Chapter 439 Systemic Hypertension

Definition of Hypertension

The definition of hypertension in adults is BP ≥140/90 mm Hg, regardless of body size, sex, or age. This is a functional definition relating level of BP elevation with the likelihood of subsequent cardiovascular events. Since hypertension-associated cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction or stroke usually do not occur in childhood, the definition of hypertension in children is statistical rather than functional. The National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents published the Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents (Fourth Report) in 2004. This report established normal values based on the normative distribution of BP in healthy children and included tables with systolic and diastolic values for the 50th, 90th, 95th, and 99th percentile by age, sex, and height percentile. These normative tables can be obtained free online at www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/child_tbl.htm. The Fourth Report defined hypertension as average systolic blood pressure (SBP) and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) that is ≥95th percentile for age, sex, and height on ≥3 occasions. Prehypertension was defined as average SBP or DBP that are ≥90th percentile but <95th percentile. In adolescents beginning at age 12 yr, prehypertension is defined as BP between 120/80 mm Hg and the 95th percentile. A child with BP levels ≥95th percentile in a medical setting but normal BP outside of the office has white coat hypertension.

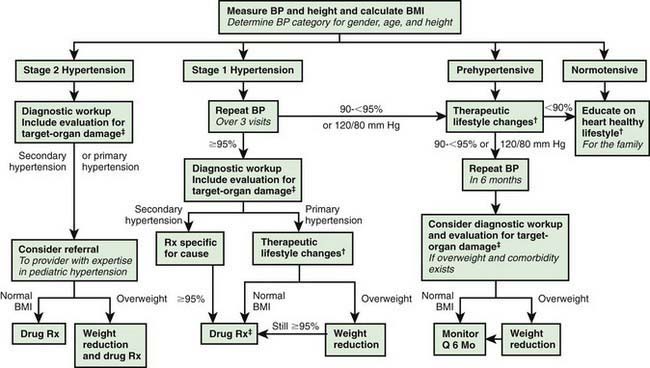

The Fourth Report further recommended that if BP is ≥95th percentile, then the hypertension should be staged. Children with BP between the 95th and 99th percentile plus 5 mm Hg are categorized as stage 1 hypertension, and children with BP above the 99th percentile plus 5 mm Hg have stage 2 hypertension. Stage 1 hypertension, if asymptomatic and without target organ damage, allows time for evaluation before starting treatment; whereas stage 2 hypertension calls for more prompt evaluation and pharmacologic therapy (Fig. 439-1).

Etiology and Pathophysiology

BP is the product of cardiac output and peripheral vascular resistance. An increase in either cardiac output or peripheral resistance results in an increase in BP; if one of these factors increases while the other decreases, BP may not increase. When hypertension is the result of another disease process, it is referred to as secondary hypertension. When no identifiable cause can be found, it is referred to as primary (essential) hypertension. Many factors, including heredity, diet, stress, and obesity, may play a role in the development of primary hypertension. Secondary hypertension is most common in infants and younger children. In general, the younger the child, the higher the BP and the presence of symptoms related to hypertension, the more likely there will be an underlying secondary cause of hypertension. Many childhood diseases can be responsible for chronic hypertension (Table 439-1) or acute/intermittent hypertension (Table 439-2). The most likely cause varies with age. Hypertension in the premature infant is most often associated with umbilical artery catheterization and renal artery thrombosis. Hypertension during early childhood may be due to renal disease, coarctation of the aorta, endocrine disorders, or medications. In older school-aged children and adolescents, primary hypertension becomes increasingly common.

Table 439-1 CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH CHRONIC HYPERTENSION IN CHILDREN

RENAL

VASCULAR

ENDOCRINE

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

Table 439-2 CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH TRANSIENT OR INTERMITTENT HYPERTENSION IN CHILDREN

