CHAPTER 4 The shoulder

Anatomical Features

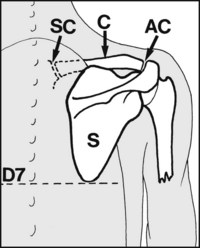

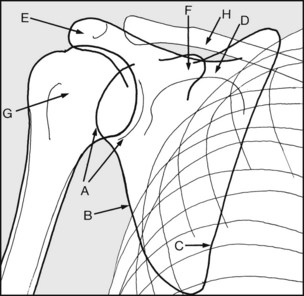

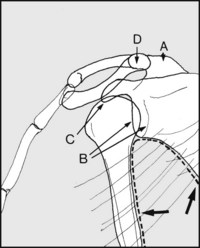

Fig. 4.A. The shoulder is complex, and it is important to note that it has two main components, namely the glenohumeral joint (between the head of the humerus and the glenoid) and the scapulothoracic joint (between the scapula and the chest wall). The latter is a physiological rather than an anatomical joint, as it has no synovial cavity.

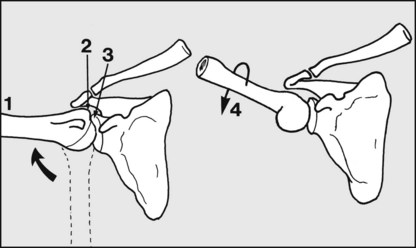

The glenohumeral joint accounts for about half of shoulder abduction (1), and this comes to an end when the greater tuberosity (2) impinges on the glenoid rim (3); the range of glenohumeral movement (about 90°) can be increased if the arm is externally rotated (4), thereby delaying the impingement of the greater tuberosity. Note that shoulder rotation occurs mainly in the glenohumeral joint.

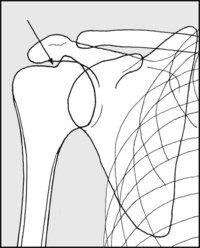

Fig. 4.B. In the scapulothoracic joint the scapula (S), moves over the rib cage and serratus anterior. It is supported by the clavicle (C) (which articulates with the scapula at the acromioclavicular joint (AC), and with the sternum at the sternoclavicular joint (SC)), and by trapezius, rhomboids, levator scapulae and serratus anterior. The inferior angle of the scapula normally lies at the level of D7.

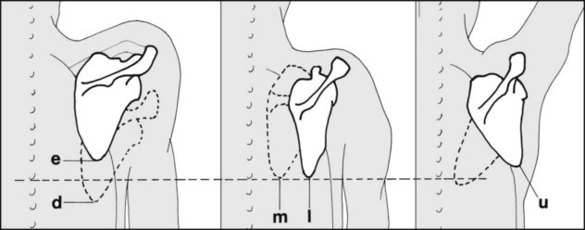

Fig. 4.C. The scapula, however, is normally a very mobile structure, varying in its position and permitting a wide range of scapulothoracic movements. The scapula may be elevated (e) or depressed (d), with a maximal total excursion in the order of 12 cm. (Note that elevation of the shoulder is a pure scapulothoracic movement, and must be distinguished from elevation of the arm. The latter term enjoys some popularity as a replacement for abduction or flexion, but because it is somewhat confusing it is probably best avoided.) The scapula may be rotated medially, or laterally and forwards (m, l) round the chest wall. It may also be tilted upwards (u) or downwards, with the glenoid angling in a corresponding fashion. When the glenoid is directed upwards, the angle between the vertebral border of the scapula and the vertical may reach 60°. Scapular movement is only possible if there is freedom at the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints, and between the scapula and the chest wall.

Fig. 4.D. Abduction of the shoulder (1):

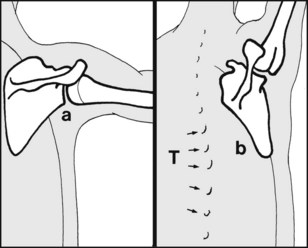

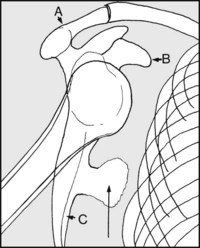

During the first 90° of abduction the glenohumeral joint is involved more than the scapula (a), whereas beyond 90° abduction is continued mainly by scapular movement (b). During the last 30° of abduction, when the glenohumeral joint is locked and the scapular attachments are tightening, movements of the spine may make a contribution: e.g. abduction of the shoulder may lead to some lateral flexion of the thoracic spine (T). The cervical spine may also laterally flex to the other side, to preserve the posture of the head. When both arms are abducted, neither the thoracic nor the cervical spine laterally flexes, but there may be an increase in lumbar lordosis.

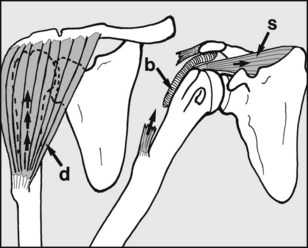

The deltoid muscle (d) arises from the lateral end of the clavicle, the acromion and the spine of the scapula; it is attached to the deltoid tubercle of the humerus. When the arm is at the side, the deltoid acting alone is incapable of initiating abduction: its contraction tends to raise the head of the humerus relative to the glenoid. On the other hand, when the arm is at the side the supraspinatus (s) is in its position of greatest mechanical advantage; with deltoid it forms a couple and initiates abduction (which is then taken over by deltoid). A tear of the supraspinatus (or relevant part of the shoulder cuff) will prevent the normal initiation of abduction, which will then only be possible by trick movements. (b = subdeltoid bursa)

In spite of the tendency for glenohumeral and scapular movements to dominate specific portions of the abduction arc, it should be noted that there is no abrupt transition from one to the other, and indeed all the shoulder girdle joints make a contribution to nearly every movement that takes place in this region. The exceptions are shrugging movements, which do not involve the glenohumeral joint, and external rotation, which does not involve scapular movement.

