Chapter 210 Syphilis (Treponema pallidum)

Epidemiology

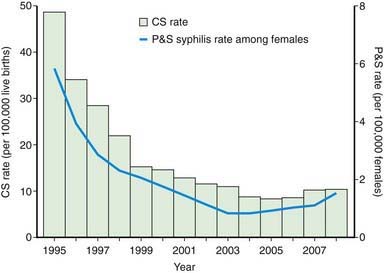

In addition to presentation at sexually transmitted disease clinics, patients with syphilis are increasingly seen by primary care providers in private practice settings. Two forms of syphilis occur in children. Acquired syphilis is transmitted almost exclusively by sexual contact, including oral sexual exposure. Less common modes of transmission include transfusion of contaminated blood or direct contact with infected tissues. After an epidemic resurgence of primary and secondary syphilis in the USA that peaked in 1989, the annual rate declined 90% by 2000. The total number of cases of primary and secondary syphilis has subsequently increased since 2000, particularly among men who have sex with men. Despite a decrease among women for almost a decade, their rates have also increased every year since 2004. By 2007, U.S. reported cases of syphilis had risen for the 7th straight year, a 15% increase from 2006 among men and women. Cases of congenital syphilis rose by 13% in the same time period (Fig. 210-1). Rates in the southern USA and among non-Hispanic blacks are disproportionately high.

(From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National vital statistics system: birth data [website]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/births.htm. Accessed August 25, 2010.) P&S syphilis rates were calculated using bridged race population estimates for 2000-2007 based on 2000 U.S. Census counts. (From CDC Wonder: Bridged-race resident population estimates, United States, state and county, for the years 1990-2008 (website). http://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/bridged-race.html. Accessed August 25, 2010.) (From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Congenital syphilis—United States, 2003-2008, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 59:413–417, 2010.)

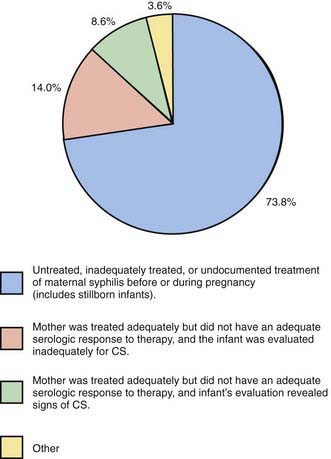

Congenital syphilis results from transplacental transmission of spirochetes. Women with primary and secondary syphilis and spirochetemia are more likely to transmit infection to the fetus than are women with latent infection. Transmission can occur at any stage of pregnancy. The incidence of congenital infection in offspring of untreated or poorly treated infected women remains highest during the first 4 yr after acquisition of primary infection, secondary infection, and early latent disease. Risk factors most commonly associated with congenital syphilis are lack of prenatal care and cocaine drug abuse, unprotected sexual contact, trading of sex for drugs, and poor treatment of syphilis during pregnancy (Fig. 210-2). Confirmed cases of acquired or congenital syphilis should be reported to the local health department.

Clinical Manifestations and Laboratory Findings

Untreated patients develop manifestations of secondary syphilis related to spirochetemia 2-10 wk after the chancre heals. Manifestations of secondary syphilis include a generalized nonpruritic maculopapular rash, notably involving the palms and soles (Fig. 210-3). Pustular lesions can also develop. Condylomata lata, gray-white to erythematous wartlike plaques, can occur in moist areas around the anus and vagina, and white plaques (mucous patches) may be found in mucous membranes. A flulike illness with low-grade fever, headache, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, sore throat, myalgias, arthralgias, and generalized lymphadenopathy is often present. Renal, hepatic, and ophthalmologic manifestations may be present. Meningitis occurs in 30% of patients with secondary syphilis and is characterized by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis and elevated protein level. Patients with meningitis might not show neurologic symptoms. Secondary infection becomes latent within 1-2 mo after onset of rash. Relapses with secondary manifestations can occur during the first year of latency (the early latent period). Late syphilis follows and may be either asymptomatic (late latent) or symptomatic (tertiary). Tertiary disease is marked by neurologic, cardiovascular, and gummatous lesions (nonsuppurative granulomas of the skin and musculoskeletal system resulting from the host’s hypersensitivity reaction).

