Chapter 62B Surgery of the pancreas

Minimally invasive approaches

Diagnostic Laparoscopy

Diagnostic laparoscopy is a procedure that allows the surgeon to examine directly the contents of a patient’s abdomen or pelvis, including the peritoneum, small bowel, large bowel, liver, pancreas, or gallbladder (see Chapter 21). Pancreatic cancer is characterized by an aggressive, infiltrating local tumor growth and early manifestation of metastasis. Consequently, resection with curative intent can be performed in only 10% to 20% of patients with newly diagnosed pancreatic cancer.

Although staging of pancreatic cancer is critical to the planning of therapy and has improved over the past decades, especially as a result of better imaging techniques, there are still some patients in whom liver or peritoneal metastases are not detected during preoperative testing. Even with modern thin-sliced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), detecting hepatic or peritoneal metastases smaller than 5 mm is difficult and often impossible. Likewise, assessing local tumor extent and the degree of infiltration into adjacent organs remains challenging. In these cases, diagnostic laparoscopy is useful for assessing whether the patient is a candidate for curative resection or radiotherapy. In addition to the possibility of obtaining peritoneal fluid for cytology, following instillation of saline into the peritoneal cavity, laparoscopic ultrasonography (US) can be performed. This technique enables the detection of locally advanced disease and intraparenchymal liver involvement and gives a good indication of vascular involvement (Menack et al, 2001). Consequently, in many cases a primarily planned surgical pancreatic resection can be aborted with minimal surgical trauma. At the same time, tissue samples for histologic evaluation can be achieved from distant metastases and from large tumors, particularly when the body or tail of the pancreas is involved.

Overall, the indications for a staging laparoscopy in pancreatic cancer are 1) large primary lesions in the neck, body, or tail of the pancreas; 2) radiographic findings suggestive of occult metastases or a possible carcinomatosis; 3) small, hypodense regions in the hepatic parenchyma suspicious for liver metastases; and 4) subtle clinical and laboratory findings suggesting more advanced disease (Pisters et al, 2001). In eliminating nontherapeutic laparotomy and redirecting treatment plans, laparoscopy contributes significantly both to the proper management of patients with pancreatic cancer and to increased efficiency of resource utilization (Warshaw et al, 1986).

history of Laparoscopic Pancreatic Surgery (See Chapter 62A)

The slow progress of laparoscopy in pancreatic surgery in the past has been attributed to the retroperitoneal location of the gland, its proximity to various important vascular structures and organs, the friable nature of the gland, and the difficulty in its exposure. Similar to experiences with sigmoid colon resections, which were first performed in benign diseases such as recurrent sigma diverticulitis, laparoscopic pancreatic resections were initially performed for benign tumors. In particular, benign endocrine tumors less than 1 cm (e.g., insulinomas) or small cystadenomas predominantly located in the distal body and tail of the pancreas were ideally suited for the laparoscopic approach. In such cases, the surgical specimen is relatively small and contrasts greatly with the size of the abdominal incision required to access this retroperitoneal gland at conventional open surgery. Furthermore, enucleation or atypical resection can often be performed to remove small pancreatic lesions without the need for an anastomosis (Ammori, 2003).

Currently, laparoscopic resection can be performed both for benign and malignant pancreatic diseases. For benign tumors, left resections or enucleations can be often performed without difficulty. On the other hand, resections that require an anastomosis or those for malignant tumors that require an adequate margin and associated lymph node dissection remain tremendously challenging. Because lymphadenectomy in pancreatic cancer is technically difficult, especially along the celiac trunk and the superior mesenteric artery, few surgeons perform laparoscopic resections for malignant disease on a routine basis. Although many reports have demonstrated technical feasibility, it must be stated that not everything that can be done should be done. Sophisticated pancreatic resections such as pancreatoduodenectomy are only performed in highly select cases by exceptionally skilled laparoscopic surgeons to achieve a satisfying postoperative outcome (Gagner & Palermo, 2009). Because the challenge in pancreatic surgery for malignant disease is to achieve an R0 resection, even in advanced cases requiring vascular and/or multivisceral resections, we feel that the potential benefit of laparoscopic resections does not outweigh the risk in patients with cancer.

