Chapter 101 Shock and cardiac disease in children

Most cases of shock in childhood are caused by hypovolaemia (Table 101.1) or sepsis. The causes, clinical course, management and complications of shock differ from those in adults: severe diarrhoeal disease and congenital abnormalities are common in childhood but abdominal sepsis, pancreatitis and obstructive vascular disease are uncommon.

Table 101.1 Causes of hypovolaemic shock in childhood

| Water deprivation (absolute or relative to losses) |

The following factors affect the epidemiology of shock in children:

SMALLER BODY FLUID COMPARTMENTS

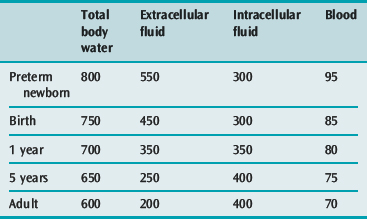

A small volume of blood or diarrhoeal fluid loss, or of fluid leakage into the extravascular space may represent a large percentage loss of blood or extracellular fluid (ECF) volume in a small child (Table 101.2).

IMMATURE IMMUNE SYSTEM IN INFANTS AND TODDLERS2

Antibody response to bacterial polysaccharide capsular antigens (e.g. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus spp. and Neisseria meningitidis) remains poor in the preschool years. Low IgG concentrations, immunological naivety and reduced natural killer (NK) cell activity predispose young children to frequent viral infections, and the newborn to severe herpes simplex infection.3

Reduced cytokine production, especially in the immunologically naive, may alter the features and duration of the shock syndrome, including the ability to develop a fever, and causes deficiency in most T-cell functions, including cytotoxicity and augmentation of B-cell differentiation.4

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The pathophysiology of shock is described in Chapter 11 which should be read in conjunction with this chapter. The following aspects of a child’s physiology affect the response to insults.

IMMATURE CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM5,6

LESS DIASTOLIC COMPLIANCE THAN THE ADULT HEART

MORE TOLERANT OF HYPOXAEMIA

Although the infant heart has fewer mitochondria per gram of tissue, and a lower oxidative capacity, it has a lower oxygen demand per gram, larger glycogen reserves and a higher capacity for anaerobic glycolysis.7 Glucose is the major myocardial energy source (rather than long chain fatty acids as in older children) and hypoglycaemia causes severe myocardial depression.

IMMATURE AUTONOMIC INNERVATION

The infant myocardium has fewer β-receptors, more α-receptors, and is more sensitive to noradrenaline (norepinephrine) than the adult. Stimulation of myocardial α-receptors in the infant is more likely to cause tachycardia than bradycardia.8

HIGH PULMONARY VASCULAR RESISTANCE8

At birth, after the first breaths are taken, the smooth muscle cells gradually relax and become more fusiform in shape. Pulmonary vascular resistance falls immediately, then gradually declines to adult levels by 6–8 weeks of age, and smooth muscle bulk falls to adult levels by 3–4 months.9 In the presence of lung disease, high pulmonary venous pressures (e.g. due to aortic stenosis or stenosis of the pulmonary veins) or large left-to-right shunts (e.g. ventricular septal defect (VSD) or truncus arteriosus), the high pulmonary vascular resistance and the extensive and bulky vascular smooth muscle fail to decline normally. The infant is then vulnerable to episodes of acute right heart failure whenever the pulmonary vascular resistance increases abruptly.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF SHOCK IN CHILDHOOD

HYPOVOLAEMIC SHOCK (SEE Table 101.1)

The child may have a history of fluid or blood loss, reduced fluid intake or bowel-related illness. Signs of dehydration (see Chapter 99), external bleeding or haematoma may be present. The presence of hypovolaemic shock implies a blood volume deficit greater than 30 ml/kg.

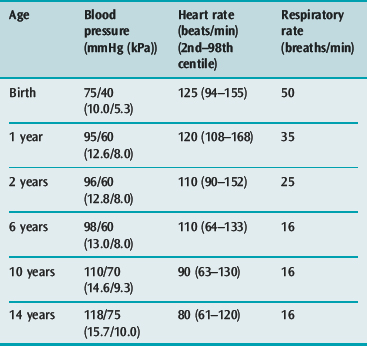

Signs of homeostatic compensation, such as tachycardia (Table 101.3), narrow pulse pressure, cool mottled limbs and slow capillary refill usually precede the onset of hypotension, which tends to occur late (after loss of 15–20% of blood volume) and precipitously in young children. In severe shock of any cause, signs of multiple organ hypoperfusion (e.g. oliguria of less than 0.5 ml/kg per hour, lethargy or coma, hypothermia, tachypnoea and increasing lactic or other metabolic acidosis) are found. Bleeding due to disseminated intravascular coagulation and liver dysfunction may occur in the first 6 hours.

Investigations (see Table 101.4) include:

| All shocked children |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ECG, electrocardiogram; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

CARDIOGENIC SHOCK

Combinations of signs specific to individual congenital heart lesions are described below. Such signs when present (e.g. absent femoral pulses in aortic coarctation, or skull, liver or renal bruits of arteriovenous fistulae) may indicate the cause of the shock (Table 101.5), while diagnostically useful murmurs are not always present.

