Chapter 110 Menstrual Problems

Menstrual Irregularities

Menstrual cycle irregularities are described according to variation in frequency of menses, amount, and both frequency and amount (Table 110-1). Most menstrual cycle abnormalities are explained by maturation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, although organic pathology should be considered and excluded in a logical and cost-effective manner. A complete history for evaluating a patient with menstrual dysfunction should include questions specifically related to puberty and menstrual patterns, a family history of gynecologic problems and maternal onset of menarche, and a medical history noting hospitalizations, chronic illness, medication or substance use, and infections. The related associations of weight change, nutrition, exercise, and sports participation can be critically important in considering a differential diagnosis. Regardless of the age of the adolescent, an appropriate history of any type of sexual activity should be elicited, and the pediatrician should be cognizant of the need to rule out sexual abuse as an issue in very young adolescents when other findings suggest sexual activity.

Table 110-1 TERMS FOR MENSTRUAL CYCLE IRREGULARITIES

VARIATIONS IN FREQUENCY

VARIATIONS IN AMOUNT

VARIATIONS IN AMOUNT AND DURATION

From Blythe MI: Common menstrual problems of adolescence, Adolesc Med 8:87–109, 1997.

Psychogenic factors have been implicated in amenorrhea. It is often difficult to separate psychologic from nutritional factors because weight loss is a common confounding variable in many of these situations, such as depression (Chapter 24), anorexia nervosa (Chapter 26), or stress.

110.1 Amenorrhea

Differential Diagnosis

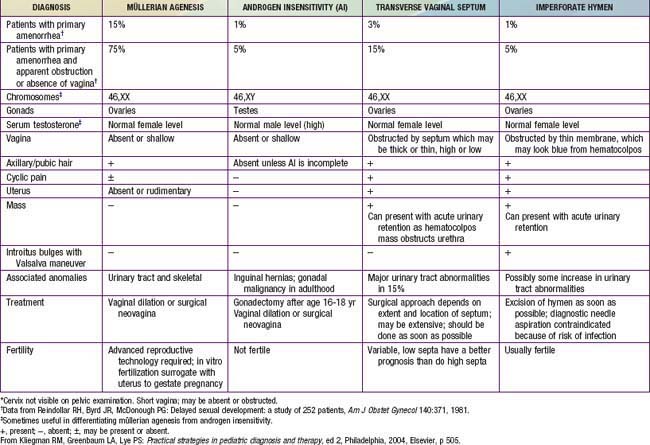

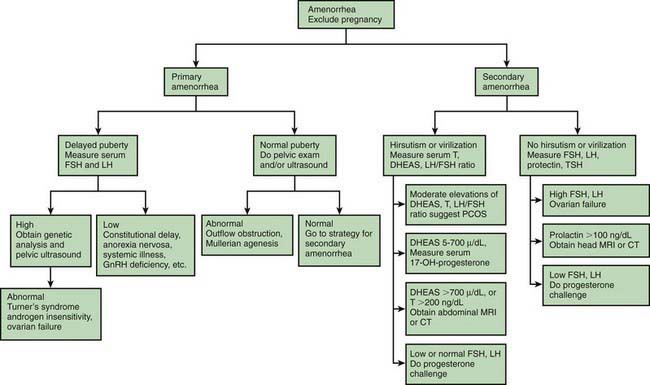

In primary amenorrhea, defined as failure for menstruation to begin, chromosomal or congenital abnormalities, such as gonadal dysgenesis, triple X syndrome, isochromosomal abnormalities, testicular feminization syndrome, and, rarely, true hermaphroditism, should be considered in addition to the conditions that cause secondary amenorrhea (Table 110-2). Elevated levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) suggest primary gonadal failure, and chromosome analysis often elucidates its cause. When primary amenorrhea occurs with otherwise normal progression of pubertal development, a structural anomaly of the müllerian duct system (Chapter 548) should be suspected. Imperforate hymen is most the common disorder of müllerian duct descent and is associated with recurrent (monthly) abdominal pain and, after some time has passed, a midline, lower abdominal mass, which is the blood-filled vagina, and is called hematocolpos. Diagnosis is made by inspection of the introitus, revealing a bulging hymen with bluish discoloration. If the obstruction is at the level of the cervix, the blood-filled uterus (hematometrium) is apparent on bimanual examination or ultrasonography. Agenesis of the cervix or uterus is rare but occurs in association with sacral agenesis.