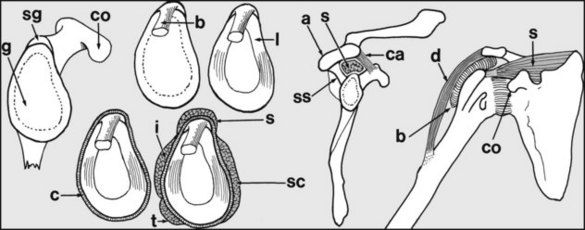

The shoulder cuff: The glenoid (g) is widest inferiorly. Anteriorly lies the coracoid (co), and above is the supraglenoid tubercle (sg), from which the long head of biceps (b) arises. The fibrocartilaginous labrum (l) deepens the glenoid concavity and is attached to its peripheral margin, along with the joint capsule (c). The capsule is reinforced with the musculotendinous insertions of supraspinatus (s), subscapularis (sc), infraspinatus (i) and teres minor (t), which fuse with the capsule laterally, forming a complete tissue annulus (the shoulder cuff). The supraspinatus is its most important part. This in effect runs through a tunnel formed by the spine of the scapula (ss), the acromion (a), and the coracoacromial ligament (ca). It is partly separated from the acromion by the subdeltoid bursa (b).

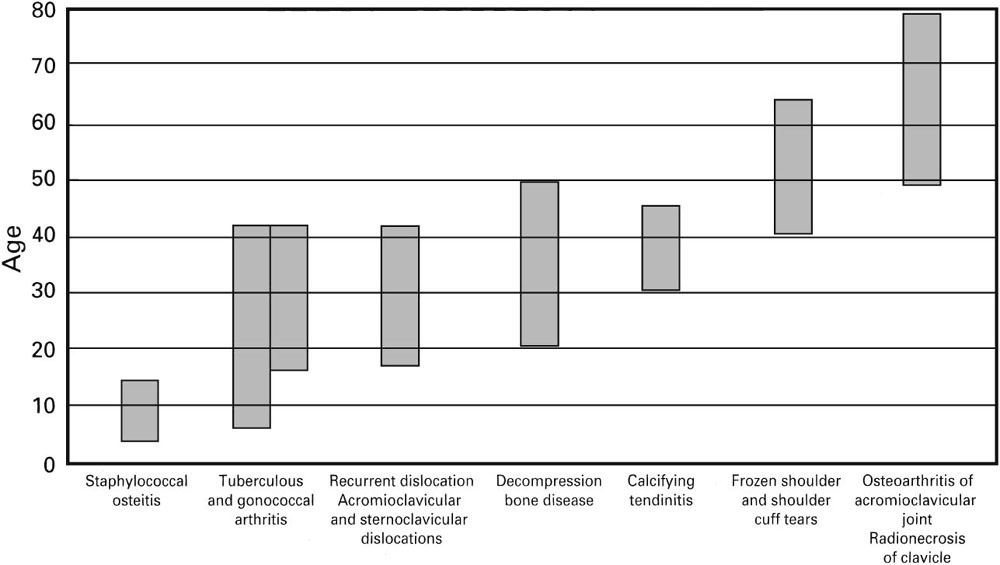

Common Pathology around the Shoulder

The commonest cause of shoulder pain is cervical spondylosis. Pain from irritation of nerve roots in the neck is referred to the shoulder in the same way as pain originating in the lumbar spine may be referred to the hip. There may on occasion be simultaneous pathology in both shoulder and neck, but differentiation is usually straightforward; in particular, restriction of movements of the shoulder with pain at the extremes points to the shoulder as the site of the principal pathology.

Impingement Syndrome

The rotator cuff (and the subdeltoid bursa) may be compressed during glenohumeral movement, giving rise to pain and disturbance of scapulothoracic rhythm. The commonest site is subacromial, causing a painful arc of movement between 70° and 120° abduction. Compression may also occur beneath the acromioclavicular joint itself, when there may be a painful arc of movement during the last 30° of abduction, or deep to the coracoacromial ligament. Symptoms may occur acutely (e.g. in young sportsmen, especially those engaging in activities involving throwing) or be chronic, particularly in the older patient. In this latter group there are usually degenerative changes in the acromioclavicular joint which lead to a reduction in size of the supraspinatus tunnel; this may cause attrition and rupture of the shoulder cuff.

There is a small group of cases where there is no narrowing of the tunnel, but where there is often thickening of the subdeltoid bursa or of the rotator cuff tendons. Note also that severe shoulder pain may occur in patients being dialysed, and is often due to subacromial impingement on amyloid deposits.

In the acute case, symptoms generally respond to rest or modification of activities. In the chronic case, physiotherapy, analgesics, and the targeted injection of local anaesthetic and steroids may be helpful. If symptoms become persistent and remain disabling, surgery may be required. The commonest procedure (by open surgery or by arthroscopy) is a decompression of the subacromial space; this may involve excision of osteophytes, an AC joint arthroplasty, and excision of the coracoacromial ligament.

Rotator Cuff Tears

In the young athletic patient the shoulder cuff may be torn as the result of a violent traumatic incident. In the older patient tears may occur spontaneously (e.g. in a cuff weakened as a result of chronic impingement and attrition) or follow more minor trauma, such as sudden arm traction. It may occur in patients suffering from instability of the shoulder joint.

Most commonly the supraspinatus region is involved, and the patient has difficulty in initiating abduction of the arm. In other cases the torn shoulder cuff impinges on the acromion during abduction, giving rise to a painful arc of movement. Although the range of passive movements is not initially disturbed, limitation of rotation may supervene, so that many of these cases, particularly in older patients, become ultimately indistinguishable from those suffering from so-called frozen shoulder. In the young patient, surgical repair of acute tears is generally advised. In the older patient the indications for surgery are less clear, but operative repair, often combined with a decompression procedure, is becoming increasingly recommended. Arthroscopic repair may be performed, although it is technically demanding. In every case, prolonged postoperative physiotherapy is usually required.

Rotator Cuff Arthropathy

If complete rotator cuff tears are neglected, the loss of soft tissue above the head of the humerus may lead to its proximal migration. Friction between the humeral head and the acromion may result in bony collapse and gross degenerative changes in the glenohumeral joint, which in severe cases may lead to joint replacement having to be considered.