Investigations (see Table 101.4) should include:

SEPTIC SHOCK

Severely septic children are often hypothermic rather than febrile.

As shock progresses, myocardial depression by endotoxin, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (see Chapter 11) decreases the cardiac output earlier than is the case in adults, as the less compliant infant ventricle cannot dilate to sustain the stroke volume in the face of a reduced ejection fraction.11,12 Furthermore, the rapid and severe capillary leak that is characteristic of paediatric sepsis leads to hypovolaemia in the underresuscitated child, further reducing preload and cardiac output. For this reason, septic children often respond well to aggressive fluid resuscitation (> 60 ml/kg in the first hour). Peripheral oedema caused by leakage of proteinaceous fluid from injured capillary endothelia exacerbates cellular hypoxia by increasing the diffusion distance for oxygen between capillaries and cells.

MULTIPLE ORGAN FAILURE IN SHOCKED CHILDREN

DISTRIBUTIVE SHOCK

The main features are hypotension, vasodilatation and hypovolaemia due to plasma leakage from capillaries. The child’s extremities are warm and pink, the blood pressure is low and the pulse pressure is wide. There is tachycardia, oliguria and stupor. Other evidence of anaphylaxis (wheezing, urticaria, swollen face or tongue), spinal cord injury (bradycardia, quadriparesis, lax anal sphincter) or drug intoxication (history, tablets, coma out of proportion to shock) may be present (Table 101.6).

MANAGEMENT

The child’s airway, breathing (see Chapter 98) and circulation should be secured during the initial assessment. The priorities in management of the circulation are to achieve:

ADEQUATE PERFUSION OF THE BRAIN AND HEART

This requires systolic and diastolic blood pressures of 80% of normal for age (see Table 101.3), achieved by aggressive early blood volume expansion and by pressor drugs. The conscious state is the best index of adequate brain perfusion, while improved coronary perfusion is shown by rising blood pressure with falling central venous pressure.

Preload

Pulmonary artery catheterisation for measurement of wedge pressure and cardiac output is rarely justified in children: evidence that it improves outcome is lacking,15 and side-effects occur commonly.16 Non-invasive monitoring of left and right ventricular preload by transthoracic echocardiography may be more useful than atrial pressure measurement, in that it removes the confounding factors of diastolic compliance and atrioventricular (AV) valve dysfunction, but it is subjective and operator dependent.17

Systemic vascular resistance

In septic or hypovolaemic shock, infusion of noradrenaline (0.05–2.0 μg/kg per min) should be started (via an intraosseous cannula when no central venous cannula is in place) if volume expansion does not achieve 80% of normal systolic blood pressure for age within 10 minutes. In septic shock, vasopressin (0.0003–0.0006 U/kg per min), the action of which does not depend on downregulated α1-receptors, may be used to reduce the dose of noradrenaline required. Vasopressin deficiency occurs commonly in septic shock18 and in irreversible shock of other causes.19

Contractility

If the blood pressure then remains low despite CVP = 12 mmHg or ‘adequate’ LV filling on transthoracic echo, an inotrope such as adrenaline (0.05–2.0 μg/kg per min), dobutamine or dopamine (5–15 μg/kg per min) should be added. Dobutamine and dopamine downregulate β-adrenergic receptors, and dopamine depletes myocardial noradrenaline stores, so the dose of these drugs should be minimised as soon as possible. β-Agonists increase oxygen consumption (and therefore oxygen demand) by increasing free fatty acid cycling and by increasing glycogenolysis and glycolysis.20 Dopamine suppresses prolactin, thyroid-stimulating hormone and growth hormone secretion in infants and children.21

ADEQUATE PERFUSION OF KIDNEYS, LIVER AND GUT

Bowel and liver ischaemia in a shocked child impairs detoxification of drugs and toxic metabolites and may increase the risk of bacteraemia and endotoxaemia of bowel origin.22 Hypovolaemia and low cardiac output must be corrected by blood volume expansion and inotropic drugs such as dobutamine. Vasoconstricting drugs (vasopressin, noradrenaline and dopamine doses > 5 μg/kg per min) should be reduced or stopped once heart and brain perfusion are secured.

Urine output > 0.5 ml/kg per hour and a normal (or falling) plasma creatinine concentration are the best indices of adequate renal perfusion. Monitoring of splanchnic perfusion remains unreliable. Gastric pH and gastric–arterial PCO2 difference correlate somewhat with outcome in septic children (though not as well as plasma lactate)23 and are not consistently improved by measures to restore bowel perfusion.24 Oesophageal–arterial PCO2 difference25 and near-infrared spectroscopy of the liver26 may offer more accurate monitoring of the adequacy of splanchnic blood flow.