Primary or secondary amenorrhea may also be caused by chronic illness, particularly that associated with malnutrition or tissue hypoxia, such as diabetes mellitus, inflammatory bowel disease, cystic fibrosis, or cyanotic congenital heart disease. In most cases, the illness has been diagnosed previously, but, occasionally, the amenorrhea is its first manifestation. Pregnancy is a common cause of secondary and occasionally primary amenorrhea. Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) (Chapter 580.2) is one of the most common endocrine disorders affecting 4-6% of premenopausal women and presents with menstrual abnormalities that range from amenorrhea to dysfunctional uterine bleeding. The criterion for the diagnosis of PCOS is menstrual irregularity in the face of androgen excess with either hirsutism, acne, or increased serum androgens. When the androgen excess is coupled with insulin resistance and acanthosis nigricans, the term HAIR-AN syndrome is used. A central nervous system (CNS) tumor, most commonly a craniopharyngioma, may present with amenorrhea. Prolactinomas, although rare, are the most common pituitary tumor in adolescence. Abnormalities of the thyroid gland, typically hyperthyroidism, may first be suspected by delayed sexual maturation or amenorrhea, even in the absence of other signs and symptoms. Hypothyroidism may cause precocious puberty but may also be associated with delayed puberty or abnormal uterine bleeding. Anorexia nervosa, which may present with either primary or secondary amenorrhea, is occasionally confused with hyperthyroidism because of weight loss, hyperactivity, and personality changes seen in both entities. Amenorrhea is one of the components of the female athlete triad in association with disordered eating and low bone mass (Chapter 682). Ballerinas, gymnasts, and runners may be at disproportionate risk of this triad. Ingestion of drugs, both legal and illegal, may cause amenorrhea and, in the case of phenothiazines, even a false-positive urine pregnancy test. Some drugs, including phenothiazines and certain antihypertensive agents, may cause galactorrhea, further mimicking pregnancy. Pertinent findings on physical exam include signs of androgen excess, such as obesity, acne, hirsutism, and clitoromegaly, along with excessive thinness, galactorrhea, and thyromegaly. Adolescents with amenorrhea who diet, whether or not they meet diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa, are at risk for low bone density.

Laboratory Findings

The approach to the clinical evaluation of amenorrhea follows a stepwise progression initiated by the history and physical examination. The pregnancy test, usually a qualitative measure of urinary chorionic gonadotropin, is the key laboratory test to perform in the evaluation of amenorrhea regardless of the history or sexual activity given by the patient (Fig. 110-1). The next step for laboratory determinations follows the scheme in which gonadotropin levels. The measurement of FSH is critical in determining whether chromosomal abnormalities (with FSH elevation >25 mIU/mL) or other endocrinopathies or CNS tumors (with normal or low FSH <5 mIU/mL) are present. Prolonged amenorrhea (>6 mo) or persistent oligomenorrhea (<6 menses in past year) without an explanation should prompt the measurement of thyroid-stimulating hormone, FSH, LH, and prolactin levels, even in the face of a normal progesterone challenge. Elevated LH and normal FSH levels require the measurement of androgen excess even in the absence of virilization. An LH : FSH ratio >3 and elevated free testosterone and DHEAS (dihydroepiandrosterone sulfate) levels are common in adolescents with PCOS. Hyperinsulinemia is a characteristic feature of PCOS, and there is an increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Elevated DHEAS may indicate the source of excess androgen to disorders in the adrenal gland. An elevated prolactin level or other clinical features suggesting a CNS tumor should be followed up with cranial CT scan or, preferably, MRI.