Figure 210-3 Secondary syphilis. Ham-colored palmar macules on an adolescent with secondary syphilis.

(From Weston WL, Lane AT, Morelli JG: Color textbook of pediatric dermatology, ed 3, St Louis, Mosby, 2002.)

Congenital Infection

Most infected infants are asymptomatic at birth and are identified only by routine prenatal screening. In the absence of treatment, symptoms develop within weeks or months. Among infants symptomatic at birth or in the first months of life, manifestations have traditionally been divided into early and late stages. All stages of congenital syphilis are characterized by a vasculitis, with progression to necrosis and fibrosis. The early signs appear during the first 2 yr of life, and the late signs appear gradually during the first 2 decades. Early manifestations vary and involve multiple organ systems, resulting from transplacental spirochetemia and are analogous to the secondary stage of acquired syphilis (Table 210-1). Hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, and elevated liver enzymes are common. Histologically, liver involvement includes bile stasis, fibrosis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis. Lymphadenopathy tends to be diffuse and resolve spontaneously, although shotty nodes can persist.

| SYMPTOM/SIGN | DESCRIPTION/COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Olympian brow | Bony prominence of the forehead due to persistent or recurrent periostitis |

| Clavicular or Higouménaki sign | Unilateral or bilateral thickening of the sternoclavicular third of the clavicle |

| Saber shins | Anterior bowing of the midportion of the tibia |

| Scaphoid scapula | Convexity along the medial border of the scapula |

| Hutchinson teeth | Peg-shaped upper central incisors; they erupt during 6th yr of life with abnormal enamel, resulting in a notch along the biting surface |

| Mulberry molars | Abnormal 1st lower (6 yr) molars characterized by small biting surface and excessive number of cusps |

| Saddle nose* | Depression of the nasal root, a result of syphilitic rhinitis destroying adjacent bone and cartilage |

| Rhagades | Linear scars that extend in a spoke-like pattern from previous mucocutaneous fissures of the mouth, anus, and genitalia |

| Juvenile paresis | Latent meningovascular infection; it is rare and typically occurs during adolescence with behavioral changes, focal seizures, or loss of intellectual function |

| Juvenile tabes | Rare spinal cord involvement and cardiovascular involvement with aortitis |

| Hutchinson triad | Hutchinson teeth, interstitial keratitis, and 8th nerve deafness |

| Clutton joint | Unilateral or bilateral painless joint swelling (usually involving knees) due to synovitis with sterile synovial fluid; spontaneous remission usually occurs after several wk |

| Interstitial keratitis | Manifests with intense photophobia and lacrimation, followed within weeks or months by corneal opacification and complete blindness. |

| Eighth nerve deafness | May be unilateral or bilateral, appears at any age, manifests initially as vertigo and high-tone hearing loss, and progresses to permanent deafness |

* A perforated nasal septum may be an associated abnormality.

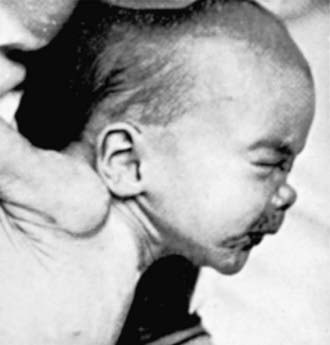

Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia is characteristic. Thrombocytopenia is often associated with platelet trapping in an enlarged spleen. Characteristic osteochondritis and periostitis (Fig. 210-4) and a mucocutaneous rash (Fig. 210-5A, B) manifesting with erythematous maculopapular or vesiculobullous lesions followed by desquamation involving hands and feet (see Fig. 210-5C) are common. Mucous patches, persistent rhinitis (snuffles), and condylomatous lesions (Fig. 210-6) are highly characteristic features of mucous membrane involvement and contain abundant spirochetes. Blood and moist open lesions from infants with congenital syphilis and children with acquired primary or secondary syphilis are infectious until 24 hours of appropriate treatment.

