12 Tendon Sheath and Insertion Injections

Tendons are impressively strong structures that link muscles to bone. They function to transmit the force of muscular contraction to a bone, thereby moving a joint or helping to immobilize a body part. Their microscopic organization is thoroughly described elsewhere.1–3

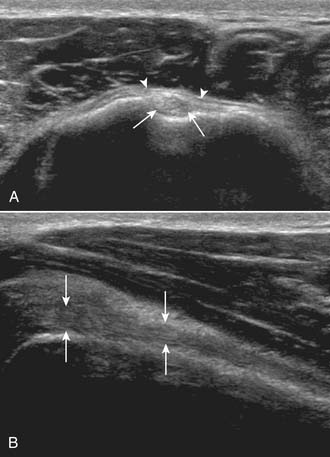

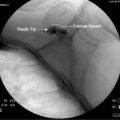

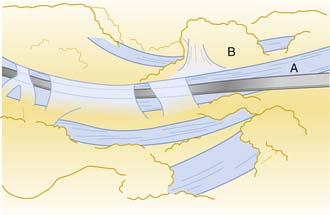

The organizational unit in a tendon is the collagen fibril, which collectively forms fascicles, which as a group compose the tendon itself.4 Some tendons, especially long ones, are guided and lubricated along their paths by sheaths (Fig. 12-1) (e.g., biceps brachii, (Fig. 12-2) extensor pollicis brevis, and abductor pollicis longus).

Figure 12-1 Drawing demonstrating a flexor tendon (A) within its sheath. The paratendinous septum is reflected (B).

A prototypical muscle consists of the muscle belly centrally, two musculotendinous junctions, and tendinous insertions into bone at the points of anatomic origin and insertion.5 Some muscles, such as the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis at the elbow, attach directly into bone (Figs. 12-3), an arrangement that may be more susceptible to injury.6

Much is known about a tendon’s response to laceration and operative repair,2 although this clinical situation is not frequently encountered. Less is understood about the more common and clinically relevant overuse tendinitis. A tendon and its sheath (if present) will undergo a typical inflammatory response to acute or chronic overuse injury, followed by a regenerative repair process.2,7,8 The distinction between an overload type of acute injury and a chronic overuse mechanism will aid in successful rehabilitation of tendinitis.9

Corticosteroid Injections

Cortisone and its derivatives are known to reduce or prevent inflammation. Numerous corticosteroid preparations are available for local injection10 (see Chapter 2 on medications). The injectable corticosteroids are suspensions of insoluble particles, and therefore, the antiinflammatory effect is profound only where the material is deposited.11 The ability of corticosteroids to control inflammation makes them a valuable adjunct in treating tendon injuries because they do not alter the underlying process that leads to inflammation.10

Efficacy

McWhorter and colleagues injected hydrocortisone acetate into rat Achilles peritenons that had been previously injured.3 There were no deleterious effects of one, three, or even five injections, measured biomechanically (tension to failure) or histologically (light microscopy), compared to controls. This finding should reassure physicians that they are not doing harm with properly placed steroid injections. A 30-year literature review identified eight prospective, placebo-controlled studies of steroid injection treatment for sports-related tendinitis.12 Three of the studies showed beneficial effects of injections at clinical follow-up. A meta-analysis of properly designed investigations of steroid injection for Achilles tendinitis found no beneficial effects,13 although very few studies qualified as rigorous. Adverse side effects occurred with a 1% incidence. No “proof” of the usefulness or uselessness of this treatment modality exists.

Contraindications, Complications, and Side Effects

The lack of a specific diagnosis is the single largest contraindication to a local corticosteroid injection. If the diagnosis is clear and the antiinflammatory effect of a corticosteroid may facilitate the rehabilitation process, injection can be considered.10

Repeated injections to the same area must be avoided, particularly into joints. Alterations in articular cartilage have been documented with repeated administration,14 possibly resulting in joint damage and weakened ligaments.15 A widely recognized complication of steroid injection is tendon rupture, a negative outcome that appears to be decreasing in frequency because it is now well understood. Achilles and other tendon ruptures have been reported,16–26 and deposition of injected material directly into any tendon substance is contraindicated. One report links the effect of repeated steroid injections to rupture of the plantar fascia.27

Some experimental findings have suggested that corticosteroid administration led to smaller, weaker tendons as a side effect.28 A more common side effect is subcutaneous atrophy, especially at the knee and lateral elbow and more frequently with the use of triamcinolone.10 Theoretically, atrophy of the specialized fat pads of the heel following steroid injection for plantar fasciitis may lead to a significant disability in an athlete, due to the loss of cushioning effect.

