Trauma*

section 1 Care of the Multiply Injured Patient

A Primary assessment—Assessment begins with the primary survey, which seeks to identify any life-threatening injuries. A rapid assessment of airway, breathing, and circulation (the ABCs) is performed.

1. The airway is often managed by intubation, especially in patients experiencing a great deal of pain or obtundation. The initial survey should include placement of intravenous lines and treatment of any life-threatening injuries that are encountered.

1. Aggressive fluid resuscitation should begin immediately in most cases with the placement of two large-bore intravenous cannulas.

2. Two liters of lactated Ringer solution or normal saline should be administered.

3. If the patient remains hemodynamically unstable after initial crystalloid infusion, begin infusion of blood products.

If a patient does not respond to 2 L of crystalloid, 2 units of packed red blood cells should be administered.

If a patient does not respond to 2 L of crystalloid, 2 units of packed red blood cells should be administered.

Patients become coagulopathic and, thus, require both fresh frozen plasma and platelets.

Patients become coagulopathic and, thus, require both fresh frozen plasma and platelets.

The amount administered is controversial.

The amount administered is controversial.

Recent literature supports administration of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets in a 1 : 1 : 1 ratio.

Recent literature supports administration of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets in a 1 : 1 : 1 ratio.

The most common complication of massive transfusion is a dilutional thrombocytopenia, followed by hypothermia and metabolic alkalosis.

The most common complication of massive transfusion is a dilutional thrombocytopenia, followed by hypothermia and metabolic alkalosis.

Increased citrate from packed red blood cells binds calcium directly and can cause hypocalcemia.

Increased citrate from packed red blood cells binds calcium directly and can cause hypocalcemia.

6. Hemodynamic instability may result from internal injury or fractures and is the most important consideration for the orthopaedic surgeon.

Once the airway and breathing are controlled, problems with circulation remain the biggest threat to life.

Once the airway and breathing are controlled, problems with circulation remain the biggest threat to life.

Rapid application of splints and reduction of fractures when possible can decrease bleeding and relieve pain.

Rapid application of splints and reduction of fractures when possible can decrease bleeding and relieve pain.

7. The end points of adequate resuscitation are not clear; use of hemodynamic parameters is inadequate.

Base deficit, as measured by lactate level, is a proxy for the amount of anaerobic metabolism by the body.

Base deficit, as measured by lactate level, is a proxy for the amount of anaerobic metabolism by the body.

Lactate levels are frequently used in trauma to guide the adequacy of resuscitation.

Lactate levels are frequently used in trauma to guide the adequacy of resuscitation.

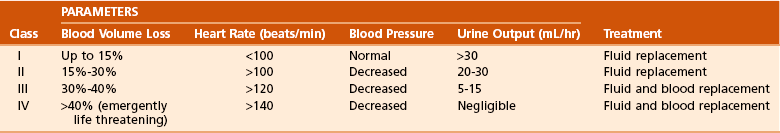

Table 11-1

Classification and Treatment of Hemorrhagic Shock

From Browner BD, on behalf of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma: Advanced trauma life support: skeletal trauma: basic science, management, and reconstruction, ed 8, Chicago, 2008, American College of Surgeons.

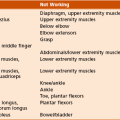

Due to a loss of sympathetic tone in setting of a spinal cord injury

Due to a loss of sympathetic tone in setting of a spinal cord injury

Presents as low heart rate, low blood pressure, and warm skin

Presents as low heart rate, low blood pressure, and warm skin

9. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is a generalized response to trauma characterized by an increase in cytokines, complement, and many hormones. These changes are seen in varying degrees after trauma, and there is probably a genetic predisposition to an intense form of these changes. Patients are considered to have SIRS if they have two or more of the following criteria:

Heart rate greater than 90 beats per minute

Heart rate greater than 90 beats per minute

White blood cell count (WBC) less than 4/mm3 or greater than 10/mm3

White blood cell count (WBC) less than 4/mm3 or greater than 10/mm3

Respiration greater than 20 breaths per minute, with Paco2 less than 32 mm

Respiration greater than 20 breaths per minute, with Paco2 less than 32 mm

10. SIRS is associated with disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), renal failure, shock, and multisystem organ failure.

1. A rapid radiologic workup that includes at a minimum anteroposterior (AP) chest, AP pelvis, and lateral cervical spine views is standard.

2. Availability and increased processing speed of computed tomographic (CT) scanners is leading to CT of cervical spine replacing lateral cervical spine radiography for trauma evaluation.

3. Care should be taken not to focus on obvious radiographic findings, such as an open-book pelvic injury, and miss other important findings, such as a widened mediastinum.

4. Pelvic fractures can be life threatening. The orthopaedic surgeon may be called on to stabilize pelvic fractures in the emergency department and should be prepared to place a pelvic binder or sheet.

5. Pelvic bleeding that does not respond rapidly to pelvic compression with a sheet or binder should be evaluated by angiography and embolization, if indicated.

D Trauma scoring systems—Numerous scoring systems seek to quantify the injury that a patient sustained (Tables 11-2 through 11-4). Although some may yield prognostic value, none is perfect. Therefore, a thorough workup is needed to identify all injuries and prioritize their management. Although it may be desirable to repair all fractures on the day of admission, it may be inherently dangerous to do so because of hemodynamic instability and the added trauma that surgery creates.

Table 11-2

| Response to Assessment | Score |

| Best Motor Response | |

| Obeys commands | 6 |

| Localizes pain | 5 |

| Normal withdrawal (flexion) | 4 |

| Abnormal withdrawal (flexion)—decorticate | 3 |

| Extension—decerebrate | 2 |

| None (flaccid) | 1 |

| Verbal Response | |

| Oriented | 5 |

| Confused conversation | 4 |

| Inappropriate words | 3 |

| Incomprehensible sounds | 2 |

| None | 1 |

| Eye Opening | |

| Spontaneous | 4 |

| To speech | 3 |

| To pain | 2 |

| None | 1 |

Table 11-3

| Examples of Abbreviated Injury Score | Score |

| Head | |

| Crush of head or brain | 6 |

| Brainstem contusion | 5 |

| Epidural hematoma (small) | 4 |

| Face | |

| Optic nerve laceration | 2 |

| External carotid laceration (major) | 3 |

| Le Fort III fracture | 3 |

| Neck | |

| Crushed larynx | 5 |

| Pharynx hematoma | 3 |

| Thyroid gland contusion | 1 |

| Thorax | |

| Open chest wound | 4 |

| Aorta, intimal tear | 4 |

| Esophageal contusion | 2 |

| Myocardial contusion | 3 |

| Pulmonary contusion (bilateral) | 4 |

| Two or three rib fractures | 2 |

| Abdominal and Pelvic Contents | |

| Bladder perforation | 4 |

| Colon transaction | 4 |

| Liver laceration with >20% blood loss | 3 |

| Retroperitoneal hematoma | 3 |

| Splenic laceration—major | 4 |

| Spine | |

| Incomplete brachial plexus | 2 |

| Complete spinal cord, C4 or below | 5 |

| Herniated disc with radiculopathy | 3 |

| Vertebral body compression >20% | 3 |

| Upper Extremity | |

| Amputation | 3 |

| Elbow crush | 3 |

| Shoulder dislocation | 2 |

| Open forearm fracture | 3 |

| Lower Extremity | |

| Amputation | |

| Below knee | 3 |

| Above knee | 4 |

| Hip dislocation | 2 |

| Knee dislocation | 2 |

| Femoral shaft fracture | 3 |

| Open pelvic fracture | 3 |

| External | |

| Hypothermia 31° to 30° C | 3 |

| Electrical injury with myonecrosis | 3 |

| Second- to third-degree burns—20%-29% of body surface area | 3 |

From Browner BD, et al, editors: Skeletal trauma, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2003, WB Saunders, p 135.

Table 11-4

Variables for the Mangled Extremity Severity Score

| Component | Points |

| Skeletal and Soft Tissue Injury | |

| Low energy (stab, simple fracture, “civilian” gunshot wound) | 1 |

| Medium energy (open or multiplex fractures, dislocation) | 2 |

| High energy (close-range shotgun or “military” gunshot wound, crush injury) | 3 |

| Very high energy (same as above, plus gross contamination, soft tissue avulsion) | 4 |

| Limb Ischemia (score is doubled for ischemia >6 hr) | |

| Pulse reduced or absent but perfusion normal | 1 |

| Pulseless, paresthesias, diminished capillary refill | 2 |

| Cool, paralyzed, insensate (numb) | 3 |

| Shock | |

| Systolic blood pressure always >90 mm Hg | 0 |

| Transient hypotension | 1 |

| Persistent hypotension | 2 |

| Age (yr) | |

| <30 | 0 |

| 30-50 | 1 |

| >50 | 2 |

From Johansen K, et al: Objective criteria accurately predict amputation following lower extremity trauma, J Trauma 30:568, 1990.

E Damage-control orthopaedics—Principles of damage control have been applied to orthopaedic surgery and are now widely accepted. Damage-control orthopaedics involves staging the definitive care of the patient to avoid adding to the overall trauma that the patient has undergone.

1. Trauma is associated with a surge in inflammatory mediators, which peak 2 to 5 days after trauma.

2. After the initial burst of cytokines and other mediators, leukocytes are “primed” and can be activated easily with further trauma, such as surgery. This may lead to multisystem organ failure or ARDS.

3. To minimize the additional trauma that is added with surgery, traumatologists will often treat only potentially life-threatening injuries during this acute inflammatory window.

4. In the severely injured polytrauma patient or one with significant chest trauma, only emergent and urgent conditions should be treated.

Compartment syndrome, fractures associated with vascular injury, unreduced dislocations, long bone fractures, open fractures, or unstable spine fractures should be stabilized acutely.

Compartment syndrome, fractures associated with vascular injury, unreduced dislocations, long bone fractures, open fractures, or unstable spine fractures should be stabilized acutely.

5. Acute stabilization is achieved primarily via external fixation.

Femur fractures may be converted from an external fixator to an intramedullary (IM) nail within 3 weeks.

Femur fractures may be converted from an external fixator to an intramedullary (IM) nail within 3 weeks.

Tibia fractures should be converted within 7 to 10 days. If longer periods of time are necessary, a staged removal of the external fixator and subsequent nailing several days later is recommended.

Tibia fractures should be converted within 7 to 10 days. If longer periods of time are necessary, a staged removal of the external fixator and subsequent nailing several days later is recommended.

6. The definitive treatment of pelvic and acetabular fractures is usually delayed for 7 to 10 days in polytrauma patients to allow consolidation of the pelvic hematoma and resolution of the acute inflammatory response.

II CARE OF INJURIES TO SPECIFIC TISSUES

1. Vascular injury—may be due to penetrating or blunt trauma

Diagnosis—The orthopaedic surgeon should recognize the injury and refer the patient to a vascular surgery specialist or a microsurgeon, as indicated.

Diagnosis—The orthopaedic surgeon should recognize the injury and refer the patient to a vascular surgery specialist or a microsurgeon, as indicated.

Vascular injury can be present when pulses are palpable, and a change in pulse or a difference from the contralateral side may be the only harbinger of a serious vascular injury.

Vascular injury can be present when pulses are palpable, and a change in pulse or a difference from the contralateral side may be the only harbinger of a serious vascular injury.

If pulses are not equal to the uninjured side, a workup is indicated.

If pulses are not equal to the uninjured side, a workup is indicated.

Vascular compromise may develop over the course of hours in the case of knee dislocations and must be recognized promptly.

Vascular compromise may develop over the course of hours in the case of knee dislocations and must be recognized promptly.

Treatment—Reduction of fractures will often restore vascularity in the case of long bone fractures.

Treatment—Reduction of fractures will often restore vascularity in the case of long bone fractures.

Diagnosis—One of the most frequently missed complications of trauma, this results when intracompartmental pressure exceeds capillary pressure, thus preventing exchange of waste and nutrients across vessel walls.

Diagnosis—One of the most frequently missed complications of trauma, this results when intracompartmental pressure exceeds capillary pressure, thus preventing exchange of waste and nutrients across vessel walls.

Unless it is treated within 4 to 6 hours, permanent injury will ensue. The diagnosis is clinical or made using a pressure monitor.

Unless it is treated within 4 to 6 hours, permanent injury will ensue. The diagnosis is clinical or made using a pressure monitor.

Clinical hallmarks are pain out of proportion to the injury and pain with passive stretching of the muscle.