Figure 210-5 A and B, Papulosquamous plaques in 2 infants with syphilis. C, Desquamation on the palm of a newborn’s hand.

(A and B, From Eichenfeld LF, Frieden IJ, Esterly NB, editors: Textbook of neonatal dermatology, Philadelphia, 2001, WB Saunders, p 196. C, Courtesy of Dr. Patricia Treadwell.)

Figure 210-6 Perianal condylomata lata.

(From Karthikeyan K, Thappa DM: Early congenital syphilis in the new millennium, Pediatr Dermatol 19:275–276, 2002.)

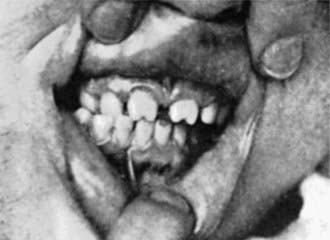

Late manifestations (children >2 years of age) are rarely seen in developed countries. These result primarily from chronic granulomatous inflammation of bone, teeth, and CNS and are summarized in Table 210-1. Skeletal changes are due to persistent or recurrent periostitis and associated thickening of the involved bone. Dental abnormalities such as Hutchinson teeth (Fig. 210-7) are common. Defects in enamel formation lead to repeated caries and eventual tooth destruction. Saddle nose (Fig. 210-8) is a depression of the nasal root and may be associated with a perforated nasal septum.

Other late manifestations of congenital syphilis can manifest as hypersensitivity phenomena. These include unilateral or bilateral interstitial keratitis and the Clutton joint (see Table 210-1). Other common ocular manifestations include choroiditis, retinitis, vascular occlusion, and optic atrophy. Soft tissue gummas (identical to those of acquired disease) and paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria are rare hypersensitivity phenomena.

Diagnosis

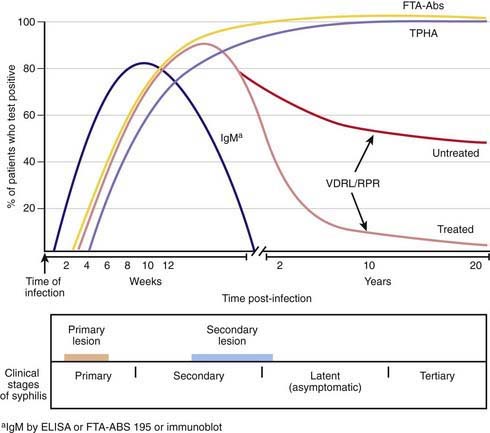

The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests are sensitive nontreponemal tests that detect antibodies against phospholipid antigens on the treponeme surface that cross react with mammalian cardiolipin-lecithin-cholesterol antigens. The quantitative results of these tests are helpful in screening and in monitoring therapy. Titers increase with active disease, including treatment failure or reinfection, and decline with adequate treatment (Fig. 210-9). Nontreponemal tests usually become nonreactive within 1 yr of adequate therapy for primary syphilis and within 2 yr of adequate treatment for secondary disease. Uncommonly some patients become serofast (nontreponemal titers persisting at low levels for long periods). In congenital infection, these tests become nonreactive within a few months after adequate treatment. Certain conditions such as infectious mononucleosis and other infections, connective tissue diseases, and pregnancy can give false-positive VDRL results. False-positive results are less common with the use of purified cardiolipin-lecithin-cholesterol antigen. All positive maternal serologic tests for syphilis, regardless of titer, necessitate thorough investigation. Antibody excess can give a false-negative reading unless the serum is diluted (prozone effect). False-negative results can also occur in early primary syphilis, in latent syphilis of long duration, and in late congenital syphilis.

Treponemal tests traditionally are used to confirm diagnosis and measure specific T. pallidum antibody and include the T. pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA), the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, and the T. pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) test. Treponemal antibody titers become positive soon after initial infection and usually remain positive for life, even with adequate therapy (see Fig. 210-9). These antibody titers do not correlate with disease activity. Traditionally they are useful for diagnosis of a 1st episode of syphilis and for distinguishing false-positive results of nontreponemal antibody tests but cannot accurately identify length of time of infection, response to therapy, or reinfection.