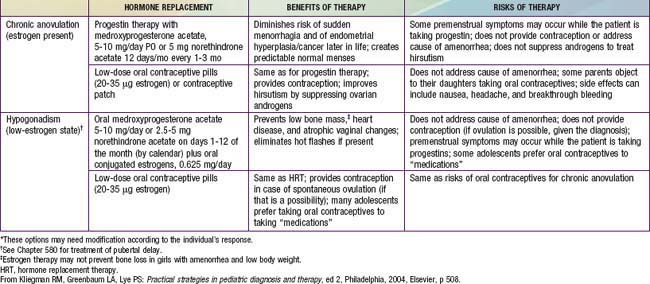

Treatment

Determination of the cause of amenorrhea may permit the initiation of corrective intervention. When the disorder is not amenable to remediation, consideration should be given to establishing regular pseudomenses to allow the adolescent to feel like her peers (Table 110-3). Counseling the adolescent whose diagnosis will render her unable to conceive is especially challenging, and support and follow-up are important. If the result of a vaginal smear is positive for estrogen effect, regular cycling can be accomplished using medroxyprogesterone in a dose of 10 mg orally for 10-12 days at least every other month. Combination norgestimate- or drospirenone-containing oral contraceptives can also be used for this purpose in patients with PCOS. In a patient with gonadal dysgenesis, conjugated estrogens must be given first (Premarin in an oral dose of 0.3 mg and increased to 1.25 mg) for feminization to progress. This is followed by medroxyprogesterone, 10 mg orally on days 10-21 of the cycle. Lifestyle changes, particularly weight reduction and insulin sensitizers, specifically metformin, have been shown to re-establish menses and ovulation is some patients, but symptoms return when the medication is discontinued.

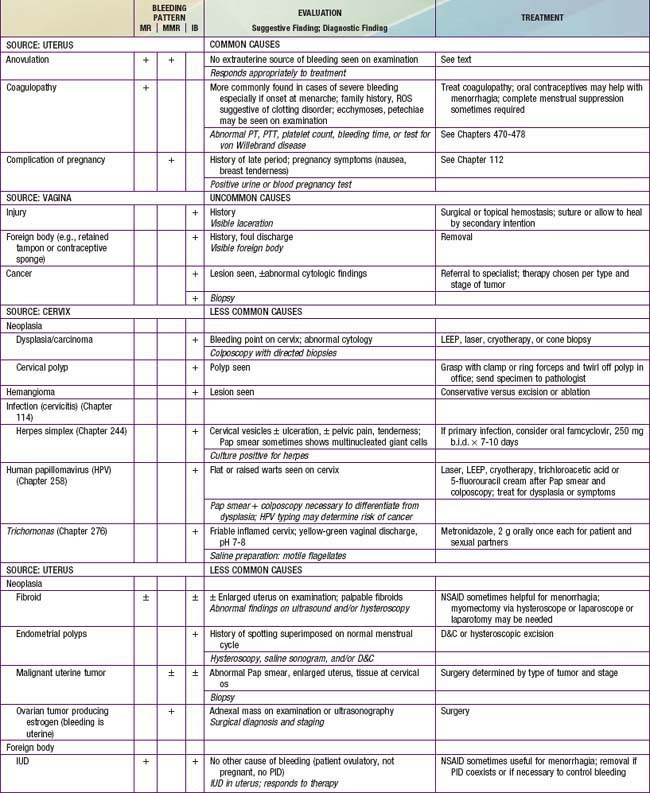

110.2 Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Differential Diagnosis