Clinical hallmarks are pain out of proportion to the injury and pain with passive stretching of the muscle.

Intracompartmental pressure measurement is abnormal if pressure is within 30 mm of the diastolic pressure (ΔP) or greater than 30 mm of the absolute pressure (the criteria are debated).

Intracompartmental pressure measurement is abnormal if pressure is within 30 mm of the diastolic pressure (ΔP) or greater than 30 mm of the absolute pressure (the criteria are debated).

Intraoperative diastolic blood pressure during anesthesia is approximately 18 mm Hg lower than “baseline,” potentially giving spurious ΔP values.

Intraoperative diastolic blood pressure during anesthesia is approximately 18 mm Hg lower than “baseline,” potentially giving spurious ΔP values.

Treatment—Treatment is emergent decompression via fasciotomy.

Treatment—Treatment is emergent decompression via fasciotomy.

Sequelae—Sequelae are common and include claw toes and contractures in the hand.

Sequelae—Sequelae are common and include claw toes and contractures in the hand.

The most common form is nerve palsy (neurapraxia) caused by stretching of the nerve, which will recover over time (1 mm/day).

The most common form is nerve palsy (neurapraxia) caused by stretching of the nerve, which will recover over time (1 mm/day).

Tend to occur in certain regions of the United States. Envenomation occurs in only 25% of cases. Venom may be neurotoxic (coral snakes) or hemotoxic (rattlesnake, cottonmouth).

Tend to occur in certain regions of the United States. Envenomation occurs in only 25% of cases. Venom may be neurotoxic (coral snakes) or hemotoxic (rattlesnake, cottonmouth).

Treatment and complications—Treatment is symptomatic and expectant: antivenom in a monitored setting, débridement of necrotic tissue, and fasciotomy. Antivenom is available for all endemic snakes, but there is a high incidence of anaphylaxis or serum sickness associated with its use.

Treatment and complications—Treatment is symptomatic and expectant: antivenom in a monitored setting, débridement of necrotic tissue, and fasciotomy. Antivenom is available for all endemic snakes, but there is a high incidence of anaphylaxis or serum sickness associated with its use.

Cause—Injury is caused by ice crystals forming outside the cell(s).

Cause—Injury is caused by ice crystals forming outside the cell(s).

Treatment—Rapid rewarming and attention to arrhythmias are the current treatments. Amputation may be necessary.

Treatment—Rapid rewarming and attention to arrhythmias are the current treatments. Amputation may be necessary.

Burns—generally treated by burn surgeons, but extremity burns may be treated by orthopaedic surgeons. Débridement of deep dermal burns and skin grafting are the hallmarks of treatment after early, aggressive fluid resuscitation. Antibiotic prophylaxis and tetanus are routine.

Burns—generally treated by burn surgeons, but extremity burns may be treated by orthopaedic surgeons. Débridement of deep dermal burns and skin grafting are the hallmarks of treatment after early, aggressive fluid resuscitation. Antibiotic prophylaxis and tetanus are routine.

6. Electrical injury—may cause bone necrosis and massive soft tissue necrosis. The extent of tissue injury may not be apparent for days after injury because the skin may not be broken despite significant injury underneath.

Treatment is similar to that of burns; débridement followed by reconstruction with amputation, a flap, or a skin graft is required.

Treatment is similar to that of burns; débridement followed by reconstruction with amputation, a flap, or a skin graft is required.

7. Chemical burns—The first rule is to avoid contamination from other people and further damage to the victim.

Dilution with copious irrigation is the initial treatment. After initial irrigation, the degree of necrosis is assessed, with débridement of necrotic tissue. Hydrofluoric acid is extremely toxic, causing profound hypocalcemia and cardiac death with little exposure; calcium gluconate may be used to treat skin exposure.

Dilution with copious irrigation is the initial treatment. After initial irrigation, the degree of necrosis is assessed, with débridement of necrotic tissue. Hydrofluoric acid is extremely toxic, causing profound hypocalcemia and cardiac death with little exposure; calcium gluconate may be used to treat skin exposure.

8. High-pressure injury (water, paint, grease)—Hand injuries are the most common. There may be extensive damage to underlying soft tissues despite a small entrance wound. Wide débridement of necrotic tissue and foreign material is required.

B Joint injuries—Joint injuries may be caused by penetrating or blunt trauma.

1. Dislocations—These orthopaedic emergencies should be reduced as soon as possible to avoid injury to the nerve and vessels and the articular cartilage; general anesthesia may be needed. Neurovascular status should be assessed and documented both before and after reduction.

Antibiotics—Penetrating trauma such as gunshot wounds may be treated with oral antibiotics if there is no debris in the joint; however, foreign matter is often carried into the joint as it is penetrated, even in “clean” gunshot wounds.

Antibiotics—Penetrating trauma such as gunshot wounds may be treated with oral antibiotics if there is no debris in the joint; however, foreign matter is often carried into the joint as it is penetrated, even in “clean” gunshot wounds.

3. Fractures involving the joints—must be reduced as anatomically as possible to reduce unequal wear

Classification—The Gustillo and Anderson grading system is widely used (Table 11-5). There is considerable interobserver variability, and the type may change with time.

Classification—The Gustillo and Anderson grading system is widely used (Table 11-5). There is considerable interobserver variability, and the type may change with time.

Table 11-5

Classification of Open Fractures

| Fracture Type | Description |

| I | Skin opening of ≤1 cm, quite clean; most likely from inside to outside; minimum muscle contusion; simple transverse or short oblique fractures |

| II | Laceration >1 cm long, with extensive soft tissue damage, flaps, or avulsion; minimum to moderate crushing component; simple transverse or short oblique fractures with minimum comminution |

| III | Extensive soft tissue damage, including muscles, skin, and neurovascular structures; often a high-velocity injury with severe crushing component |

| IIIA | Extensive soft tissue laceration, adequate bone coverage; segmental fractures, gunshot injuries |

| IIIB | Extensive soft tissue injury, with periosteal stripping and bone exposure; usually associated with massive contamination; requires soft tissue coverage |

| IIIC | Vascular injury requiring repair |

From Gustilo RB, Mendoza RM, Williams DN: Problems in the management of type III (severe) open fractures: a new classification of type III open fractures, J Trauma 24:742, 1984.

Type I—no periosteal stripping, minimum soft tissue damage, small skin wound (1 cm)

Type I—no periosteal stripping, minimum soft tissue damage, small skin wound (1 cm)

Type II—little periosteal stripping, moderate muscle damage, skin wound (1-10 cm)

Type II—little periosteal stripping, moderate muscle damage, skin wound (1-10 cm)

Type IIIA—contaminated wound (high-energy gunshot wound, farm injury, shotgun) or extensive periosteal stripping with large skin wound (>10 cm)

Type IIIA—contaminated wound (high-energy gunshot wound, farm injury, shotgun) or extensive periosteal stripping with large skin wound (>10 cm)

Type IIIB—same as IIIA but will require flap coverage

Type IIIB—same as IIIA but will require flap coverage

Type IIIC—same as IIIA but with vascular injury that requires repair

Type IIIC—same as IIIA but with vascular injury that requires repair

Débridement—Initial treatment should consist of local wound débridement that is adequate to clean the wound and débridement of all necrotic tissue.

Débridement—Initial treatment should consist of local wound débridement that is adequate to clean the wound and débridement of all necrotic tissue.

Antibiotics—usually started immediately. Antibiotic bead pouch with methylmethacrylate, tobramycin, and/or vancomycin may be used to temporize dirty wounds.

Antibiotics—usually started immediately. Antibiotic bead pouch with methylmethacrylate, tobramycin, and/or vancomycin may be used to temporize dirty wounds.

Types I and II—first-generation cephalosporin (cefazolin) for 24 hours

Types I and II—first-generation cephalosporin (cefazolin) for 24 hours

Type III—cephalosporin and aminoglycoside for 72 hours after last incision and drainage

Type III—cephalosporin and aminoglycoside for 72 hours after last incision and drainage

Heavily contaminated wounds and farm wounds—cephalosporin, aminoglycosides, and high-dose penicillin

Heavily contaminated wounds and farm wounds—cephalosporin, aminoglycosides, and high-dose penicillin

Fresh water wounds—fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin) or third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin (ceftazidime)

Fresh water wounds—fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin) or third- or fourth-generation cephalosporin (ceftazidime)

Salt water wounds—doxycycline and ceftazidime or a fluoroquinolone

Salt water wounds—doxycycline and ceftazidime or a fluoroquinolone

Stabilization of bony injuries—will decrease further damage to soft tissue

Stabilization of bony injuries—will decrease further damage to soft tissue

Early coverage (<5 days is the goal). However, zone of injury must be well defined before coverage.

Early coverage (<5 days is the goal). However, zone of injury must be well defined before coverage.

Gastrocnemius flap—for proximal third tibial fractures

Gastrocnemius flap—for proximal third tibial fractures

Soleus flap—for middle third tibial fractures

Soleus flap—for middle third tibial fractures

Fasciocutaneous flap or free-tissue transfer—for distal third fractures

Fasciocutaneous flap or free-tissue transfer—for distal third fractures

Negative-pressure therapy is commonly used to treat wounds but is not a substitute for definitive coverage.

Negative-pressure therapy is commonly used to treat wounds but is not a substitute for definitive coverage.

2. Stabilization with external fixation

Immediate treatment—Most fractures should be reduced and splinted promptly to avoid further soft tissue damage. External fixation may be used to treat grossly contaminated wounds and fractures that will require time for the soft tissues to heal before definitive fixation.

Immediate treatment—Most fractures should be reduced and splinted promptly to avoid further soft tissue damage. External fixation may be used to treat grossly contaminated wounds and fractures that will require time for the soft tissues to heal before definitive fixation.

Definitive treatment—External fixation may be used definitively for periarticular fractures, articular fractures that cannot be reconstructed, and segmental fractures, but internal fixation is far more common.

Definitive treatment—External fixation may be used definitively for periarticular fractures, articular fractures that cannot be reconstructed, and segmental fractures, but internal fixation is far more common.

3. Perioperative complications

Thromboembolic disease—The incidence is very high in pelvic, spine, hip, and lower extremity fractures. Pulmonary embolus develops in as many as 5% of those who have deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

Thromboembolic disease—The incidence is very high in pelvic, spine, hip, and lower extremity fractures. Pulmonary embolus develops in as many as 5% of those who have deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

Diagnosis—Diagnosis of DVT is by Doppler ultrasound, magnetic resonance venography, or d-dimer titers

Diagnosis—Diagnosis of DVT is by Doppler ultrasound, magnetic resonance venography, or d-dimer titers

Treatment—All patients with these injuries should receive some form of thromboembolic disease prophylaxis (mechanical or pharmacologic). The risks of pharmacologic prophylaxis include prolonged bleeding from surgical or traumatic wounds or a cerebral bleed.

Treatment—All patients with these injuries should receive some form of thromboembolic disease prophylaxis (mechanical or pharmacologic). The risks of pharmacologic prophylaxis include prolonged bleeding from surgical or traumatic wounds or a cerebral bleed.

Fat embolus syndrome—associated with reaming of long bones but can occur with any long bone fracture. Hypoxia, a petechial rash on the chest, and tachycardia are the hallmarks. Treatment is supportive.

Fat embolus syndrome—associated with reaming of long bones but can occur with any long bone fracture. Hypoxia, a petechial rash on the chest, and tachycardia are the hallmarks. Treatment is supportive.

ARDS—Patients with chest trauma and multiple fractures are at high risk. It is unclear whether reamed nailing of long bone fractures causes it directly but may be implicated in the “second hit” phenomenon. Treatment is supportive (O2, ventilator).

ARDS—Patients with chest trauma and multiple fractures are at high risk. It is unclear whether reamed nailing of long bone fractures causes it directly but may be implicated in the “second hit” phenomenon. Treatment is supportive (O2, ventilator).

Delayed union—defined as no progression of healing over serial radiographs. Treatment may include bone grafting and external bone stimulation.

Delayed union—defined as no progression of healing over serial radiographs. Treatment may include bone grafting and external bone stimulation.