Laparoscopic Pancreatic Resections

Pancreatic Left Resection

Surgical Technique

Distal pancreatic resection has been performed for the treatment of patients with chronic pancreatitis and benign and malignant tumors in the tail or body of the pancreas. Initially, distal pancreatectomy was performed en bloc with the resection of the spleen. This technique was preferred by surgeons for technical as well as oncologic reasons. Because resection of the spleen has been reported to impair the immune system and could predispose to infective complications after distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy (Holdsworth et al, 1991), Kimura and colleagues (1996) developed a technique of preserving both the splenic artery and vein. In addition, Warshaw (1988) described a technique of distal pancreatectomy in which splenic vessels are ligated both at the level of transection of the pancreas and again at the splenic hilum, leaving the spleen to survive on blood flow through the short gastric vessels.

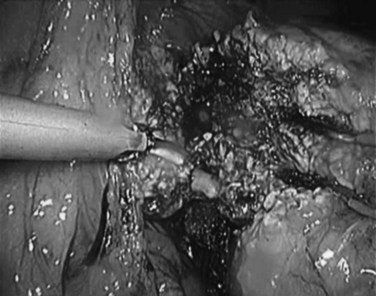

Over the past few years, the technique of laparoscopic pancreatic left resection has been introduced and refined. Many different methods have been described for trocar placement and surgical technique. In the technique used in Heidelberg, the patient is placed in a half-lateral position with the left side up. The surgeons stand on the right side of the patient, and the camera operator and scrub nurse stand on the opposite side. Four 10- to 12-mm trocars are inserted in the abdominal wall 3 to 4 cm above the umbilicus on the xiphoid area, subcostal on the midaxillary line, and subcostal to the midclavicular line. The first step is dissection of the splenorenal ligament; the splenic flexure of the colon is then mobilized downward. The gastrocolic omentum is widely opened along the gastroepiploic arcade up to the level of the mesenteric vessels, and the body and tail of the pancreas are then visualized (Fig. 62B.1). The inferior border of the pancreas is dissected, and the body and tail of the pancreas are completely detached from the retroperitoneum (Fig. 62B.2). This mobilization of the left pancreas allows visualization of the posterior wall of the gland, where the splenic vein is easily identified (Fig. 62B.3). The splenic vein is pushed away from the posterior pancreatic wall by gentle blunt dissection, and a tunnel is created between the splenic vein and the pancreas. The splenic artery is identified through this space by using careful blunt dissection with a curved dissector. Alternatively, the artery can be identified at the superior margin of the pancreas (Fig. 62B.4).

FIGURE 62B.1 Division of the gastrocolic ligament and entry into the lesser sac allows visualization of the body of the pancreas.

(Courtesy Dr. Bryce Gayet.)

FIGURE 62B.2 Mobilization of the inferior border of the pancreas in preparation for identification of the splenic vessels.

(Courtesy Dr. Bryce Gayet.)

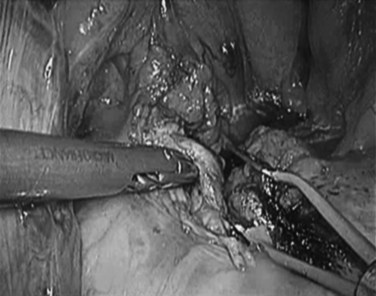

FIGURE 62B.3 Dissection of the splenic vein. In this view, the pancreas has already been divided.

(Courtesy Dr. Bryce Gayet.)

FIGURE 62B.4 The splenic artery is identified above the pancreas and is dissected in preparation for division.

(Courtesy Dr. Bryce Gayet.)

Next, the tail of the pancreas is grasped and retracted anteriorly. Traction is applied to expose the small branches of the splenic artery and vein, which are coagulated with the LigaSure device (Covidien, Mansfield, MA). The vascular area connecting the end of the tail of the pancreas and the spleen is transected. The left pancreas is then lifted up and mobilized posteriorly with the splenic artery and vein, which are clipped and divided or transected with an Endo-GIA stapler (Covidien) as they emerge from the pancreatic tail to enter the hilum of the spleen (Fernandez-Cruz, 2006). At the end, the pancreas is transected with an endoscopic linear stapler when the pancreas is soft and not too thick. Alternatively, the pancreas may be cut with scissors or with a LigaSure, with a separate suture applied directly to pancreatic duct.