‘Frozen Shoulder’/Idiopathic Adhesive Capsulitis of the Shoulder

‘Frozen shoulder’ is a clinical syndrome characterised by gross restriction of shoulder movements and which is associated with contraction and thickening of the joint capsule. It is a condition that affects the middle-aged, in whose shoulder cuffs degenerative changes are occurring. Restriction of movements is often severe, with virtually no glenohumeral movements possible, but in the milder cases rotation, especially internal rotation, is primarily affected. Pain is often severe and may disturb sleep. There is frequently (but not always) a history of a minor trauma, which is usually presumed to produce some tearing of the degenerating shoulder cuff, thereby initiating the low-grade prolonged inflammatory changes and contraction of the shoulder cuff responsible for the symptoms. In a number of cases there are fibrotic changes in the coracohumeral ligament which resemble those found in Dupuytren’s disease. In some cases the condition is initiated by a period of immobilisation of the arm, not uncommonly as the result of the inadvised prolonged use of a sling after a Colles’ fracture. It is commoner on the left side, and in an appreciable number of cases there is a preceding episode of a silent or overt cardiac infarct. It is commoner in diabetics. Radiographs of the shoulder are almost always normal. If untreated, pain subsides after many months, but there may be permanent restriction of movements. Generally those with the most severe initial symptoms have the poorest outcome in terms of final mobility and overall function.

The main aim of treatment is to improve the final range of movements in the shoulder, and graduated shoulder exercises are the mainstay of treatment. In some cases where pain is a particular problem, hydrocortisone injections into the shoulder cuff may be helpful. In a few cases, if there is no improvement with appropriate treatment for 4 months, manipulation of the shoulder under general anaesthesia or athroscopic capsular release may be helpful in restoring movements in a stiff joint.

Calcifying Supraspinatus Tendinitis

Degenerative changes in the shoulder cuff may be accompanied by the local deposition of calcium salts. This process may continue without symptoms, although radiographic changes are obvious. Sometimes, however, the calcified material may give rise to inflammatory changes in the subdeltoid bursa. Sudden, severe incapacitating pain results; the shoulder becomes acutely tender, and is often swollen and warm to the touch. It is important to differentiate the condition from an acute infection, or an acute attack of gout. Symptoms are relieved by the removal of the material by aspiration, curettage, or shock-wave therapy, but often local injections of hydrocortisone suffice. Note that the joint is frequently so acutely tender that general anaesthesia is necessary for any attempted aspiration and injection of hydrocortisone. Ultrasound-guided needling in combination with high-energy shock-wave therapy is more effective than shock-wave therapy alone, giving better elimination of the deposits, better clinical results and lesser need for surgery.

Osteoarthritis of the Acromioclavicular Joint

Arthritic changes in the acromioclavicular joint may give rise to prolonged pain associated with shoulder movements (with or without shoulder cuff involvement and the production of an impingement syndrome). There is usually an obvious prominence of the joint from arthritic lipping, with well localised tenderness. Conservative treatment with local heat and exercises may be helpful, but occasionally, in severe persistent cases, acromionectomy may be considered.

Osteoarthritis of the Glenohumeral Joint

Osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint is rare, and when it occurs is most frequently secondary to avascular necrosis of the humeral head. This may be idiopathic in origin, or follow a fracture of the proximal humerus which interferes with the blood supply of its head. It may result from faulty decompression regimens in deep-sea divers, caisson workers and pilots, and it may follow radiotherapy (radionecrosis), particularly following treatment for carcinoma of the breast. If empirical treatment fails, joint replacement may have to be considered.

Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Shoulder

Rheumatoid arthritis is more common than osteoarthritis in the shoulder, and the features are similar to those of the condition in other joints. It is necessary to localise the site of the main pathology so that treatment may be directed effectively, and diagnostic sequential injections (into the acromioclavicular joint, the shoulder cuff, and then the glenohumeral joint) may be helpful in this respect. Medical treatment and intra-articular injection therapy are tried first. In more advanced cases, where the symptoms are the result of impingement, decompression procedures may be highly effective. Where the glenohumeral joint is severely diseased, joint replacement will generally produce pain relief and improved function.

Instabilities of the Shoulder Joint

Recurrent Dislocation of the Shoulder

The shoulder may be affected by anterior, posterior or inferior instability. When the shoulder is unstable in several planes, then multidirectional instability (‘loose shoulder’) is said to be present.

Anterior instability is the commonest, and in many cases this follows a frank dislocation of the shoulder. It occurs most frequently in the 20–40-year age group. There may be a history of repeated dislocations in which the causal trauma has become progressively less severe (recurrent anterior dislocation of the shoulder). The shoulder is often symptom free between incidents, but there may be some pain and weakness. Surgical repair is generally advised if there have been four or more dislocations, but each case must be carefully assessed to exclude shoulder laxity in other planes: many case of failed reconstruction are due to an associated posterior instability.

Trauma to the shoulder may also result in posterior dislocation, which can proceed to recurrent posterior dislocation. Posterior dislocation of the shoulder is much less common than anterior dislocation and the diagnosis is sometimes overlooked, especially when only one radiographic projection is taken. Surgical reconstruction is sometimes required, but this may fail if concurrent anterior instability is not taken into account.

Anterior and multidirectional instabilities may occur without previous trauma, and never proceed to frank dislocations or obvious subluxations. The condition may be congenital in origin. The primary complaints are of pain and weakness in the shoulder, and the rapid onset of joint fatigue during activity. The arm may feel ‘dead’. In the case of multidirectional instabilities muscle retraining is generally advocated, although surgical reconstruction is sometimes attempted.

Recurrent dislocation of the shoulder should be differentiated from habitual dislocation. In the latter the patient is often psychotic or suffering from a joint laxity syndrome. The shoulder repeatedly dislocates without much in the way of pain; the patient is often able to dislocate and reduce the shoulder voluntarily and with ease; and the radiological changes that are found in recurrent dislocation are not present in habitual dislocation. When habitual dislocation is found in children the prognosis is good, and surgery is never indicated. In the adult, surgery is usually best avoided (as the results are often poor), but good results are being claimed for biofeedback re-education of the shoulder muscles.

Infections around the Shoulder

Staphylococcal osteitis of the proximal humerus is the commonest infection occurring near the shoulder in this country at present; nevertheless, it is comparatively uncommon.

Tuberculosis of the shoulder is now rare. In the moist form, commonest in the first two decades of life, the shoulder is swollen, there is abundant pus production, and sinuses may form; the progress is comparatively rapid and destructive. In the dry form, caries sicca, an older age group is affected and the progress is slow, with little destruction or pus formation. (However, it should be noted that it is now thought that many of the cases of caries sicca described in the past were in fact suffering from frozen shoulder.)