Biologic treatments—many new treatments, but scanty literature to support any one over the others

Biologic treatments—many new treatments, but scanty literature to support any one over the others

Calcium sulfate—short resorption time

Calcium sulfate—short resorption time

Calcium phosphate—very long resorption time

Calcium phosphate—very long resorption time

Bone morphogenetic protein—expensive, indicated in some acute tibia fractures, and possibly useful in nonunions

Bone morphogenetic protein—expensive, indicated in some acute tibia fractures, and possibly useful in nonunions

Platelet-derived growth factors—seek to add osteoinductive factors to an osteoconductive matrix (cancellous bone, calcium)

Platelet-derived growth factors—seek to add osteoinductive factors to an osteoconductive matrix (cancellous bone, calcium)

Identify infection and treat appropriately.

Identify infection and treat appropriately.

Bone stimulator—no strong evidence for effectiveness of one method over the other

Bone stimulator—no strong evidence for effectiveness of one method over the other

Segmental bone loss—Treatment includes treatment with bone graft, interposition free tissue transfer (free-fibula transfer), bone transport (Ilizarov or Taylor spatial frame), and amputation.

Segmental bone loss—Treatment includes treatment with bone graft, interposition free tissue transfer (free-fibula transfer), bone transport (Ilizarov or Taylor spatial frame), and amputation.

Diagnosis—common in head-injured patients and in hip, elbow, and shoulder fractures. Any fracture associated with extensive muscle damage is at risk.

Diagnosis—common in head-injured patients and in hip, elbow, and shoulder fractures. Any fracture associated with extensive muscle damage is at risk.

Prophylaxis—Indomethacin 25 mg orally three times a day or indomethacin (sustained release) 75 mg orally daily for 6 weeks may be effective in preventing heterotopic bone formation.

Prophylaxis—Indomethacin 25 mg orally three times a day or indomethacin (sustained release) 75 mg orally daily for 6 weeks may be effective in preventing heterotopic bone formation.

Radiation therapy (600-700 cGy) given 24 hours before or up to 72 hours after surgery; equal to indomethacin in effectiveness (but no issues with compliance with medication regimen)

Radiation therapy (600-700 cGy) given 24 hours before or up to 72 hours after surgery; equal to indomethacin in effectiveness (but no issues with compliance with medication regimen)

Treatment—early, active range of motion (ROM) for the elbow and shoulder. Excision of problematic heterotopic ossification can be considered when no further growth (controversial how to assess—“quiet” bone scan, stable disease shown on radiographs, time >1 year)

Treatment—early, active range of motion (ROM) for the elbow and shoulder. Excision of problematic heterotopic ossification can be considered when no further growth (controversial how to assess—“quiet” bone scan, stable disease shown on radiographs, time >1 year)

Definitive diagnosis—by bone biopsy

Definitive diagnosis—by bone biopsy

Other tests—may be used in combination with physical examination (draining wound, pain) to confirm the diagnosis

Other tests—may be used in combination with physical examination (draining wound, pain) to confirm the diagnosis

Treatment—based on grade and host type (Cierny/Mader)

Treatment—based on grade and host type (Cierny/Mader)

Grade I—IM nail removal and reaming

Grade I—IM nail removal and reaming

Grade II—superficial; involves cortex; often seen in diabetic wounds; curettage

Grade II—superficial; involves cortex; often seen in diabetic wounds; curettage

Grade III—localized; involves cortical lesion, with extension into medullary canal; requires wide excision, bone grafting, and perhaps stabilization

Grade III—localized; involves cortical lesion, with extension into medullary canal; requires wide excision, bone grafting, and perhaps stabilization

Grade IV—diffuse; indicates spread through cortex and along medullary canal; wide sequestrectomy, muscle flap, bone graft, and stabilization

Grade IV—diffuse; indicates spread through cortex and along medullary canal; wide sequestrectomy, muscle flap, bone graft, and stabilization

Fractures caused by gunshot wounds

Fractures caused by gunshot wounds

High-energy gunshot and shotgun wounds—These are considered grade III open fractures because they are often associated with considerable soft tissue injury (Table 11-6). They require extensive surgical débridement of necrotic tissue and require surgical stabilization of the fracture.

High-energy gunshot and shotgun wounds—These are considered grade III open fractures because they are often associated with considerable soft tissue injury (Table 11-6). They require extensive surgical débridement of necrotic tissue and require surgical stabilization of the fracture.

Table 11-6

Classification of Closed Fractures with Soft Tissue Damage

| Fracture Type | Description |

| 0 | Minimum soft tissue damage; indirect violence; simple fracture patterns Example: torsion fracture of the tibia in skiers |

| I | Superficial abrasion or contusion caused by pressure from within; mild to moderately severe fracture configuration Example: pronation fracture-dislocation of the ankle joint with soft tissue lesion over the medial malleolus |

| II | Deep, contaminated abrasion associated with localized skin or muscle contusion; impending compartment syndrome; severe fracture configuration Example: segmental “bumper” fracture of the tibia |

| III | Extensive skin contusion or crush injury; underlying muscle damage may be severe; subcutaneous avulsion; decompensated compartment syndrome; associated major vascular injury; severe or comminuted fracture configuration |

From Tscherne H, Oestern HJ: Die Klassifizierung des Weichteilschadens bei offenen und geschlossenen Frakturen, Unfallheilkunde 85:111-115, 1982. © Springer-Verlag.

Low-energy gunshot wounds—can be treated as a closed fracture but should get single-dose, first-generation cephalosporin and local wound care

Low-energy gunshot wounds—can be treated as a closed fracture but should get single-dose, first-generation cephalosporin and local wound care

Bullets that pass through colon—may contaminate any fracture caused by the bullet after perforation (pelvis, spine). Bony fractures may be managed with antibiotics alone if extraarticular and the fracture pattern is stable.

Bullets that pass through colon—may contaminate any fracture caused by the bullet after perforation (pelvis, spine). Bony fractures may be managed with antibiotics alone if extraarticular and the fracture pattern is stable.

III BIOMECHANICS OF FRACTURE HEALING

Also see Chapter 1, Biomechanics

A Stability and fracture healing

1. Micromotion at fracture site under physiologic load leads to callus formation.

2. Strain decreases as callus matures, leading to increased stability.

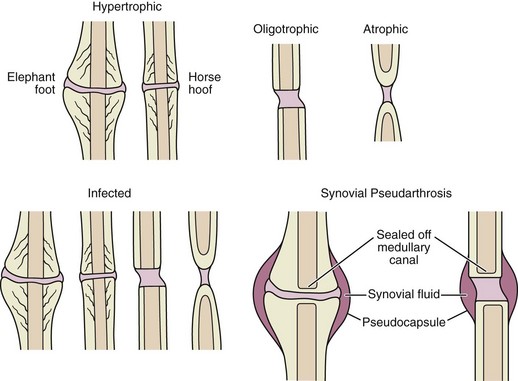

3. If there is too much motion, callus becomes hypertrophic as it tries to spread out force and hypertrophic nonunion can result.

4. Examples: casts, external fixators, IM nails, bridge plates

1. No motion at fracture site under physiologic load

2. Bone heals through direct healing (no callus).

2. Healing times are longer and more difficult to confirm on by radiography.

5. Implants must have longer fatigue life.

6. Examples: lag screws, compression plating, rigid locked plating (in nonbridging mode)

Also see Chapter 1, Biomechanics

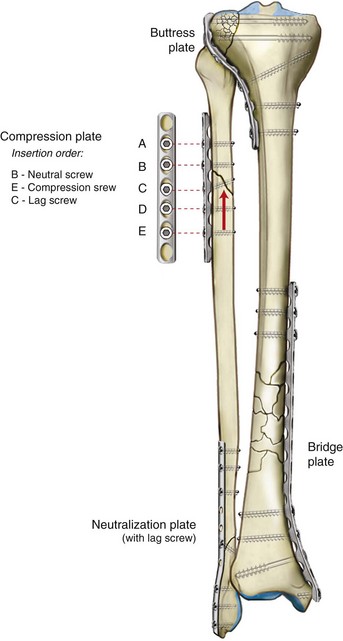

1. Provide rigid interfragmentary compression (absolute stability)

2. Force is concentrated over a small area (around the screw) so typically a plate is needed to protect/neutralize the deforming forces.

1. Compress plate to bone but will not provide interfragmentary compression

2. Friction between screw, plate, and bone resists pullout or bending.

1. Plate length matters more for bending stability than number of screws in plate.

2. Torsional stability is more affected by position of screws (need end hole filled).

3. Longer plates spread the strain over more area (working length).

4. Plates are load bearing—will stress shield area covered by plate; important to protect area temporarily if plate removed after healing

1. Plate design (oval holes) or use of compression device allows plate to apply compressive forces across fracture.

2. Provides absolute stability when properly applied

3. Relies on friction between plate and bone (needs at least some nonlocking screws)

4. May need pre-bend to eliminate gapping opposite plate

5. Insertion order is neutral position, then compression on opposite side of fracture, then lag screw (if placing through plate).

6. Tight contact of plate to bone when initially applied causes decreased periosteal blood flow and temporary osteopenia.

1. Primarily for comminuted fracture patterns

2. Plate “bridges” area of comminution with fixation above and below fracture.

3. Allows some elastic deformation (relative stability)

4. Avoid use of screws too close to fracture.

5. Number and types of screws to insert are fracture dependent—no clear, widely accepted guidelines.

6. Nonlocking screws compress plate to bone and can be used to lag in fragments; locking screws provide angular stability in short metaphyseal segments or in osteoporotic bone.

1. Provides support at 90-degree angle to fracture—typically in depressed metaphyseal/articular fractures that have been reduced

G Submuscular/percutaneous plating

1. To preserve biology at fracture site, plate may be placed in submuscular plane by sliding through small incisions proximal or distal to fracture and avoiding exposure of fracture site.

2. Typically used in bridge mode, although not exclusive

3. Advantage is decreased soft tissue and biologic compromise.

1. Screws have threads in head, which lock into corresponding holes in the plate.

2. Does not depend on friction between plate and bone for stability

3. Provides fixed angle construct—similar to blade plate

4. Most useful in unstable, short-segment metaphyseal fractures and osteoporotic bone

5. Fractures in which locking plate use is supported by data include

Typically for metaphyseal bone

Typically for metaphyseal bone

Similar pullout strength to bicortical locked screws in good quality diaphyseal bone (but rare indications for use there)

Similar pullout strength to bicortical locked screws in good quality diaphyseal bone (but rare indications for use there)

7. Bicortical locked screws: biggest advantage is in osteoporotic, diaphyseal bone

9. “Hybridization” describes the use of both locking and nonlocking screws in combination. This allows for both compression and fixed-angle support.

1. Load-sharing devices—relative stability

3. Radius of curvature of femoral nails is typically less than anatomic, improving frictional fixation.

A large mismatch of curvature, however, results in difficult insertion, increased risk of intraoperative fracture, and malreduction in extension.

A large mismatch of curvature, however, results in difficult insertion, increased risk of intraoperative fracture, and malreduction in extension.