Congenital Syphilis

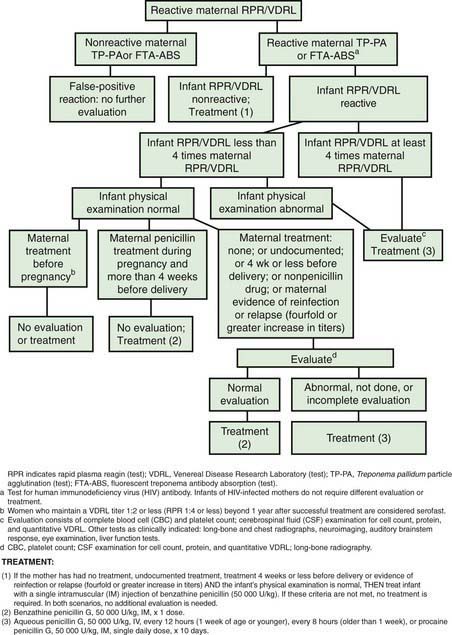

Diagnosis of congenital syphilis requires thorough review of maternal testing, treatment, and the dynamics of response. Proactive evaluation and treatment of exposed neonates is critical (Fig. 210-10 and Table 210-2). Symptomatic infants should be thoroughly evaluated and treated. Guidelines for evaluating and managing asymptomatic infants considered at risk for congenital syphilis because the maternal nontreponemal and treponemal serology is positive are shown in Table 210-3.

Figure 210-10 Algorithm for evaluating and treating infants born to mothers with reactive serologic tests for syphilis.

(From American Academy of Pediatrics: Red book: 2009 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, ed 28, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2009, American Academy of Pediatrics, p 645.)

Table 210-2 CLUES THAT SUGGEST A DIAGNOSIS OF CONGENITAL SYPHILIS*

| EPIDEMIOLOGIC BACKGROUND | CLINICAL FINDINGS |

|---|---|

* Arranged in decreasing order of confidence of diagnosis.

Modified from Remington JS, Klein JO, Wilson CB, et al, editors: Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders, p 556.

Table 210-3 RECOMMENDED MANAGEMENT OF NEONATES (≤1 MO OF AGE) BORN TO MOTHERS WITH SEROLOGIC TESTS FOR SYPHILIS

| CLINICAL STATUS | EVALUATION (IN ADDITION TO PHYSICAL EXAMINATION AND QUANTITATIVE NONTREPONEMAL TESTING) | ANTIMICROBIAL THERAPY* |

|---|---|---|

| Proven or highly probable disease† | CSF analysis for VDRL, cell count, and protein CBC and platelet count Other tests as clinically indicated (e.g., long-bone radiography, liver function tests, ophthalmologic examination) |

Aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 100 000-150 000 U/kg/day, administered as 50,000 U/kg/dose IV q12hr during the first 7 days of life and 18hr thereafter for a total of 10 days or Penicillin G procaine, 50,000 U/kg/day IM in a single dose × 10 days |

| Normal physical examination and serum quantitative nontreponemal titer ≤4 times the maternal titer: | ||

| a) (i) Mother was not treated or inadequately treated or has no documented treatment; (ii) mother was treated with erythromycin or other nonpenicillin regimen; (iii) mother received treatment ≤4 wk before delivery; (iv) maternal evidence of reinfection or relapse (<4-fold decrease in titers) | CSF analysis for VDRL, cell count, and protein§ CBC and platelet count§ Long-bone radiography§ |

Aqueous crystalline penicillin G IV × 10 days§ or Penicillin G procaine‡ 50,000 U/kg IM in a single dose × 10 days§ or Penicillin G benzathine‡ 50,000 U/kg IM in a single dose§ |

| b) (i) Adequate maternal therapy given >4 wk before delivery; (ii) mother has no evidence of reinfection or relapse | None | Clinical, serologic follow-up, and penicillin G benzathine 50,000 U/kg IM in a single dose‖ |

| c) Adequate therapy before pregnancy and mother’s nontreponemal serologic titer remained low and stable during pregnancy and at delivery | None | None¶ |

CBC, complete blood cell count; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

* If >1 day of therapy is missed, the entire course should be restarted.

