Spine

A Anatomy (see Chapter 2, Anatomy)

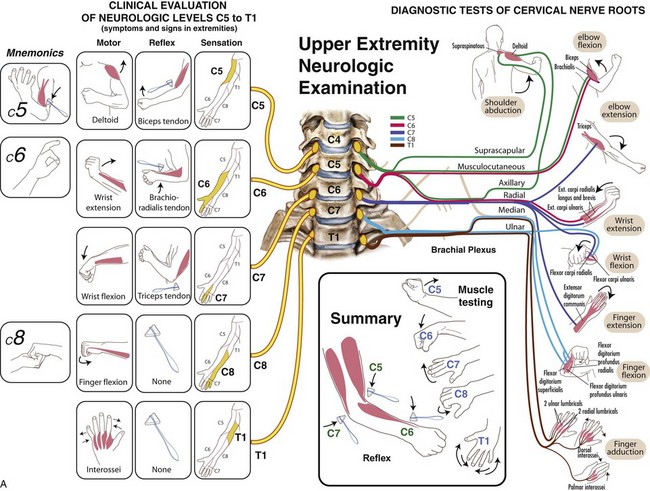

B History and physical examination (Table 8-1; Figure 8-1)

Table 8-1

Examination of Patients with Disorders of the Spine

| Component | Features |

| Inspection | Overall alignment in sagittal and coronal planes (sciatic scoliosis) |

| Gait | Wide-based (myelopathy), forward-leaning (stenosis), antalgic |

| Palpation | Localized posterior swelling (trauma), acute gibbus deformity, tenderness |

| Range of motion | Flexion/extension, lateral bend, full versus limited |

| Neurologic function | Motor, sensory, reflexes, assessment of long-tract signs (see also Table 8-7) |

| Special tests | Straight-leg raise, Spurling test, Waddell signs of inorganic pathology |

1. Localized pain (tumor, infection)

2. Mechanical pain (instability, discogenic disease)

3. Radicular pain (herniated nucleus pulposus [HNP], stenosis), night pain (tumor)

4. Systemic symptoms such as fever or unexplained weight loss (infection, tumor)

5. The physical examination must evaluate both the spine and the neurologic function of the extremities (Table 8-2).

6. Localized hip and shoulder pathology may simulate spine disease and must also be evaluated.

1. Plain radiographs should be obtained 4 to 6 weeks after onset of symptoms; add flexion-extension views for suspected instability.

2. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is excellent for further imaging of HNP, stenosis, soft tissue, tumor, and infection.

3. Computed tomography (CT) with fine cuts ± myelographic dye is used to examine bony anatomy after previous surgery and the quality of fusion.

4. Bone scan is helpful in evaluating metastatic disease and may be negative with multiple myeloma.

5. Laboratory evaluation consists of C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate for infection, metabolic screening, serum/urine protein electrophoresis for myeloma, and a complete blood cell count (there is often a high-normal white blood cell count with infection or anemia with myeloma).

D Workup of back pain—Complaint of back pain is second only to upper respiratory tract infection as a cause of office visits, with 60% to 80% lifetime prevalence. Standard workup begins with a history (most important) and progresses to physical examination (see Table 8-1). Radiographic and laboratory studies rarely help in acute cases. The following considerations in the evaluation of back pain are important:

Children may be affected by congenital or, more often, developmental disorders or infection.

Children may be affected by congenital or, more often, developmental disorders or infection.

Young adults are more likely to suffer from disc disease, spondylolisthesis, or acute fractures.

Young adults are more likely to suffer from disc disease, spondylolisthesis, or acute fractures.

Complaints from older adults, including spinal stenosis, metastatic disease, and osteopenic compression fractures are more common.

Complaints from older adults, including spinal stenosis, metastatic disease, and osteopenic compression fractures are more common.

2. Radicular signs and symptoms

Often associated with disc herniation or spinal stenosis

Often associated with disc herniation or spinal stenosis

Intraspinal pathologic conditions or other entities associated with cord or root impingement may be responsible.

Intraspinal pathologic conditions or other entities associated with cord or root impingement may be responsible.

Herpes zoster is a rare cause of lumbar radiculopathy, with pain preceding the skin eruption.

Herpes zoster is a rare cause of lumbar radiculopathy, with pain preceding the skin eruption.

3. Systemic symptoms—Careful history-taking can help guide diagnosis of systemic conditions with associated spine pathology.

Infection (confirmed by laboratory studies)

Infection (confirmed by laboratory studies)

Chronic back pain is often refractory to localized treatment in many patients with fibromyalgia.

Chronic back pain is often refractory to localized treatment in many patients with fibromyalgia.

4. Sources of referred back pain

5. Psychogenic pain—may play important role in some patients with chronic low back disorders

A Cervical spondylosis—Chronic disc degeneration and associated facet arthropathy result in three clinical entities:

Discogenic neck pain (axial pain)

Discogenic neck pain (axial pain)

Radiculopathy (root compromise)

Radiculopathy (root compromise)

Myelopathy (cord compression) and combinations of these conditions

Myelopathy (cord compression) and combinations of these conditions

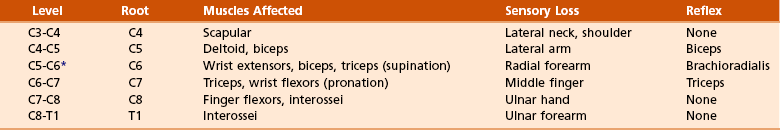

2. Pathoanatomy—Cervical spondylosis involves the intervertebral disc and four other articulations (Figure 8-2):

Two uncovertebral joints (of Luschka)

Two uncovertebral joints (of Luschka)

Two facet joints—Facet joint capsules are known to have sensory receptors that may play a role in pain and proprioceptive sensation in the cervical spine.

Two facet joints—Facet joint capsules are known to have sensory receptors that may play a role in pain and proprioceptive sensation in the cervical spine.

Cord compromise as canal diameter decreases

Cord compromise as canal diameter decreases

Progressive collapse of the cervical discs, resulting in loss of normal lordosis of the cervical spine and chronic anterior cord compression across the kyphotic spine/anterior chondroosseous spurs

Progressive collapse of the cervical discs, resulting in loss of normal lordosis of the cervical spine and chronic anterior cord compression across the kyphotic spine/anterior chondroosseous spurs

Spondylotic changes in the foramina, primarily from chondroosseous spurs of the joints of Luschka, may restrict motion and lead to nerve root compression.

Spondylotic changes in the foramina, primarily from chondroosseous spurs of the joints of Luschka, may restrict motion and lead to nerve root compression.

Usually posterolateral, between the posterior edge of the uncinate process and the lateral edge of the posterior longitudinal ligament, it may result in acute radiculopathy.

Usually posterolateral, between the posterior edge of the uncinate process and the lateral edge of the posterior longitudinal ligament, it may result in acute radiculopathy.

Anterior herniation may cause dysphagia (rare).

Anterior herniation may cause dysphagia (rare).

Myelopathy may be seen with large central herniation or spondylotic bars with a congenitally narrow canal.

Myelopathy may be seen with large central herniation or spondylotic bars with a congenitally narrow canal.

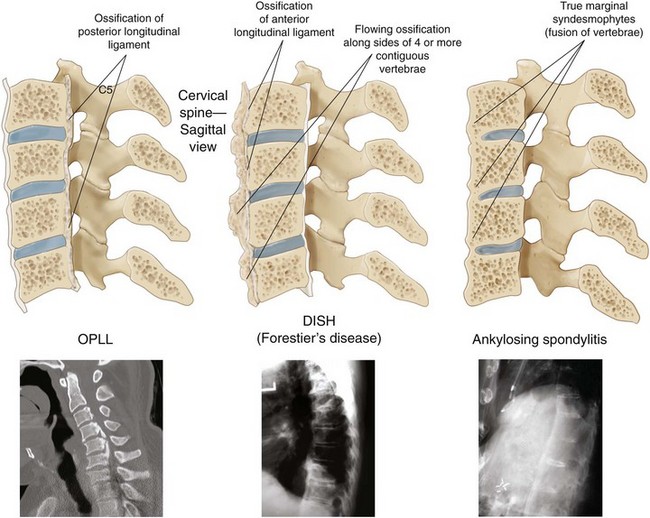

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament

Neck extension: Cord is compressed between the degenerative disc and spondylotic bar anteriorly and the hypertrophic facets and infolded ligamentum flavum posteriorly.

Neck extension: Cord is compressed between the degenerative disc and spondylotic bar anteriorly and the hypertrophic facets and infolded ligamentum flavum posteriorly.

Neck flexion results in slight increase in canal diameter and relief of cord compression.

Neck flexion results in slight increase in canal diameter and relief of cord compression.

3. Signs and symptoms—Degenerative discogenic neck pain may present as the insidious onset of neck pain without neurologic signs or symptoms, exacerbated by excess vertebral motion.

Can involve one or multiple roots

Can involve one or multiple roots

Neck, shoulder, and arm pain; paresthesias; and numbness

Neck, shoulder, and arm pain; paresthesias; and numbness

Overlapping findings because of intraneural intersegmental connections of sensory nerve roots

Overlapping findings because of intraneural intersegmental connections of sensory nerve roots

Symptoms are exacerbated by mechanical stress such as excessive vertebral motion, in particular rotation and lateral bend with a vertical compressive force (Spurling test).

Symptoms are exacerbated by mechanical stress such as excessive vertebral motion, in particular rotation and lateral bend with a vertical compressive force (Spurling test).

Relief of radicular pain with shoulder abduction is suggestive of a cervical etiology.