Gonococcal arthritis of the shoulder is uncommon, but when it occurs there is moderate swelling of the joint and great pain, which often seems out of keeping with the physical signs.

Miscellaneous Conditions around the Shoulder

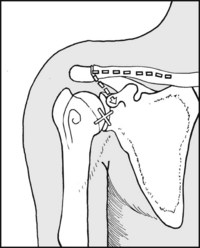

Acromioclavicular dislocation

The acromioclavicular joint may be disturbed as a result of a fall on the outstretched hand or on the point of the shoulder. If care is taken during examination, a lesion of this joint will not be confused with one of the glenohumeral joint. In major injuries the conoid and trapezoid ligaments are torn and the clavicle is very unstable: surgical fixation of the clavicle to the coronoid (by a screw or a sling procedure) is sometimes advised. In less severe cases the acromioclavicular capsular ligaments only are torn. Although the outer end of the clavicle becomes prominent, it follows the movement of the acromion and conservative treatment with a sling for several weeks is all that is required. These injuries are frequently missed, as they often do not show in the routine recumbent radiographs of the shoulder.

Clavicle

Primary pathology in the clavicle is uncommon, but a cause of confusion is pathological fracture due to radionecrosis years after treatment for breast carcinoma. The fracture may be preceded by pain for many months, and be mistaken for metastatic spread.

Scapula

Snapping scapula

A patient may complain of a grinding sensation arising from beneath the scapula. This is often due to a rib prominence, but in some cases it may be caused by an exostosis arising from the deep surface of the scapula itself. When symptoms are persistent, excision of such an exostosis may give relief.

High scapula

There are several related congenital malformations affecting the neck and shoulder girdle. In the most minor cases one scapula may be a little smaller than the other and be more highly placed; in more severe cases one or both shoulders are highly situated, the scapulae are small, and there may be webs of skin running from the shoulder to the neck (Sprengel shoulder). In the Klippel–Feil syndrome the neck is short and there are multiple anomalies of the cervical vertebrae, which may include vertebral body fusions and spina bifida. Apart from highly placed scapulae, other congenital lesions may be found in association with the Klippel–Feil syndrome; these include diastomatomyelia resulting in tethering of the spinal cord and neurological involvement; lumbosacral lipomata; and renal abnormalities.

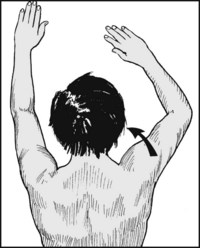

Winged scapula

The patient complains of prominence of the scapula, its vertebral border being raised from normal contact with the chest wall. This is due to weakness of the serratus anterior. The cause may be primarily muscular (as in progressive muscular dystrophy) or follow traumatic paralysis of the long thoracic nerve. Active treatment is seldom necessary.

Ruptured biceps tendon

Rupture of the long head of biceps may occur spontaneously or as a result of a sudden muscular effort, usually in an elderly or middle-aged person in whom degenerative tendon changes are present. No treatment is usually required. In some cases the tendon may cause a detachment of its origin from the superior part of the glenoid (SLAP lesion); in the young athletic patient surgical reattachment may be advocated.

Biceps tendon instability and tendininitis

Anchorage of the biceps tendon in its groove may become faulty, so that certain movements of the shoulder may cause it to snap in and out of its normal location. This often occurs in association with a shoulder cuff tear, and isolated tendon lesions may be difficult to differentiate from pure cuff tears. The tendon may become inflamed (biceps tendinitis). No specific treatment is usually required.

Sternoclavicular joint

Dislocation of the sternoclavicular joint is comparatively uncommon; there is always a history of trauma, and the joint asymmetry is obvious if looked for. In some cases, especially where the medial end of the clavicle comes to lie behind the sternum, there may be an associated thoracic outlet syndrome.

Good radiographs are often hard to obtain and their interpretation is difficult. The diagnosis should be made primarily on clinical grounds. Symptoms of pain on movement normally settle spontaneously, and only rarely is surgical repair required.

Assessment of Combined Shoulder and Elbow Function

It should be noted that overall function in the arm is disproportionately affected when the elbow is also involved. The American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons have devised a scoring system which may be used to gauge overall function in both joints. Each activity is evaluated on a scale of 0–4 and the results may be summed (0 = unable; 1 = only with assistance; 2 = with difficulty; 3 = mild compromise; 4 = normal).

Assessment of Total Upper Limb Function: Dash/Quick Dash

Rather than restricting the assessment of upper limb function to the shoulder and elbow alone it is often preferable to consider function in the arm as a whole. The so-called DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, Elbow and Hand) questionnaire was developed to address this issue. It was shown to be reliable, but the 30 items involved along with their subsequent grading made it somewhat time-consuming. A simplified 11-item version (QuickDASH) has been shown to be equally reliable. The function revealed by each question given below is graded in a range 1–5, and their sum forms the basis of a guide to overall function.

The QuickDASH system has optional additional modules dealing with the effects of limb disability on work, sport and the performing arts. These are included here for completeness.

Work Module

Sports/Performing Arts Module

Scoring for each of the three modules described is done by adding up the values for all the items in that module, dividing the sum by the number of items, subtracting 1, and then multiplying by 25: i.e. Score = [(sum of items/number of items) − 1] × 25.

For example, if all 11 items in the disability module added up to 44, the Disability/Symptoms score would be 75.

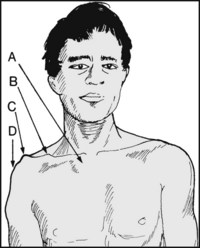

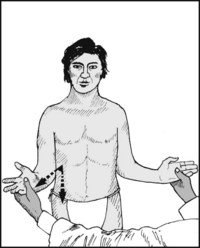

The front: Note whether any of the following are present: (A) Prominent sternoclavicular joint (subluxation). (B) Deformity of clavicle (old fracture). (C) Prominent acromioclavicular joint (subluxation or osteoarthritis). (D) Deltoid wasting (disuse or axillary nerve palsy).

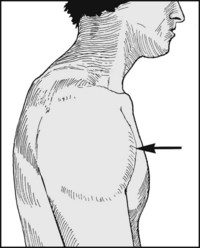

The side: Note if there is any swelling of the joint, suggesting infection or inflammatory reaction from, for example, calcifying supraspinatus tendinitis, pyogenic infection of the glenohumeral joint, or trauma.

