Chapter 60 The pancreas as a site of metastatic cancer

Overview

Resection has become an established part of the standard therapy for liver and lung metastases of several primary tumors (Fong et al, 1999; Quiros & Scott, 2008). Unlike liver and lung, the pancreas is an uncommon site of metastases. In autopsy series, 3% to 12% of patients with diffuse metastatic disease have pancreatic involvement (Showalter et al, 2008), and metastases account for only about 2% to 4% of malignant lesions in the pancreas (Showalter et al, 2008; Strobel et al, 2009). However, this number is increased up to 40% in patients with a pancreatic mass and a history of malignant disease (Roland & van Heerden, 1989; Z’Graggen et al, 1998).

Metastases to the pancreas may occur as isolated lesions or with additional extrapancreatic metastases that are technically resectable; isolated pancreatic metastases are very rare. Until recently the available data on resection for pancreatic metastases were based only on small series and multiple case reports. However, recent larger series and meta-analyses suggest that resection for pancreatic metastases is safe and associated with a favorable long-term outcome in appropriate patients (Reddy et al, 2008; Reddy & Wolfgang, 2009; Strobel et al, 2009; Tanis et al, 2009). This is best documented for metastastic renal cell carcinoma (RCC), the most frequent primary tumor of isolated pancreatic metastases (Sellner et al, 2006; Tanis et al, 2009). Based on these recent data, pancreatic resection can be recommended as part of an interdisciplinary treatment in metastatic disease to the pancreas.

Results of Surgery for Pancreatic Metastases

Because isolated pancreatic metastases and metastases with localized, treatable extrapancreatic disease are uncommon, the results of pancreatic resection for metastases are not as well documented as for the liver or lung (Fong et al, 1999; Internullo et al, 2008). Until recently, the available literature was based only on smaller series and multiple case reports, which inherently tend to be biased toward the report of favorable results. However, in recent years, resection for metastases to the pancreas has been used more frequently, resulting in several larger series and, most recently, meta-analyses. This change occurred for several reasons. In the last decades, morbidity and mortality rates of pancreatic surgery decreased considerably, and pancreatic surgery can now be considered a safe procedure when performed by experienced surgeons (see Chapter 62A, Chapter 62B ). With the development of more effective drugs and tailored chemotherapy, the prognosis of metastatic disease has largely improved for several tumor entities. Also, with standardized follow-up programs after resection for cancer and with broader use of cross-sectional imaging, pancreatic metastases are more frequently detected at a resectable stage. Finally, the decision for resection of a pancreatic metastasis is more frequently made in an interdisciplinary setting, such as by tumor boards, which are established in most centers.

Safety of Resection for Pancreatic Metastases

In a recent review of 19 series, a mortality rate of 1.2% and a morbidity rate of 38.3% were reported for resection of isolated pancreatic metastases (Reddy & Wolfgang, 2009). Resections for metastatic disease may be more difficult than resections for primary pancreatic tumors because of the necessity of extensive adhesiolysis after previous surgery in approximately 80% of patients and because of the necessity of multivisceral resections. Our series, which included 41% multivisceral resections, reported a mortality rate of 4.4% and a morbidity rate of 33% (Strobel et al, 2009). These findings are comparable to the data reported for primary pancreatic malignancies and show that resection for pancreatic metastases can be performed safely by specialized surgeons.