Relief of radicular pain with shoulder abduction is suggestive of a cervical etiology.

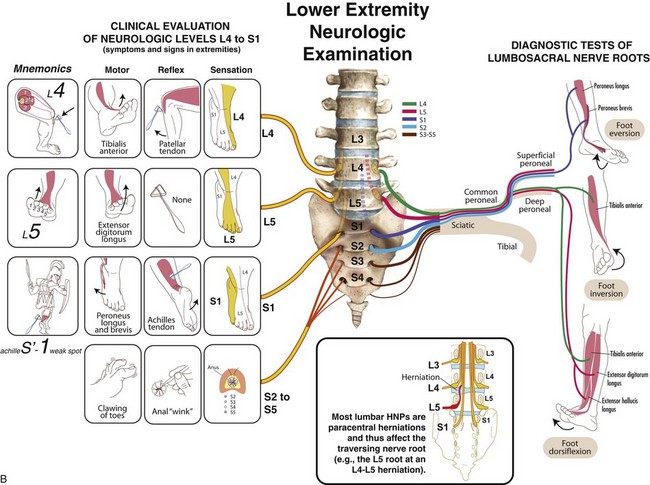

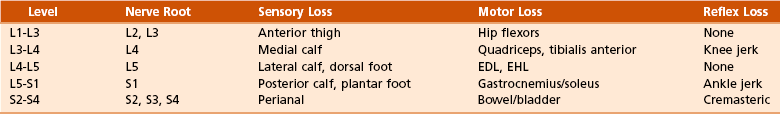

Caudal nerve root at a given level is usually affected (see Table 8-2).

Caudal nerve root at a given level is usually affected (see Table 8-2).

4. Physical examination findings

Upper motor neuron findings in myelopathy

Upper motor neuron findings in myelopathy

“Myelopathy hand” and the “finger escape sign” (small finger spontaneously abducts because of weak intrinsic muscles)

“Myelopathy hand” and the “finger escape sign” (small finger spontaneously abducts because of weak intrinsic muscles)

Inverted radial reflex (ipsilateral finger flexion when eliciting the brachioradialis reflex)

Inverted radial reflex (ipsilateral finger flexion when eliciting the brachioradialis reflex)

Upper extremities may have radicular (lower motor neuron) signs along with evidence of distal myelopathy.

Upper extremities may have radicular (lower motor neuron) signs along with evidence of distal myelopathy.

Upper motor neuron findings are not always present in all patients.

Upper motor neuron findings are not always present in all patients.

Funicular pain—central burning and stinging with or without the Lhermitte sign (radiating lightning-like sensations down the back with neck flexion)

Funicular pain—central burning and stinging with or without the Lhermitte sign (radiating lightning-like sensations down the back with neck flexion)

Effectively demonstrates neural compressive pathology

Effectively demonstrates neural compressive pathology

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Extraforaminal cervical nerve blocks

Extraforaminal cervical nerve blocks

Temporary collar immobilization

Temporary collar immobilization

Pain clinic modalities are helpful in most cases of discogenic neck pain and radiculopathy

Pain clinic modalities are helpful in most cases of discogenic neck pain and radiculopathy

Extraforaminal nerve blocks have been shown to be safe in large series of patients, with a less than 2% rate of minor complications

Extraforaminal nerve blocks have been shown to be safe in large series of patients, with a less than 2% rate of minor complications

Combined anterior (cervical) Smith-Robinson discectomy and fusion (ACDF)

Combined anterior (cervical) Smith-Robinson discectomy and fusion (ACDF)

Involves excision of osteophytes and corpectomy with a strut graft fusion with or without instrumentation

Involves excision of osteophytes and corpectomy with a strut graft fusion with or without instrumentation

Anterior plating may increase the fusion rate in multilevel discectomies with fusion and will protect a strut graft in multilevel corpectomies.

Anterior plating may increase the fusion rate in multilevel discectomies with fusion and will protect a strut graft in multilevel corpectomies.

Adjunctive posterior plating may be considered in cases involving prior laminectomy, multilevel corpectomy and strut grafting, or three-level ACDF.

Adjunctive posterior plating may be considered in cases involving prior laminectomy, multilevel corpectomy and strut grafting, or three-level ACDF.

Used for multilevel spondylosis and myelopathy and ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL)

Used for multilevel spondylosis and myelopathy and ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL)

Allows for more extensive decompression

Allows for more extensive decompression

Lower incidence of instability compared with multilevel laminectomies

Lower incidence of instability compared with multilevel laminectomies

Contraindicated in setting of fixed kyphosis

Contraindicated in setting of fixed kyphosis

1. Congenital versus acquired (traumatic, degenerative)

2. Absolute stenosis (anteroposterior canal diameter <10 mm)

3. Relative stenosis (anteroposterior canal diameter 10 to 13 mm)

4. Pavlov (Torg) ratio (canal/vertebral body width) should be 1.0.

Ratio of less than 0.80 or a sagittal diameter of less than 13 mm is considered a significant risk factor for later neurologic involvement.

Ratio of less than 0.80 or a sagittal diameter of less than 13 mm is considered a significant risk factor for later neurologic involvement.

5. Minor trauma such as hyperextension may lead to a central cord syndrome, even without overt skeletal injury.

6. Surgery may serve a prophylactic function but is usually reserved for patients who develop myelopathy or radiculopathy.

Cervical spine involvement is common in rheumatoid arthritis (occurring in up to 90% of patients) and is more common with long-standing disease and multiple joint involvement.

Cervical spine involvement is common in rheumatoid arthritis (occurring in up to 90% of patients) and is more common with long-standing disease and multiple joint involvement.

Neurologic impairment (weakness, decreased sensation, hyperreflexia) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis usually occurs gradually and is often overlooked or attributed to other joint disease.

Neurologic impairment (weakness, decreased sensation, hyperreflexia) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis usually occurs gradually and is often overlooked or attributed to other joint disease.

Neurologic impairment with rheumatoid arthritis has been classified by Ranawat (Table 8-3).

Neurologic impairment with rheumatoid arthritis has been classified by Ranawat (Table 8-3).

Table 8-3

Ranawat Classification of Neurologic Impairment in Rheumatoid Arthritis

| Grade | Characteristics |

| I | Subjective paresthesias, pain |

| II | Subjective weakness; upper motor neuron findings |

| III | Objective weakness; upper motor neuron findings |

| IIIA | Ambulatory |

| IIIB | Nonambulatory |

Surgery may not reverse significant neurologic deterioration, especially if a tight spinal canal is present, but it can stabilize it.

Surgery may not reverse significant neurologic deterioration, especially if a tight spinal canal is present, but it can stabilize it.

Look for subtle signs of neurologic involvement.

Look for subtle signs of neurologic involvement.

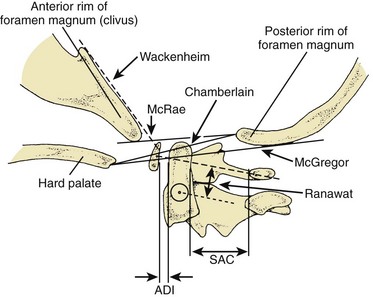

Assess the radiographic markers for impending neural compression (Figure 8-3).

Assess the radiographic markers for impending neural compression (Figure 8-3).

Indications for surgical stabilization:

Indications for surgical stabilization:

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis should have flexion/extension films before elective surgery.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis should have flexion/extension films before elective surgery.

2. Atlantoaxial subluxation—occurs in 50% to 80% of cases of rheumatoid arthritis and is often the result of pannus formation at synovial joints between the dens and the ring of C1, resulting in destruction of transverse ligament, dens, or both

Anterior subluxation of C1 on C2 is the most common finding, but posterior and lateral subluxation can also occur.

Anterior subluxation of C1 on C2 is the most common finding, but posterior and lateral subluxation can also occur.

Findings on examination may include limitation of motion, upper motor neuron signs, and weakness.

Findings on examination may include limitation of motion, upper motor neuron signs, and weakness.

Plain radiographs that include patient-controlled flexion and extension views are evaluated to determine the anterior atlanto–dens interval as well as the PADI.

Plain radiographs that include patient-controlled flexion and extension views are evaluated to determine the anterior atlanto–dens interval as well as the PADI.

Instability is present with motion of more than 3.5 mm on flexion and extension views, although radiographic instability in rheumatoid arthritis is common and not necessarily an indication for surgery.

Instability is present with motion of more than 3.5 mm on flexion and extension views, although radiographic instability in rheumatoid arthritis is common and not necessarily an indication for surgery.

C1-C2 motion of more than 9 to 10 mm or a PADI of less than 14 mm is associated with an increased risk of neurologic injury and usually requires surgical treatment.

C1-C2 motion of more than 9 to 10 mm or a PADI of less than 14 mm is associated with an increased risk of neurologic injury and usually requires surgical treatment.

Myelopathy, progressive neurologic impairment, and progressive instability are also indications for surgical stabilization, usually a posterior C1-C2 fusion.

Myelopathy, progressive neurologic impairment, and progressive instability are also indications for surgical stabilization, usually a posterior C1-C2 fusion.

Transarticular screw fixation (Magerl) across C1-C2 eliminates the need for halo immobilization associated with wiring alone.

Transarticular screw fixation (Magerl) across C1-C2 eliminates the need for halo immobilization associated with wiring alone.

Nonreducible atlantoaxial subluxation

Nonreducible atlantoaxial subluxation

Anterior cord compression because of pannus often resolves after posterior spinal fusion.

Anterior cord compression because of pannus often resolves after posterior spinal fusion.

