32 Supraorbital Nerve Block for Supraorbital Neuralgia

Anatomy

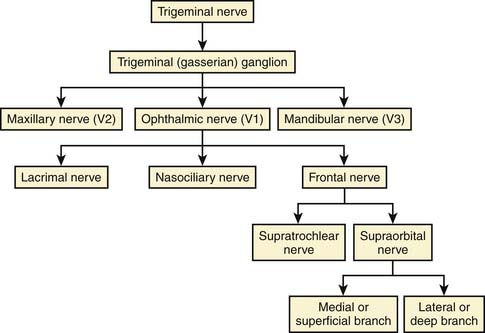

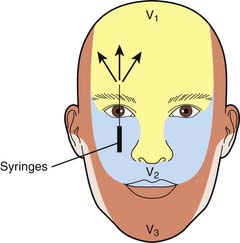

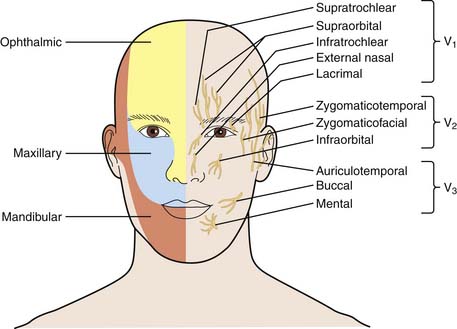

The supraorbital nerve (SON) is purely a general sensory (afferent) nerve. The supraorbital nerve is a continuation of the frontal nerve, which is one of the three main branches of the ophthalmic division (V1) of the trigeminal nerve (the fifth cranial nerve) (Figs. 32-1 and 32-2).

Figure 32-1 Nerve supply for the face (right) and the sensory distribution of the trigeminal nerve (left).

(Adapted from NYSORA.com.)

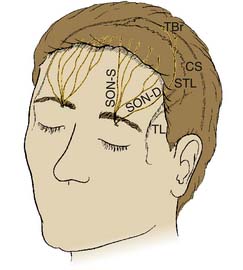

The supraorbital nerve exits from the supraorbital foramen or notch along the superior rim of the frontal bone, accompanied by the supraorbital artery. In the supraorbital notch, the supraorbital nerve gives off small filaments that supply the mucosal membrane of the frontal sinus and filaments that supply the upper eyelid. The supraorbital nerve is usually located 2.7 cm from the midline (Fig. 32-3).1,2

The supraorbital nerve course beyond the supraorbital notch has only recently been explored due to advancement in plastic surgical techniques. The detailed anatomic course and its innervations is studied in fresh cadaver specimens and its sensory distribution in living subjects using selective nerve block. SON divides to two branches above the orbital rim, the superficial and deep branches. The medial (superficial) division passes over the frontalis muscle and divides into multiple smaller branches with cephalic distribution toward the hairline. It provides sensory innervations to the forehead skin and anterior scalp as far as the vertex. The deep (lateral) division runs deep in the frontalis across the lateral forehead between the galea aponeurotica and the pericranium. The deep division supplies sensory innervation to underlying periosteum and frontal parietal scalp.3,4

The supratrochlear nerve (STN) is a branch of the frontal nerve and supplies sensory innervations to the bridge of the nose, medial part of the upper eyelid, and medial forehead. The supratrochlear nerve is usually located 1.7 cm from the midline.1,4

Indications

Supraorbital nerve blockade has been used routinely alone or in combination with occipital nerve block in a variety of cosmetic, ophthalmologic, and cranial procedures.5 It can be used in chronic pain states that are related to postherpetic neuralgia and supraorbital neuropathy or neuralgias as adjuvant therapy along with pharmacologic treatment or alone. There are several potential sites for supraorbital nerve entrapment, such as a fibrous band at the supraorbital notch and/or compression of the nerve as it travels through muscles or fascia. Supraorbital nerve block has also been used to control pain in intractable headaches. Although the effect of each block is limited in duration, a series of injections appears to provide sustained relief. However, no controlled studies have indicated blocks as a tenable intervention.6