RENAL

DRUGS AND POISONS

CENTRAL AND AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

MISCELLANEOUS

Diagnosis

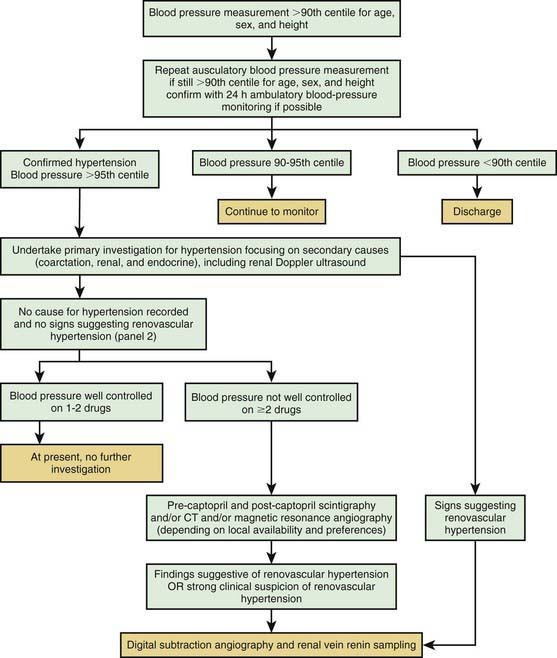

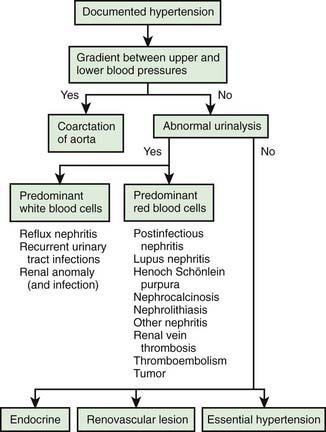

The evaluation of the child with chronic hypertension should be directed toward uncovering potential underlying causes of the hypertension, evaluating for co-morbidities, and screening for evidence of target organ damage. The extent of the evaluation for underlying causes of hypertension depends on the type of hypertension that is suspected. When secondary hypertension is a strong consideration, as in younger children with severe and symptomatic hypertension, an extensive evaluation may be necessary (Fig. 439-2). Alternatively, overweight adolescents with a family history of hypertension who have mild elevations of BP may need only a limited number of tests.

Figure 439-2 Initial diagnostic algorithm in the evaluation of hypertension.

(From Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier, p 222.)

In all cases, a careful history and physical examination are warranted. A family history for early cardiovascular events should be obtained. Growth parameters should be determined to detect evidence of chronic disease. BP should be obtained in all 4 extremities to detect coarctation (thoracic or abdominal) of the aorta. Other features of the physical examination that may provide evidence of an underlying cause of hypertension are noted in Table 439-3. Unless the history and physical examination suggest another cause, children with confirmed hypertension should have an evaluation to detect renal disease, including urinalysis, electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, complete blood count, urine culture, and renal ultrasound. A more complete list of tests to consider in the clinical evaluation of a child with confirmed hypertension is given in Table 439-4.

| PHYSICAL FINDINGS | POTENTIAL RELEVANCE |

|---|---|

| GENERAL | |

| Pale mucous membranes, edema, growth retardation | Chronic renal disease |

| Elfin facies, poor growth, retardation | Williams syndrome |

| Webbing of neck, low hairline, widespread nipples, wide carrying angle | Turner syndrome |

| Moon face, buffalo hump, hirsutism, truncal obesity, striae | Cushing syndrome |

| HABITUS | |

| Thinness | Pheochromocytoma, renal disease, hyperthyroidism |

| Virilization | Congenital adrenal hyperplasia |

| Rickets | Chronic renal disease |

| SKIN | |

| Café-au-lait spots, neurofibromas | Neurofibromatosis, pheochromocytoma |

| Tubers, “ash-leaf” spots | Tuberous sclerosis |

| Rashes | SLE, vasculitis (HSP), impetigo with acute nephritis |

| Pallor, evanescent flushing, sweating | Pheochromocytoma |

| Needle tracks | Illicit drug use |

| Bruises, striae | Cushing syndrome |

| EYES | |

| Extraocular muscle palsy | Nonspecific, chronic, severe |

| Fundal changes | Nonspecific, chronic, severe |

| Proptosis | Hyperthyroidism |

| HEAD AND NECK | |

| Goiter | Thyroid disease |

| CARDIOVASCULAR SIGNS | |

| Absent of diminished femoral pulses, low leg pressure relative to arm pressure | Aortic coarctation |

| Heart size, rate, rhythm; murmurs; respiratory difficulty, hepatomegaly | Aortic coarctation, congestive heart failure |

| Bruits over great vessels | Arteritis or arteriopathy |

| Rub | Pericardial effusion secondary to chronic renal disease |

| PULMONARY SIGNS | |

| Pulmonary edema | Congestive heart failure, acute nephritis |

| Picture of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) | BPD-associated hypertension |

| ABDOMEN | |

| Epigastric bruit | Primary renovascular disease or in association with Williams syndrome, neurofibromatosis, fibromuscular dysplasia, or arteritis |

| Abdominal masses | Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, pheochromocytoma, polycystic kidneys, hydronephrosis |

| NEUROLOGIC SIGNS | |

| Neurologic deficits | Chronic or severe acute hypertension with stroke |

| GENITALIA | |

| Ambiguous, virilized | Congenital adrenal hyperplasia |

HSP, Henoch-Schönlein purpura; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

From Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier, p 200.