Odontoidectomy should be reserved as a secondary procedure.

Odontoidectomy should be reserved as a secondary procedure.

Surgery is less successful in Ranawat grade IIIB patients but should be considered.

Surgery is less successful in Ranawat grade IIIB patients but should be considered.

Complications include pseudarthrosis (10%-20%) and adjacent segment involvement on long-term follow-up.

Complications include pseudarthrosis (10%-20%) and adjacent segment involvement on long-term follow-up.

3. Cranial settling (basilar invagination)

The second most common manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis in cervical spine

The second most common manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis in cervical spine

Forty percent of patients with rheumatoid arthritis

Forty percent of patients with rheumatoid arthritis

Cranial migration of the dens from erosion and bone loss between the occiput and C1-C2

Cranial migration of the dens from erosion and bone loss between the occiput and C1-C2

Often seen in combination with fixed atlantoaxial subluxation

Often seen in combination with fixed atlantoaxial subluxation

Measurements are shown in Figure 8-3.

Measurements are shown in Figure 8-3.

Progressive cranial migration or neurologic compromise may require operative intervention (occiput to C2 fusion).

Progressive cranial migration or neurologic compromise may require operative intervention (occiput to C2 fusion).

Cervicomedullary angle less than 135 degrees (on MRI) suggests impending neurologic impairment.

Cervicomedullary angle less than 135 degrees (on MRI) suggests impending neurologic impairment.

Transoral or retropharyngeal dens resection for brainstem compression

Transoral or retropharyngeal dens resection for brainstem compression

If there is any suggestion of cranial settling in cases of atlantoaxial subluxation, occipitocervical fusion is the conservative approach.

If there is any suggestion of cranial settling in cases of atlantoaxial subluxation, occipitocervical fusion is the conservative approach.

Occurs in 20% of cases of rheumatoid arthritis

Occurs in 20% of cases of rheumatoid arthritis

Seen in combination with upper cervical spine instability

Seen in combination with upper cervical spine instability

Radiographic markers of instability

Radiographic markers of instability

Subaxial subluxation of greater than 4 mm or more than 20% of the body is indicative of cord compression.

Subaxial subluxation of greater than 4 mm or more than 20% of the body is indicative of cord compression.

A cervical height index (cervical body height/width) of less than 2.00 approaches 100% sensitivity and specificity in predicting neurologic compromise.

A cervical height index (cervical body height/width) of less than 2.00 approaches 100% sensitivity and specificity in predicting neurologic compromise.

Posterior spinal fusion may be required for subluxation greater than 4 mm with intractable pain and neurologic compromise.

Posterior spinal fusion may be required for subluxation greater than 4 mm with intractable pain and neurologic compromise.

D Cervical spine and cord injuries—See Chapter 11, Trauma, for classification and treatment of cervical spine injuries.

Gunshot wounds are an increasing cause.

Gunshot wounds are an increasing cause.

The findings may be subtle; the significant morbidity and mortality rates associated with missed injuries have led to the current emphasis on cervical spine protection after polytrauma.

The findings may be subtle; the significant morbidity and mortality rates associated with missed injuries have led to the current emphasis on cervical spine protection after polytrauma.

Missed cervical spine injuries are the most common in the presence of a decreased level of consciousness, alcohol/drug intoxication, and head injury and in patients with multiple injuries.

Missed cervical spine injuries are the most common in the presence of a decreased level of consciousness, alcohol/drug intoxication, and head injury and in patients with multiple injuries.

Spinal shock usually involves a 24- to 72-hour period of paralysis, hypotonia, and areflexia.

Spinal shock usually involves a 24- to 72-hour period of paralysis, hypotonia, and areflexia.

Return of the bulbocavernosus reflex (anal sphincter contraction in response to squeezing the glans penis or tugging on the Foley catheter) signifies the end of spinal shock.

Return of the bulbocavernosus reflex (anal sphincter contraction in response to squeezing the glans penis or tugging on the Foley catheter) signifies the end of spinal shock.

Injuries below the thoracolumbar level (conus or cauda equina) may permanently interrupt the bulbocavernosus reflex.

Injuries below the thoracolumbar level (conus or cauda equina) may permanently interrupt the bulbocavernosus reflex.

After the conclusion of spinal shock, spasticity, hyperreflexia, and clonus progress over days to weeks.

After the conclusion of spinal shock, spasticity, hyperreflexia, and clonus progress over days to weeks.

In complete injuries, further neurologic improvement is minimal.

In complete injuries, further neurologic improvement is minimal.

3. Physical and neurologic examination

Facial injuries, hypotension, and localized tenderness or spasm should be investigated.

Facial injuries, hypotension, and localized tenderness or spasm should be investigated.

Careful neurologic examination to document the lowest remaining functional level and to assess the patient for the possibility of sacral sparing (sparing of posterior column function, indicating an incomplete spinal cord injury) is essential (see Figure 8-1).

Careful neurologic examination to document the lowest remaining functional level and to assess the patient for the possibility of sacral sparing (sparing of posterior column function, indicating an incomplete spinal cord injury) is essential (see Figure 8-1).

Complete cervical spine series (C1-T1)

Complete cervical spine series (C1-T1)

Oblique views to investigate facet subluxation, dislocations, or fractures

Oblique views to investigate facet subluxation, dislocations, or fractures

Replacing plain radiography as the initial imaging study in most trauma centers

Replacing plain radiography as the initial imaging study in most trauma centers

Highly sensitive and more easily obtained than appropriate cervical spine radiographs in most cases

Highly sensitive and more easily obtained than appropriate cervical spine radiographs in most cases

CT is useful for evaluating C1 fractures and assessing bone in the canal but may miss an axial plane fracture (type II odontoid).

CT is useful for evaluating C1 fractures and assessing bone in the canal but may miss an axial plane fracture (type II odontoid).

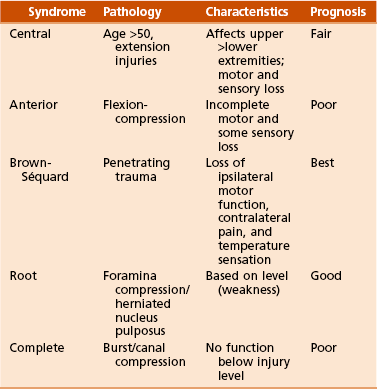

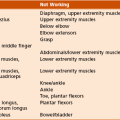

Figure 8-4![]() Incomplete spinal cord injury syndromes.

Incomplete spinal cord injury syndromes.

Most cord injury is due to contusion or compression, not transection.

Most cord injury is due to contusion or compression, not transection.

Sustained cord compression can lead to secondary injury and may result in more limited functional recovery.

Sustained cord compression can lead to secondary injury and may result in more limited functional recovery.

No function below a given level

No function below a given level

With complete injuries, an improvement of one nerve root level can be expected in 80% of the patients, and approximately 20% recover two functioning root levels.

With complete injuries, an improvement of one nerve root level can be expected in 80% of the patients, and approximately 20% recover two functioning root levels.

Defined as some sparing of distal motor or sensory function

Defined as some sparing of distal motor or sensory function

Three important generalizations regarding prognosis:

Three important generalizations regarding prognosis:

Anatomic classification of incomplete spinal cord injury (Table 8-4)

Anatomic classification of incomplete spinal cord injury (Table 8-4)

Presents as upper greater than lower extremity motor and sensory loss

Presents as upper greater than lower extremity motor and sensory loss

Often seen in patients with preexisting cervical spondylosis who sustain a hyperextension injury

Often seen in patients with preexisting cervical spondylosis who sustain a hyperextension injury

Cord is compressed anteriorly by osteophytes and posteriorly by the infolded ligamentum flavum.

Cord is compressed anteriorly by osteophytes and posteriorly by the infolded ligamentum flavum.

Cord is injured in the central gray matter, resulting in proportionately greater loss of motor function to the upper extremities than to the lower extremities.

Cord is injured in the central gray matter, resulting in proportionately greater loss of motor function to the upper extremities than to the lower extremities.

Independent ambulation is regained in approximately half of elderly patients and almost always in young patients.

Independent ambulation is regained in approximately half of elderly patients and almost always in young patients.

The second most common incomplete cord injury

The second most common incomplete cord injury

Damage is primarily in the anterior two thirds of the cord.

Damage is primarily in the anterior two thirds of the cord.

Posterior columns spared (proprioception and vibratory sensation)

Posterior columns spared (proprioception and vibratory sensation)

Patients demonstrate greater motor loss in the legs than the arms.

Patients demonstrate greater motor loss in the legs than the arms.

CT may demonstrate bony fragments compressing the anterior cord.

CT may demonstrate bony fragments compressing the anterior cord.

6. Treatment—See Chapter 11, Trauma.

Used acutely to realign the spine in the presence of a displaced fracture with or without neurologic injury

Used acutely to realign the spine in the presence of a displaced fracture with or without neurologic injury

Anterior decompression for incomplete injuries with persistent cord compression can lead to improvement of one to three levels, even with complete injuries. Also, stabilization may be indicated.

Anterior decompression for incomplete injuries with persistent cord compression can lead to improvement of one to three levels, even with complete injuries. Also, stabilization may be indicated.

Late decompression for up to 1 year may be effective in improving root return.

Late decompression for up to 1 year may be effective in improving root return.

Laminectomies are contraindicated except in the rare case of posterior compression from a fractured lamina.

Laminectomies are contraindicated except in the rare case of posterior compression from a fractured lamina.

Gunshot injury to the spine is treated surgically if there is progression of neurologic injury or if the bullet rests in the spinal canal.