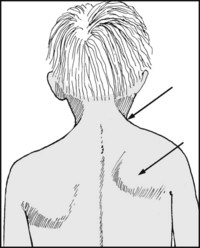

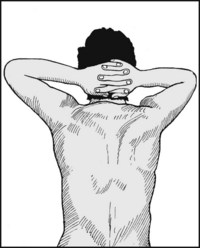

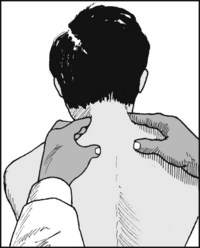

From behind: Are the scapulae normally shaped and situated, or small and high, as in Sprengel’s shoulder and the Klippel–Feil syndrome? Is there webbing of the skin at the root of the neck, also typical of the latter? Is there winging of the scapula owing to paralysis of serratus anterior?

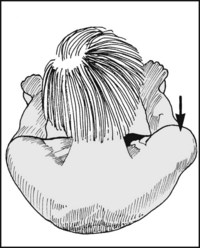

From above: Again look for swelling of the shoulder, deformity of the clavicle, asymmetry of the supraclavicular fossae.

Palpate the anterior and lateral aspects of the glenohumeral joint. Diffuse tenderness is suggestive of infection or calcifying supraspinatus tendinitis. Very marked tenderness is particularly associated with calcifying suprapinatus tendinitis and gonococcal infections.

Continue the examination by palpating the upper humeral shaft and head via the axilla. Exostoses of the proximal humeral shaft are often readily palpable by this route.

Tenderness over the acromioclavicular joint is found after recent dislocations, and in osteoarthritis of the joint. In the latter lipping is usually palpable, and crepitus may be detectable when the arm is abducted.

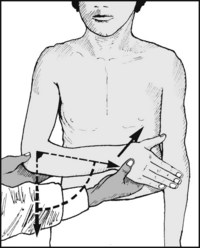

4.8. Palpation (4): Paxinos sign:

This test may be used to confirm the presence of osteoarthritis in the acromioclavicular joint. Standing behind the patient, and using your left hand to examine the right shoulder, hook the thumb under the posterolateral margin of the acromion and press in an anterosuperior direction; at the same time push the clavicle inferiorly with the index and middle fingers. The test is positive if the patient experiences pain.

Press below the acromion and abduct the arm. Sudden tenderness occurring during a portion of the arc of movement is found in tears and inflammatory lesions involving the shoulder cuff and/or the subdeltoid bursa.

Palpate the length of the clavicle. Tenderness is found in sternoclavicular dislocations and infections (particularly tuberculosis), tumours (rare), and radionecrosis (usually after treatment for breast cancer). Radiological examination of the clavicle is essential if local tenderness is found.

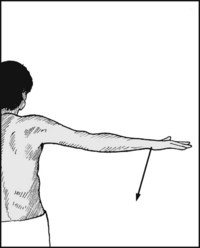

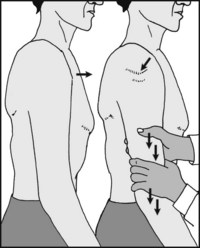

4.11. Movements: abduction (1):

Ask the patient to abduct both arms; observe the smoothness of the movement and the range achieved. A full, free and painless range is rare in the presence of any significant pathology in the shoulder region.

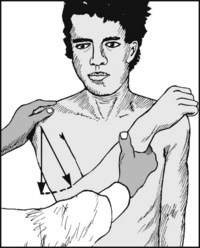

4.12. Movements: abduction (2):

Note whether the patient has any problem with initiating abduction. Difficulty in doing so is suggestive of a major shoulder cuff tear. A history of violent injury may be obtained in the young adult. In the middle-aged or elderly patient a tear may follow comparatively minor trauma, or occur spontaneously in a shoulder cuff weakened by attrition from chronic impingement.

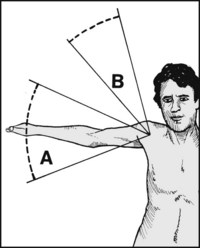

4.13. Movements: abduction (3):

Note pain during abduction (which may have to be assisted): (A) During the arc 70–120°, suggestive of shoulder cuff impingement in the region of the acromion. (B) During the latter phase of abduction, suggestive of shoulder cuff impingement in the region of the acromioclavicular joint or coracoacromial ligament, or from osteoarthritis of the acromioclavicular joint. (See Frame 4.34 for other rotator cuff screening tests.)

4.14. Movements: abduction (4):

If the patient cannot abduct the arm actively, attempt to do this passively, remembering to rotate the arm externally while doing so. A full range indicates an intact glenohumeral joint.

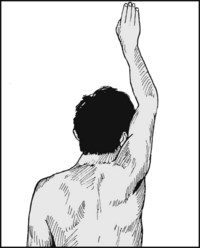

4.15. Movements: abduction (5):

Ask the patient to hold the arm in the vertical position himself. If he can do so, deltoid and the axillary nerve are likely to be intact.

4.16. Movements: abduction (6):

If the patient has passed the last test, ask him to lower the arm to the side. Again note the presence of any painful arc of movement. Sudden dropping of the arm in the process is a common finding in major shoulder cuff tears (drop arm test).

4.17. Movements: abduction (7):

Measure the range of abduction. In the normal shoulder the arm can touch the ear with only slight tilting of the head. The shoulders have already been compared (see Frame 4.11).

4.18. Movements: abduction (8):

If both active and passive movements are restricted, fix the angle of the scapula with one hand and try to abduct the arm with the other. Absence of movement indicates a fixed glenohumeral joint, the previously noted movements having been entirely scapular.

4.19. Movements: adduction in extension:

Place one hand on the shoulder and swing the arm, flexed at the elbow, across the chest.

4.20. Movements: forward flexion:

Ask the patient to swing the arm forwards and lift it above his head. View the patient from the side.

Normal range: 0–165°. (Note that instead of measuring abduction and flexion, some prefer to measure the maximum height to which the arm can be raised, irrespective of the planes of movement – and record this as ‘total active elevation’; but see note in Frame 4.C).

4.21. Movements: backwards extension:

Ask the patient to swing the arm directly backwards, again viewing and measuring from the side.