4. Nails resist bending very well and require interlocks to resist torsion or compression loads.

5. Working length is the portion of the nail that is unsupported by bone when loaded.

6. Advantage of intramedullary position is decreased lever arm for bending forces (especially useful in pertrochanteric fractures versus plate and screw construct).

section 2 Upper Extremity

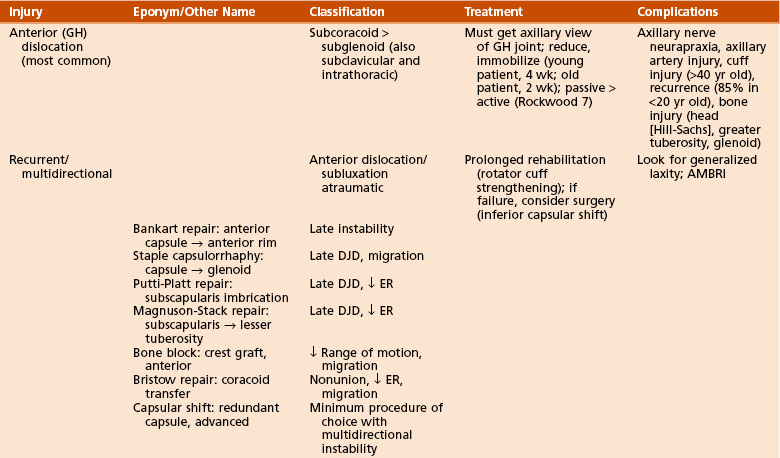

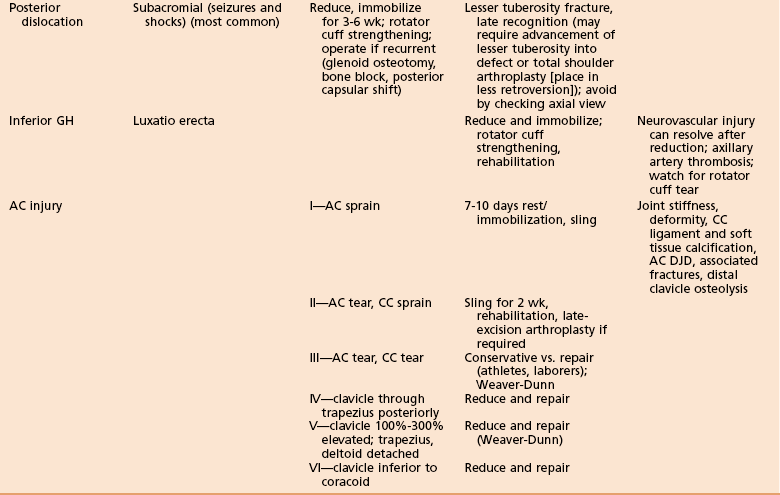

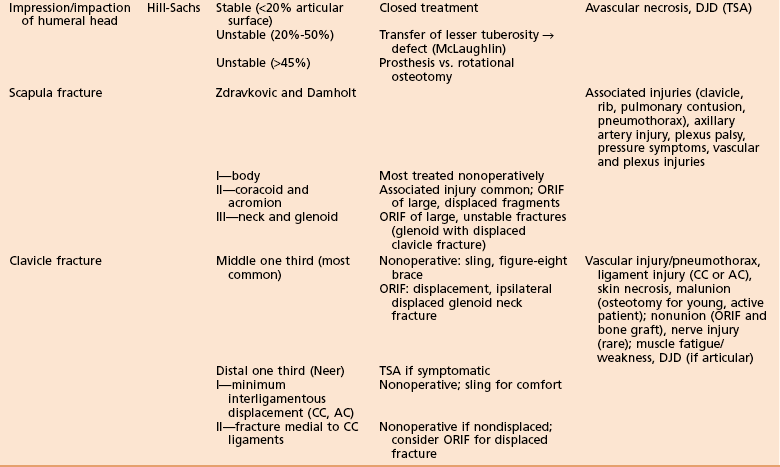

I SHOULDER INJURIES (Tables 11-7 and 11-8)

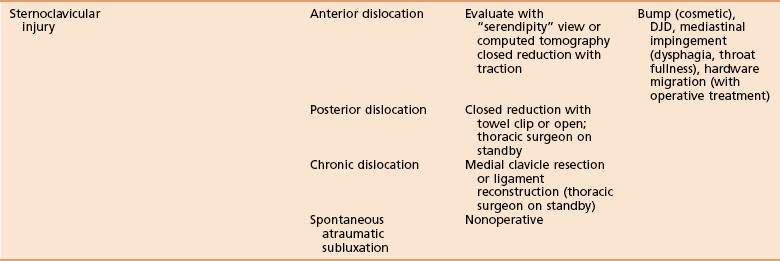

Table 11-8

A Sternoclavicular dislocation—“Serendipity” view or CT scan reveals dislocation of the sternoclavicular joint.

1. Anterior dislocation—more common, treated by closed reduction. The majority will remain unstable regardless of initial treatment modality, but these are typically asymptomatic.

2. Posterior dislocation—more serious—30% associated with significant compression of posterior structures. May cause dysphagia or difficulty breathing and sensation of fullness in the throat. Treated by closed reduction with a towel clip in the operating room. A thoracic surgeon should be on standby.

3. Chronic dislocation—treated by resection of the medial clavicle, with preservation and reconstruction of costoclavicular ligaments

4. Pseudodislocation—The medial clavicular epiphysis is the last to close at a mean age of 25 years. In patients younger than this, sternoclavicular dislocation is often a Salter-Harris type I or II fracture.

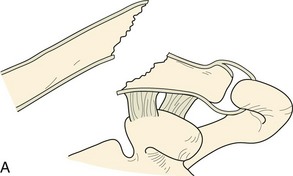

B Clavicle fracture (Figure 11-3, A and B)

1. Classification—classified by thirds

2. Diagnosis—AP and 15-degree cephalad-oblique radiographic views

3. Associated injuries—Open clavicle fractures are associated with high rates of pulmonary and closed-head injuries.

Nonoperative treatment—most mid-third fractures treated nonoperatively in a sling

Nonoperative treatment—most mid-third fractures treated nonoperatively in a sling

No difference in outcome between regular sling and figure-eight bandage

No difference in outcome between regular sling and figure-eight bandage

Risk of nonunion after midshaft fractures is higher in females and elderly and those fractures that are displaced, shortened more than 2 cm, or comminuted.

Risk of nonunion after midshaft fractures is higher in females and elderly and those fractures that are displaced, shortened more than 2 cm, or comminuted.

Lateral fractures have higher rates of nonunion compared with midshaft fractures.

Lateral fractures have higher rates of nonunion compared with midshaft fractures.

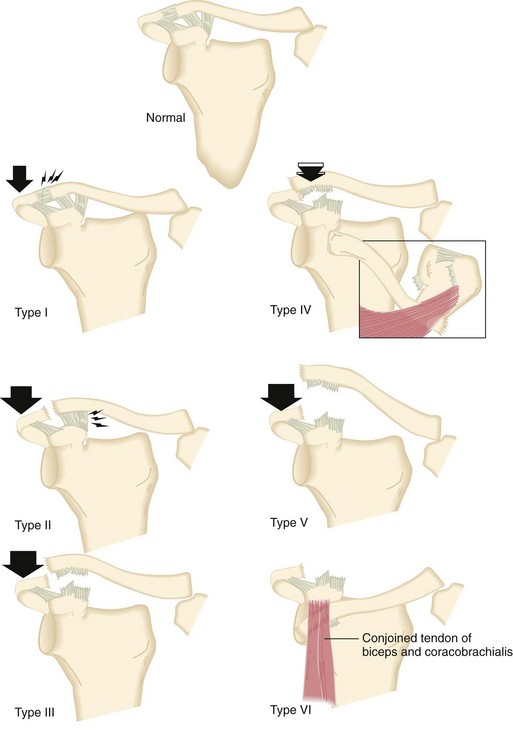

C Acromioclavicular dislocation

1. Classification—classified by extent of involvement of the ligamentous support and direction and magnitude of displacement (Figure 11-4). Coracoclavicular (CC) and acromioclavicular (AC) ligaments may be ruptured.

Type II—rupture of AC ligaments and sprain of CC ligaments

Type II—rupture of AC ligaments and sprain of CC ligaments

Type III—rupture of both AC and CC ligaments

Type III—rupture of both AC and CC ligaments

Type IV—The clavicle is buttonholed through the trapezius posteriorly.

Type IV—The clavicle is buttonholed through the trapezius posteriorly.

D Scapula fracture—associated with pulmonary contusion, pneumothorax, clavicle fracture (i.e., floating shoulder), rib fracture, head injury, brachial plexus injury, upper extremity vascular injury, pelvic or acetabular fracture and spine fracture. Scapula body fractures are generally treated in a sling for 7 to 10 days and then with early ROM.

1. Nonoperative treatment—used for nondisplaced fractures

2. Operative treatment—indicated for intraarticular fractures that are displaced more than 2 mm or widely displaced extraarticular fractures. The approach is usually through a posterior portal, although the Neviaser portal may be used to place a superoinferior screw in the glenoid.

1. Nonoperative treatment—Many authors advocate nonoperative treatment in almost all cases.

2. Operative treatment—indicated when glenoid neck and humeral head are translocated anterior to the proximal fragment or are medially displaced. Reduction and plating is through a posterior approach between infraspinatus (suprascapular nerve) and teres minor (axillary nerve). The suprascapular nerve and artery are at risk from excessive superior retraction, whereas the circumflex scapular artery is at risk during the approach.

G Scapulothoracic dissociation—the result of significant trauma to the chest wall, lung, and heart. Severe cases are treated essentially with a closed forequarter amputation.

Subclavian or axillary artery injury

Subclavian or axillary artery injury

AC dislocation, clavicle fracture, and sternoclavicular dislocation

AC dislocation, clavicle fracture, and sternoclavicular dislocation

2. Diagnosis should be suspected when there is a neurologic and/or vascular deficit. Lateral displacement of the scapula more than 1 cm on a chest radiograph is also suggestive.

Hemodynamically stable—angiography before surgery. Vascular injury may potentially be treated nonoperatively owing to the extensive collateral network around the shoulder.

Hemodynamically stable—angiography before surgery. Vascular injury may potentially be treated nonoperatively owing to the extensive collateral network around the shoulder.

Hemodynamically unstable—high lateral thoracotomy or median sternotomy to control bleeding

Hemodynamically unstable—high lateral thoracotomy or median sternotomy to control bleeding

Musculoskeletal injury treatment is controversial but is often nonoperative if vascular repair is not undertaken.

Musculoskeletal injury treatment is controversial but is often nonoperative if vascular repair is not undertaken.

4. Functional outcome is based on severity of associated neurologic injury.

H Floating shoulder—fracture of the glenoid neck and clavicle

1. Some authors recommend fixation when a clavicle fracture is associated with a displaced glenoid neck fracture, whereas others do not consider it necessary (depends on stability of superior shoulder suspensory complex [SSSC]).

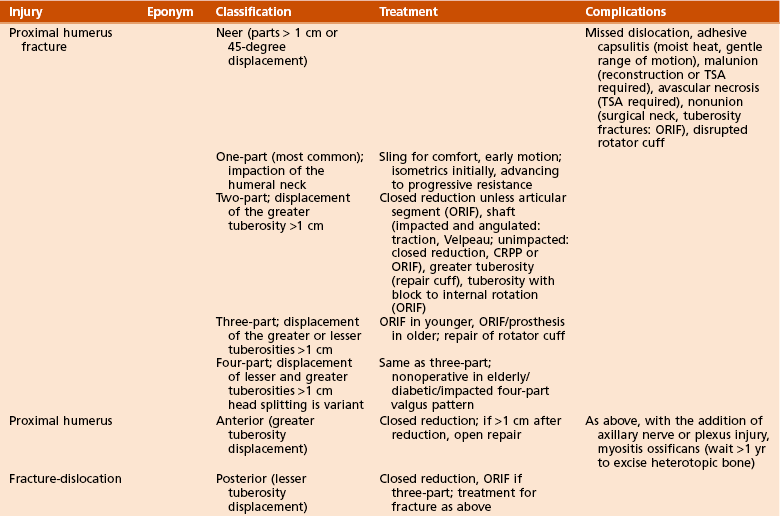

I Proximal humerus fracture (Figure 11-5)

1. Neer classification (“part” is defined as displacement of more than 1 cm or angulation of more than 45 degrees). Parts are articular surface, greater tuberosity, lesser tuberosity and shaft

One-part—nondisplaced or minimally displaced fracture (often of the humeral neck)

One-part—nondisplaced or minimally displaced fracture (often of the humeral neck)

Two-part—displacement of tuberosity of more than 1 cm; or surgical neck with head/shaft angled or displaced

Two-part—displacement of tuberosity of more than 1 cm; or surgical neck with head/shaft angled or displaced

Three-part—displacement of the greater or lesser tuberosities and articular surface

Three-part—displacement of the greater or lesser tuberosities and articular surface

Four-part—displacement of shaft, articular surface and both tuberosities. “Head splitting” is a variant, with split through the articular surface (usually requires replacement for treatment).

Four-part—displacement of shaft, articular surface and both tuberosities. “Head splitting” is a variant, with split through the articular surface (usually requires replacement for treatment).

One-part—sling for comfort and early mobilization

One-part—sling for comfort and early mobilization

Two-part—repair of the displaced tuberosity with sutures or tension band wiring; surgical neck fractures can normally be managed nonoperatively. Unstable, unimpacted fractures may be treated with closed reduction with percutaneous pinning (CRPP).

Two-part—repair of the displaced tuberosity with sutures or tension band wiring; surgical neck fractures can normally be managed nonoperatively. Unstable, unimpacted fractures may be treated with closed reduction with percutaneous pinning (CRPP).