Gunshot injury to the spine is treated surgically if there is progression of neurologic injury or if the bullet rests in the spinal canal.

Penetrating spine injuries accompanied by gastrointestinal perforation should be treated with antibiotics for 7 to 14 days.

Penetrating spine injuries accompanied by gastrointestinal perforation should be treated with antibiotics for 7 to 14 days.

Potentially negative outcomes are numerous and include neurologic injury, nonunion, and malunion.

Potentially negative outcomes are numerous and include neurologic injury, nonunion, and malunion.

Associated with greater than 3.5 mm of subluxation and greater than 11 degrees of difference in angulation between adjacent motion segments

Associated with greater than 3.5 mm of subluxation and greater than 11 degrees of difference in angulation between adjacent motion segments

8. Prognosis—The Frankel classification is useful when assessing functional recovery from spinal cord injury (Table 8-5).

Table 8-5![]()

Frankel Classification of Cervical Spine Injuries

| Frankel Grade | Function |

| A | Complete paralysis |

| B | Sensory function only below injury level |

| C | Incomplete motor function (grades 1-2 of 5) below injury level |

| D | Fair to good (useful) motor function (grades 3-4 of 5) below injury level |

| E | Normal function (grade 5 of 5) |

E Sports-related cervical spine injuries

Commonly associated with stretching of the upper brachial plexus by bending the neck away from the depressed shoulder or neck extension toward the painful shoulder in the setting of foraminal stenosis (root irritation)

Commonly associated with stretching of the upper brachial plexus by bending the neck away from the depressed shoulder or neck extension toward the painful shoulder in the setting of foraminal stenosis (root irritation)

Symptoms include burning dysesthesia and weakness in the involved extremity.

Symptoms include burning dysesthesia and weakness in the involved extremity.

Fracture or acute HNP should be ruled out.

Fracture or acute HNP should be ruled out.

The athlete with a neck injury should be further evaluated for cervical pain, tenderness, or persisting neurologic symptoms.

The athlete with a neck injury should be further evaluated for cervical pain, tenderness, or persisting neurologic symptoms.

Usually seen after axial load injury (spearing) but may also be seen after forced hyperextension or hyperflexion

Usually seen after axial load injury (spearing) but may also be seen after forced hyperextension or hyperflexion

Presents as bilateral burning paresthesia and weakness or paralysis

Presents as bilateral burning paresthesia and weakness or paralysis

The third and fourth cervical levels are the most commonly affected.

The third and fourth cervical levels are the most commonly affected.

It has no definitive association with future permanent neurologic injury.

It has no definitive association with future permanent neurologic injury.

Patients with concurrent pathologic conditions, including instability, HNP, degenerative changes, and symptoms that last more than 36 hours, should be prohibited from participating in contact sports.

Patients with concurrent pathologic conditions, including instability, HNP, degenerative changes, and symptoms that last more than 36 hours, should be prohibited from participating in contact sports.

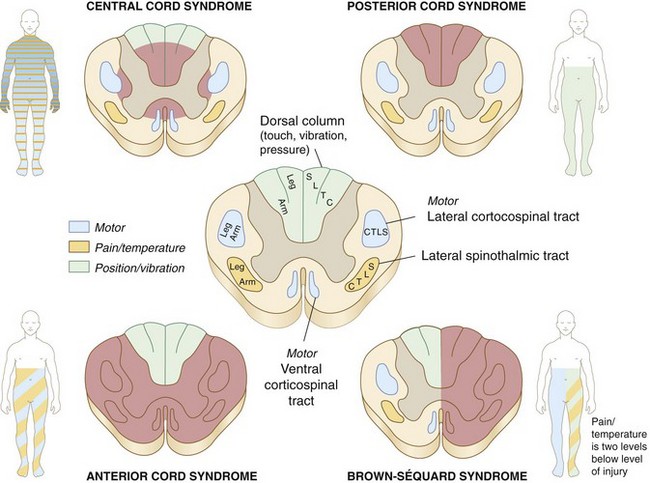

A Differential diagnosis—The physical examination, imaging studies, and laboratory tests assist with the differential diagnosis (Table 8-6).

Table 8-6![]()

Differential Diagnosis of Disorders in the Lumbar Spine

Modified from Weinstein JN, Wiesel SW: The lumbar spine, Philadelphia, 1990, WB Saunders, 1990, p 360.

B Herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP)

Aging results in loss of water content

Aging results in loss of water content

Myxomatous changes, resulting in herniation of nuclear material

Myxomatous changes, resulting in herniation of nuclear material

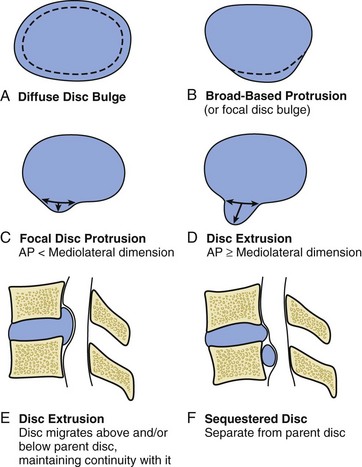

Figure 8-5 Types of disc herniation.

Discs can protrude (bulging nucleus, intact annulus).

Discs can protrude (bulging nucleus, intact annulus).

Disc extrusion (through the annulus but confined by the posterior longitudinal ligament)

Disc extrusion (through the annulus but confined by the posterior longitudinal ligament)

Disc sequestration (disc material free in canal).

Disc sequestration (disc material free in canal).

HNP usually a disease of young and middle-aged adults; in older patients the nucleus desiccates and is less likely to herniate

HNP usually a disease of young and middle-aged adults; in older patients the nucleus desiccates and is less likely to herniate

Relatively uncommon (1% of all surgical HNPs)

Relatively uncommon (1% of all surgical HNPs)

Typically involves the middle to lower thoracic levels

Typically involves the middle to lower thoracic levels

Thoracic HNP can be divided into central, posterolateral, and lateral herniations.

Thoracic HNP can be divided into central, posterolateral, and lateral herniations.

Underlying Scheuermann disease may predispose patients to develop HNP.

Underlying Scheuermann disease may predispose patients to develop HNP.

Presents as the onset of back or chest pain

Presents as the onset of back or chest pain

May include radicular symptoms

May include radicular symptoms

Immobilization, analgesics, and nerve blocks are sometimes helpful for radiculopathy.

Immobilization, analgesics, and nerve blocks are sometimes helpful for radiculopathy.

Usually performed through an anterior transthoracic approach for midline or central HNP (including anterior discectomy and hemicorpectomy as needed)

Usually performed through an anterior transthoracic approach for midline or central HNP (including anterior discectomy and hemicorpectomy as needed)

Transpedicular approach for lateral HNP

Transpedicular approach for lateral HNP

Indicated in the presence of myelopathy or persistent, unremitting radicular pain

Indicated in the presence of myelopathy or persistent, unremitting radicular pain

Introduction—A major cause of morbidity with a major financial impact in the United States, this disc disease:

Introduction—A major cause of morbidity with a major financial impact in the United States, this disc disease:

Usually involves the L4 to L5 disc (the “backache disc”), followed closely by L5 to S1.

Usually involves the L4 to L5 disc (the “backache disc”), followed closely by L5 to S1.

Most herniations are posterolateral (where the posterior longitudinal ligament is the weakest) and may present as back pain and nerve root pain/sciatica involving the lower nerve root at that level (L5 at the L4-L5 level).

Most herniations are posterolateral (where the posterior longitudinal ligament is the weakest) and may present as back pain and nerve root pain/sciatica involving the lower nerve root at that level (L5 at the L4-L5 level).

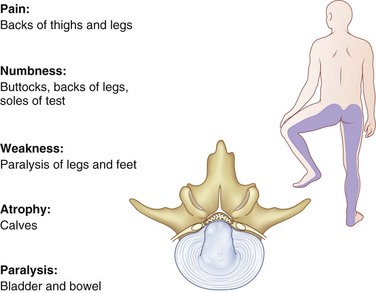

Central prolapse is often associated with back pain only; however, acute insults may precipitate a cauda equina compression syndrome (Figure 8-7).

Central prolapse is often associated with back pain only; however, acute insults may precipitate a cauda equina compression syndrome (Figure 8-7).

This syndrome is a surgical emergency that usually presents as bilateral buttock and lower extremity pain as well as bowel or bladder dysfunction (usually urinary retention), saddle anesthesia, and varying degrees of loss of lower extremity motor or sensory function.

This syndrome is a surgical emergency that usually presents as bilateral buttock and lower extremity pain as well as bowel or bladder dysfunction (usually urinary retention), saddle anesthesia, and varying degrees of loss of lower extremity motor or sensory function.

Digital rectal examination and evaluation of perianal sensation are important for the immediate diagnosis.

Digital rectal examination and evaluation of perianal sensation are important for the immediate diagnosis.

Immediate MRI and surgery (if the test results are positive) are indicated to arrest progression of neurologic loss.

Immediate MRI and surgery (if the test results are positive) are indicated to arrest progression of neurologic loss.

Although the prognosis for recovery is guarded in most cases, surgical decompression within the first 48 hours was reported to lead to best outcomes.

Although the prognosis for recovery is guarded in most cases, surgical decompression within the first 48 hours was reported to lead to best outcomes.

History of an acute injury or precipitating event should be investigated.

History of an acute injury or precipitating event should be investigated.

