Tobacco use in surgical patients

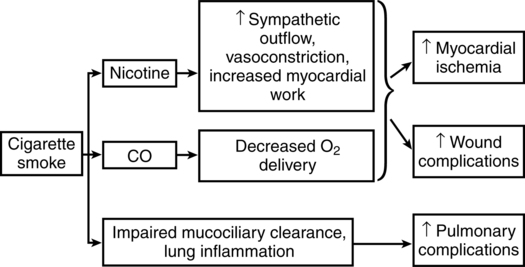

Approximately 20% of adults in the United States smoke cigarettes, and each year an estimated 10 million smokers undergo surgical procedures. Chronic and acute exposures to cigarette smoke cause profound changes in physiology that increase the perioperative risk of cardiovascular, pulmonary, and wound-related complications occurring (Figure 107-1). Thus, the knowledge of how smoking and abstinence from cigarettes affect perioperative physiology is of practical importance. This chapter will review (1) why smokers should maintain perioperative abstinence from smoking for as long as possible, (2) why surgery provides a good opportunity to quit smoking permanently, and (3) how anesthesiologists can help their patients quit smoking.

Helping patients quit smoking

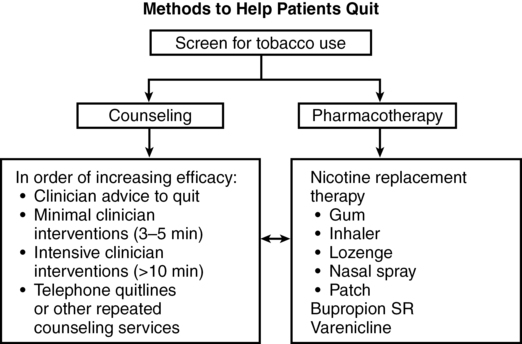

Treatment of tobacco dependence involves both behavioral counseling (to address the habit of smoking) and pharmacotherapy (to address nicotine addiction) (Figure 107-2). Even brief advice to stop smoking offered by physicians increases quit rates. More intensive counseling further increases quit rates. It may not be practical for anesthesiologists to deliver intensive behavioral interventions, as most are not trained to do so and time is limited in busy clinical practices; however, anesthesiologists can refer patients to other existing services, such as telephone quitlines, which are available in all states (1-800-QUIT-NOW) and can provide assistance and follow-up at low or no cost to smokers attempting to quit. Pharmacotherapy helps smokers treat symptoms of nicotine withdrawal, including cravings for cigarettes. Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) in the forms of gum, inhaler, patch, and lozenges is effective in promoting abstinence, with many forms available without prescription. NRT does not produce adverse cardiac effects in healthy smokers and is safe in patients with cardiovascular diseases. There is no evidence that therapeutic doses of NRT in humans affect wound healing; therefore, current evidence supports the safety of NRT for surgical patients. Good success in maintaining abstinence has been reported with a combination of pharmacotherapy (bupropion SR or varenicline tartrate) and psychotherapy (e.g., individual, group, or telephone-based therapy).