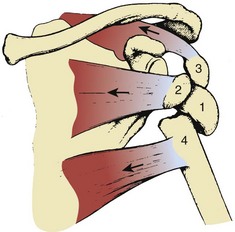

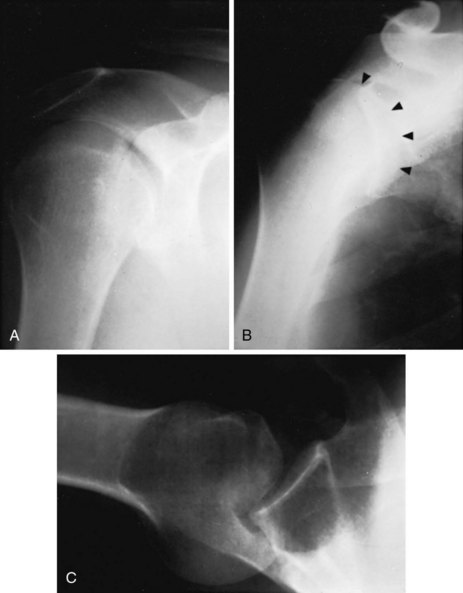

1. Anterior or anteroinferior (Figure 11-6) most common

Treatment—reduction (multiple maneuvers available)

Treatment—reduction (multiple maneuvers available)

Sling for 2 weeks in the elderly and 4 weeks in the young, followed by rotator cuff strengthening

Sling for 2 weeks in the elderly and 4 weeks in the young, followed by rotator cuff strengthening

Consider operative treatment in cases of recurrence or rotator cuff tear.

Consider operative treatment in cases of recurrence or rotator cuff tear.

The most common associated injury at arthroscopy after acute dislocation is anterior labral tear, followed by anterior capsular insufficiency and Hill-Sachs lesion.

The most common associated injury at arthroscopy after acute dislocation is anterior labral tear, followed by anterior capsular insufficiency and Hill-Sachs lesion.

High recurrence rate in young patients (owing to unstable labral tear)

High recurrence rate in young patients (owing to unstable labral tear)

High incidence of rotator cuff injury in older patients (>45 years)

High incidence of rotator cuff injury in older patients (>45 years)

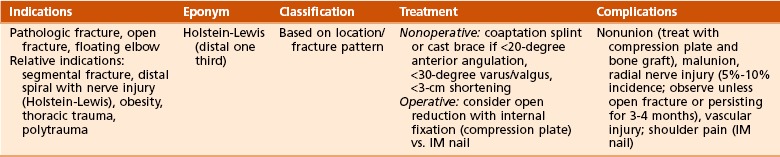

1. Classification—by location and fracture pattern

Nonoperative treatment—functional brace if there is less than 20 degrees of anterior angulation, less than 30 degrees of valgus/varus angulation, or less than 3 cm of shortening

Nonoperative treatment—functional brace if there is less than 20 degrees of anterior angulation, less than 30 degrees of valgus/varus angulation, or less than 3 cm of shortening

Operative treatment—open fracture, floating elbow, polytrauma, pathologic fracture, associated brachial plexus injury

Operative treatment—open fracture, floating elbow, polytrauma, pathologic fracture, associated brachial plexus injury

The vast majority (up to 92%) resolve with observation for 3 to 4 months.

The vast majority (up to 92%) resolve with observation for 3 to 4 months.

Brachioradialis followed by extensor carpi radialis longus are the first to return, whereas extensor pollicis longus and extensor indicis proprius are last to return.

Brachioradialis followed by extensor carpi radialis longus are the first to return, whereas extensor pollicis longus and extensor indicis proprius are last to return.

Controversial whether to observe or explore:

Controversial whether to observe or explore:

Secondary nerve palsy (i.e., after fracture manipulation)

Secondary nerve palsy (i.e., after fracture manipulation)

Spiral or oblique fracture of distal third (Holstein-Lewis fracture)

Spiral or oblique fracture of distal third (Holstein-Lewis fracture)

Management of palsy that does not recover is also controversial as to timing of electromyography, nerve exploration, and tendon transfers.

Management of palsy that does not recover is also controversial as to timing of electromyography, nerve exploration, and tendon transfers.

Nonunion—Treat with compression plate with bone graft if atrophic.

Nonunion—Treat with compression plate with bone graft if atrophic.

Shoulder pain—Some papers report a high incidence of shoulder pain, whereas others do not. Overall incidence is higher with IM nails.

Shoulder pain—Some papers report a high incidence of shoulder pain, whereas others do not. Overall incidence is higher with IM nails.

B Supracondylar fracture—rare injury in adults

3. Complications—neurovascular injury, nonunion, malunion, and loss of motion (contracture, fibrosis, bony block)

C Distal single-column (condyle) fracture

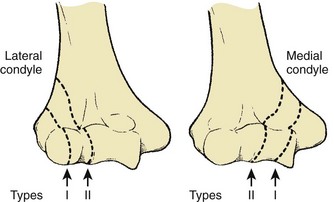

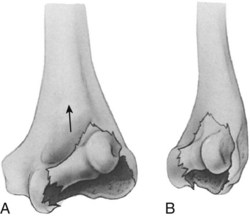

Classified as Milch types I and II lateral condyle fractures (more common) and types I and II medial condyle fractures. In type I lateral condyle fractures the lateral trochlear ridge is intact, and in type II lateral condyle fractures there is a fracture through lateral trochlear ridge (Figure 11-9).

Classified as Milch types I and II lateral condyle fractures (more common) and types I and II medial condyle fractures. In type I lateral condyle fractures the lateral trochlear ridge is intact, and in type II lateral condyle fractures there is a fracture through lateral trochlear ridge (Figure 11-9).

2. Treatment—type I nondisplaced: immobilize in supination (lateral condyle fracture) or pronation (medial condyle fracture); otherwise, CRPP or ORIF

3. Complications—cubitus valgus (lateral) or cubitus varus (medial), ulnar nerve injury, and degenerative joint disease (DJD)

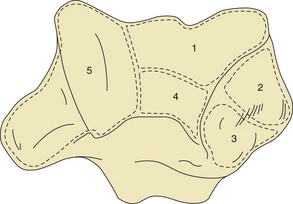

1. Presentation—Five major articular fragments are identified: capitellum/lateral trochlea, lateral epicondyle, posterolateral epicondyle, posterior trochlea, and medial trochlea/epicondyle (Figure 11-10)

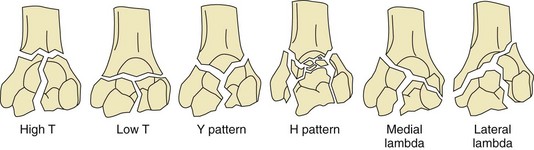

Jupiter classification (Figure 11-11)

Jupiter classification (Figure 11-11)

High T—proximal or at level of olecranon fossa

High T—proximal or at level of olecranon fossa

Low T (common)—transverse component just proximal to the trochlea

Low T (common)—transverse component just proximal to the trochlea

Y—oblique portion through both columns with distal vertical fracture

Y—oblique portion through both columns with distal vertical fracture

H—trochlea is free fragment (avascular necrosis [AVN])

H—trochlea is free fragment (avascular necrosis [AVN])

Medial lambda—proximal fracture exits medially

Medial lambda—proximal fracture exits medially

3. Treatment (goal is early ROM with less than 3 weeks of immobilization)

ORIF using a posterior approach with two plates applied to either column

ORIF using a posterior approach with two plates applied to either column

Biomechanical studies support both parallel placement (one plate medial, one plate lateral) and perpendicular placement (one plate medial, one plate posterolateral) configurations

Biomechanical studies support both parallel placement (one plate medial, one plate lateral) and perpendicular placement (one plate medial, one plate posterolateral) configurations

Used with olecranon osteotomy or triceps split/peel (final muscle strength similar with both)

Used with olecranon osteotomy or triceps split/peel (final muscle strength similar with both)

In an open fracture, use ORIF by means of a triceps split through the defect, producing better results than osteotomy.

In an open fracture, use ORIF by means of a triceps split through the defect, producing better results than osteotomy.

Low-T fractures are more difficult and frequently require reoperation (almost 50%) for stiffness, but they can have good results.

Low-T fractures are more difficult and frequently require reoperation (almost 50%) for stiffness, but they can have good results.

“Bag-of-bones” technique—reasonable for demented patients and those who have severe medical comorbidities that prevent surgical treatment

“Bag-of-bones” technique—reasonable for demented patients and those who have severe medical comorbidities that prevent surgical treatment

Total elbow arthroplasty—useful for patients older than age 65 years, particularly with osteoporosis or rheumatoid arthritis

Total elbow arthroplasty—useful for patients older than age 65 years, particularly with osteoporosis or rheumatoid arthritis

Type I—Hahn-Steinthal; complete fracture of capitellum

Type I—Hahn-Steinthal; complete fracture of capitellum

Type II—Kocher-Lorenz; shear fracture of articular cartilage

Type II—Kocher-Lorenz; shear fracture of articular cartilage

Type I—If nondisplaced, splint for 2 to 3 weeks and then allow motion; if displaced more than 2 mm, use ORIF.

Type I—If nondisplaced, splint for 2 to 3 weeks and then allow motion; if displaced more than 2 mm, use ORIF.

Type II—If nondisplaced, splint for 2 to 3 weeks and then allow motion; if displaced, excise fragments.

Type II—If nondisplaced, splint for 2 to 3 weeks and then allow motion; if displaced, excise fragments.

3. Complications—nonunion (1%-11% with ORIF), olecranon osteotomy nonunion, ulnar nerve injury, heterotopic ossification (4% with ORIF), and AVN of capitellum

III ELBOW INJURIES (Table 11-10)

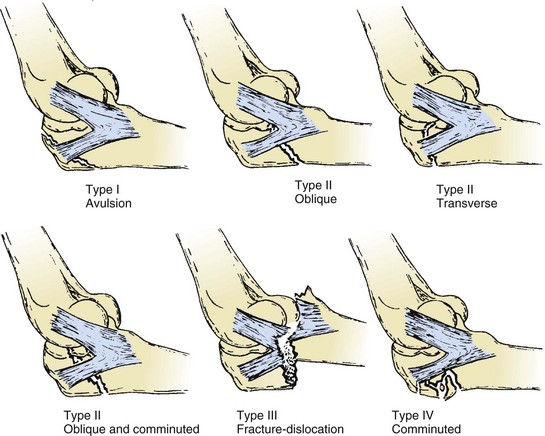

1. Classification—Colton (Figure 11-14)

Less than 1 to 2 mm displaced—Splint at 60 to 90 degrees for 7 to 10 days, followed by gentle active ROM exercises.

Less than 1 to 2 mm displaced—Splint at 60 to 90 degrees for 7 to 10 days, followed by gentle active ROM exercises.

Tension band—Use stainless steel wire or braided cable, not braided suture material.

Tension band—Use stainless steel wire or braided cable, not braided suture material.

The wire loop should be dorsal to the midaxis of the ulna, thus transforming tensile forces at the fracture site into compressive forces.

The wire loop should be dorsal to the midaxis of the ulna, thus transforming tensile forces at the fracture site into compressive forces.

Bury Kirschner wires in anterior cortex for increased stability. Protrusion through the anterior cortex, however, is associated with reduced forearm rotation.

Bury Kirschner wires in anterior cortex for increased stability. Protrusion through the anterior cortex, however, is associated with reduced forearm rotation.

Migration of Kirschner wires and prominent or painful hardware occurs in 71%.

Migration of Kirschner wires and prominent or painful hardware occurs in 71%.

IM screw fixation—It is inadequate by itself, but a properly placed 7.3-mm partially threaded screw with tension band wiring works well.

IM screw fixation—It is inadequate by itself, but a properly placed 7.3-mm partially threaded screw with tension band wiring works well.

Plate fixation (dorsal or tension side)—preferred technique for oblique fractures that extend distal to the coronoid process; more stable than tension band wiring

Plate fixation (dorsal or tension side)—preferred technique for oblique fractures that extend distal to the coronoid process; more stable than tension band wiring

Excision with triceps advancement—used for nonreconstructible proximal olecranon fractures in low-demand patients. Reattach close to the articular surface. Avoid resecting more than 50% of the olecranon.

Excision with triceps advancement—used for nonreconstructible proximal olecranon fractures in low-demand patients. Reattach close to the articular surface. Avoid resecting more than 50% of the olecranon.