Location of symptoms (especially pain radiating to the extremity)

Location of symptoms (especially pain radiating to the extremity)

Character of pain—referred pain in mesodermal tissues of the same embryologic origin

Character of pain—referred pain in mesodermal tissues of the same embryologic origin

Localizes to buttocks or posterior thighs

Localizes to buttocks or posterior thighs

Must be differentiated from true radicular pain due to nerve root impingement (typically distal to the knee)

Must be differentiated from true radicular pain due to nerve root impingement (typically distal to the knee)

Complete review of symptoms (including psychiatric history)

Complete review of symptoms (including psychiatric history)

The finding of an “inverted-V” triad of hysteria, hypochondriasis, and depression on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory has been identified as a significant adverse risk factor for lumbar disc surgery.

The finding of an “inverted-V” triad of hysteria, hypochondriasis, and depression on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory has been identified as a significant adverse risk factor for lumbar disc surgery.

Psychosocial evaluation, pain drawings, and psychological testing are helpful in some cases.

Psychosocial evaluation, pain drawings, and psychological testing are helpful in some cases.

Physical examination should include:

Physical examination should include:

Observation (change in posture, gait)

Observation (change in posture, gait)

Palpation of the posterior spine (spasm, localized tenderness)

Palpation of the posterior spine (spasm, localized tenderness)

Measurement of range of motion (decreased flexion)

Measurement of range of motion (decreased flexion)

Vascular evaluation (distal pulses)

Vascular evaluation (distal pulses)

Abdominal (bruits and pulsatile masses) and rectal examination

Abdominal (bruits and pulsatile masses) and rectal examination

Neurologic evaluation (see Figure 8-1)

Neurologic evaluation (see Figure 8-1)

Tension signs such as straight-leg raising or the bowstring sign (L4-L5 or L5-S1) and the femoral nerve stretch test (L2-L3 or L3-L4) are critical findings that suggest HNP and are important when discectomy is considered.

Tension signs such as straight-leg raising or the bowstring sign (L4-L5 or L5-S1) and the femoral nerve stretch test (L2-L3 or L3-L4) are critical findings that suggest HNP and are important when discectomy is considered.

A positive contralateral straight-leg raising test (pain in the affected buttock/leg when the opposite leg is raised) is the most specific test for HNP.

A positive contralateral straight-leg raising test (pain in the affected buttock/leg when the opposite leg is raised) is the most specific test for HNP.

A large central disc herniation at one level may impinge on more than one nerve root.

A large central disc herniation at one level may impinge on more than one nerve root.

Inappropriate signs and symptoms (Waddell) are also important to note.

Inappropriate signs and symptoms (Waddell) are also important to note.

Indicated before proceeding with special tests to rule out other disorders, such as isthmic defects.

Indicated before proceeding with special tests to rule out other disorders, such as isthmic defects.

However, most plain radiographic findings are nonspecific and plain radiography can usually be deferred for 6 weeks.

However, most plain radiographic findings are nonspecific and plain radiography can usually be deferred for 6 weeks.

These are effective when used as confirmatory studies.

These are effective when used as confirmatory studies.

CT is noninvasive and helpful for demonstrating bony stenosis and identifying lateral pathologic conditions.

CT is noninvasive and helpful for demonstrating bony stenosis and identifying lateral pathologic conditions.

Imaging of neural compression may be improved if combined with myelography.

Imaging of neural compression may be improved if combined with myelography.

As the neuroradiographic test of choice in most cases, it is superior for identifying cord disorders, neural tumors, and disc disorders.

As the neuroradiographic test of choice in most cases, it is superior for identifying cord disorders, neural tumors, and disc disorders.

Multiplanar views allow imaging of central, foraminal, and extraforaminal stenosis.

Multiplanar views allow imaging of central, foraminal, and extraforaminal stenosis.

It can demonstrate the state of hydration of the discs and visualize the marrow of the vertebral bodies, thus representing an excellent modality to screen for tumor or infection.

It can demonstrate the state of hydration of the discs and visualize the marrow of the vertebral bodies, thus representing an excellent modality to screen for tumor or infection.

False-positive findings are common (occurring in 35% of those younger than 40 years old and in 93% of those older than 60 years old) and therefore require correlation with the history and physical examination.

False-positive findings are common (occurring in 35% of those younger than 40 years old and in 93% of those older than 60 years old) and therefore require correlation with the history and physical examination.

More than half of the patients who seek treatment for low back pain recover in 1 week, and 90% recover within 1 to 3 months.

More than half of the patients who seek treatment for low back pain recover in 1 week, and 90% recover within 1 to 3 months.

Half of the patients with sciatica recover in 1 month.

Half of the patients with sciatica recover in 1 month.

Instruction should include avoiding rotation and flexion to avoid the increased disc pressure associated with these activities.

Instruction should include avoiding rotation and flexion to avoid the increased disc pressure associated with these activities.

Progressive ambulation is successful in returning most patients to their normal function.

Progressive ambulation is successful in returning most patients to their normal function.

Bed rest is shown to be no more effective than continued normal activity in terms of patient improvement.

Bed rest is shown to be no more effective than continued normal activity in terms of patient improvement.

This treatment is followed by back rehabilitation and a fitness program.

This treatment is followed by back rehabilitation and a fitness program.

Aerobic conditioning and education are the most important factors in avoiding missed workdays due to disc disease and returning patients to work.

Aerobic conditioning and education are the most important factors in avoiding missed workdays due to disc disease and returning patients to work.

Failure of nonoperative therapy

Failure of nonoperative therapy

If patients fail to improve within 6 weeks of conservative care, further evaluation is indicated.

If patients fail to improve within 6 weeks of conservative care, further evaluation is indicated.

Those patients with predominantly low back pain may require bone scan, MRI, and medical workup to rule out spinal tumors or infection.

Those patients with predominantly low back pain may require bone scan, MRI, and medical workup to rule out spinal tumors or infection.

In patients who have predominantly leg pain (sciatica) and in whom conservative therapy fails, a trial of lumbar epidural steroids may be helpful in 40% to 60% of patients.

In patients who have predominantly leg pain (sciatica) and in whom conservative therapy fails, a trial of lumbar epidural steroids may be helpful in 40% to 60% of patients.

Additional studies (MRI) are performed in patients who after 6 to 12 weeks continue to be symptomatic with pain, neurologic deficits, and positive nerve tension signs.

Additional studies (MRI) are performed in patients who after 6 to 12 weeks continue to be symptomatic with pain, neurologic deficits, and positive nerve tension signs.

As a rule, these studies are preoperative tests and should be done to confirm clinical suspicions.

As a rule, these studies are preoperative tests and should be done to confirm clinical suspicions.

Patients with positive study results, neurologic findings, tension signs, and predominantly sciatic symptoms without mitigating psychosocial factors are the best candidates for surgical discectomy.

Patients with positive study results, neurologic findings, tension signs, and predominantly sciatic symptoms without mitigating psychosocial factors are the best candidates for surgical discectomy.

Standard partial laminotomy and discectomy are the most commonly performed surgical procedures.

Standard partial laminotomy and discectomy are the most commonly performed surgical procedures.

Operative positioning requires the abdomen to be free to decrease pressure on the inferior vena cava and consequently on the epidural veins.

Operative positioning requires the abdomen to be free to decrease pressure on the inferior vena cava and consequently on the epidural veins.

At 2-year follow-up there were no significant differences in primary outcome measures for operative compared with nonoperative groups.

At 2-year follow-up there were no significant differences in primary outcome measures for operative compared with nonoperative groups.

Trends favoring surgical intervention in primary outcome measures

Trends favoring surgical intervention in primary outcome measures

Statistically significant improvement in secondary outcome measures for surgical intervention

Statistically significant improvement in secondary outcome measures for surgical intervention

Patient prognosis depends on the anatomy of the disc at surgery, with recurrence rates being higher for patients with massive posterior annulus loss or without a contained defect (20%-40%).

Patient prognosis depends on the anatomy of the disc at surgery, with recurrence rates being higher for patients with massive posterior annulus loss or without a contained defect (20%-40%).

Contained disc defects or disc fissuring correlates with better clinical outcomes and lower recurrence of symptoms (1%-10%).

Contained disc defects or disc fissuring correlates with better clinical outcomes and lower recurrence of symptoms (1%-10%).

Workers’ compensation patients are more likely to continue to receive disability compensation and have worse symptoms, functional status, and satisfaction outcomes.

Workers’ compensation patients are more likely to continue to receive disability compensation and have worse symptoms, functional status, and satisfaction outcomes.

Minimally invasive surgical treatment

Minimally invasive surgical treatment

Percutaneous discectomy currently has limited indications in the treatment of lumbar disc disease, with no long-term follow-up studies proving its efficacy.

Percutaneous discectomy currently has limited indications in the treatment of lumbar disc disease, with no long-term follow-up studies proving its efficacy.

Endoscopic discectomy does allow direct visualization and can address sequestered fragments and lateral recess stenosis.

Endoscopic discectomy does allow direct visualization and can address sequestered fragments and lateral recess stenosis.

Intradiscal enzyme therapy has fallen out of favor because of its questionable efficacy and serious complications.

Intradiscal enzyme therapy has fallen out of favor because of its questionable efficacy and serious complications.

Complications—fortunately rare, but can be devastating

Complications—fortunately rare, but can be devastating

Vascular injury—may occur during attempts at disc removal if curets are allowed to penetrate the anterior longitudinal ligament

Vascular injury—may occur during attempts at disc removal if curets are allowed to penetrate the anterior longitudinal ligament

Intraoperative pulsatile bleeding due to deep penetration is treated with rapid wound closure, intravenous administration of fluids and blood, repositioning the patient, and a transabdominal approach to find and stop the source of bleeding.

