Chapter 220 Spotted Fever and Transitional Group Rickettsioses

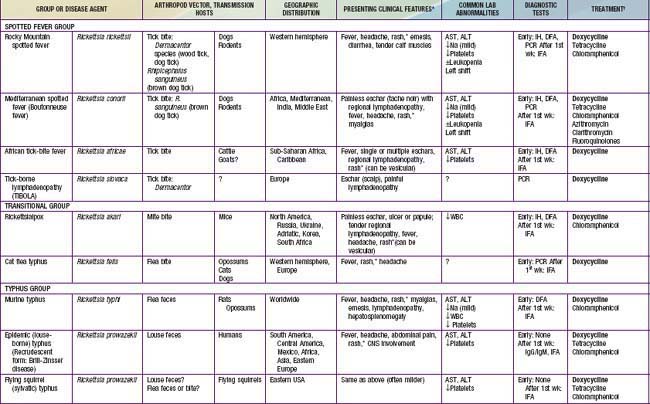

Rickettsia species were classically divided into “spotted fever” and “typhus” groups based on serologic reactions. The outer membrane protein A (ompA) gene is present in spotted fever but not typhus group organisms. Complete genome sequences have further refined distinctions, and several species that possess ompA, but are genetically distinct from others in the spotted fever group, have been reassigned to a “transitional” group. Many members of the spotted fever group of rickettsiae are pathogenic for humans (Table 220-1). These include the tick-borne agents Rickettsia rickettsii, the cause of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF); R. conorii, the cause of Mediterranean spotted fever (MSF) or boutonneuse fever; R. sibirica, the cause of North Asian tick typhus; R. japonica, the cause of Oriental spotted fever; R. honei, the cause of Flinders Island spotted fever or Thai tick typhus; R. africae, the cause of African tick bite fever; and unnamed Israeli spotted fever rickettsia, and possibly others. Members of the transitional group include R. akari, the cause of mite-transmitted rickettsialpox; R. felis, the cause of cat flea–transmitted typhus; and R. australis, the cause of tick-transmitted Queensland tick typhus.

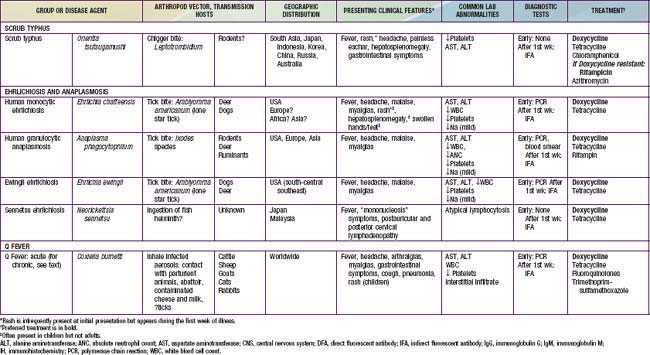

Table 220-1 SUMMARY OF RICKETTSIAL DISEASES OF HUMANS, INCLUDING RICKETTSIA, ORIENTIA, EHRLICHIA, ANAPLASMA, NEORICKETTSIA, AND COXIELLA

220.1 Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (Rickettsia rickettsii)

Megan E. Reller and J. Stephen Dumler

Transmission

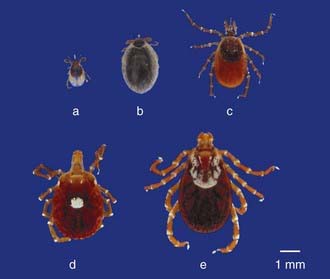

Ticks are the natural hosts, reservoirs, and vectors of R. rickettsii. Ticks maintain the infection in nature by transovarial transmission (passage of the organism from infected ticks to their progeny). Ticks harboring rickettsiae are substantially less fecund than uninfected ticks; thus, horizontal transmission (acquisition of rickettsiae by taking a blood meal from transiently rickettsemic animal hosts such as small mammals or dogs) significantly contributes to maintenance of rickettsial infections in ticks. Ticks transmit the infectious agent to mammalian hosts (including humans) via infected saliva during feeding. The pathogen R. rickettsii in ticks becomes virulent after exposure to blood or increased temperature; thus, the longer the tick is attached, the greater the risk of transmission. The principal tick hosts of R. rickettsii are Dermacentor variabilis (the American dog tick) in the eastern USA and Canada, Dermacentor andersoni (the wood tick) in the western USA and Canada, Rhipicephalus sanguineus (the common brown dog tick) in the southwestern USA and in Mexico, and Amblyomma cajennense in Central and South America (Fig. 220-1).