† Abnormal physical examination, serum quantitative nontreponemal titer that is fourfold greater than the mother’s titer, or positive result of dark-field or fluorescent antibody test of body fluid(s).

‡ Penicillin G benzathine and penicillin G procaine are approved for IM administration only.

§ A complete evaluation (CSF analysis, bone radiography, CBC) is not necessary if 10 days of parenteral therapy is administered, but it may be useful to support a diagnosis of congenital syphilis. If a single dose of penicillin G benzathine is used, then the infant must be evaluated fully, results of the full evaluation must be normal, and follow-up must be certain. If any part of the infant’s evaluation is abnormal or not performed or if the CSF analysis is uninterpretable, the 10-day course of penicillin is required.

‖ Some experts would not treat the infant but would provide close serologic follow-up.

¶ Some experts would treat with penicillin G benzathine, 50,000 U/kg, as a single IM injection, if follow-up is uncertain.

From American Academy of Pediatrics: Red book: 2009 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, ed 28, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2009, American Academy of Pediatrics, p 645.

Treatment

T. pallidum remains extremely sensitive to penicillin, with no evidence of emerging penicillin resistance, and thus penicillin remains the treatment drug of choice (Tables 210-3 and 210-4). Parenteral penicillin G is the only documented effective treatment for congenital syphilis, syphilis during pregnancy, and neurosyphilis. Aqueous crystalline penicillin G is preferred over procaine penicillin, because it better achieves and sustains the minimum concentration of 0.018 µg/mL (0.03 U/mL) needed for 7-10 days to achieve treponemicidal levels. Although nonpenicillin regimens are available to the penicillin-allergic patient, desensitization followed by standard penicillin therapy is the most reliable strategy. An acute systemic febrile reaction called the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (due to massive release of endotoxin-like antigens during bacterial lysis) occurs in 15-20% of patients with acquired or congenital syphilis treated with penicillin. It is not an indication for discontinuing penicillin therapy.

Table 210-4 RECOMMENDED TREATMENT FOR SYPHILIS IN PATIENTS >1 MONTH OF AGE

| STATUS | CHILDREN | ADULTS |

|---|---|---|

| Congenital syphilis | Aqueous crystalline penicillin G 200 000-300 000 U/kg/day IV administered as 50,000 U/kg 14-6hr × 10 days* | |

| Primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis† | Penicillin G benzathine,‡ 50,000 U/kg, IM, up to the adult dose of 2.4 million U in a single dose | Penicillin G benzathine,‡ 2.4 million U IM in a single dose or If allergic to penicillin and not pregnant, doxycycline 100 mg PO bid × 14 days or Tetracycline 500 mg PO qid × 14 days |

| Late latent syphilis§ or syphilis of unknown duration | Penicillin G benzathine,‡ 50,000 U/kg IM up to the adult dose of 2.4 million U, administered as 3 single doses at 1-wk intervals (total 150,000 U/kg, up to the adult dose of 7.2 million U) | Penicillin G benzathine‡ 7.2 million U total administered as 3 doses of 2.4 million U IM, each at 1-wk intervals or If allergic to penicillin and not pregnant, doxycycline 100 mg PO bid × 4 wk or Tetracycline 500 mg PO qid × 4 wk |

| Tertiary syphilis | Penicillin G benzathine‡ 7.2 million U total, administered as 3 doses of 2.4 million U IM at 1-wk intervals If allergic to penicillin and not pregnant, same as for late latent syphilis |

|

| Neurosyphilis‖ | Aqueous crystalline penicillin G 200,000-300,000 U/kg/day q4-6hr × 10-14 days in doses not to exceed the adult dose | Aqueous crystalline penicillin G 18-24 million U/day administered as 3-4 million U IV q4hr × 10-14 days¶ or Penicillin G procaine,‡ 2.4 million U IM once daily plus probenecid 500 mg PO qid, both × 10-14 days¶ |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

* If the patient has no clinical manifestations of disease, the CSF examination is normal, and the CSF VDRL result is negative, some experts would treat with up to 3 weekly doses of penicillin G benzathine 50,000 U/kg IM. Some experts also suggest giving these patients a single dose of penicillin G benzathine 50,000 U/kg IM after the 10-day course of IV aqueous penicillin.