4.22. Movements: horizontal flexion and adduction:

Occasionally measurement of this angle may be helpful, but it need not be routine. View the patient from above. The arm is moved forwards from a position of 90° abduction.

Normal range: 0–140°. Note that pain during this manoeuvre is common in osteoarthritis or trauma to the acromioclavicular joint.

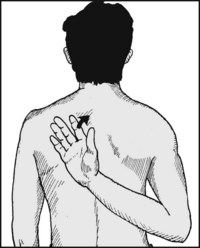

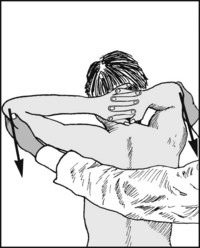

4.23. Movements: rotation screening tests (1):

Ask the patient to place the hand behind the opposite shoulder blade. This is a useful test of internal rotation in extension.

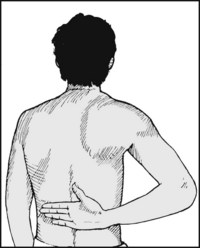

4.24. Movements: rotation screening (2):

With slight restriction he will not be able to get the hand far up the back, and with severe restriction he will not be able to get it behind the back at all. This movement is commonly affected in frozen shoulder. To test subscapularis (which may be torn by violent external rotation, hyperextension, or anterior dislocation of the shoulder), ask the patient if he can draw the hand away from contact with the back when in the position shown.

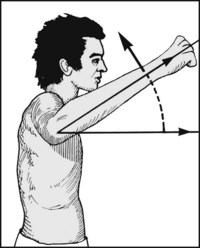

4.25. Movements: rotation screening (3):

Ask the patient to place both hands behind the head to screen external rotation at 90° abduction. Compare the two sides. Lack of success or restriction is common in frozen shoulder.

4.26. Movements: rotation screening (4):

Sometimes in the last test the patient manages to get the hand on the affected side behind the head, but in a position of horizontal flexion. If so, gently pull both elbows backwards, noting any difference. (Pain and restriction are common in frozen shoulder.)

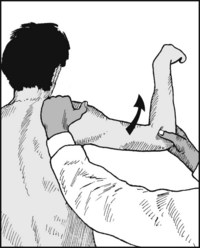

4.27. Movements: internal rotation in abduction:

Abduct the shoulder to 90°, and flex the elbow to a right angle. Ask the patient to lower the forearm from the horizontal plane.

4.28. Movements: external rotation in abduction:

From the same starting position with the forearm parallel to the ground, ask the patient to raise the hand, keeping the shoulder in 90° abduction.

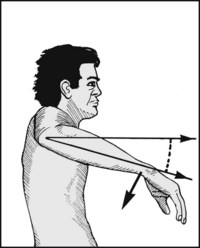

4.29. Movements: external rotation in extension:

Place the elbows into the sides and flex them to 90° with the hands facing forwards. Move the hands laterally, comparing one side with the other.

Normal range: 70°. Note that an increase in external rotation in extension is a feature of tears of the subscapularis muscle (see also Frame 4.24).

4.30. Movements: internal rotation in extension:

Move the hand to the chest from the facing forward position.

For most clinical work, assessment of abduction and screening rotation in the shoulder should suffice (but record angular ranges of movements in all planes for monitoring progress and for medico-legal reports).

4.31. Shoulder elevation and depression:

This may be assessed by direct measurement (see Frame 4.C), but Hallaçeli and Günal advocate the use of a goniometer, centred on the jugular notch, with one arm vertical and the other on the acromion.

Normal range: elevation and depression in the order of 37° and 8°. Elevation (shrugging) gives a measure of trapezius function, and may also be used to assess hand recovery after stroke. These movements are also impaired in any condition involving scapulothoracic movement.

Always screen the cervical spine in examining a case of shoulder pain; this is doubly important if shoulder movements are found to be normal.

Place one hand over the shoulder, with the middle finger lying along the acromioclavicular joint. Abduct the arm with the other hand. Detect any crepitus coming from the shoulder and locate its source (glenohumeral or acromioclavicular). Repeat while the arm is actively abducted, and if in doubt, auscultate. Clicking may arise from a number of sources, including scapular exostoses and coracoid impingement. (The latter may cause shoulder pain and coracoid tenderness.)

4.34. Rotator cuff examination (1):

Pathology in the rotator cuff may be suspected by the performance of abduction and the drop arm test (see Frames 4.14 and 4.16). Neer impingement sign: pain occurs when the shoulder is flexed to 90° and forcibly internally rotated. Neer impingement test: the test is repeated after injection of 10–15 mL of 1% xylocaine into the subacromial space, when less pain should be encountered if the pain is due to impingement of the rotator cuff against the acromion.

4.35. Rotator cuff examination (2): the Hawkins–Kennedy impingement sign:

the shoulder and elbow are both flexed to 90°, and the shoulder gently internally rotated until either the patient complains of pain or the scapula is felt to begin to move. The test is positive if there is complaint of pain.

4.36. Rotator cuff examination (3): the cross-body adduction test:

with the elbow extended, the shoulder is flexed to 90°. The examiner then adducts the arm across the chest. The test is described as being positive if the patient complains of pain. Three other tests (bringing the total to 8) may be taken into account when assessing the rotator cuff: these are the Speed test (Frame 4.45), the supraspinatus (Frame 4.48) and the infraspinatus tests when accompanied by pain (Frame 4.49).

4.37 Rotator cuff examination (4): assessing the test results:

the pathological basis of these eight tests is somewhat uncertain and controversial, but the following interpretations have been made:

From another point of view, when these tests indicate the likely presence of some shoulder cuff abnormality, it is claimed that a positive Neer test is the best indicator of a bursitis or partial shoulder cuff tear, while a painful arc, drop arm and positive infraspinatus test suggest a full rotator cuff tear.

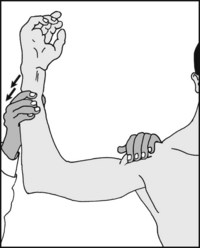

4.38. Anterior glenohumeral instability (1):

The apprehension test: Stand behind the patient (preferably seated) and abduct the shoulder to 90°. Slowly externally rotate the shoulder with one hand while pushing the head of the humerus forwards with the thumb of your other hand. Apprehension, fear or refusal to continue is evidence of chronic anterior instability of the shoulder. Repeat at 45° and 135° abduction. Pain only may be felt in minor subluxations.