3. Complications—decreased ROM, DJD, nonunion, ulnar nerve neurapraxia, and instability

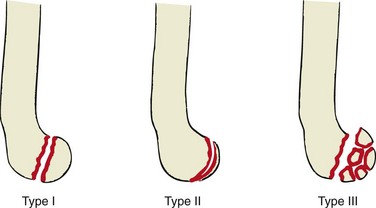

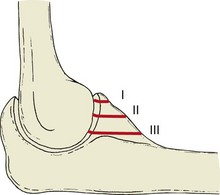

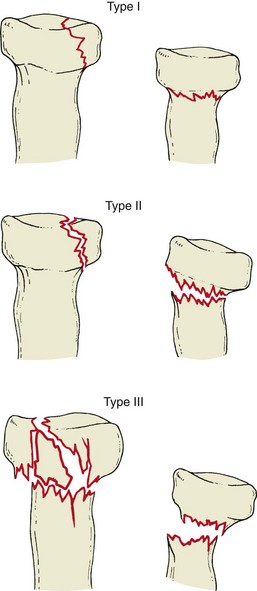

1. Classification (Figure 11-16)

Type II—partial articulation with displacement

Type II—partial articulation with displacement

Type III—comminuted fractures involving the entire head of the radius

Type III—comminuted fractures involving the entire head of the radius

Type IV—fractures associated with ligamentous injury or other associated fractures

Type IV—fractures associated with ligamentous injury or other associated fractures

Type I—Splint for no more than 7 days, and then allow motion.

Type I—Splint for no more than 7 days, and then allow motion.

Type II—Treatment is nonsurgical, with analgesics and active ROM as symptoms resolve, if the elbow is stable and there is no block to motion with good reduction. Otherwise, use ORIF. Surgery provides better results (90%-100% good or excellent).

Type II—Treatment is nonsurgical, with analgesics and active ROM as symptoms resolve, if the elbow is stable and there is no block to motion with good reduction. Otherwise, use ORIF. Surgery provides better results (90%-100% good or excellent).

Type III—Replace the radial head, usually with a metal implant. Use ORIF if fewer than three pieces. Excise only in elderly patients with low functional demands.

Type III—Replace the radial head, usually with a metal implant. Use ORIF if fewer than three pieces. Excise only in elderly patients with low functional demands.

Type IV—requires surgical repair: must use either ORIF or metallic radial head replacement. Do not excise without adding radial head implant.

Type IV—requires surgical repair: must use either ORIF or metallic radial head replacement. Do not excise without adding radial head implant.

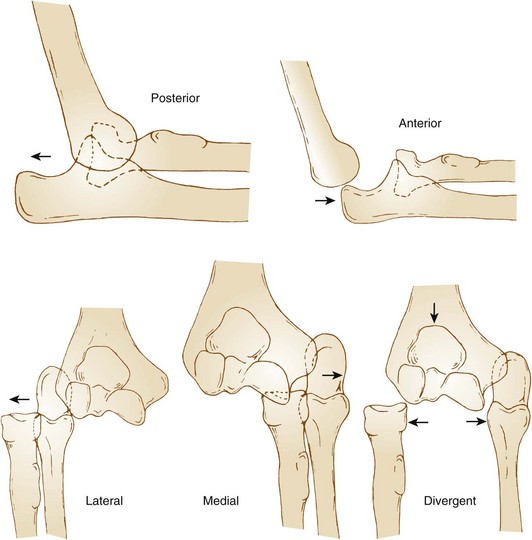

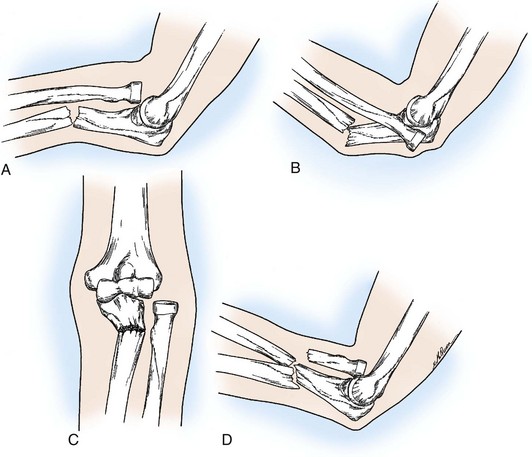

1. Classification (Figure 11-17)

Simple—brief immobilization (1 week) for most and then allow motion. Long-term results are good.

Simple—brief immobilization (1 week) for most and then allow motion. Long-term results are good.

Complex—Surgical treatment is indicated. Anterior or divergent dislocations are usually high-energy injuries with a much higher incidence of open wounds, neurovascular injury, fracture, and recurrent instability.

Complex—Surgical treatment is indicated. Anterior or divergent dislocations are usually high-energy injuries with a much higher incidence of open wounds, neurovascular injury, fracture, and recurrent instability.

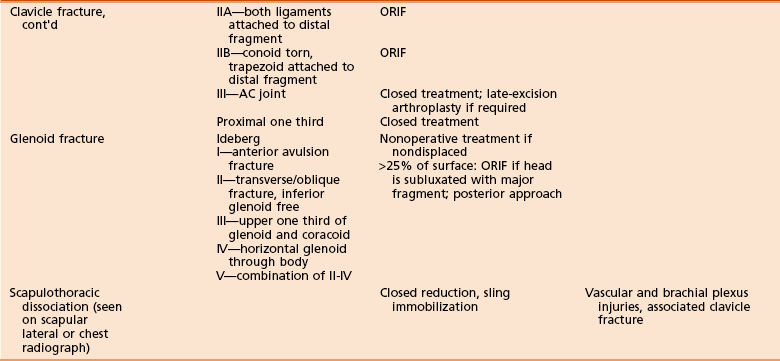

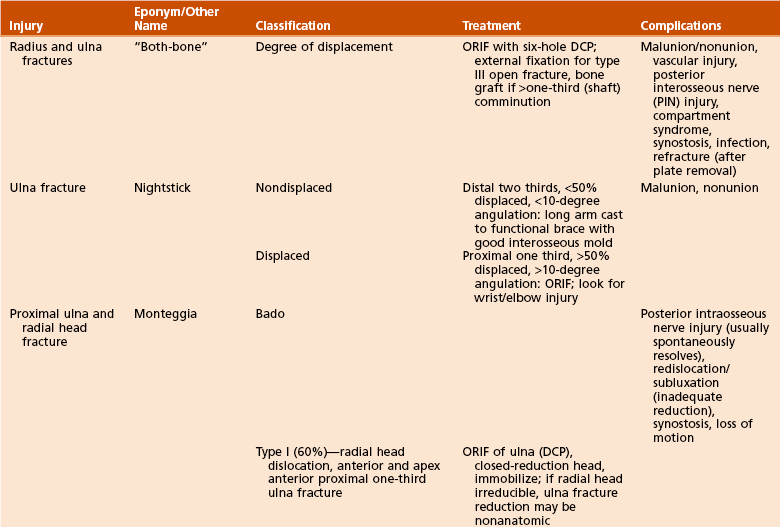

IV FOREARM FRACTURES (Table 11-11)

Table 11-11

Adult Radial and Ulnar Shaft Fractures and Dislocations

DCP, dynamic compression plate; ORIF, open reduction and internal fixation.

Bado classification (Figure 11-18)

Bado classification (Figure 11-18)

Type 1 (60%)—anterior radial head dislocation and apex anterior proximal third ulna fracture

Type 1 (60%)—anterior radial head dislocation and apex anterior proximal third ulna fracture

Type 2 (15%)—posterior radial head dislocation and apex posterior proximal third ulna fracture

Type 2 (15%)—posterior radial head dislocation and apex posterior proximal third ulna fracture

Type 3—lateral radial head dislocation and proximal ulnar metaphyseal fracture

Type 3—lateral radial head dislocation and proximal ulnar metaphyseal fracture

Type 4—anterior radial head dislocation and proximal third radius and ulna fractures

Type 4—anterior radial head dislocation and proximal third radius and ulna fractures

“Monteggia-equivalent or variant”—radial head fracture instead of dislocation

“Monteggia-equivalent or variant”—radial head fracture instead of dislocation

Interosseous membrane evaluation is important with Monteggia and Monteggia-equivalent injuries.

Interosseous membrane evaluation is important with Monteggia and Monteggia-equivalent injuries.

Physical examination—considered abnormal if greater than 3-mm instability is noted when the radius pulled proximally, indicating injury. If injury is greater than 6 mm, both the interosseous membrane and the triangular fibrocartilage complex are injured.

Physical examination—considered abnormal if greater than 3-mm instability is noted when the radius pulled proximally, indicating injury. If injury is greater than 6 mm, both the interosseous membrane and the triangular fibrocartilage complex are injured.

2. Treatment—All Monteggia fractures in adults should be treated with ORIF.

1. Classification—displaced versus nondisplaced

Malunion (stiffness/deformity)

Malunion (stiffness/deformity)

Refracture after plate removal

Refracture after plate removal

Associated with premature plate removal at less than 12 to 18 months

Associated with premature plate removal at less than 12 to 18 months

After plate removal, a functional forearm brace should be worn for 6 weeks and activity protected for 3 months.

After plate removal, a functional forearm brace should be worn for 6 weeks and activity protected for 3 months.

1. Classification—stable (traditional definition is <50% displacement) versus unstable (newer literature suggests that 25%-50% displacement or 10-15 degrees angulation is unstable)

D Distal third radius fracture with radioulnar dislocation (Galeazzi)

1. Diagnosis/classification—fracture of the radius (usually at the junction of the middle and distal thirds), with distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) instability

DRUJ is unstable in 55% of patients when the radial fracture is less than 7.5 cm from the articular surface.

DRUJ is unstable in 55% of patients when the radial fracture is less than 7.5 cm from the articular surface.

DRUJ is unstable in 6% of patients when the radial fracture is more than 7.5 cm away from the articular surface.

DRUJ is unstable in 6% of patients when the radial fracture is more than 7.5 cm away from the articular surface.

Signs of DRUJ instability include ulnar styloid fracture, widened DRUJ on posteroanterior view, dislocation on lateral view, and greater than or equal to 5 mm of radial shortening.

Signs of DRUJ instability include ulnar styloid fracture, widened DRUJ on posteroanterior view, dislocation on lateral view, and greater than or equal to 5 mm of radial shortening.