Outcome of Laparoscopic Pancreatic Left Resection

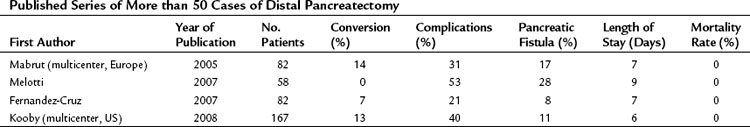

It has been convincingly shown that laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy is feasible with short- and long-term outcomes similar to open distal pancreatectomy (Kooby et al, 2010). Table 62B.1 gives an overview of recent series of more than 50 laparoscopic left pancreatic resections. In experienced hands, the laparoscopic approach has been associated with shorter operating times, early return of bowel function, minimal narcotic requirements, and early resumption of normal activities (Fernandez-Cruz et al, 2002). Sufficient experience and data confirm that laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy can be recommended as the treatment of choice for benign and noninvasive lesions in experienced hands when clinically indicated (Rosok et al, 2010); however, it is difficult to make a clear statement concerning malignant pancreatic tumors because of the lack of conclusive data (Merchant et al, 2009). An important problem leading to conversion in many studies has been the difficulty in localizing small tumors by laparoscopy or laparoscopic US.

Tumor Enucleation

Surgery is the only potentially curative treatment for pancreatic endocrine tumors amenable to resection. With the exception of gastrinomas and somatostatinomas, which are frequently localized in the head of the pancreas, neuroendocrine tumors are located predominantly in the body and tail of the pancreas. This location makes these tumors suitable for a laparoscopic surgical approach. In many cases, especially in sporadic insulinomas and if tumor size does not exceed 2 cm, laparoscopic enucleation can be performed safely (Bozbora et al, 2004). Other functioning and nonfunctioning neuroendocrine tumors should be managed with extended pancreatic resection, including peripancreatic lymph node dissection, because the malignant potential must be considered. In preoperative examination, a combination of dynamic CT and selected angiography leads to a correct diagnosis in 70% to 90% of patients (Cuschieri et al, 1996). Tumors located in the pancreatic body and tail, distant from the splenic vessels and the main pancreatic duct, are good candidates for laparoscopic enucleation if no findings of malignancy are detected on preoperative staging (Tihanyi et al, 1997).

Surgical Technique

The position of the patient and the trocar sites are the same as for distal pancreatectomy. Intraoperative US is required to confirm the location of the tumor and the absence of other lesions. If the tumor is located close to the splenic vessels, the main pancreatic duct, or the bile duct, enucleation should be abandoned in favor of a formal resection (Kano et al, 2002). For dissection of the tumor from the pancreatic parenchyma, some surgeons prefer the use of a Harmonic Scalpel (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) or Ligasure. Because enucleations have a high risk of postoperative fistula, mainly type A fistula, a drain should be placed adjacent to the side of the enucleation.

Pancreatoduodenectomy (See Chapter 62A)

Although the first successful pancreatoduodenectomies were performed in 1912 and 1934 by Walter Kausch and Allan Whipple, respectively, the first attempt at laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy (PPPD) has been credited to Gagner and Pomp (1994). Today, a number of laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomies or Whipple procedures have been performed in different centers with reasonable outcomes; therefore, no doubt remains that the Whipple procedure can be performed by laparoscopy.

Surgical Technique

A positive correlation has been shown between postoperative mortality and morbidity and the experience of a surgeon and volume of a center (Birkmeyer et al, 2002). This is probably also true for the laparoscopic pancreatic resection; however, larger series that investigate this relationship have yet to be undertaken.