Table 439-4 CLINICAL EVALUATION OF CONFIRMED HYPERTENSION

| STUDY OR PROCEDURE | PURPOSE | TARGET POPULATION |

|---|---|---|

| EVALUATION FOR IDENTIFIABLE CAUSES | ||

| History, including sleep history, family history, risk factors, diet, and habits such as smoking and drinking alcohol; physical examination | History and physical examination help focus subsequent evaluation | All children with persistent BP ≥95th percentile |

| BUN, creatinine, electrolytes, urinalysis, and urine culture | R/O renal disease and chronic pyelonephritis | All children with persistent BP ≥95th percentile |

| CBC | R/O anemia, consistent with chronic renal disease | All children with persistent BP ≥95th percentile |

| Renal U/S | R/O renal scar, congenital anomaly, or disparate renal size | All children with persistent BP ≥95th percentile |

| EVALUATION FOR CO-MORBIDITY | ||

| Fasting lipid panel, fasting glucose | Identify hyperlipidemia, identify metabolic abnormalities | Overweight patients with BP at 90th-94th percentile; all patients with BP ≥95th percentile; family history of hypertension or CVD; child with chronic renal disease |

| Drug screen | Identify substances that might cause hypertension | History suggestive of possible contribution by substances or drugs. |

| Polysomnography | Identify sleep disorder in association with hypertension | History of loud, frequent snoring |

| EVALUATION FOR TARGET-ORGAN DAMAGE | ||

| Echocardiogram | Identify LVH and other indications of cardiac involvement | Patients with co-morbid risk factors* and BP 90th-94th percentile; all patients with BP ≥95th percentile |

| Retinal exam | Identify retinal vascular changes | Patients with co-morbid risk factors and BP 90th-94th percentile; all patients with BP ≥95th percentile |

| ADDITIONAL EVALUATION AS INDICATED | ||

| ABPM | Identify white coat hypertension, abnormal diurnal BP pattern, BP load | Patients in whom white coat hypertension is suspected, and when other information on BP pattern is needed |

| Plasma renin determination | Identify low renin, suggesting mineralocorticoid-related disease | Young children with stage 1 hypertension and any child or adolescent with stage 2 hypertension |

| Positive family history of severe hypertension | ||

| Renovascular imaging Isotopic scintigraphy (renal scan) MRA Duplex Doppler flow studies 3-Dimensional CT |

Identify renovascular disease | Young children with stage 1 hypertension and any child or adolescent with stage 2 hypertension |

| Arteriography: DSA or classic | ||

| Plasma and urine steroid levels | Identify steroid-mediated hypertension | Young children with stage 1 hypertension and any child or adolescent with stage 2 hypertension |

| Plasma and urine catecholamines | Identify catecholamine-mediated hypertension | Young children with stage 1 hypertension and any child or adolescent with stage 2 hypertension |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CBC, complete blood count; R/O, rule out; U/S, ultrasound.

* Co-morbid risk factors also include diabetes mellitus and kidney disease.

From National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents, Pediatrics 114(2 Suppl 4th Report):562, 2004.

Renovascular hypertension is often associated with other diseases (Table 439-5) but may be isolated. Doppler ultrasonography as well as captopril renography and MR or spiral CT angiography are helpful screening tests, but invasive angiography is often needed especially to detect intrarenal arterial stenosis (Fig. 439-3).

Table 439-5 CAUSES OF RENOVASCULAR HYPERTENSION IN CHILDREN

From Tullus K, Brennan E, Hamilton G, et al: Renovascular hypertension in children, Lancet 371:1453–1463, 2008; p 1454, Panel 1.