Clinical Manifestations

Rash usually appears only after 2-4 days of illness, and approximately 5% of children and up to 20% of adults never develop a rash that is recognized. Rash occurs more reliably in children than in adults. Initially, discrete, pale, rose-red blanching macules or maculopapules appear, characteristically on the extremities, including the ankles, wrists, or lower legs (Fig. 220-2). The rash then spreads rapidly to involve the entire body, including the soles and palms. After several days, the rash becomes more petechial or hemorrhagic, sometimes with palpable purpura. In severe disease, the petechiae can enlarge into ecchymosis, which can become necrotic. Severe vascular obstruction secondary to the rickettsial vasculitis and thrombosis is uncommon but can result in gangrene of the digits, earlobes, scrotum, nose, or an entire limb.

220.2 Mediterranean Spotted Fever or Boutonneuse Fever (Rickettsia conorii)

Megan E. Reller and J. Stephen Dumler

Etiology

MSF is caused by systemic endothelial cell infection by the obligate intracellular bacterium R. conorii. Similar species are distributed globally, such as R. sibirica in Russia, China, Mongolia, and Pakistan; R. australis and R. honei in Australia; R. japonica in Japan; and R. africae in South Africa (see Table 220-1). Analysis of antigens and related DNA sequences show that all are closely related to R. rickettsii, the cause of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF).

Billings AN, Rawlings JA, Walker DH. Tick-borne disease in Texas: a 10-year retrospective examination of cases. Tex Med. 1998;94:66-76.

Buckingham SC. Rocky Mountain spotted fever: a review for the pediatrician. Pediatr Ann. 2002;31:163-168.

Buckingham SC, Marshall GS, Schutze GE, et al. Clinical and laboratory features, hospital course, and outcome of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in children. J Pediatr. 2007;150:180-184.

Cascio A, Colomba C, Antinori S, et al. Clarithromycin versus azithromycin in the treatment of Mediterranean spotted fever in children: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:154-158.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Consequences of delayed diagnosis of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in children—West Virginia, Michigan, Tennessee, and Oklahoma, May-July 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:885-888.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnosis and management of tickborne rickettsial diseases: Rocky Mountain spotted fever, ehrlichioses, and anaplasmosis—United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-29.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fatal cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in family clusters—three states, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:407-410.

Comer JA, Tzianabos T, Flynn C, et al. Serologic evidence of rickettsialpox (Rickettsia akari) infection among intravenous drug users in inner-city Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:894-898.

Demma LJ, Traeger MS, Nicholson WL, et al. Rocky Mountain spotted fever from an unexpected tick vector in Arizona. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:587-594.

Dumler JS, Walker DH. Rocky Mountain spotted fever—changing ecology and persisting virulence. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:551-553.

Holman RC, Paddock CD, Curns AT, et al. Analysis of risk factors for fatal Rocky Mountain spotted fever: evidence for superiority of tetracyclines for therapy. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1437-1444.

Marshall GS, Stout GG, Jacobs RF, et al. Antibodies reactive to Rickettsia rickettsii among children living in the southeast and south central regions of the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:443-448.

Sexton DJ, Kaye KS. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:351-360.

Thorner AR, Walker DH, Petri WA. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:1353-1359.

Treadwell TA, Holman RC, Clarke MJ, et al. Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the United States, 1993–1996. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:21-26.

Walker DH. Tick-transmitted infectious diseases in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:237-269.