Outcome of Laparoscopic Pancreatoduodenectomy

The first laparoscopic PPPD was performed in 1992 and took at least 10 hours, even for a highly skilled endoscopic surgeon (Gagner & Pomp, 1994). The patient’s postoperative course was complicated by delayed gastric emptying, resulting in a 30-day hospitalization. Cuschieri (1994) also reported two cases of PPPD with disappointing postoperative outcomes, including pancreatic fistula and delayed gastric emptying. Nevertheless, several centers with expert surgeons continued to perform this complicated procedure, and between 1994 and 2008, a total of 146 laparoscopic Whipple procedures were reported in scientific literature.

Reviewing the existing literature, Gagner and Palermo (2009) have shown that this complex surgical procedure can be performed laparoscopically with acceptable complication rates in selected patients. In the series described, the mean operating time was 439 minutes, average blood loss was 143 mL, and median hospital stay was 18 days. Postoperative complications included 2 hemorrhages, 4 bowel obstructions, 1 stress ulcer, 1 delay of gastric emptying, 4 pneumonias, and 11 leaks. Although laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy and laparoscopic duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection are technically feasible, laparoscopic reconstruction after proximal pancreatectomy is not yet generally practiced because performance is limited to highly skilled endoscopic surgeons. To justify the performance of laparoscopic proximal pancreatectomy, it is mandatory to demonstrate the potential clinical benefits and safety of such a complicated procedure (Takaori & Tanigawa, 2007). Furthermore, in patients with pancreatic cancer, it yet has to be validated whether radical lymph node dissection is feasible in the same manner and extent as open surgery.

Laparoscopic Palliative Procedures For Pancreatic Cancer (See Chapter 63B)

Currently, endoscopic biliary stenting is the most widely performed procedure for palliation in patients with malignant biliary obstruction as a result of pancreatic cancer. However, patients with endobiliary prostheses who survive for a long time have a significant risk of stent obstruction. In patients expected to have a prolonged survival, laparoscopic biliary decompression can be performed and is a reasonable consideration. The main types of surgical palliation of malignant biliary obstruction are choledochoenterostomy and cholecystoenterostomy. With regard to outcomes and complications, choledochoenterostomy has been shown to be better than cholecystoenterostomy (Sarfeh et al, 1988). Although both procedures have been described to be feasible laparoscopically, the cholecystoenterostomy is technically easier to perform (Sussman et al, 1996). Nevertheless, because cholecystoenterostomy would never be used in conventional open surgery, this compromise should not be accepted in laparoscopic surgery either, and an inferior operation should not be performed only because it is easier.

In patients with locally advanced and inoperable pancreatic cancer, whether associated with gastric outlet obstruction or not, a retrocolic gastrojejunostomy should be added to a biliary bypass. Today, gastroenterostomy can be performed laparoscopically with acceptable outcomes (Rhodes et al, 1995). Where it is not feasible or meaningful to perform a gastroenterostomy because of extensive peritoneal disease, particularly that involving the bowel in the lower abdomen, a palliative stoma must be considered to ensure gastrointestinal patency. It has been reported that a palliative stoma done laparoscopically has significantly better outcomes in terms of postoperative morbidity and mortality compared with the open surgical procedure (Scheidbach et al, 2009). However, laparoscopic palliation of locally advanced pancreatic cancer always demands a high level of technical expertise and should be limited to performance by experts in specialized centers (Gentileschi et al, 2002).

Robotic Approaches for Pancreatic Resections

Recently, it has been reported that laparoscopic pancreatic surgery can be performed with robotic assistance. A single-center study analyzed the charts of 134 patients who underwent robotic-assisted surgery for different pancreatic pathologies with the DaVinci system (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA) (Giulianotti et al, 2010). The authors showed that complication and mortality rates were comparable to those of open surgery but with the advantages of minimally invasive surgery. In another series of 17 robotic-assisted distal pancreatectomies, a shorter length of stay in robotic versus laparoscopic or open approaches has been reported. Furthermore, in this study, spleen preservation rates improved with a robotic approach at the expense of increased operative time. The authors conclude that robotic distal pancreatectomy is safe and cost effective in selected cases (Waters et al, 2010), although the indication for robotic surgery in pancreatic disease has been controversial, particularly considering the cost of robotic procedures compared with laparoscopic resection. Further experience and randomized clinical trials are clearly needed to evaluate the benefit of this surgical approach. In addition, the cost-benefit comparison needs to be assessed for this expensive method.