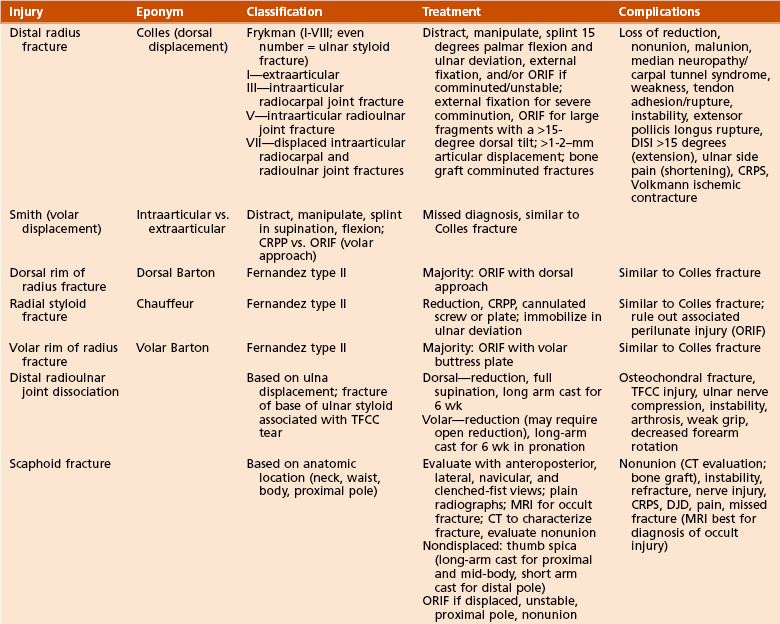

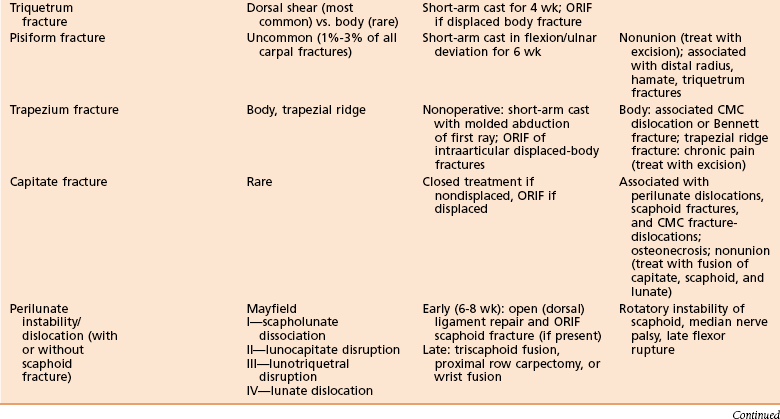

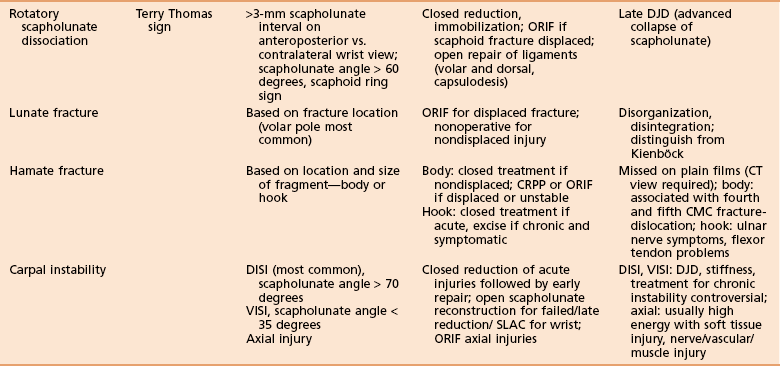

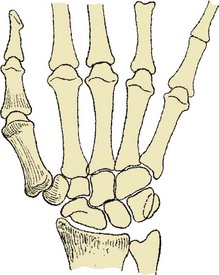

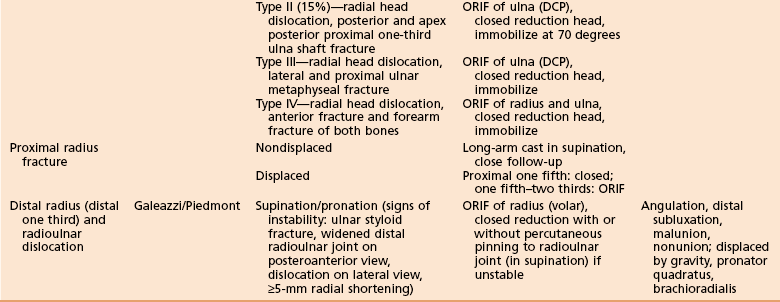

V WRIST FRACTURES (Table 11-12)

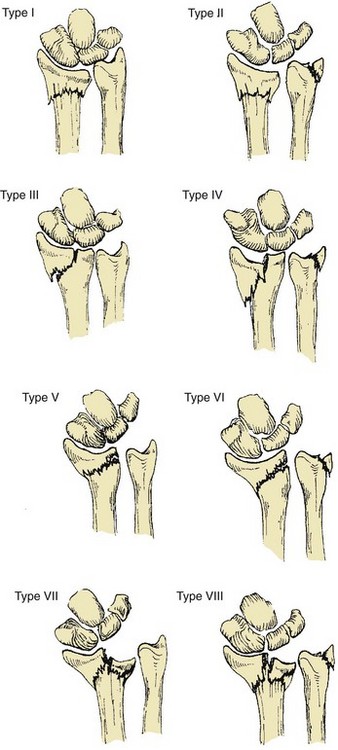

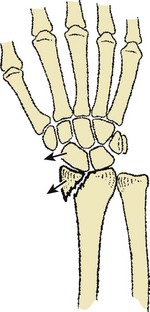

Frykman classification—types I to VIII (Figure 11-19)

Frykman classification—types I to VIII (Figure 11-19)

Types II, IV, VI, and VIII—include the ulnar styloid

Types II, IV, VI, and VIII—include the ulnar styloid

Type III—enters radiocarpal joint

Type III—enters radiocarpal joint

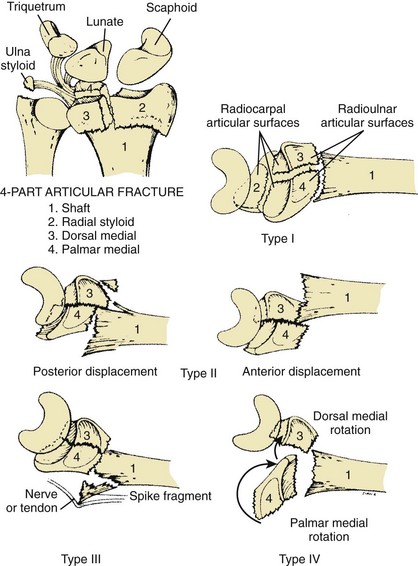

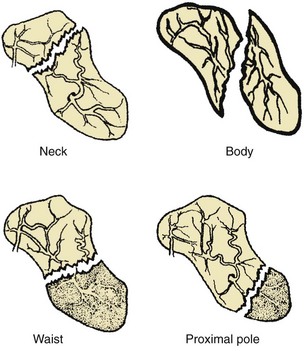

Melone classification (Figure 11-20—describes radiocarpal joint as four fragments:

Melone classification (Figure 11-20—describes radiocarpal joint as four fragments:

Types I to IV represent increasingly comminuted fractures of the aforementioned four anatomic regions and their parts.

Types I to IV represent increasingly comminuted fractures of the aforementioned four anatomic regions and their parts.

Type V is an extremely comminuted, unstable fracture without large, identifiable facet fragments).

Type V is an extremely comminuted, unstable fracture without large, identifiable facet fragments).

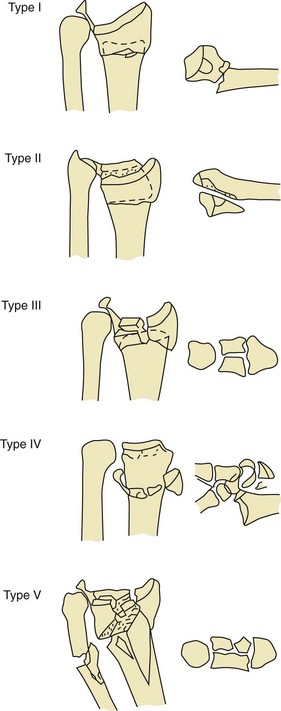

Fernandez classification (Figure 11-21)—based on the mechanism of injury and designed to guide treatment decision making

Fernandez classification (Figure 11-21)—based on the mechanism of injury and designed to guide treatment decision making

2. Treatment—based on the Fernandez classification

Type I—usually an extra-articular metaphyseal fracture. Comminution determines stability. The volarly displaced radial fracture is much more unstable. Use conservative treatment with reduction and casting if stable and CRPP versus internal/external fixation if unstable.

Type I—usually an extra-articular metaphyseal fracture. Comminution determines stability. The volarly displaced radial fracture is much more unstable. Use conservative treatment with reduction and casting if stable and CRPP versus internal/external fixation if unstable.

Type II—shearing injury of the joint surface (volar or dorsal lip or radial styloid). This type is usually unstable, and carpal subluxation frequently occurs. Treatment is with ORIF.

Type II—shearing injury of the joint surface (volar or dorsal lip or radial styloid). This type is usually unstable, and carpal subluxation frequently occurs. Treatment is with ORIF.

Type III—Articular compression (die-punch) injuries follow the patterns described by Melone.

Type III—Articular compression (die-punch) injuries follow the patterns described by Melone.

Conservative treatment if nondisplaced

Conservative treatment if nondisplaced

ORIF with disimpaction of the articular surface if displaced. Arthroscopy may be adjunct.

ORIF with disimpaction of the articular surface if displaced. Arthroscopy may be adjunct.

Type IV—rare and follows high-energy trauma

Type IV—rare and follows high-energy trauma

These are avulsion fractures with radiocarpal fracture dislocations.

These are avulsion fractures with radiocarpal fracture dislocations.

Surgical repair of the avulsed styloid usually restores stability. Treat with closed or, more frequently, open reduction, pin or screw fixation, or tension wiring.

Surgical repair of the avulsed styloid usually restores stability. Treat with closed or, more frequently, open reduction, pin or screw fixation, or tension wiring.

Type V—combination fractures of types I to IV after high-energy trauma. These are very severe and unstable fractures. There are always associated injuries. Treatment is open, with combined methods.

Type V—combination fractures of types I to IV after high-energy trauma. These are very severe and unstable fractures. There are always associated injuries. Treatment is open, with combined methods.

3. Outcomes—Restoration of anatomic alignment is the best predictor of a good outcome.

The loss of radial length and volar tilt is the most important, and radial inclination is less important.

The loss of radial length and volar tilt is the most important, and radial inclination is less important.

Articular step-offs of more than 1 to 2 mm also predict poor outcome.

Articular step-offs of more than 1 to 2 mm also predict poor outcome.

4. Complications—loss of reduction, malunion/nonunion, median nerve neuropathy, weakness, tendon adhesion, instability, extensor pollicis longus rupture, dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI), and Volkmann ischemic contracture

1. Dorsal rim radius fractures—dorsal Barton (Figure 11-22)

2. Radial styloid fractures—chauffeur fracture (Figure 11-23)

Diagnosis/classification—frequently high-energy trauma in young adults. Fernandez type II is associated with perilunate injuries.

Diagnosis/classification—frequently high-energy trauma in young adults. Fernandez type II is associated with perilunate injuries.

Treatment—CRPP or ORIF with screws; immobilize in ulnar deviation.

Treatment—CRPP or ORIF with screws; immobilize in ulnar deviation.

3. Volar rim radius fractures—volar Barton fracture (Figure 11-24)

Classification—Fernandez type II

Classification—Fernandez type II

Treatment—usually with ORIF by means of the volar approach; closed reduction (rarely)

Treatment—usually with ORIF by means of the volar approach; closed reduction (rarely)

Diagnosis/classification—fracture of the base of the ulnar styloid, associated with triangular fibrocartilage complex tear

Diagnosis/classification—fracture of the base of the ulnar styloid, associated with triangular fibrocartilage complex tear

Treatment—closed or open reduction to achieve anatomic ulnar styloid reduction; immobilize in supination

Treatment—closed or open reduction to achieve anatomic ulnar styloid reduction; immobilize in supination

Complications—osteochondral fracture, ulnar nerve compression, instability, arthrosis, weak grip, and decreased forearm rotation

Complications—osteochondral fracture, ulnar nerve compression, instability, arthrosis, weak grip, and decreased forearm rotation

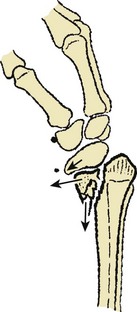

1. Classification—based on anatomic location (Figure 11-25)

Radiographs—anteroposterior, lateral, navicular, and clenched-fist views

Radiographs—anteroposterior, lateral, navicular, and clenched-fist views

MRI—to rule out occult fracture

MRI—to rule out occult fracture

CT with sagittal and coronal reconstructions—characterizes fracture and evaluates union

CT with sagittal and coronal reconstructions—characterizes fracture and evaluates union

Short-arm–thumb spica immobilization until definitive diagnosis and treatment plan are made.

Short-arm–thumb spica immobilization until definitive diagnosis and treatment plan are made.

Rule out occult fracture in those with a high index of suspicion and negative plain radiographs.

Rule out occult fracture in those with a high index of suspicion and negative plain radiographs.

1. Diagnosis/classification—The mechanism of injury is direct trauma. The classification is based on fracture location, with fracture of the volar pole being most common. Lunate fracture must be distinguished from Kienböck disease.