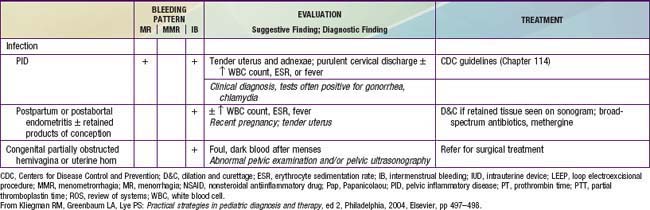

Among U.S. adolescents admitted to the hospital for menorrhagia, anovulation was the most common cause (46%), followed by hematologic causes (33%), infection (11%), and chemotherapy (11%). In Sweden, a study among ~1,000 adolescents revealed that 73% had ≥1 episode of bleeding problems, with one third experiencing menorrhagia. Organic lesions are found in about 9% of 10-20 yr old young women; the most common include ectopic pregnancy, threatened abortion, and endometritis/salpingitis. The key distinguishing feature between anovulatory uterine bleeding and that due to organic disorders listed previously is that the latter are characterized by pain whereas anovulatory bleeding is usually painless. Table 110-4 lists the extensive differential diagnosis; studies of severe cases that require hospitalization report coagulation disorders (idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, von Willebrand disease, Glanzmann disease, leukemia), hypothyroidism, thalassemia major, Fanconi syndrome, and rheumatoid arthritis as the more frequent diagnoses. Medications may cause abnormal uterine bleeding; these include estrogens, progestins, androgens, prolactin, and drugs that cause prolactin release (estrogens, phenothiazines, tricyclic antidepressants, metoclopramide), and anticoagulants (heparin, warfarin, aspirin, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]).

James AH, Kouides PA, Abdul-Kadir R, et al. Von Willebrand disease and other bleeding disorders in women: consensus on diagnosis and management from an international expert panel. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:e1-e8.

Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Treatments for heavy menstrual bleeding. Br Med J. 2003;327:1243-1244.

Mitan LA, Slap GB. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. In: Neinstein LS, Gordon CM, Katzman DK, et al, editors. Adolescent health care: a practical guide. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:687-690.

Palep-Singh M, Prentice A. Epidemiology of abnormal uterine bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;21:887-890.

110.3 Dysmenorrhea

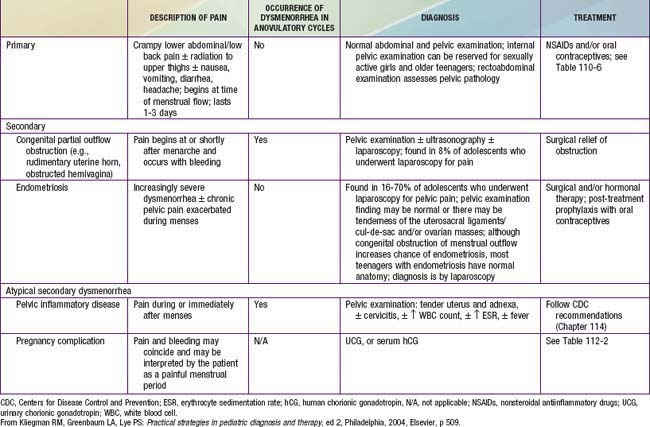

Painful menstrual cramps are experienced by nearly 65% of postmenarchal teenagers in the USA. More than 10% of this group suffers sufficiently to miss school, making dysmenorrhea the leading cause of short-term school absenteeism in female adolescents. Dysmenorrhea may be primary or secondary. Primary dysmenorrhea is characterized by the absence of any specific pelvic pathologic condition and is the more commonly occurring form (Table 110-5). Prostaglandins F2 and E2, produced by the endometrium, stimulate local vasoconstriction and myometrial contractions, thereby producing pain. Secondary dysmenorrhea results from an underlying structural abnormality of the cervix or uterus, a foreign body such as an intrauterine device, endometriosis, or endometritis. Endometriosis is a condition in which implants of endometrial tissue are found at ectopic locations within the peritoneal cavity. Characteristically, there is severe pain at the time of menses; its specific location depends on the site of the implants.

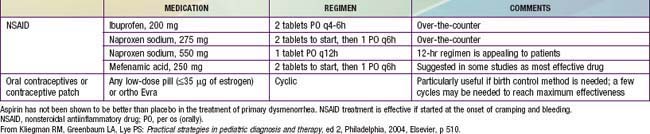

With its very high prevalence, primary dysmenorrhea should be presumed on initial presentation. Because adolescents suffering from dysmenorrhea have high levels of prostaglandins, they experience symptomatic relief when prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors are administered (Table 110-6). If given before a menstrual period (or shortly after it begins), administration of a rapidly absorbed prostaglandin synthetase inhibitor, such as naproxen sodium, is effective in reducing prostaglandin production before they cause pain (2 tablets of 275 mg each taken with the onset of menses and 1 tablet taken every 6-8 hr after that for the 1st 24 hr). Medication is rarely needed beyond the 1st day. For the teenager with dysmenorrhea who requires contraception, combined hormonal therapy in the form of oral contraceptives, the contraceptive patch, or vaginal ring may be indicated. It is not certain whether the beneficial effect of such use derives from the ability of oral contraceptives to inhibit ovulation and thus eliminate progesterone production from the corpus luteum or from their ability to limit endometrial proliferation and therefore the production of prostaglandins.