Intraoperative pulsatile bleeding due to deep penetration is treated with rapid wound closure, intravenous administration of fluids and blood, repositioning the patient, and a transabdominal approach to find and stop the source of bleeding.

Late sequelae of vascular injuries may include delayed hemorrhage, pseudoaneurysm, and arteriovenous fistula formation.

Late sequelae of vascular injuries may include delayed hemorrhage, pseudoaneurysm, and arteriovenous fistula formation.

Nerve root injury—more common with anomalous nerve roots

Nerve root injury—more common with anomalous nerve roots

Failed back syndrome—often the result of poor patient selection; other causes include:

Failed back syndrome—often the result of poor patient selection; other causes include:

Recurrent herniation (usually acute recurrence of signs/symptoms after a 6- to 12-month pain-free interval)

Recurrent herniation (usually acute recurrence of signs/symptoms after a 6- to 12-month pain-free interval)

Unrecognized lateral stenosis (may be the most common)

Unrecognized lateral stenosis (may be the most common)

Epidural fibrosis occurs at about 3 months postoperatively and may be associated with back or leg pain.

Epidural fibrosis occurs at about 3 months postoperatively and may be associated with back or leg pain.

Primary repair necessary to avoid the development of a pseudomeningocele or spinal fluid fistula

Primary repair necessary to avoid the development of a pseudomeningocele or spinal fluid fistula

More common during revision surgery

More common during revision surgery

Fibrin adhesive sealant may be a useful adjunct for effecting dural closure.

Fibrin adhesive sealant may be a useful adjunct for effecting dural closure.

Bed rest and subarachnoid drain placement are advocated if cerebrospinal fluid leak is suspected postoperatively.

Bed rest and subarachnoid drain placement are advocated if cerebrospinal fluid leak is suspected postoperatively.

If tear is adequately repaired, clinical outcomes are generally unaffected.

If tear is adequately repaired, clinical outcomes are generally unaffected.

Wound infection (approximately 1% in open discectomy)

Wound infection (approximately 1% in open discectomy)

Discitis (3-6 weeks postoperatively, with rapid onset of severe back pain)

Discitis (3-6 weeks postoperatively, with rapid onset of severe back pain)

Cauda equina syndrome—secondary to extruded disc, surgical trauma, and hematoma

Cauda equina syndrome—secondary to extruded disc, surgical trauma, and hematoma

Back pain greater than leg pain

Back pain greater than leg pain

Radiographs are negative for instability but may show disc space narrowing or other stigmata of spondylosis.

Radiographs are negative for instability but may show disc space narrowing or other stigmata of spondylosis.

MRI reveals decreased signal intensity in the disc space on T2 weighting (dark disc).

MRI reveals decreased signal intensity in the disc space on T2 weighting (dark disc).

Discography is a useful preoperative study to correlate MRI findings with a clinically significant pain generator.

Discography is a useful preoperative study to correlate MRI findings with a clinically significant pain generator.

The study should be performed at multiple levels to include all abnormal levels and one or more normal levels on MRI.

The study should be performed at multiple levels to include all abnormal levels and one or more normal levels on MRI.

To be considered reliably positive, the procedure should elicit pain after injection similar to that usually described by the patient (concordant pain) and should involve at least one minimally painful, nonconcordant level.

To be considered reliably positive, the procedure should elicit pain after injection similar to that usually described by the patient (concordant pain) and should involve at least one minimally painful, nonconcordant level.

If extended nonoperative treatment has failed and the patient has a positive MRI and discogram, interbody fusion can be performed from either an anterior or a retroperitoneal approach or through a posterior midline (posterior lumbar) or posterior transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion approach.

If extended nonoperative treatment has failed and the patient has a positive MRI and discogram, interbody fusion can be performed from either an anterior or a retroperitoneal approach or through a posterior midline (posterior lumbar) or posterior transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion approach.

Fusion is performed with structural constructs (femoral ring allografts or interbody fusion cages) in the disc space.

Fusion is performed with structural constructs (femoral ring allografts or interbody fusion cages) in the disc space.

Intradiscal electrothermy—involves percutaneously heating the fibers of the annulus fibrosus to reconfigure the collagen fibers, thus restoring the mechanical integrity of the disc.

Intradiscal electrothermy—involves percutaneously heating the fibers of the annulus fibrosus to reconfigure the collagen fibers, thus restoring the mechanical integrity of the disc.

This may be effective in early conditions (<50% loss of disc height) but not in more advanced disease

This may be effective in early conditions (<50% loss of disc height) but not in more advanced disease

Long-term follow-up suggests that symptomatic improvement often lasts less than 1 year, and this procedure has been largely abandoned.

Long-term follow-up suggests that symptomatic improvement often lasts less than 1 year, and this procedure has been largely abandoned.

Another surgical option for patients with degenerative disc disease at a single level (L4-S1) in the lumbar spine with the absence of spondylolisthesis and no relief from 6 months of nonoperative therapy

Another surgical option for patients with degenerative disc disease at a single level (L4-S1) in the lumbar spine with the absence of spondylolisthesis and no relief from 6 months of nonoperative therapy

In direct comparison with anterior interbody fusion, total disc arthroplasty showed equivalent clinical results and no catastrophic failures at 2-year follow-up.

In direct comparison with anterior interbody fusion, total disc arthroplasty showed equivalent clinical results and no catastrophic failures at 2-year follow-up.

Significant concerns include long-term results, design issues, cost, and the safety of revision procedures.

Significant concerns include long-term results, design issues, cost, and the safety of revision procedures.

D Lumbar segmental instability—present when normal loads produce abnormal spinal motion

The most common symptom is mechanical back pain, although “dynamic” stenosis can occur, leading to radicular symptoms.

The most common symptom is mechanical back pain, although “dynamic” stenosis can occur, leading to radicular symptoms.

The most consistent clinical sign is the “instability catch” (sudden, painful catch with extension from a flexed position).

The most consistent clinical sign is the “instability catch” (sudden, painful catch with extension from a flexed position).

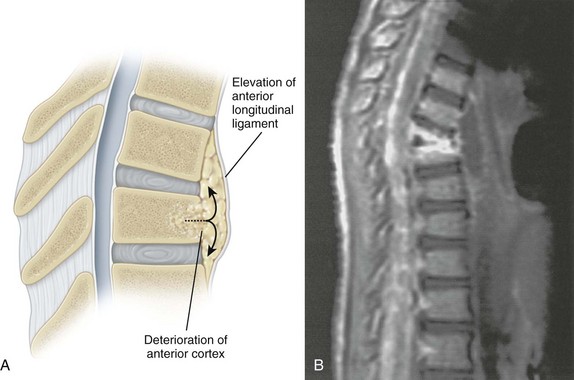

Degenerative lumbar disc disease is indicated by disc space narrowing.

Degenerative lumbar disc disease is indicated by disc space narrowing.

A combination of annulus damage and disc space narrowing may reduce the disc’s ability to resist rotatory forces.

A combination of annulus damage and disc space narrowing may reduce the disc’s ability to resist rotatory forces.

Continuing degeneration or facet subluxation may then lead to instability.

Continuing degeneration or facet subluxation may then lead to instability.

Traction spurs (horizontal and below disc margin),

Traction spurs (horizontal and below disc margin),

Angular changes greater than 10 degrees (20 degrees at L5-S1) on flexion films

Angular changes greater than 10 degrees (20 degrees at L5-S1) on flexion films

Translational motion greater than 3-4 mm (6 mm at L5-S1) with flexion-extension views are characteristic of lumbar instability but are difficult to quantify and may not correlate with clinical symptoms.

Translational motion greater than 3-4 mm (6 mm at L5-S1) with flexion-extension views are characteristic of lumbar instability but are difficult to quantify and may not correlate with clinical symptoms.

Progressive subluxation or deformity after decompressive surgery can occur after removal of one or more facet joints.

Progressive subluxation or deformity after decompressive surgery can occur after removal of one or more facet joints.

Surgical treatment options do not have clearly defined indications, but posterolateral fusion is the standard treatment.

Surgical treatment options do not have clearly defined indications, but posterolateral fusion is the standard treatment.

The use of pedicle screw instrumentation is well established, with fusion rates approaching 90% in nonsmokers for one- or two-level fusions.

The use of pedicle screw instrumentation is well established, with fusion rates approaching 90% in nonsmokers for one- or two-level fusions.

The anatomic landmark for pedicle screw insertion in the lumbar spine is the junction of the transverse process, pars intra-articularis, and lateral aspect of the superior articular facet.

The anatomic landmark for pedicle screw insertion in the lumbar spine is the junction of the transverse process, pars intra-articularis, and lateral aspect of the superior articular facet.

Adjacent-level degeneration can occur in these patients.

Adjacent-level degeneration can occur in these patients.

In large studies, the rates of symptomatic degeneration at an adjacent spinal level are 15% at 5 years and about 40% at 10 years, with no correlation with the number of levels fused or preoperative degeneration.

In large studies, the rates of symptomatic degeneration at an adjacent spinal level are 15% at 5 years and about 40% at 10 years, with no correlation with the number of levels fused or preoperative degeneration.

In achieving fusion, a posterior iliac crest bone graft is the gold standard and is associated with a significantly lower risk of postoperative complications than an anterior iliac crest bone graft.

In achieving fusion, a posterior iliac crest bone graft is the gold standard and is associated with a significantly lower risk of postoperative complications than an anterior iliac crest bone graft.

The use of NSAIDs, including aspirin and ketorolac (Toradol) has been shown to decrease spinal fusion rates.

The use of NSAIDs, including aspirin and ketorolac (Toradol) has been shown to decrease spinal fusion rates.

