be more difficult to insert Can tear during intubation Is more easily dislodged Its use may be associated with an increased incidence of postoperative sore throat May not as effectively protect the lower airway from aspiration |

| Foam cuff * | — | Less likely to cause mucosal ischemia with resultant ulceration and cartilage damage | — |

| Lanz cuff * | Controlled-pressure device with a latex reservoir balloon | — | — |

*Alternative systems that do not require cuff pressure measurements.

Because a variety of factors may lead to changes in cuff pressure, some authorities recommend that cuff pressures be measured at end expiration in operations that last longer than 4 to 6 hours (Box 10-1). Pressure measurements can be obtained by connecting the inflation tube to a manometer or to the pressure channel of a monitor by using an air-filled transducer. Using the “feel” of the pilot balloon as a measurement of intracuff pressure has not been shown to be reliable. Pressures should be maintained between 25 and 34 cm H2O (18-25 mm Hg) in normotensive adults. N2O can diffuse into the cuff, leading to increased intracuff volume and pressure if the cuff is filled with air. When N2O use is discontinued, the intracuff pressure decreases rapidly; therefore, if the tracheal tube is to be left in postoperatively, the cuff should be deflated and reinflated with air to prevent a leak.

Tracheal tubes have many desirable features, such as providing a secure protected airway; decreasing pollution in the operating room by inhibiting escape of anesthetic gases; and allowing for accurate monitoring of end-tidal gases, tidal volume, and pulmonary compliance. However, their use is associated with a variety of complications (Box 10-2). Trauma from multiple attempts to intubate the trachea, excessive force, or a stylet through the Murphy eye can cause hematomas, lacerations, vocal cord avulsions and fractures, and even tracheal perforations. Obstruction from kinking, external compression, displacement, change in the patient’s body position, material in the lumen, or the patient biting the tube can occur.

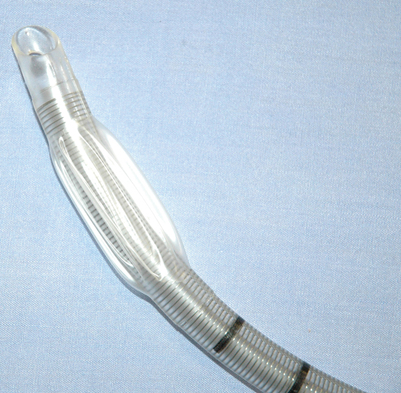

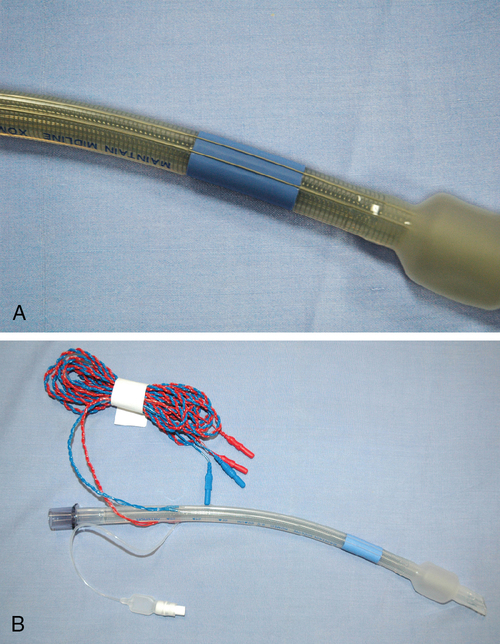

A variety of tracheal tubes are marketed. Typically, tracheal tubes are made of polyvinylchloride or silicone or, less commonly, red rubber. They can be cuffed, uncuffed, nasal, oral, reinforced (wire, see Figure 10-1), preformed (see Figure 10-2), laser-resistant (Figure 10-3), flexed (to aid with difficult intubations), reusable, disposable, and single-lumen or multilumen. Tracheal tubes with electrodes imbedded in their outer wall are being marketed for intraoperative monitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerves during thyroid or parathyroid operations (Figure 10-4).

Reinforced tubes, also known as wire spirals, usually have a metal-wound or nylon-wound spiral reinforcing wire incorporated into the wall of the lumen, which makes them relatively resistant to bending, compression, and kinking and, therefore, well suited for use in tracheal operations (see Figure 10-1). However, these tubes may be difficult to pass nasally without a stylet or orally through an intubating laryngeal mask airway (LMA). Perhaps most disadvantageous is that a patient may bite through the tube.

Preformed tubes, also known as Ring-Adair-Elwin (RAE) tubes, are useful during oral surgery and for head and neck operations (see Figure 10-2). They have a preformed bend that directs the tube away from the surgical field. An oral RAE tube rests on the patient’s chin and is directed toward the chest. A nasal RAE is longer and directs the proximal end of the tube toward the patient’s forehead.