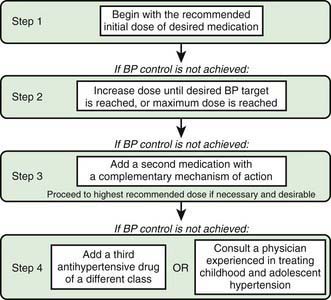

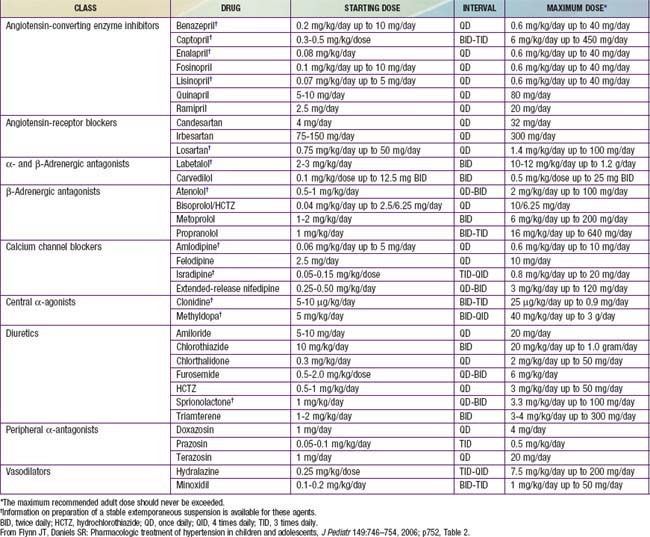

Treatment

The Fourth Report recommended a management algorithm for children with confirmed hypertension according to whether the child has prehypertension, stage 1 hypertension, or stage 2 hypertension (Figs. 439-1 and 439-4). The mainstay of therapy for children with asymptomatic mild hypertension without evidence of target organ damage is therapeutic lifestyle modification with dietary changes and regular exercise. Weight loss is the primary therapy in obesity-related hypertension. It is recommended that all hypertensive children have a diet increased in fresh fruits, fresh vegetables, fiber, and nonfat dairy and reduced in sodium. In addition, regular aerobic physical activity for at least 30-60 min on most days along with a reduction of sedentary activities to less than 2 hr per day is recommended. Indications for pharmacologic therapy include symptomatic hypertension, secondary hypertension, hypertensive target organ damage, diabetes (types 1 and 2), and persistent hypertension despite nonpharmacologic measures (Table 439-6). When indicated, antihypertensive medication should be initiated as a single agent at low dose (see Fig. 439-4). The dose can then be increased until the goal BP is achieved. Once the highest recommended dose is reached or if the child develops side effects, then a second drug from a different class can be added. Acceptable drug classes for use in children include ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics. Details on recommended doses of different classes of antihypertensive medications for children can be found in the Fourth Report available free online at www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/prof/heart/hbp/hbp_ped.pdf.

Figure 439-4 Stepped-care approach to antihypertensive therapy in children and adolescents. BP, blood pressure.

(From Flynn JT, Daniels SR: Pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in children and adolescents, J Pediatr 149:746–754, 2006; p 751, Fig 2.)

Table 439-6 RECOMMENDED DOSES FOR SELECTED ANTIHYPERTENSIVE AGENTS FOR USE IN HYPERTENSIVE CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

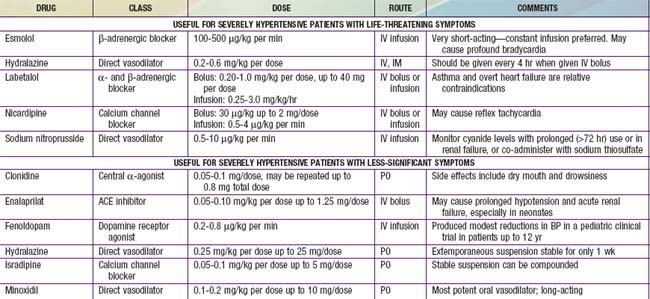

Severe, symptomatic hypertension is a hypertensive emergency that is often accompanied by cardiac failure, retinopathy, renal failure, encephalopathy, and seizures. Intravenous administration is often preferred so that the fall in BP can be carefully titrated (Table 439-7). Drug choices include labetalol, nicardipine, and sodium nitroprusside. Because too rapid a reduction in BP may interfere with adequate organ perfusion, a stepwise reduction in pressure should be planned. In general, the pressure should be reduced by 10% in the 1st hour, and 15% more in the next 3-12 hr, but not to normal during the acute phase of treatment. Hypertensive urgencies, usually accompanied by few serious symptoms such as severe headache or vomiting, can be treated either orally or intravenously. The Fourth Report also includes detailed information on antihypertensive drugs used for the management of severe hypertension in children.