3. Complications—disorganization and disintegration of the lunate

Uncommon—1% to 3% of all carpal fractures

Uncommon—1% to 3% of all carpal fractures

Fifty percent with distal radius, hamate, or triquetrum fracture

Fifty percent with distal radius, hamate, or triquetrum fracture

2. Treatment—short arm cast with 30 degrees of wrist flexion and ulnar deviation for 6 weeks

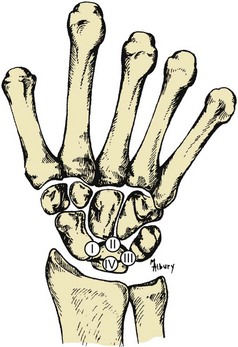

1. Mayfield classification (Figure 11-26)

Early (6 to 8 weeks)—open (dorsally); ligament repair and ORIF scaphoid fracture (if present)

Early (6 to 8 weeks)—open (dorsally); ligament repair and ORIF scaphoid fracture (if present)

Late—triscaphoid fusion, proximal row carpectomy, or wrist fusion

Late—triscaphoid fusion, proximal row carpectomy, or wrist fusion

3. Complications—rotatory instability of the scaphoid, median nerve palsy, and late flexor rupture

Nonoperative treatment—closed treatment if minor

Nonoperative treatment—closed treatment if minor

Operative treatment—for early treatment (<3 weeks), open reduction of scaphoid and lunate, with ligament repair and pinning

Operative treatment—for early treatment (<3 weeks), open reduction of scaphoid and lunate, with ligament repair and pinning

3. Complications—Widening of scapholunate is common. Another complication is late DJD.

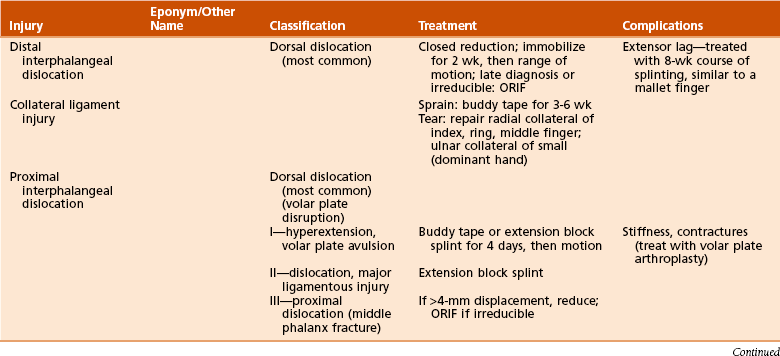

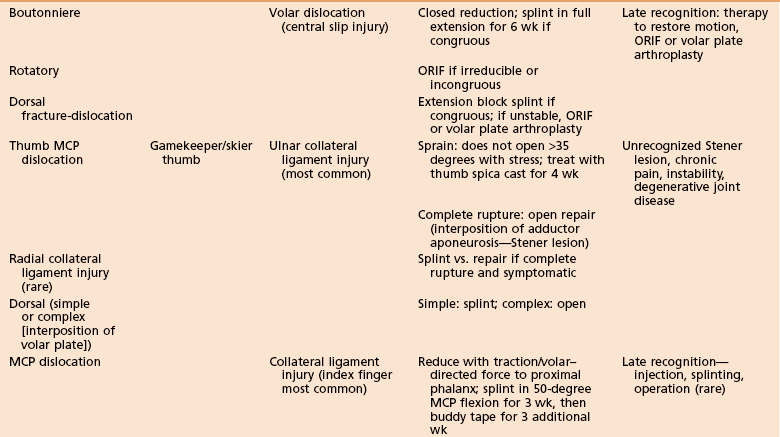

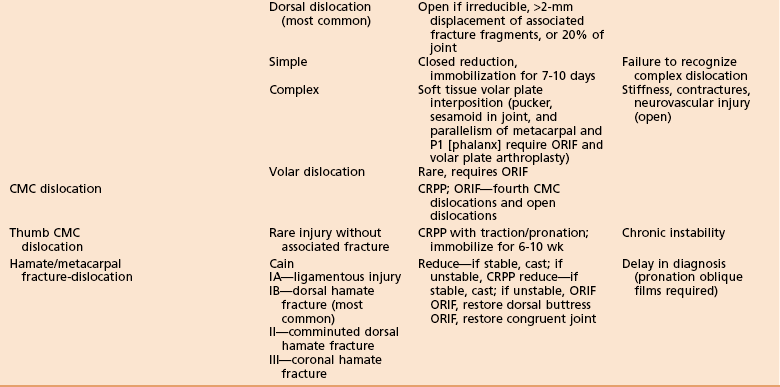

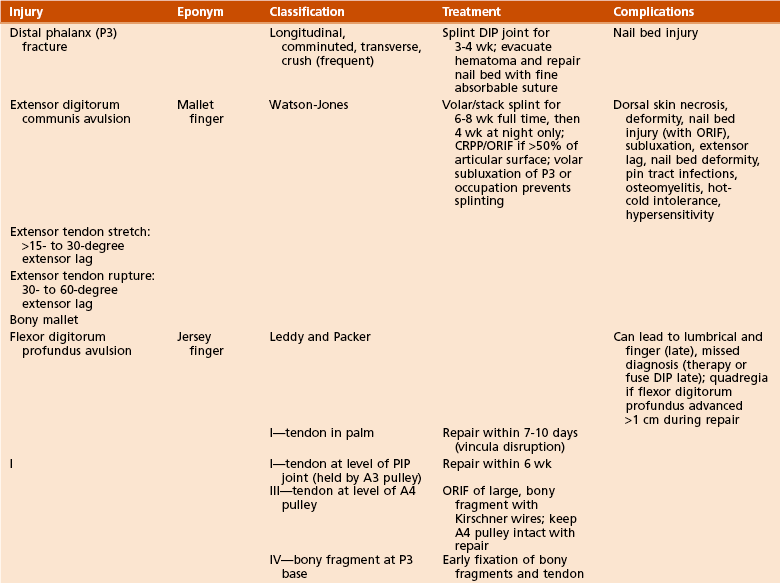

VII HAND INJURIES (Tables 11-13 and 11-14)

Table 11-13

Table 11-14

A Hamatometacarpal fracture-dislocation

B First carpometacarpal dislocation (Figure 11-28)

CRPP if the volar-ulnar fragment is too small for screw fixation and anatomic reduction is achieved

CRPP if the volar-ulnar fragment is too small for screw fixation and anatomic reduction is achieved

ORIF if there is a large fragment and/or the fracture is irreducible

ORIF if there is a large fragment and/or the fracture is irreducible

Rolando fracture—ORIF with 2-mm T-plate or blade plate if there are larger fragments, Kirschner wires for smaller fragments, and spanning external fixator for very severe comminution

Rolando fracture—ORIF with 2-mm T-plate or blade plate if there are larger fragments, Kirschner wires for smaller fragments, and spanning external fixator for very severe comminution

Extraarticular—spica cast for 4 weeks and CRPP if there is greater than 30 degrees angulation

Extraarticular—spica cast for 4 weeks and CRPP if there is greater than 30 degrees angulation

D First metacarpophalangeal joint injury/dislocation

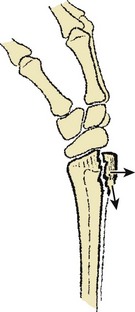

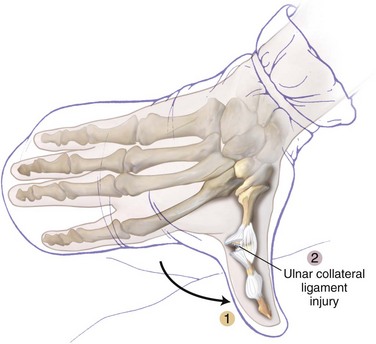

Ulnar collateral ligament injury (gamekeeper’s thumb)—the most common injury (Figure 11-29)

Ulnar collateral ligament injury (gamekeeper’s thumb)—the most common injury (Figure 11-29)

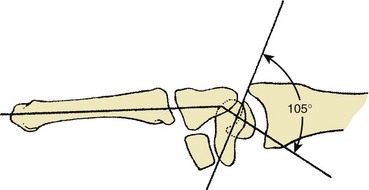

Figure 11-29 Gamekeeper’s thumb.

Sprain (joint opens <35-45 degrees) or complete tear

Sprain (joint opens <35-45 degrees) or complete tear

Stener lesion—interposition of adductor aponeurosis (prevents ulnar collateral ligament from healing back to bone)

Stener lesion—interposition of adductor aponeurosis (prevents ulnar collateral ligament from healing back to bone)

Radial collateral ligament injury—splint; late reconstruction only if necessary

Radial collateral ligament injury—splint; late reconstruction only if necessary

Dorsal—For a simple dislocation, splint for 3 weeks; for a complex dislocation, perform open repair.

Dorsal—For a simple dislocation, splint for 3 weeks; for a complex dislocation, perform open repair.

3. Complications—unrecognized injury or Stener lesion, leading to chronic instability and pain

E Finger metacarpophalangeal dislocation

1. Diagnosis/classification—index finger most often affected; characteristic skin puckering in the palm at the level of injury

2. Treatment—Reduce with volar force to the dorsal base of the proximal phalanx. May be irreducible; do not make multiple forceful attempts at reduction.

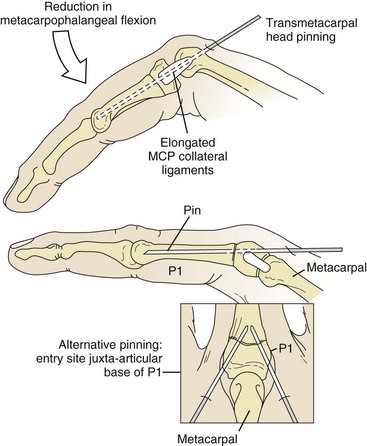

Collateral ligament injury—Splint in 50 degrees metacarpophalangeal flexion for 3 weeks and then buddy tape for 3 more weeks. Use ORIF if there is an avulsion fragment with greater than 2-mm displacement or greater than 20% articular involvement.

Collateral ligament injury—Splint in 50 degrees metacarpophalangeal flexion for 3 weeks and then buddy tape for 3 more weeks. Use ORIF if there is an avulsion fragment with greater than 2-mm displacement or greater than 20% articular involvement.

Dorsal—For a simple dislocation, splint for 7 to 10 days and then buddy tape. For a complex dislocation, perform open reduction (irreducible).

Dorsal—For a simple dislocation, splint for 7 to 10 days and then buddy tape. For a complex dislocation, perform open reduction (irreducible).

F Proximal interphalangeal dislocation

Dorsal—the most common dislocation

Dorsal—the most common dislocation

Avulsion of the volar plate occurs first, followed by a rent between the accessory and proper collateral ligaments.

Avulsion of the volar plate occurs first, followed by a rent between the accessory and proper collateral ligaments.

It can be further classified as stable or unstable as determined by maintenance of reduction.

It can be further classified as stable or unstable as determined by maintenance of reduction.

A fracture-dislocation of greater than 40% of the middle phalangeal joint surface will yield an unstable fracture-dislocation.

A fracture-dislocation of greater than 40% of the middle phalangeal joint surface will yield an unstable fracture-dislocation.

2. Treatment—Reduce with volar force to the dorsal base of the proximal phalanx. May be irreducible; do not make multiple forceful attempts at reduction.

Dorsal dislocation—Reduce with digital block anesthesia, longitudinal traction, and dorsal pressure applied to the proximal phalangeal head. Confirm concentric reduction and then apply dorsal block (about 30 degrees) splinting for 4 days, followed by vigorous joint motion to avoid stiffness.

Dorsal dislocation—Reduce with digital block anesthesia, longitudinal traction, and dorsal pressure applied to the proximal phalangeal head. Confirm concentric reduction and then apply dorsal block (about 30 degrees) splinting for 4 days, followed by vigorous joint motion to avoid stiffness.

Dorsal fracture-dislocation—similar reduction and stability test in extension. If stable, apply dorsal block splinting, excluding the last 45 degrees of extension; apply 30-degree block after 5-7 days; and buddy tape a week later. Unstable fracture-dislocation requires surgical fixation.

Dorsal fracture-dislocation—similar reduction and stability test in extension. If stable, apply dorsal block splinting, excluding the last 45 degrees of extension; apply 30-degree block after 5-7 days; and buddy tape a week later. Unstable fracture-dislocation requires surgical fixation.

Volar or lateral dislocation—closed reduction; ORIF if irreducible or incongruous. Try to reduce volar dislocation with metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints in flexion to avoid irreducible dislocation. Open treatment can be with pinning, external fixation, or open screw fixation.

Volar or lateral dislocation—closed reduction; ORIF if irreducible or incongruous. Try to reduce volar dislocation with metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints in flexion to avoid irreducible dislocation. Open treatment can be with pinning, external fixation, or open screw fixation.

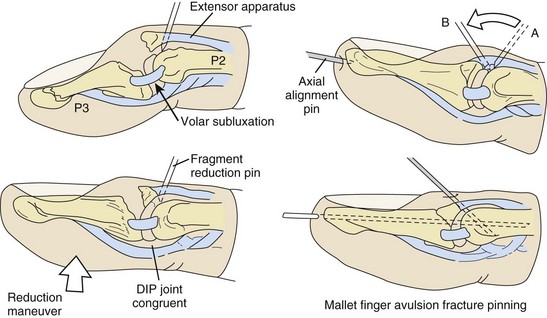

3. Complications—Loss of motion (can be severely disabling)