Alternatives to Corticosteroids

Percutaneous tenotomies have been described for treatment of chronic lateral epicondylitis and plantar fasciitis.18,29 These injections are performed with large bore needles (18 or 20 gauge) under ultrasound guidance. The needle tip is used to repeatedly fenestrate the affected tissue under local anesthetic. The bony surface (i.e., epicondyle) can be abraded and calcifications may be fragmented. This technique is thought to be a safe and effective alternative to corticosteroid injections.18,29

Platelet rich plasma injections use concentrated platelets from autologous blood to stimulate a healing response in damaged tissue. Blood is drawn from the patient and placed in a centrifuge. The concentrated platelets are removed and reinjected directly into the patient’s abnormal musculotendinous tissue or ligament usually under ultrasound guidance. These concentrated platelets produce growth factors that include platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). These compounds are instrumental in attracting cells that promote healing by stimulating neovascularization and cellular reproduction.4,5,7,30 The efficacy of PRP injections and appropriate clinical indications (when and where it should be used) are currently being researched and yet to be definitively determined. Initial results of clinical studies appear promising.13,31,32

Methods of Injection

Tendon and tendon sheath injections are office procedures, typically performed under clean or sterile conditions. The corticosteroid of choice is often combined with a local anesthetic, the latter helping to confirm the proper location of the deposited material. Diagnostic ultrasound has been advocated to guide injections near the heel when guidance by palpation alone fails.33

Indications

Diagnosis

Corticosteroid or local anesthetic injections should not be used routinely to arrive at diagnoses pertinent to the musculoskeletal system. The range of physical examination techniques used by the physician is described elsewhere34 and, in most cases, will suffice at pinpointing the specific cause of pain. The distinction between the conditions of subacromial bursitis and rotator cuff tendinitis can be clarified with injection,10 but even in this case the physical examination and subsequent rehabilitation program deservedly receive most of the attention.

Treatment

In most instances, the literature supports an adjunctive, not primary, role for injections in the treatment of tendon and tendon sheath injuries.10,20 When the doctor and patient decide to proceed with injection, the control of inflammation that is obtained should be used to facilitate the prescribed rehabilitation program, rather than being the only treatment. The area of exception to this generalization is the wrist and hand (to be discussed in detail later).

Upper Extremity Injections

The literature supports the use of corticosteroid injections as a primary treatment for stenosing flexor tenosynovitis in the hand, known as trigger thumb or trigger digit.30,35–41 In this setting, injection has been shown to be as effective as operative release of the tendon sheath and to have fewer complications.42 Injection has been employed successfully into the hands of patients with diabetes mellitus and trigger digit, but the success rate may be reduced.43,44 Instillation of the material directly into the tendon sheath has no apparent benefit over subcutaneous placement.45 Multiple pulley rupture17 and flexor digitorum profundus and superficialis tendon rupture16 has been reported as a complication from this injection. As with other soft tissue injections, a physician treating trigger finger with instillation of corticosteroid needs to maintain expertise by performing this procedure at least several times yearly.

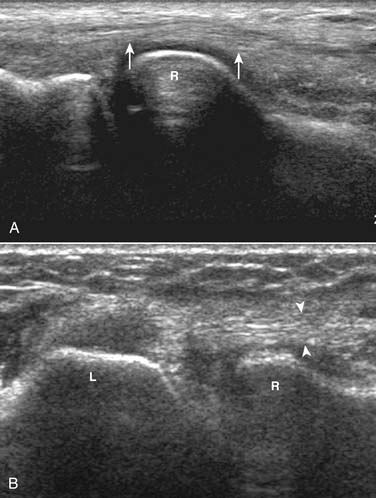

Stenosing tenosynovitis of the first dorsal wrist compartment also is known as de Quervain syndrome. This compartment typically transmits the tendons of both the abductor pollicis longus (APL) and extensor pollicis brevis (EPB). However, anatomic studies have demonstrated that multiple APL slips are common, as are two subcompartments.39 Interestingly, although one or more injections are usually successful in treating de Quervain syndrome nonoperatively,22,46 patients requiring subsequent operative release have been found to have two subcompartments in greater than expected frequency.22,46 Trigger digit and de Quervain syndrome, therefore, are usually treated successfully nonoperatively, and corticosteroid injection is the primary component of the management (Fig. 12-4).