Technique for Nerve Block

This diagnostic technique blocks the medial and lateral branches of SON, which supply the forehead and scalp. Insert a 25-gauge 1½ inch needle through the skin about 2 cm above the eyebrow and 2.2 cm from midline. The needle is advanced about 1 inch laterally to 10 o’clock to block the deep (lateral branch) with 1 mL of 1% lidocaine. Then withdraw the needle to insertion point and redirect medially to 12 and 2 o’clock to block the superficial (medial) branch with 1 mL of 1% lidocaine after negative aspiration. There may be resistance during the injection if the needle is located in fascia. This can be avoided by advancing the needle at its entire length and injecting while withdrawing the needle to insertion point. A “fan” technique is recommended to block supraorbital dermatome because of individual variation in the anatomy.7,8

The patient will report numbness of the forehead and vertex in a few minutes if the block is successful. If a diagnostic block is positive and patient reports numbness and relief of pain symptoms in the supraorbital nerve distribution, then subsequent block can proceed with corticosteroid injection of 10 to 20 mg of triamcinolone or methylprednisolone, or these can be mixed with the local anesthetic at the time of the block to a 50:50 mixture with local anesthetic with the goal of approximately 1 mL of volume delivered to each of the lateral and medial branches of the supraorbital nerve (Fig. 32-4).

Other Treatments for Supraorbital Neuralgia

Lidocaine in the form of topical 5% or as a patch has been used for control of postherpetic neuralgia, and may be helpful for supraorbital neuralgia.9 Capsaicin was effective in trials of patients with severe refractory postherpetic neuralgia, however, topical capsaicin products have the risk of eye infiltration and eye damage.10

Oral pharmacologic treatments, tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, oxycodone, tramadol, dextromethorphan, memantine, mexiletine, and newer drugs such as duloxetine and pregabalin have a role in treatment of postherpetic neuralgia and entrapment neuropathies involving the supraorbital nerve.11–14 Side effects are a limiting factor, especially in the geriatric population and in oncology patients.

Surgical resection of forehead muscles as the glabella and procerus has been used for control of headaches and may have a role.15 Peripheral nerve stimulation was also shown to be effective in limited case reports.16

1. Williams P.L., Warwick R., Dyson M., Bannister L.H., editors. Gray’s Anatomy, 37th ed. London: Churchill Livingstone. 1989:1100.

2. Ramirez OM, Robertson KM. Update in endoscopic forehead rejuvenation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2002;10(1):37–51.

3. Knize D.M. A study of the supraorbital nerve. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:564-569.

4. Janis J.E., Ghavami A., Lemmon J.A., et al. The anatomy of the corrugator supercilii muscle: Part II. Supraorbital nerve branching patterns. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(1):233-240.

5. Nguyen A., Girard D., Boudreault D., et al. Scalp nerve blocks decrease the severity of pain after craniotomy. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:1272-1276.

6. Bogduk N. Role of anesthesiologic blockade in headache management. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2004;8(5):399-403.

7. Beer G., Putz R., Mager K., et al. Variations of the frontal exit of the supraorbital nerve: An anatomic study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:334-341.

8. Cheng A., Yuen H., Lucas P.W., et al. Characterization and localization of the supraorbital and frontal exits of the supraorbital nerve in Chinese: An anatomic study. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22(3):209-213.

9. Galer B.S., Rowbotham M.C., Perander J., Friedman E. Topical lidocaine patch relieves postherpetic neuralgia more effectively than a vehicle topical patch: Results of an enriched enrollment study. Pain. 1999;80:533-538.

10. Watson C.P., Tyler K.L., Bickers D.R., et al. A randomized vehicle-controlled trial of topical capsaicin in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. Clin Ther. 1993;15:510-526.

11. Christo P.J., Hobelman G., Maine D.N. Post-herpetic neuralgia in older adults: Evidence-based approaches to clinical management. Drugs Aging. 2007;24(1):1-19.

12. Alper B.S., Lewis P.R. Treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: A systematic review of the literature. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(2):121-128.

13. Dworkin R.H., Corbin A.E., Young J.P.Jr., et al. Pregabalin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2003. 22:60(8):1274–1283

14. Lewith G.T., Field J., Machin D. Acupuncture compared with placebo in postherpetic pain. Pain. 1983;17:361-368.

15. Caputi C.A. Firetto V: Therapeutic blockade of greater occipital and supraorbital nerves in migraine patients. Headache. 1997;37(3):174-179.

16. Amin S., Buvanendran A., Park K.S., et al. Peripheral nerve stimulator for the treatment of supraorbital neuralgia: A retrospective case series. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(4):355-359.