† Early latent syphilis is defined as being acquired within the preceding year.

‡ Penicillin G benzathine and penicillin G procaine are approved for IM administration only.

§ Late latent syphilis is defined as syphilis beyond 1 year’s duration.

‖ Patients who are allergic to penicillin should be desensitized.

¶ Some experts administer penicillin G benzathine 2.4 million U IM, once per week for up to 3 weeks after completion of these neurosyphilis treatment regimens.

From American Academy of Pediatrics: Red book: 2009 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, ed 28, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2009, American Academy of Pediatrics, p 647, Table 3.76.

Azimi PH, Janner D, Berne P, et al. Concentrations of procaine and aqueous penicillin in the cerebrospinal fluid of infants treated for congenital syphilis. J Pediatr. 1994;124:649-653.

Beck-Sague C, Alexander ER. Failure of benzathine penicillin G treatment in early congenital syphilis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6:1061-1064.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Congenital syphilis—United States, 2003–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:413-416.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis outbreak among American Indians—Arizona, 2007–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:158-161.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Primary and secondary syphilis—Jefferson county, Alabama, 2002–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;58:463-467.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis testing algorithms using treponemal tests for initial screening—four laboratories, New York City, 2005–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:872-875.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance reports, 2007 (website). www.cdc.gov/std/stats07/. Accessed August 25, 2010

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Primary and secondary syphilis—United States, 2003–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:269-272.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94. Erratum in MMWR Recomm Rep 15:55:997, 2006

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis physician pocket guide (PDF). www.cdc.gov/std/see/healthcareProviders/docpocket.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2010

Chakraborty R, Luck S. Managing congenital syphilis again? The more things change …. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:247-252.

Douglas JMJr. Penicillin treatment of syphilis: clearing away the shadow on the land. JAMA. 2009;301:769-771.

French P. Syphilis. BMJ. 2007;334:143-147.

Gottlieb SL, Pope V, Sternberg MR, et al. Prevalence of syphilis seroreactivity in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2001–2004. Sex Trans Dis. 2008;35:507-511.

Hall CS, Klausner JD, Bolan GA. Managing syphilis in the HIV-infected patient. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2004;6:72-81.

Hook EWII, Peeling RW. Syphilis control—a continuing challenge. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:122-124.

Mabey D, Peeling RW, Ballard R, et al. Prospective, multi-centre clinic-based evaluation of four rapid diagnostic tests for syphilis. Sex Trans Infect. 2006;82(Suppl 5):v13-v16.

Moyer VA, Schneider V, Yetman R, et al. Contribution of long-bone radiographs to the management of congenital syphilis in the newborn infant. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:353-357.

Peeling RW, Holmes KK, Mabey D, Ronald A. Rapid tests for sexually transmitted infections (STIs): the way forward. Sex Trans Infect. 2006;82(Suppl 5):v1-v16.

Peeling RW, Ye H. Diagnostic tools for preventing and managing maternal and congenital syphilis: an overview. Bull WHO. 2004;82:439-446.

Riedner G, Rusizoka M, Todd J, et al. Single-dose azithromycin versus penicillin G benzathine for the treatment of early syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1236-1244.

Seña AC, White BL, Sparling PF. Novel Treponema pallidum serologic tests: a paradigm shift in syphilis screening for the 21st century. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:700-708.

Tietz A, Davies SC, Moran JS. Guide to sexually transmitted disease resources on the Internet. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1304-1310.

Trepka MJ, Bloom SA, Zhang G, et al. Inadequate syphilis screening among women with prenatal care in a community with a high syphilis incidence. Sex Trans Dis. 2006;33:670-674.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for syphilis infection in pregnancy: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:705-709.

Wicher K, Horowitz HW, Wicher V. Laboratory methods of diagnosis of syphilis for the beginning of the third millennium. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1035-1049.

Woods CR. Syphilis in children: congenital and acquired. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2005;16:245-257.