The use of corticosteroid injection for lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow) appears widespread (Fig. 12-5), although carefully controlled studies to confirm its efficacy are absent from the literature.47 One prospective investigation found that corticosteroid injection was more effective in controlling symptoms 8 weeks after injury than anesthetic alone, but the benefit disappeared by 24 weeks.29 This may be explained by the finding that the histology of tennis elbow is noninflammatory.48 A prospective chart review found that injection alone was effective in 91% of patients within 1 week, but was associated with a 51% recurrence after 3 months. Initially, a standard physical therapy regimen led to improvement in only 74%, but the recurrence rate dropped to 5%.49 In the typical clinical setting, of course, injection(s) and physical therapy are often combined with careful consideration of the intrinsic and extrinsic biomechanical factors that may be contributors.9,50

No recent studies have examined the use of corticosteroid injections in the treatment of biceps brachii tendinitis. In this area, care should be taken to deposit the suspension to bathe the tendon sheath rather than into the body of the tendon itself (Fig. 12-6). Additionally, heavy lifting or vigorous exercise of the arm should be restricted for 48 to 72 hours following injection.

Figure 12-6 Injection technique for long head of biceps brachii. The needle is directed parallel to the tendon.

Corticosteroid injection has been found to be effective for rotator cuff tendinitis—at least for the first several weeks. In one study, injection was superior to placebo and to oral antiinflammatory medication over the course of 4 weeks.51 No more than three injections are recommended.10 The technique itself is detailed elsewhere.11 After corticosteroid injection for treatment of rotator cuff tendinitis, heavy lifting and excessive overhead work are to be avoided for at least 2 days.

Lower Extremity Injections

Although it is not a true tendinitis, plantar fasciitis is commonly treated with steroid injection(s) (Fig. 12-7). If used, they must be considered complementary to a complete rehabilitation program that includes flexibility training and correction of any contributing intrinsic or extrinsic biomechanical factors.10 If lipoatrophy occurs in the fat pad of the heel secondary to corticosteroid deposition, true disability in the active individual may result. Cosmesis is less of a problem because of the location.

Most physicians are aware of possible tendon rupture if corticosteroid is injected directly into the Achilles tendon.34,52,53 On the other hand, the Achilles sheath can be injected,11 often with a good therapeutic result. One double-blind, randomized, controlled study found no advantage of Achilles tendon sheath injections when compared with standard physical therapy measures.54

Iliotibial band tendinitis, refractory to other measures, sometimes responds to corticosteroid injection. The material is placed around the insertion of the iliotibial band at the proximal, lateral tibia, or, depending on the site of symptoms, where it passes over the prominence of the lateral femoral condyle.10 Iliopsoas tendinitis has been similarly treated,55 with up to 2 years of symptomatic relief. The quadriceps (infrapatellar) tendon can be injected for cases of tendinitis,11 but because this is a weight-bearing structure, many practitioners avoid this procedure for fear of rupture.

Conclusion

In most cases of tendinitis or tenosynovitis of the upper or lower limb, corticosteroid injection for control of inflammation should be considered as a supplement to an individualized, well-designed, rehabilitation program. Notable exceptions are trigger digit or thumb, in which corticosteroid therapy is a successful primary intervention, and, to a lesser extent, de Quervain syndrome. The physician using corticosteroid injections must perform them often enough to maintain technical expertise. Three injections for any given injured area is considered a conservative maximum. Subcutaneous atrophy is a common side effect, and the known complication of tendon rupture strongly recommends against injections of corticosteroid directly into the substance of tendons.

1. Cooper R.R., Misol S. Tendon and ligament insertion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52:1-20.

2. Kennedy J.C., Willis R.B. The effects of local steroid injections on tendons: A biomechanical and microscopic correlative study. Am J Sports Med. 1976;4:11-21.

3. McWhorter J.W., Francis R.S., Heckmann R.A. Influence of local steroid injections on traumatized tendon properties. A biomechanical and histological study. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:435-439.

4. Menetrey J., Kasemkijwattana C., Day C.S., et al. Growth factors improve muscle healing in vivo. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:131-137.