Proctor M, Farquhar C. Diagnosis and management of dysmenorrheal. BMJ. 2006;332:1134-1138.

Yang H, Liu CZ, Chen X, et al. Systematic review of clinical trials of acupuncture-related therapies for primary dysmenorrheal. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:1114-1122.

Zhu X, Proctor M, Bensoussan A, et al: Chinese herbal medicine for primary dysmenorrhoea, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008(2):CD005288.

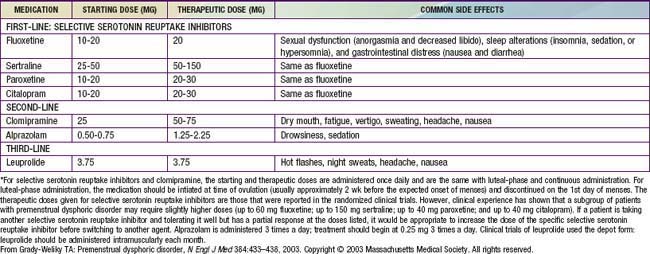

110.4 Premenstrual Syndrome

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS), or the late luteal phase syndrome, is a complex of physical signs and behavioral symptoms occurring during the 2nd half of the menstrual cycle, which may resolve with the onset of menses. Clinical manifestations may include breast fullness and tenderness; bloating; fatigue; headache; increased appetite, especially for sweets and salty foods; irritability and mood swings; depression; inability to concentrate; tearfulness; and violent tendencies. About 30% of women in the reproductive age group and ≥20% adolescents experience PMS; the absence of objective findings makes this difficult to corroborate. It does not relate to the presence of dysmenorrhea, which is much more common in this age group. For the diagnosis of PMS, documentation of symptoms using a special calendar for 2-3 mo should demonstrate the pattern of association with menses. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), particularly mefenamic acid, diuretics, and agnus castus fruit extract have demonstrated some therapeutic efficacy in small trials. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder occurs less commonly, in 3-8% of women of reproductive age and is a more severe form of premenstrual syndrome (Table 110-7), requiring more intensive therapy (Table 110-8).

Table 110-7 CRITERIA FOR PREMENSTRUAL DYSPHORIC DISORDER*

* The criteria are from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. In menstruating women, the luteal phase corresponds to the period between ovulation and the onset of menses, and the follicular phase begins with menses. In nonmenstruating women (e.g., women who have had a hysterectomy), determination of the timing of the luteal and follicular phases are variable.

From Grady-Weliky TA: Premenstrual dysphoric disorder, N Engl J Med 348:433–438, 2003. Copyright © 2003 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Braverman PK. Dysmenorrhea and premenstrual syndrome. In: Neinstein LS, Gordon CM, Katzman DK, et al, editors. Adolescent health care: a practical guide. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:674-686.

Grady-Weliky TA. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:433-438.

Rapkin AJ, Mikacich JA. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder in adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20:455-463.

Rapkin AJ, Winer SA. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: quality of life and burden of illness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9:157-170.

Adams Hillard PJ, Deitch HR. Menstrual disorders in the college female. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:179-197.

American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2245-2249.

Caronia LM, Martin C, Welt CK, et al. Agenetic basis for functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:215-224.

Euling SY, Herman-Giddens PA, Lee PA, et al. Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics. 2008;121:S172-S191.

Fothergill DJ. Common menstrual problems in adolescence. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2010;99:199-202.

Gordon CM, Nelson LM. Amenorrhea and bone health in adolescents and young women. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;15:377-384.

Kives SL, Lacy JA. Normal menstrual physiology. In: Neinstein LS, Gordon CM, Katzman DK, et al, editors. Adolescent health care: a practical guide. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:671-674.

Slap GB. Menstrual disorders in adolescence. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;17:75-92.