The use of alendronate has been shown to decrease spinal fusion rates in animal models

The use of alendronate has been shown to decrease spinal fusion rates in animal models

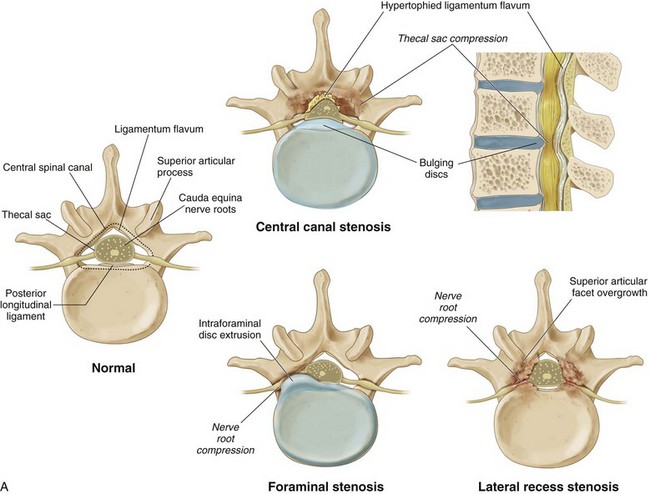

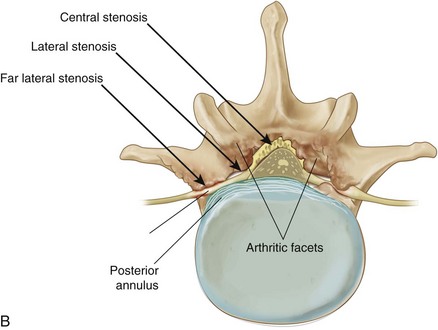

E Spinal stenosis (Figure 8-8)

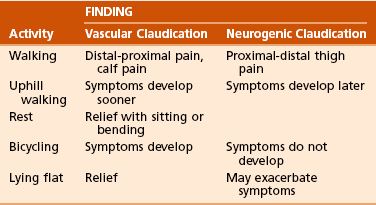

1. Introduction—Spinal stenosis is narrowing of the spinal canal or neural foramina, producing nerve root compression, root ischemia, and a variable syndrome of back and leg pain.

Central stenosis—thecal sac compression

Central stenosis—thecal sac compression

The central canal is defined as the space posterior to the posterior longitudinal ligament, anterior to the ligamentum flavum and laminae, and bordered laterally by the medial border of the superior articular process.

The central canal is defined as the space posterior to the posterior longitudinal ligament, anterior to the ligamentum flavum and laminae, and bordered laterally by the medial border of the superior articular process.

Soft tissue structures, including the hypertrophied ligamentum flavum, facet capsule, and bulging disc, may contribute as much as 40% to thecal sac compression.

Soft tissue structures, including the hypertrophied ligamentum flavum, facet capsule, and bulging disc, may contribute as much as 40% to thecal sac compression.

Absolute stenosis is defined as a cross-sectional area of less than 100 mm2 or less than 10 mm of anteroposterior diameter as seen on CT cross section.

Absolute stenosis is defined as a cross-sectional area of less than 100 mm2 or less than 10 mm of anteroposterior diameter as seen on CT cross section.

Central stenosis is more common in men because their spinal canal is smaller at the L3 to L5 levels than in women

Central stenosis is more common in men because their spinal canal is smaller at the L3 to L5 levels than in women

It affects an older population more than lateral recess stenosis does.

It affects an older population more than lateral recess stenosis does.

Lateral recess stenosis—nerve root compression

Lateral recess stenosis—nerve root compression

The lateral recess is defined by the superior articular facet posteriorly, the thecal sac medially, the pedicle laterally, and the posterolateral vertebral body anteriorly.

The lateral recess is defined by the superior articular facet posteriorly, the thecal sac medially, the pedicle laterally, and the posterolateral vertebral body anteriorly.

It comprises compression of individual nerve roots by the medial overgrowth of the superior articular facet at a given facet joint.

It comprises compression of individual nerve roots by the medial overgrowth of the superior articular facet at a given facet joint.

Foraminal stenosis—nerve root compression

Foraminal stenosis—nerve root compression

The intervertebral foramen is bordered superiorly and inferiorly by the adjacent level pedicles, posteriorly by the facet joint and lateral extensions of the ligamentum flavum, and anteriorly by the adjacent vertebral bodies and disc.

The intervertebral foramen is bordered superiorly and inferiorly by the adjacent level pedicles, posteriorly by the facet joint and lateral extensions of the ligamentum flavum, and anteriorly by the adjacent vertebral bodies and disc.

Normal foraminal height is 20 to 30 mm; superior width is 8 to 10 mm.

Normal foraminal height is 20 to 30 mm; superior width is 8 to 10 mm.

Stenosis usually is not symptomatic until patients reach late middle age; men are affected somewhat more often than women.

Stenosis usually is not symptomatic until patients reach late middle age; men are affected somewhat more often than women.

“Tandem stenosis” is the occurrence of both cervical and lumbar stenosis that often presents as both neurogenic claudication and myelopathy.

“Tandem stenosis” is the occurrence of both cervical and lumbar stenosis that often presents as both neurogenic claudication and myelopathy.

Etiology—congenital versus acquired

Etiology—congenital versus acquired

Patient history and physical examination

Patient history and physical examination

Symptoms include insidious pain and paresthesias with ambulation or prolonged standing and are relieved by sitting or with flexion of the spine.

Symptoms include insidious pain and paresthesias with ambulation or prolonged standing and are relieved by sitting or with flexion of the spine.

Patients commonly complain of lower extremity pain, usually in the buttock and thigh, with numbness or “giving way.”

Patients commonly complain of lower extremity pain, usually in the buttock and thigh, with numbness or “giving way.”

Although typical with HNP, a history of radiating leg pain in a true dermatomal distribution is relatively uncommon in those with spinal stenosis.

Although typical with HNP, a history of radiating leg pain in a true dermatomal distribution is relatively uncommon in those with spinal stenosis.

Imaging—Further workup may include:

Imaging—Further workup may include:

Interspace narrowing due to disc degeneration

Interspace narrowing due to disc degeneration

Flattening of the lordotic curve

Flattening of the lordotic curve

Subluxation and degenerative changes of the facet joints may also be seen.

Subluxation and degenerative changes of the facet joints may also be seen.

Electromyography/nerve conduction velocity testing may be used.

Electromyography/nerve conduction velocity testing may be used.

Impingement of nerve roots lateral to the thecal sac as they pass through the lateral recess and into the neural foramen

Impingement of nerve roots lateral to the thecal sac as they pass through the lateral recess and into the neural foramen

Associated with facet joint arthropathy (superior articular process enlargement) and disc disease (Figure 8-8, B)

Associated with facet joint arthropathy (superior articular process enlargement) and disc disease (Figure 8-8, B)

Subarticular compression consists of compression between the medial aspect of a hypertrophic superior articular facet and the posterior aspect of the vertebral body and disc.

Subarticular compression consists of compression between the medial aspect of a hypertrophic superior articular facet and the posterior aspect of the vertebral body and disc.

Hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum and/or ventral facet joint capsule and vertebral body osteophyte/disc exacerbates the stenosis.

Hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum and/or ventral facet joint capsule and vertebral body osteophyte/disc exacerbates the stenosis.

After failure of nonoperative treatment, decompression of the hypertrophied lamina and ligamentum flavum and partial facetectomy are usually successful.

After failure of nonoperative treatment, decompression of the hypertrophied lamina and ligamentum flavum and partial facetectomy are usually successful.

Fusion may be necessary if instability is present or created.

Fusion may be necessary if instability is present or created.

Nerve root compression can occur at more than one level and must be completely decompressed to relieve the symptoms.

Nerve root compression can occur at more than one level and must be completely decompressed to relieve the symptoms.

Intraforaminal disc protrusion

Intraforaminal disc protrusion

Impingement of the tip of the superior facet

Impingement of the tip of the superior facet

Lower lumbar areas are usually involved because the foramina decrease in size as the size of the nerve root increases.

Lower lumbar areas are usually involved because the foramina decrease in size as the size of the nerve root increases.

Foraminal stenosis affects the exiting (upper) root (L4 at L4-L5) at a motion segment.

Foraminal stenosis affects the exiting (upper) root (L4 at L4-L5) at a motion segment.

Pain may be the result of intraneural edema and demyelination.

Pain may be the result of intraneural edema and demyelination.

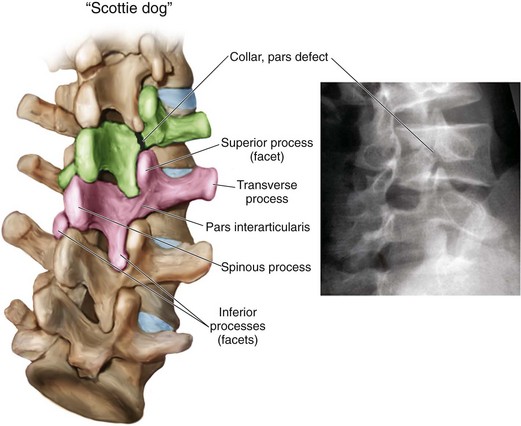

F Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis

1. Spondylolysis—defect in the pars interarticularis

One of the most common causes of low back pain in children and adolescents

One of the most common causes of low back pain in children and adolescents

Fatigue fracture from repetitive hyperextension stresses

Fatigue fracture from repetitive hyperextension stresses

Plain lateral radiographs demonstrate 80% of the lesions.