Ammori BJ. Pancreatic surgery in the laparoscopic era. JOP. 2003;4(6):187-192.

Birkmeyer JD, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(15):1128-1137.

Bozbora A, et al. Is laparoscopic enucleation the gold standard in selected cases with insulinoma? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2004;14(4):230-233.

Cuschieri A. Laparoscopic surgery of the pancreas. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1994;39(3):178-184.

Cuschieri A, Jakimowicz JJ, van Spreeuwel J. Laparoscopic distal 70% pancreatectomy and splenectomy for chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1996;223(3):280-285.

Fernandez-Cruz L. Distal pancreatic resection: technical differences between open and laparoscopic approaches. HPB (Oxford). 2006;8(1):49-56.

Fernandez-Cruz L, et al. Outcome of laparoscopic pancreatic surgery: endocrine and nonendocrine tumors. World J Surg. 2002;26(8):1057-1065.

Gagner M, Palermo M. Laparoscopic Whipple procedure: review of the literature. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16(6):726-730.

Gagner M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc. 1994;8(5):408-410.

Gentileschi P, Kini S, Gagner M. Palliative laparoscopic hepatico- and gastrojejunostomy for advanced pancreatic cancer. JSLS. 2002;6(4):331-338.

Giulianotti PC, et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic pancreatic surgery: single-surgeon experience. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(7):1646-1657.

Holdsworth RJ, Irving AD, Cuschieri A. Postsplenectomy sepsis and its mortality rate: actual versus perceived risks. Br J Surg. 1991;78(9):1031-1038.

Kano N, et al. Laparoscopic pancreatic surgery: its indications and techniques: from the viewpoint of limiting the indications. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9(5):555-558.

Kimura W, et al. Spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy with conservation of the splenic artery and vein. Surgery. 1996;120(5):885-890.

Kooby DA, et al. A multicenter analysis of distal pancreatectomy for adenocarcinoma: is laparoscopic resection appropriate? J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(5):779-785. 786-777

Menack MJ, Spitz JD, Arregui ME. Staging of pancreatic and ampullary cancers for resectability using laparoscopy with laparoscopic ultrasound. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(10):1129-1134.

Merchant NB, Parikh AA, Kooby DA. Should all distal pancreatectomies be performed laparoscopically? Adv Surg. 2009;43:283-300.

Pisters PW, et al. Laparoscopy in the staging of pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88(3):325-337.

Rhodes M, Nathanson L, Fielding G. Laparoscopic biliary and gastric bypass: a useful adjunct in the treatment of carcinoma of the pancreas. Gut. 1995;36(5):778-780.

Rosok BI, et al. Single-centre experience of laparoscopic pancreatic surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97(6):902-909.

Sarfeh IJ, et al. A prospective, randomized clinical investigation of cholecystoenterostomy and choledochoenterostomy. Am J Surg. 1988;155(3):411-414.

Scheidbach H, et al. Palliative stoma creation: comparison of laparoscopic vs conventional procedures. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394(2):371-374.

Sussman LA, Christie R, Whittle DE. Laparoscopic excision of distal pancreas including insulinoma. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66(6):414-416.

Takaori K, Tanigawa N. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: the past, present, and future. Surg Today. 2007;37(7):535-545.

Tihanyi TF, et al. Laparoscopic distal resection of the pancreas with the preservation of the spleen. Acta Chir Hung. 1997;36(1-4):359-361.

Traverso LW, Longmire WP. Preservation of the pylorus in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Gyn Obstet. 1978;146:959-962.

Warshaw AL, Tepper JE, Shipley WU. Laparoscopy in the staging and planning of therapy for pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg. 1986;151(1):76-80.

Warshaw AL. Conservation of the spleen with distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 1988;123(5):550-553.

Waters JA, et al. Robotic distal pancreatectomy: cost effective? Surgery. 2010;148(4):814-823.