Oncologic Outcome of Resection for Pancreatic Metastases

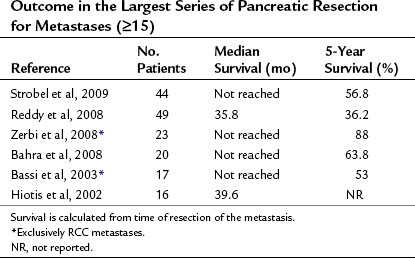

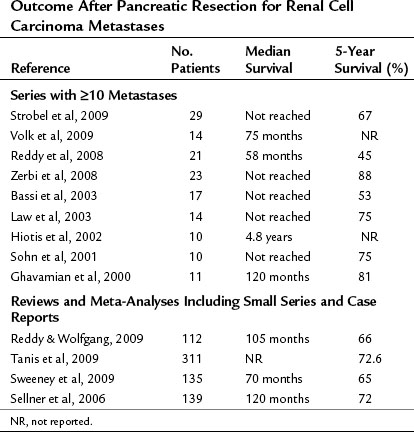

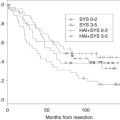

The follow-up results of the largest studies of resection for pancreatic metastases are summarized in Table 60.1 and show a very favorable outcome. However, most series include several primary tumor entities, and conclusions about individual tumor types must be made with great caution. RCC is, by far, the most frequent primary tumor associated with resectable, isolated pancreatic metastases. The frequency of various primary tumors derived from surgical series is given in Table 60.2. The data for resection of RCC metastatic to the pancreas are summarized in Table 60.3; they show considerably longer survival rates compared with the mixed group of other histologies (see Table 60.1). Two systematic reviews of 236 and 311 published cases of surgery for RCC pancreatic metastases (Sellner et al, 2006; Tanis et al, 2009) report 5-year survival rates of about 75% after radical resection. However, because both reviews included case reports and smaller series, they may overestimate survival rates because of publication bias. However, RCC histology was also associated with improved outcome in several of the published series, including that of the authors (Eidt et al, 2007; Hiotis et al, 2002; Reddy et al, 2008; Strobel et al, 2009).

Table 60.2 Pathologic Diagnosis in Patients with Pancreatic Resections for Metastases

| Primary Tumor Type | No. Patients | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Renal cell cancer | 181 | 63.1 |

| Colorectal cancer | 22 | 7.7 |

| Sarcoma | 17 | 5.9 |

| Melanoma | 13 | 4.5 |

| Gastric cancer | 10 | 3.5 |

| Lung cancer | 9 | 3.1 |

| Gallbladder cancer | 8 | 2.9 |

| Breast cancer | 6 | 2.1 |

| Ovarian cancer | 5 | 1.7 |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | 2 | 0.7 |

| Esophageal cancer | 2 | 0.7 |

| Mesenteric fibromatosis | 2 | 0.7 |

| Schwannoma | 2 | 0.7 |

| Merkel cell carcinoma | 1 | 0.3 |

| Seminoma | 1 | 0.3 |

| Teratocarcinoma | 1 | 0.3 |

| Hemangiopericytoma | 1 | 0.3 |

| Urinary bladder cancer | 1 | 0.3 |

| Carcinoid | 1 | 0.3 |

| Nonpancreatic endocrine tumor | 1 | 0.3 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 | 0.3 |

Based on combined data from Reddy & Wolfgang, 2009, and Strobel et al, 2009.

Although 57% of cases in our series had extrapancreatic metastatic disease, the overall 5-year survival rate was 56.8%, and the 5-year survival rate was 67.3% after resection of RCC metastases. The 5-year survival rate after resection of isolated pancreatic metastases was as high as 75% (Strobel et al, 2009).

Efficacy of Resection for Pancreatic Metastases

Although comparison of the survival data after metastasectomy with the historic results of conservative treatment suggests a benefit of surgery, the efficacy of surgical resection and its superiority over conservative treatment alone cannot be formally proven because of the lack of controlled trials. However, for RCC, three studies observed longer survival in patients after resection compared with noncontrolled groups with irresectable disease (Sellner et al, 2006; Tanis et al, 2009; Zerbi et al, 2008). Furthermore, the survival data after pancreatic resection for RCC metastases compare very favorably to the survival reported for resection of RCC metastases in other organs (Kavolius et al, 1998). Another point supporting resection for pancreatic metastases is good local tumor control. In our series, local tumor control after 5 years was 87%, but disease-free survival was only 33% because of distant metastases (Strobel et al, 2009). This underlines the importance of interdisciplinary therapy with consideration of adjuvant treatment in these patients.