5. Yasuda K., Tomita F., Yamazaki S., et al. The effect of growth factors on biomechancical properties of the bone-patellar tendon-bone graft after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a canine model study. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:870-880.

6. Brophy D.P., Cunnane G., Fitzgerald O., Gibney R.G. Technical report: Ultrasound guidance for injection of soft tissue lesions around the heel in chronic inflammatory arthritis. Clin Radiol. 1995;50:120-122.

7. Anitua E., Andia I., Sanchez M., et al. Autologous preparations rich in growth factors promote proliferation and induce VEGF and HGF production by human tendon cells in culture. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:281-286.

8. Badalamente M.A., Sampson S.P., Dowd A. The cellular pathobiology of cumulative trauma disorders/entrapment syndromes: Trigger finger, de Quervain’s disease and carpal tunnel syndrome. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 1992;17:677.

9. Fauno P., Anderson H.J., Simonsen O. A long-term follow-up of the effect of repeated corticosteroid injections for stenosing tenovaginitis. J Hand Surg Br. 1989;14:242-243.

10. Halpern A.A., Horowitz B.G., Nagel D.A. Tendon ruptures associated with corticosteroid therapy. West J Med. 1977;127:378-382.

11. Curwin S., Stanish W.D., Tendinitis. Its Etiology and Treatment. In Lexington. Collamore Press; 1984.

12. Almekinders L.C., Temple J.D. Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of tendonitis: An analysis of the literature. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:1183-1190.

13. Mishra A., Pavelko T. Treatment of chronic elbow tendinosis with buffered platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(11):1774-1778.

14. Kerlan R.K., Glousman R.E. Injections and techniques in athletic medicine. Clin Sports Med. 1989;8:541-560.

15. Mankin H.J., Conger K.A. The acute effects of intra-articular hydrocortisone on articular cartilage in rabbits. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1966;48:1383-1388.

16. Fitzgerald B.T., Hofmeister E.P., Fan R.A., et al. Delayed flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus ruptures in a trigger finger after a steroid injection: A case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(3):479-482.

17. Gyuricza C., Umoh E., Wolfe S.W. Multiple pulley rupture following corticosteroid injection for trigger digit: A case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(8):1444-1448.

18. Housner J.A., Jacobson J.A., Misko R. Sonographically guided pecutaneous needle tenotomy for the treatment of chronic tendinosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:1187-1192.

19. Leach R., Jones R., Silva T. Rupture of the plantar fascia in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:537-539.

20. Minamikawa Y., Peimer C.A., Cox W.L., et al. De Quervain’s syndrome: Surgical and anatomical studies of the fibroosseous canal. Orthopedics. 1991;14:545-549.

21. Noyes F., Grood E., Nussbaum N. Effect of intra-articular corticosteroids on ligament properties: a biomechanical and histological study in rhesus knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1977;123:197-209.

22. Peters-Veluthamaningal C., Winters J.C., Groenier K.H., et al. Randomised controlled trial of local corticosteroid injections for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis in general practice. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009 Oct 27;10:131.

23. Reid D.C. Connective tissue healing and classification of ligament and tendon pathology. In: Reid D.C., editor. Sports Injury Assessment and Rehabilitation. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1992:65-83.

24. Sweetnam R. Corticosteroid arthropathy and tendon rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1969;51:397-398.

25. Tonkin M.A., Stern H.S. Spontaneous rupture of the flexor carpi radialis tendon. J Hand Surg Br. 1991;16:72-74.

26. Velan G.J., Hendel D. Degenerative tear of the tibialis anterior tendon after corticosteroid injection-augmentation with the extensor hallucis longus tendon, case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997;68:308-309.

27. Kapetanos G. The effect of the local corticosteroids on the healing and biomechanical properties of the partially injured tendon. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;163:170-179.

28. Geiringer S.R., Bowyer B.L., Press J.M. Sports medicine. 1. The physiatric approach. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:S428-S432.

29. McShane J.M., Nazarian L.N., Harwood M.I. Sonographically guided percutaneous needle tenotomy for treatment of common extensor tendinosis in the elbow. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:1281-1289.

30. de Mos M., van der Windt A.E., Jahr H., et al. Can platelet-rich plasma enhance tendon repair? A cell culture study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1171-1178.