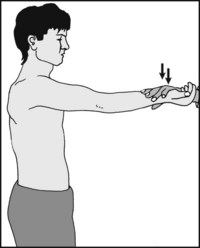

4.39. Anterior glenohumeral instability (2):

Relocation test: Repeat the apprehension test with the patient in the recumbent position; abduct and externally rotate the shoulder (1). When pain or apprehension first appear, press down on the upper arm (2). This will stabilise the head of the humerus in the glenoid at the time when subluxation is imminent, and should relieve any pain or apprehension. This, and the return of pain and apprehension on release of the downward pressure, is confirmatory of anterior instability.

4.40. Anterior glenohumeral instability (3):

Drawer test of Gerber and Ganz: Support the (supine) patient’s relaxed arm against your side, with his shoulder in 90° abduction, slight flexion and external rotation. Steadying the scapula with the thumb on the coracoid and the fingers behind, try to move the humeral head anteriorly with your other hand. Observe any movement, clicks and patient apprehension, and compare the sides: axial radiographs may be taken in confirmation during the procedure, which is sometimes performed under anaesthesia.

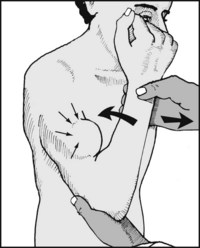

4.41. Posterior glenohumeral instability (1):

Drawer test: Where recurrent posterior dislocation is suspected, hold the relaxed, supine patient’s forearm with the elbow flexed and the shoulder in 20° flexion and 90° abduction. Place the thumb just lateral to the coracoid. Now internally rotate the shoulder and flex it to about 80°, pressing the humeral head backwards with the thumb; any backward displacement of the humeral head should be detected with the thumb, but X-ray confirmation may also be made.

4.42. Posterior glenohumeral instability (2):

The jerk test: With the patient’s shoulder over the edge of the examination couch (1), flex both the shoulder and elbow to 90° (2). With one hand on the elbow, push downwards (3) and attempt to sublux the humeral head posteriorly. If this occurs, indicating instability, a jerk or jump will be felt. If negative, repeat with the shoulder adducted and internally rotated.

4.43. Inferior glenohumeral instability:

The sulcus sign: With the patient standing, grasp the arm and pull it downwards. If there is inferior laxity then a depression will become obvious between the humeral head and the acromion. This is of greatest significance if absent or less on the good side, or if accompanied by pain and apprehension on the affected side. A positive test is usually indicative of multidirectional instability.

4.44. Biceps tendon instability test:

The shoulder is abducted to 90° and the elbow flexed to a right angle. The tendon is then located as it lies in the bicipital groove and, keeping the examining fingers in position, the patient’s shoulder is internally rotated. If the tendon is unstable it may be felt to move out of position; this may be accompanied by an audible click.

The Speed test: With the elbow fully extended and supinated, the shoulder is flexed to 90°. The patient is asked to resist as the examiner tries to extend the shoulder. There is complaint of pain during this manoeuvre if there is inflammation in the tendon. A positive Speed test may also be found where there is pathology in the shoulder cuff.

4.46. Integrity of the long head of biceps:

Support the patient’s elbow with one hand. Grasp his wrist and ask him to pull toward his shoulder while you resist this movement. If the long tendon of biceps is ruptured, the belly of biceps will appear globular in shape. Compare the two sides.

Ask the patient to try to keep the arm elevated in abduction while you press down on his elbow; look and feel for deltoid contraction. Traction injuries of the axillary nerve resulting in deltoid involvement are seen most frequently after dislocations of the shoulder. If axillary nerve palsy is suspected, test for sensory loss in the ‘regimental badge’ area on the lateral aspect of the arm.

4.48. The suprascapular nerve (1):

Supraspinatus: Palpate the scapula and identify its spine. Place the fingers of one hand above the spine, over the supraspinatus muscle. Steady the forearm with the other hand and ask the patient to attempt to abduct the arm against this resistance. If the suprascapular nerve is intact, the contraction of the supraspinatus should be easily felt. Repeat with the arm in 90° abduction: giving way on slight pressure is a sign of shoulder cuff pathology.

4.49. The suprascapular nerve (2):

Infraspinatus: In a similar manner palpate the infraspinatus, caudal to the spine of the scapula, while asking the patient to externally rotate the shoulder against resistance. Pain may occur in shoulder cuff pathology; paralysis of the muscle, with shoulder pain and weakness, may result from a ganglion in the greater scapular notch. (Confirm with an MRI scan.)

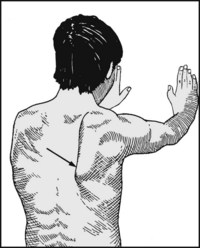

Where paralysis of serratus anterior is suspected, ask the patient to lean with both hands against a wall. Any tendency to winging of the scapula immediately becomes apparent.

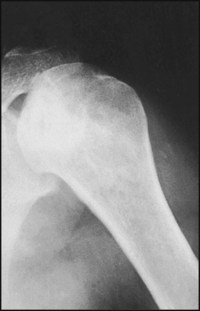

In screening the shoulder an anteroposterior projection is usually carried out, although additional views are highly desirable. This shows a typical normal film.

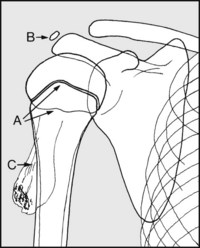

The standard shoulder projection is taken in recumbency. Examine the radiograph methodically by identifying (A) the glenoid, (B) the lateral border of the scapula, (C) the medial border of the scapula, (D) the spine of the scapula, (E) the acromion, (F) the coracoid. Note the relations of (G) the humeral head and (H) the clavicle to the glenoid and the acromion.

In the child or adolescent, do not mistake (A) the anterior and/or posterior margins of the epiphyseal plate for fracture or (B) the acromial ossification centre for a loose body. Note (C) the typical appearance of a simple exostosis (ossifying chondroma) of epiphyseal plate origin.