Laser-resistant tubes (see Figure 10-3) were designed to be nonflammable for use during operations in which a laser is used; however, airway fires may still occur if the laser power is great enough or if the duration of application of the laser is too long. Different laser-resistant tubes vary in their compatibility with various laser types; compatibility should always be checked prior to use. The most common lasers are CO2, potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP), neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG), and argon. Cuffs are not laser resistant and, therefore, should be filled with water or saline. Some tubes have two cuffs so that if one cuff is damaged, the other can be inflated to provide a seal and prevent a leak.

Multilumen tubes are used for gas sampling, suctioning, airway pressure monitoring, fluid and drug injection, jet ventilation, and lung isolation. The double-lumen tube (DLT) is commonly used for lung isolation and can be right- or left-sided (Figure 10-5). The tracheal lumen is placed above the carina, and the bronchial lumen is angled to fit into either the right or left mainstem bronchus. DLTs are sized according to the external diameter of the tracheal segment. The margin of safety is greater for a left-sided tube, and therefore, it is often the tube of choice even for left-lung operations. A right-sided DLT is necessary in specific circumstances (Box 10-3). The tracheal cuff should be inflated in the same manner in which a regular tracheal tube is inflated. The bronchial cuff should be inflated incrementally until a seal is achieved. Volumes in the bronchial cuff should be less than 3 mL. Complications associated with the use of the DLT include difficulty with insertion and positioning, hypoxemia, obstructed ventilation, trauma, poor seal, and cuff rupture.

Supraglottic airways

The most commonly used supraglottic airway, the LMA, is less invasive than a tracheal tube and creates a hands-free seal. The LMA is a curved tube (shaft) that is connected to an elliptical spoon-shaped mask (cup). The two flexible bars where the tube attaches to the mask prevent obstruction by the epiglottis (Figure 10-6). The LMA also comes with an inflatable cuff, inflation tube, and self-sealing pilot balloon. When placed correctly, the mask should rest on the hypopharyngeal floor, the sides should face the piriform fossae, and the upper portion of the cuff should sit behind the tongue base. Although weight-based formulas can be used for sizing, a man or larger adult will typically require a size 5, and a woman or smaller adult, a size 4. For pediatric sizing, matching the widest part of the mask to the width of the second to fourth fingers works well.

The LMA can be useful for a patient in whom mask ventilation is difficult; the use of an LMA is included in the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ algorithm to facilitate tracheal intubation for management of the patient with a difficult airway. LMAs are typically easy to insert and use, are cost effective, and provide for a smooth awakening. However, they do not protect against aspiration, can lead to gastric distention, can cause airway trauma, and have relative contraindications to their use; therefore, their use is contraindicated in specific situations (Box 10-4).

Facemasks

Facemasks can be made of black rubber, clear plastic, elastomeric material, or a combination thereof. They include a body, seal, and connector (Figure 10-7) and can be used to ventilate with positive pressure and to administer inhaled anesthetic gases. Advantages include a decreased incidence of postoperative sore throat, cost effectiveness, and decreased anesthetic requirement. Facemask anesthesia, however, is demanding of the anesthesia provider, requires higher fresh-gas flows, leads to increased pollution in the operating room, causes more O2 desaturation, increases the work of breathing, and can cause pressure necrosis, dermatitis, nerve injury, jaw pain, and increased movement of the cervical spine.

Pharyngeal airways

Pharyngeal airways are typically made of plastic or elastomeric material (Figure 10-8) and help prevent obstruction of the laryngeal space by the tongue or epiglottis without the anesthesia provider having to manipulate the patient’s cervical spine. They can also reduce the work of breathing, as compared with a facemask. Oropharyngeal airways (Figure 10-8, A) are made up of a flange, bite portion, and air channel and are useful for maintaining an open airway, preventing biting, facilitating suctioning, and providing a pathway for inserting devices, such as a fiberscope or endoscope, into the pharynx. Oropharyngeal airways can stimulate pharyngeal and laryngeal reflexes, leading to coughing or laryngospasm. Nasopharyngeal airways (Figure 10-8, B) are better tolerated in a patient with intact airway reflexes and can be used for many of the same purposes as the oral airway. In addition, they can be used to administer continuous positive airway pressure, treat hiccoughs, and dilate the nasal passages for nasotracheal intubation. The use of a nasopharyngeal airway should be avoided when the patient is anticoagulated or has a basilar skull fracture, nasal deformity, nasal infection, or history of nosebleeds requiring treatment. A vasoconstrictor can be applied topically to the patient’s nasopharynx before the airway is inserted to decrease the risk of bleeding and to facilitate passage—vasoconstriction decreases mucosal thickness, enlarging the nasal passageway.