31. Sanchez M., Azofra J., Anitua E., et al. Plasma rich in growth factors to treat articular cartilage avulsion: A case report. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1648-1652.

32. Sanchez M., Anitua E., Azofra J., et al. Comparison of surgically repaired Achilles tendon tears using platelet-rich fibrin matrices. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:245-251.

33. Becker C., Heidersdorf S., Drewlo S., et al. Efficacy of epidural perineural injections with autologous conditioned serum for lumbar radicular compression: an investigator-initiated, prospective, double-blind, reference-controlled study. Spine. 2007;32(17):1803-1808.

34. Dijs H., Mortier G., Driessens M., et al. A retrospective study of the conservative treatment of tennis elbow. Acta Belg Med Phys. 1990;13:73-77.

35. Anderson B., Kaye S. Treatment of flexor tenosynovitis of the hand (“trigger finger”) with corticosteroids: A prospective study of the response to local injection. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:153-156.

36. Kalaci A., Cakici H., Hapa O., et al. Treatment of plantar fasciitis using four different local injection modalities: A randomized prospective clinical trial. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2009;99(2):108-113.

37. Kerrigan C.L., Stanwix M.G. Using evidence to minimize the cost of trigger finger care. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(6):997-1005.

38. Kleinman M., Gross A. Achilles tendon rupture following steroid injection. Report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:1345-1347.

39. Lambert M.A., Morton R.J., Sloan J.P. Controlled study of the use of local steroid injection in the treatment of trigger finger and thumb. J Hand Surg Br. 1992;17:69-70.

40. Marks M.R., Gunther S.F. Efficacy of cortisone injection in treatment of trigger fingers and thumbs. J Hand Surg Am. 1989;14:722-727.

41. Taras J.S., Raphael J.S., Pan W.T., et al. Corticosteroid injections for trigger digits: Is intrasheath injection necessary? J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23:717-722.

42. Jeyapalan K., Choudhary S. Ultrasound-guided injection of triamcinolone and bupivacaine in the management of DeQuervain’s disease. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38(11):1099-1103.

43. Nimigan AS, Ross DC, Gan BS. Steroid injections in the management of trigger fingers. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 206;85(1):36-43.

44. Sibbitt W.L., Eaton R.P. Corticosteroid responsive tenosynovitis is a common pathway for limited joint mobility in the diabetic hand. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:931-936.

45. O’Brien M. Functional anatomy and physiology of tendons. Clin Sports Med. 1992;11:505-520.

46. Sawaizumi T., Nanno M., Ito H. DeQuervain’s disease: Efficacy of intrasheath triamcinolone injection. Int Orthop. 2007;31(2):265-268.

47. Price R., Sinclair H., Heinrich I., et al. Local injection treatment of tennis elbow-hydrocortisone, triamcinolone and lignocaine compared. Br J Rheumatol. 1991;30:39-44.

48. Leadbetter W.B. Cell-matrix response in tendon injury. Clin Sports Med. 1992;11:533-578.

49. DaCruz D.J., Geeson M., Allen M.J., Phair I. Achilles paratendonitis: An evaluation of steroid injection. Br J Sports Med. 1988;22:64-65.

50. Rineer C.A., Ruch D.S. Elbow tendinopathy and tendon ruptures: epicondylitis, biceps and triceps ruptures. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(3):566-576.

51. Adebajo A.O., Nash P., Hazleman B.L. A prospective double blind dummy placebo controlled study comparing triamcinolone hexacetonide injection with oral diclofenac 50 mg TDS in patients with rotator cuff tendinitis. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:1207-1210.

52. Galloway M.T., Jokl P., Dayton O.W. Achilles tendon overuse injuries. Clin Sports Med. 1992;11:771-782.

53. Shrier I., Matheson G.O., Kohl H.W.3rd. Achilles tendonitis: Are corticosteroid injections useful or harmful? Clin J Sports Med. 1996;6:245-250.

54. Cyriax J. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine: Vol. 2. Treatment by Manipulation Massage and Injection. London: Baillière Tindall; 1980.

55. Vaccaro J.P., Sauser D.D., Beals R.K. Iliopsoas bursa imaging: Efficacy in depicting abnormal iliopsoas tendon motion in patients with internal snapping hip syndrome. Radiology. 1995;197:853-856.

56. Warwick R., Williams P.L. Gray’s Anatomy, 36th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1980.