Surgical Approach in Patients with Pancreatic Metastases

Presentation of Patients with Pancreatic Metastases

Patients with pancreatic metastases can be divided into two groups: those with symptoms and those without. Patients in the first group experience typical symptoms caused by a pancreatic tumor, and the diagnostic workup reveals a pancreatic mass that often has features atypical for primary pancreatic cancer (Palmowski et al, 2008). In the second group of patients, the lesion is found during standardized follow-up exams for the primary tumor or by imaging for other reasons. Within the past few decades, the distribution has shifted from symptomatic to asymptomatic patients, most likely as a result of standardized follow-up programs and broad use of cross-sectional imaging techniques. In studies that include patients from previous decades, 60% to 90% of patients were seen because of symptoms (Reddy et al, 2008; Sellner et al, 2006; Tanis et al, 2009); in the authors’ recent series, only 18% of metastases were diagnosed because of symptoms, and 82% were detected during oncologic follow-up (Strobel et al, 2009). Patients with symptoms appear to have a worse prognosis, as has been shown for RCC metastases (Tanis et al, 2009). These findings suggest that symptoms eventually develop as local complications during progression of pancreatic metastases and present another point in favor of surgery for resectable metastatic disease.

Interestingly, pancreatic metastases frequently are identified long after resection of the primary tumor. This is best documented for RCC metastases, which are diagnosed at a median interval of 10 years after resection of the primary tumor (Sellner et al, 2006; Strobel et al, 2009). This long disease interval must be taken in account in the design of oncologic follow-up programs.

Diagnostic Workup for Suspected Pancreatic Metastases

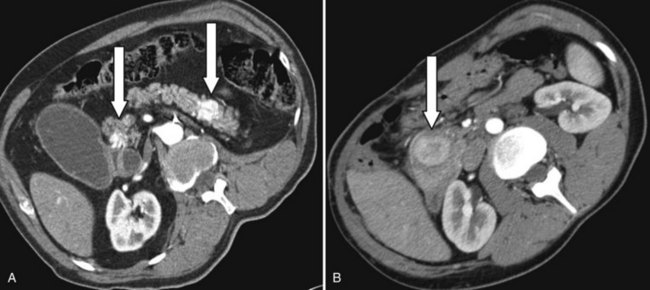

Usually, a pancreatic mass is first detected by contrast-enhanced computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. Pancreatic metastases have features different from primary pancreatic malignancies (see Chapters 16 and 17). In contrast to pancreatic adenocarcinoma, most metastatic entities exhibit contrast enhancement, as shown in Figure 60.1 (Palmowski et al, 2008), particularly mestastatic RCC. Another feature of metastases is their multifocality within the pancreas: 40% in pathologic workup in our series. Perhaps because of the long interval between the primary tumor resection and the pancreatic metastases, these lesions are often misdiagnosed as primary pancreatic malignancy.

Patient Selection for Surgery

Primary Tumor Type

Clearly, the biology of the primary tumor is a key factor influencing the outcome. Patients with RCC metastases have a significantly better outcome than patients with other malignancies (Strobel et al, 2009), likely the result of a relatively slow tumor biology and, more recently, of more effective chemotherapy. Although the expected outcome in other malignancies, such as melanoma, is much worse, the decision for surgery can be based on the lack of effective nonoperative treatment in some tumor entities. Thus the decision for pancreatectomy for metastatic disease, as from other metastatic sites, can only be based on the experience with metastasectomy, per se, in each specific tumor entity.

History of the Disease

In our recent series, a prolonged interval (>36 months) between the primary tumor and the occurrence of the pancreatic metastasis was associated with improved survival. Of importance, a previous recurrence only affected disease-free but not overall survival (Strobel et al, 2009).

Pattern of Recurrent Disease

As expected, the presence of extrapancreatic disease is associated with shorter disease-free and overall survival (Strobel et al, 2009). This further highlights the importance of a thorough diagnostic workup to rule out local or extrapancreatic systemic recurrence of the primary tumor, as previously discussed. However, the survival results show that additional extrapancreatic disease should not necessarily preclude a patient from resection if the pattern is not multifocal/diffuse and if a complete resection can be expected.

Local Resectability, Patient Comorbidities, and Operative Risk

Given the lack of studies to evaluate factors that determine local resectability of pancreatic metastases, the same parameters used for primary pancreatic malignancies can be applied and typically involve assessment of mesenteric vascular and/or adjacent organ involvement (see Chapter 62A).