Plain lateral radiographs demonstrate 80% of the lesions.

Another 15% are visible on oblique radiographs, which show a defect in the neck of the “Scottie dog.”

Another 15% are visible on oblique radiographs, which show a defect in the neck of the “Scottie dog.”

CT, bone scanning, and (more recently) single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) may be helpful in identifying subtle defects.

CT, bone scanning, and (more recently) single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) may be helpful in identifying subtle defects.

2. Spondylolisthesis—forward slippage of one vertebra on another

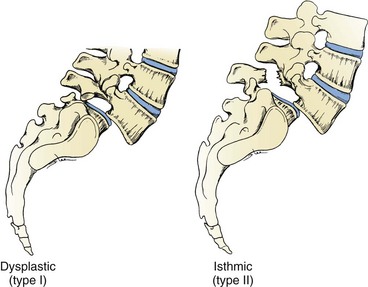

Etiology—six types (Newman, Wiltse, McNab) (Table 8-9; Figures 8-9 and 8-10)

Etiology—six types (Newman, Wiltse, McNab) (Table 8-9; Figures 8-9 and 8-10)

Table 8-9

| Type | Age | Pathology/Other |

| I—Dysplastic | Child | Congenital dysplasia of S1 superior facet |

| II—Isthmic* | 5-50 yr | Predisposition leading to elongation/fracture of pars (L5-S1) |

| III—Degenerative | >40 yr | Facet arthrosis leading to subluxation (L4-L5) |

| IV—Traumatic | Any age | Acute fracture other than pars |

| V—Pathologic | Any age | Incompetence of bony elements |

| VI—Postsurgical | Adult | Excessive resection of neural arches/facets |

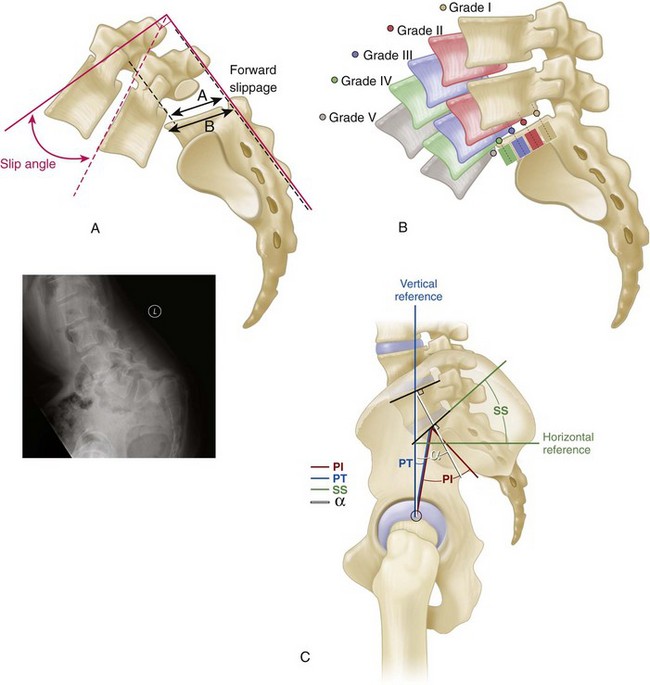

Severity—five grades according to severity (Meyerding); the severity of the slip is based on the amount or degree (compared with S1 width) (Figure 8-11)

Severity—five grades according to severity (Meyerding); the severity of the slip is based on the amount or degree (compared with S1 width) (Figure 8-11)

Other relevant measurements (see Figure 8-11)

Other relevant measurements (see Figure 8-11)

Sacral inclination (normally >30 degrees)

Sacral inclination (normally >30 degrees)

Slip angle (normally <0 degrees, signifying lordosis at the L5-S1 disc)

Slip angle (normally <0 degrees, signifying lordosis at the L5-S1 disc)

The natural history of the disorder is that unilateral pars defects almost never slip and that the progression of spondylolisthesis slows over time.

The natural history of the disorder is that unilateral pars defects almost never slip and that the progression of spondylolisthesis slows over time.

However, in adulthood, degeneration and narrowing of the disc (usually L5-S1) are common and lead to narrowing of the neural foramen and compression of the exiting (L5) root that causes the radicular symptoms.

However, in adulthood, degeneration and narrowing of the disc (usually L5-S1) are common and lead to narrowing of the neural foramen and compression of the exiting (L5) root that causes the radicular symptoms.

3. Childhood spondylolisthesis

Patients with a greater than 25% slip, or with L4-L5 or L3-L4 spondylolisthesis have a higher risk of low back pain than the general population.

Patients with a greater than 25% slip, or with L4-L5 or L3-L4 spondylolisthesis have a higher risk of low back pain than the general population.

Alteration in gait (“pelvic waddle”)

Alteration in gait (“pelvic waddle”)

Although symptoms may begin at any time in life, screening studies identify the slippage as occurring most commonly at age 4 to 6 years.

Although symptoms may begin at any time in life, screening studies identify the slippage as occurring most commonly at age 4 to 6 years.

Severe slips are rare and may be associated with radicular findings (L5), cauda equina dysfunction, kyphosis of the lumbosacral junction, and “heart-shaped” buttocks.

Severe slips are rare and may be associated with radicular findings (L5), cauda equina dysfunction, kyphosis of the lumbosacral junction, and “heart-shaped” buttocks.

Usually at L5-S1 and typically grade II

Usually at L5-S1 and typically grade II

Occurs most often in whites, boys, and children who participate in hyperextension activities

Occurs most often in whites, boys, and children who participate in hyperextension activities

It is thought to result from shear stress at the pars interarticularis and to be associated with repetitive hyperextension.

It is thought to result from shear stress at the pars interarticularis and to be associated with repetitive hyperextension.

Patients with type I or dysplastic spondylolisthesis are at a higher risk for slip progression and the development of cauda equina dysfunction because the neural arch is intact.

Patients with type I or dysplastic spondylolisthesis are at a higher risk for slip progression and the development of cauda equina dysfunction because the neural arch is intact.

Spina bifida occulta, thoracic hyperkyphosis, and Scheuermann disease have been associated with spondylolisthesis.

Spina bifida occulta, thoracic hyperkyphosis, and Scheuermann disease have been associated with spondylolisthesis.

Usually responds to nonoperative treatment consisting of activity modification and exercise

Usually responds to nonoperative treatment consisting of activity modification and exercise

Adolescents with a grade I slip may return to normal activities, including contact sports, once asymptomatic.

Adolescents with a grade I slip may return to normal activities, including contact sports, once asymptomatic.

Those with asymptomatic grade II spondylolisthesis are restricted from activities such as gymnastics or football.

Those with asymptomatic grade II spondylolisthesis are restricted from activities such as gymnastics or football.

Female gender, a slip angle of greater than 10 degrees

Female gender, a slip angle of greater than 10 degrees

Dome-shaped or significantly inclined sacrum (>30 degrees beyond vertical position)

Dome-shaped or significantly inclined sacrum (>30 degrees beyond vertical position)

Surgery for patients with a low-grade slip generally consists of L5-S1 posterolateral fusion in situ and is usually reserved for those with intractable pain in whom nonoperative treatment has failed or those demonstrating progressive slippage.

Surgery for patients with a low-grade slip generally consists of L5-S1 posterolateral fusion in situ and is usually reserved for those with intractable pain in whom nonoperative treatment has failed or those demonstrating progressive slippage.

Wiltse has popularized a paraspinal muscle–splitting approach to the lumbar transverse process and sacral alae that is frequently used in this setting.

Wiltse has popularized a paraspinal muscle–splitting approach to the lumbar transverse process and sacral alae that is frequently used in this setting.

L5 radiculopathy is uncommon in children with low-grade slips and rarely if ever requires decompression.

L5 radiculopathy is uncommon in children with low-grade slips and rarely if ever requires decompression.

Repair of the pars defect with the use of a lag screw (Buck) or tension band wiring (Bradford) with bone grafting has been reported.

Repair of the pars defect with the use of a lag screw (Buck) or tension band wiring (Bradford) with bone grafting has been reported.

High-grade disease (grades III through V)

High-grade disease (grades III through V)

These commonly cause neurologic abnormalities.

These commonly cause neurologic abnormalities.

L5-S1 isthmic spondylolisthesis causes an L5 radiculopathy (contrast to S1 radiculopathy in L5-S1 HNP).

L5-S1 isthmic spondylolisthesis causes an L5 radiculopathy (contrast to S1 radiculopathy in L5-S1 HNP).

Prophylactic fusion is recommended in growing children with slippage of more than 50%.

Prophylactic fusion is recommended in growing children with slippage of more than 50%.

It often requires in situ bilateral posterolateral fusion, usually at L4 to S1 (L5 is too far anterior to effect L5-S1 fusion) with or without instrumentation.

It often requires in situ bilateral posterolateral fusion, usually at L4 to S1 (L5 is too far anterior to effect L5-S1 fusion) with or without instrumentation.

Nerve root exploration is controversial but usually limited to children with clear-cut radicular pain or significant weakness.

Nerve root exploration is controversial but usually limited to children with clear-cut radicular pain or significant weakness.

Reduction of spondylolisthesis has been associated with a 20% to 30% incidence of L5 root injuries (most are transient) and should be used cautiously.

Reduction of spondylolisthesis has been associated with a 20% to 30% incidence of L5 root injuries (most are transient) and should be used cautiously.

A cosmetically unacceptable deformity and L5-S1 kyphosis so severe that the posterior fusion mass from L4 to the sacrum would be under tension without reversal of the kyphosis are the most commonly cited indications.