Treatment of secondary hypertension must also focus on the underlying disease such as chronic renal disease, hyperthyroidism, adrenal-genital syndrome, pheochromocytoma, coarctation of the aorta, or renovascular hypertension. The treatment of renovascular stenosis includes antihypertensive medications, angioplasty, or surgery (Fig. 439-5). If bilateral renovascular hypertension or renovascular disease in a solitary kidney is suspected, drugs acting on the renin-angiotensin axis are usually contraindicated because they may reduce glomerular filtration rates and produce renal failure. Balloon angioplasty or surgical revascularization should then be attempted.

Birkenhäger WH, Staessen JA. Dual inhibition of the renin system by aliskiren and valsartan. Lancet. 2007;370:195-196.

Chesney RW, Jones DP. Is there a role for β-adrenergic blockers in treating hypertension in children? J Pediatr. 2007;150:121-122.

Douma S, Petidis K, Doumas M. Prevalence of primary hyperaldosteronism in resistant hypertension: a retrospective observational study. Lancet. 2008;371:1921-1926.

Doumas M, Douma S. Interventional management of resistant hypertension. Lancet. 2009:1228-1230.

Ernst ME, Moser M. Use of diuretics in patients with hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2153-2162.

Falkner B. Hypertension in children. Pediatr Ann. 2006;35:795-801.

Falkner B, Gidding SS, Portman R, et al. Blood pressure variability and classification of prehypertension and hypertension in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2008;122:238-242.

Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1811-1821.

Flynn JT. Hypertension in the young: epidemiology, sequelae and therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008 Nov 7.

Flynn JT, Daniels SR. Pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2006;149:746-754.

Flynn JT, Falkner BE. Should the current approach to the evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure in children be changed? J Pediatr. 2009;155:157-158.

Friedman A. Blood pressure screening in children: do we have this right? J Pediatr. 2008;153:452-453.

Hammer F, Stewart PM. Investigating hypertension in a young person. BMJ. 2009;338:885-886.

Hansen MI, Gunn PW, Kaelber DC. Under diagnosis of hypertension in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2007;298:874-879.

Ishikura K, Ikeda M, Hamasaki Y, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in children: Its high prevalence and more extensive imaging findings. Am J Kid Dis. 2006;48:231-238.

Kaelber DC, Pickett F. Simple table to identify children and adolescents needing further evaluation of blood pressure. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e972-e974.

Lande MB, Flynn JT. Treatment of hypertension in children and adolescents. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007 Aug 10.

Li R, Richey PA, DiSessa TG, et al. Blood aldosterone-to-renin ratio, ambulatory blood pressure, and left ventricular mass in children. J Pediatr. 2009;155:170-175.

McNiece KL, Poffenbarger TS, Turner JL, et al. Prevalence of hypertension and pre-hypertension among adolescents. J Pediatr. 2007;150:640. 4, 644.e1

2009 The Medical Letter: Treatment guideline—drugs for hypertension. Med Lett. 2009:77.

Messerli FH, Williams B, Ritz E. Essential hypertension. Lancet. 2007;370:591-602.

National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004 Aug;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555-576.

Portman RJ, McNiece KL, Swinford RD, et al. Pediatric hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, management, and treatment for the primary care physician. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2005;35:262-294.

Tullus K, Brennan E, Hamilton G, et al. Renovascular hypertension in children. Lancet. 2008;371:1453-1463.

Urbina EM. Removing the mask: the danger of hidden hypertension. J Pediatr. 2008;152:455-456.

Urbina E, Alpert B, Flynn J, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in children and adolescents: recommendations for standard assessment: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in Youth Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and the council for High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2008;52:433-451.

Waeber B, Feihl F. Blood-pressure reduction with LCZ696. Lancet. 2010;375:1228-1229.

Weber MA, Black H, Bakris G, et al. A selective endothelin-receptor antagonist to reduce blood pressure in patients with treatment-resistant hypertension: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1423-1430.

Wiesen J, Adkins M, Fortune S, et al. Evaluation of pediatric patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension: yield of diagnostic testing. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e988-e993.

Williams B. High blood pressure in young people and premature death. BMJ. 2011;342:450-451.