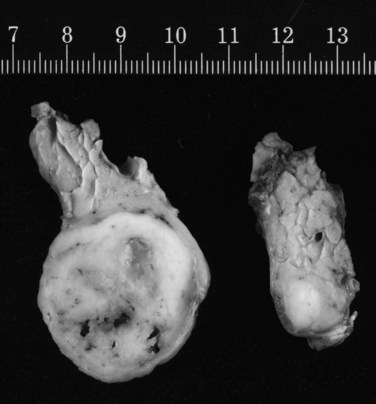

Technique of Resection for Pancreatic Metastases (See Chapter 62A)

No studies have compared different techniques of pancreatic resection, and most larger studies only describe radical resections. However, in one report, a high rate of pancreatic recurrence was observed after limited resections (Bassi et al, 2003). In our series, we performed standard partial resections but avoided total pancreatectomy whenever possible and observed only two pancreatic recurrences after 30 partial (6.7%) pancreatectomies (Strobel et al, 2009). Because pancreatic metastases are frequently multifocal (Fig. 60.2), a thorough exploration of the pancreatic remnant by palpation and ultrasound is mandatory whenever a partial pancreatectomy is performed (Zerbi et al, 2008). Because the two largest series showed that pancreatic metastases are associated with peripancreatic lymph node metastases in 26% to 30% of patients (Reddy et al, 2008; Strobel et al, 2009), a standard peripancreatic lymphadenectomy should be performed during pancreatic resection for metastases. To achieve curative resection, multivisceral resections should be performed if the operative risk and potential benefit are acceptable.

Bahra M, et al. Metastatic lesions to the pancreas: when is resection reasonable? Chirurg. 2008;79:241-248.

Bassi C, et al. High recurrence rate after atypical resection for pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2003;90:555-559.

Eidt S, et al. Metastasis to the pancreas: an indication for pancreatic resection? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2007;392:539-542.

Fong Y, et al. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309-318.

Ghavamian R, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the pancreas: clinical and radiological features. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:581-585.

Hiotis SP, et al. Results after pancreatic resection for metastatic lesions. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:675-679.

Internullo E, et al. Pulmonary metastasectomy: a survey of current practice amongst members of the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:1257-1266.

Kavolius JP, et al. Resection of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2261-2266.

Law CH, et al. Pancreatic resection for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: presentation, treatment, and outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:922-926.

Palmowski M, et al. Metastasis to the pancreas: characterization by morphology and contrast enhancement features on CT and MRI. Pancreatology. 2008;8:199-203.

Quiros RM, Scott WJ. Surgical treatment of metastatic disease to the lung. Semin Oncol. 2008;35:134-146.

Reddy S, et al. Pancreatic resection of isolated metastases from nonpancreatic primary cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3199-3206.

Reddy S, Wolfgang CL. The role of surgery in the management of isolated metastases to the pancreas. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:287-293.

Roland CF, van Heerden JA. Nonpancreatic primary tumors with metastasis to the pancreas. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;168:345-347.

Sellner F, et al. Solitary and multiple isolated metastases of clear cell renal carcinoma to the pancreas: an indication for pancreatic surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:75-85.

Showalter SL, Hager E, Yeo CJ. Metastatic disease to the pancreas and spleen. Semin Oncol. 2008;35:160-171.

Sohn TA, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the pancreas: results of surgical management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:346-351.

Strobel O, et al. Survival data justifies resection for pancreatic metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;6(12):3340-3349. Epub Sep 24 2009

Sweeney AD, et al. Value of pancreatic resection for cancer metastatic to the pancreas. J Surg Res. 2009;156(2):189-198. Epub Feb 10 2009

Tanis PJ, et al. Systematic review of pancreatic surgery for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2009;96:579-592.

Volk A, et al. Surgical therapy of intrapancreatic metastasis from renal cell carcinoma. Pancreatology. 2009;9:392-397.

Z’Graggen K, et al. Metastases to the pancreas and their surgical extirpation. Arch Surg. 1998;133:413-417.

Zerbi A, et al. Pancreatic metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: which patients benefit from surgical resection? Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1161-1168.