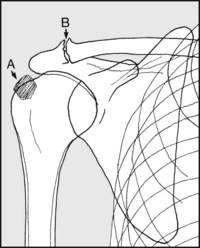

Calcification in the supraspinatus tendon in the upper part of the shoulder cuff has an amorphous appearance (A) and is characteristically situated. It may be symptom free. Note (B) arthritic changes in the acromioclavicular joint. Inferiorly projecting osteophytes are commonly associated with shoulder cuff pathology.

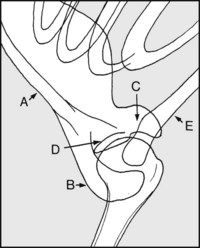

The axial lateral gives the most useful additional information, but is dependent on the patient being able to abduct the shoulder. It is very helpful in clarifying the relationships of the glenoid and humeral head; the lateral border of the scapula (A); the acromion and spine (B); the coracoid (C); the glenoid (D); and the clavicle (E).

4.57. Radiographs (7): additional projections (2):

Normal translateral (1): If the patient is not able to have the arm abducted, a translateral is another view that may be used to give additional information. Unfortunately detail is often poor, especially in the stout patient. (Some prefer an apical oblique projection, taken with the plate at 45° and the beam angled appropriately; this duplicates and foreshortens the features seen in Frame 4.52, but helps clarify the glenohumeral relationship.)

Normal translateral (2): Note (A) scapular spine; (B) glenoid; (C) coracoid; (D) acromioclavicular joints and superimposed clavicular shadows. Note the parabolic curve formed by the humeral shaft and the lateral border of the scapula. This is disturbed in most shoulder dislocations and subluxations.

4.59. Radiographs (9): additional projections (3):

In suspected recurrent dislocation of the shoulder an additional anteroposterior view should always be taken with the arm internally rotated. This may show a confirmatory defect in the posterolateral part of the humeral head (Hill–Sachs, or ‘hatchet head’ lesion). An axial lateral view will help to confirm this.

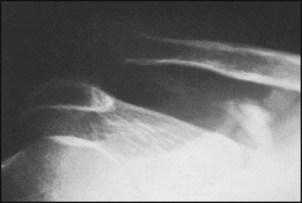

4.60. Radiographs (10): additional projections (4):

In cases of clicking or snapping shoulder, tangential views of the blade of the scapula will reveal any causal exostosis, particularly on the costal surface. (A) Acromion; (B) glenoid; (C) blade of scapula.

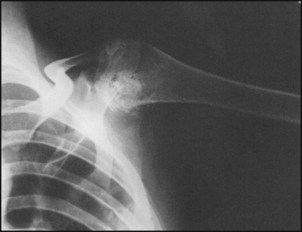

4.61. Radiographs (11): additional projections (5):

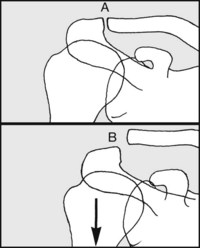

Where subluxation of the acromioclavicular joint is suspected, it is essential that the anteroposterior view of the shoulder is taken with the patient erect and holding a weight on the affected side. (A) Normal joint; (B) acromioclavicular dislocation.

4.62. Shoulder radiographs – examples of pathology (1):

There is a calcified mass over the humeral shaft: its pedicle is attached to the metaphysis.

Diagnosis: the appearances are of a simple exostosis (ossifying chondroma, enchondroma).

There is narrowing of the acromioclavicular joint space, some irregularity of the joint surfaces and a little lipping. There is a minimal degree of calcifying supraspinatus tendinitis also present.

There is marked narrowing of the glenohumeral joint space, with a large exostosis arising from the humeral head.

There is non-union in a fracture of the proximal humerus. The bone ends are rounded off and rather osteoporotic.

Diagnosis: history reveals that this has been a pathological fracture resulting from radionecrosis, following therapy for breast carcinoma.

There is irregularity of the humeral head, with patches of increased density.

Diagnosis: avascular necrosis of the head of the humerus. In this case the condition was due to caisson disease.

The arrow points to a fracture through the proximal humerus of a child. The bone is expanded and there is thinning of the cortex.

Diagnosis: this is a pathological fracture, in this case through a simple (unicameral) bone cyst.

4.69. Pathology (8): diagnosis:

this axial projection shows non-union in a fracture of the coracoid.

This axial radiograph shows an anterior subluxation of the shoulder associated with a defect in the humeral head.

Diagnosis: the findings confirm a clinical diagnosis of recurrent dislocation of the shoulder.

The humeral head has been replaced by a huge mass of poorly differentiated bone.

Diagnosis: the appearances are typical of osteoclastoma (giant cell tumour of bone), a locally malignant condition which may, however, on occasion become invasive and metastasise.

The head of the humerus has been destroyed.

Diagnosis: in this case the appearances are the result of a (malignant) chondrosarcoma.

The humerus and scapula show widespread patchy sclerotic changes.

Diagnosis: the appearances are typical of metastatic spread from a carcinoma of the prostate.

4.74. Pathology (13): diagnosis:

the radiograph shows a dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint. In addition, there is evidence of calcification in the haematoma which has resulted from the tearing of the conoid and trapezoid ligaments.

There is a large cavity in the humeral head containing a sequestrum; calcified pus is also present.

Diagnosis: the appearances are typical of tuberculosis of the shoulder joint.

There is gross distortion of the humeral head and the glenoid, with alteration of bone texture and destructive changes.

Diagnosis: the appearances are typical of Charcot’s disease.

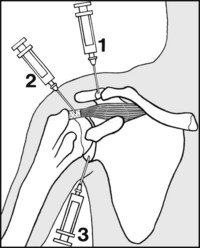

4.77. Special investigations (1):

Aspiration. Consider if pus is suspected. Method: with the patient supine, follow the clavicle laterally and find the coracoid, which lies about 5 cm obliquely below the acromioclavicular joint. Now rotate the arm, when you should be able to feel the head of the humerus. After local infiltration, pass a large-bore needle directly backwards into the joint below and just lateral to the coracoid.

4.78. Special investigations (2): Where there is shoulder pain related to movement and the source is uncertain, serial injections with local anaesthetic may be tried. Start with the acromioclavicular joint (1): if pain on movement is not relieved after 5–10 minutes, proceed to the upper part of the shoulder cuff (2); if this also fails, infiltrate the glenohumeral joint (3). This may be approached as detailed in the previous frame. Special investigations (3): Other investigations can include the following: Suspected infections