ADEQUATE PERFUSION OF MUSCLE AND OTHER TISSUES

Further volume expansion and infusion of vasodilators such as milrinone may be needed to improve circulation to these tissues in shock states where myocardial depression is prominent, provided an adequate blood pressure (80% normal for age; see Table 101.3) can be sustained. Maintaining a supranormal cardiac output and oxygen delivery has not been shown to improve survival in paediatric shock, although the ability to do so may predict survival.

In the absence of a pulmonary artery catheter, the adequacy of upper or lower body blood flow is conventionally assessed by monitoring changes in central venous saturation27 and plasma lactate, though the oxygen excess factor Ω (SaO2/(SaO2 – SvO2) has been used in children with intracardiac shunts.28

Afterload reduction in cardiogenic shock

Vasoconstrictors and blood transfusion (to achieve a haemoglobin concentration of 120 g/l) may be required at first to ensure adequate coronary and cerebral perfusion pressure. When blood pressure is adequate (see Table 101.3), the cardiac output may be improved by afterload reduction. Short-acting drugs such as milrinone or sodium nitroprusside (SNP) are preferable.

Inhaled nitric oxide (NO) 1–10 ppm via the ventilator circuit may improve RV output in children with cardiogenic shock due to pulmonary hypertension (primary or after cardiac surgery or in persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn). Sildenafil and bosentan have been shown to reduce pulmonary vascular resistance and to permit weaning from NO in this group of children.29

After appropriate samples are taken for investigations (see Table 101.4), possible sepsis is treated aggressively with appropriate antibiotics (Table 101.7), replacement of invasive lines and drainage of collections of pus.

Table 101.7 Initial antibiotic therapy in children with septic shock

| Up to 8 weeks of age |

Controversial measures

HEART FAILURE IN CHILDREN

In cardiac failure, the cardiac output is insufficient to meet the metabolic needs of the tissues without development of abnormally high ventricular end-diastolic volumes.38

Table 101.8 shows the main causes of heart failure in children. In many cases, several factors combine to produce heart failure (e.g. sepsis plus valve regurgitation and amiodarone).

Table 101.8 Common causes of heart failure from infancy to adolescence

| Heart failure presenting at birth |

AV, arteriovenous; LCAD, long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

PRESENTING SIGNS

In childhood, heart failure may present with growth failure. Feeding is slow and may cause sweating and dyspnoea. Useful signs are tachypnoea, cardiomegaly, hepatomegaly, gallop rhythm, tachycardia and cool, mottled extremities. There may be clinical and X-ray signs of lung congestion, oedema and air trapping (due to airway compression by distended blood vessels and airway mucosal oedema: seen in large left-to-right shunts such as VSD). In infants, the JVP is a difficult sign to elicit. The liver enlarges rapidly as the right atrial pressure increases, and oedema is often non-pitting, and located in the eyelids and the dorsum of the hands and feet.39

INVESTIGATIONS

After a detailed history and clinical examination, investigations include:

MANAGEMENT40,41

CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

Children critically ill with congenital heart disease (CHD) often require urgent resuscitation before a definitive structural diagnosis is made. The appropriate management then depends on the mode of presentation. A paediatric cardiologist should be consulted immediately about all such children. Management of acute postoperative deterioration depends on the underlying condition, nature of surgery and cause of deterioration.

Congenital heart disease in children may present in the following ways.

SHOCK IN THE FIRST FEW DAYS OF LIFE47

Emergency management48 consists of prostaglandin E1 infusion (start at 10 ng/kg per min and increase to 25 if necessary) to provide aortic blood flow from the pulmonary artery by opening the ductus arteriosus, dopamine infusion, NaHCO3 1 mmol/kg i.v. over 1 hour to correct metabolic acidosis, and mechanical ventilation (to reduce work of breathing, maintain normocarbia and prevent apnoea due to the PGE1). Hypocarbia and a high FiO2 should be avoided as they reduce pulmonary vascular resistance and divert blood flow to the lungs, thereby reducing systemic blood flow. Normoglycaemia and normocalcaemia should be maintained.

ACYANOTIC HEART FAILURE

IN THE FIRST WEEK OF LIFE47

Emergency management includes oxygen, diuretics and fluid restriction (to 50% of maintenance requirements; see Chapter 99). In severe failure, mechanical ventilation and inotropic drug infusion (see above) are started, and the child is transferred to a paediatric cardiac centre. When femoral pulses are absent or if aortic stenosis is suspected, i.v. infusion of PGE1 (5–25 ng/kg per min) is started.

CYANOSIS

CYANOSIS WITH PULMONARY OLIGAEMIA ON CHEST X-RAY

Emergency management47,49

Beyond 1 month of age

If the PaO2 is less than 30 mmHg (4.0 kPa), or if cyanotic spells occur in a child with tetralogy of Fallot despite plasma volume expansion and oral β-blockers, an urgent Blalock–Taussig shunt is needed. Urgent treatment of Fallot spells consist of high FiO2, knee–chest (older child) or legs raised (infant) position, 0.9% saline infusion 20 ml/kg and i.v. morphine 0.1 mg/kg. If these measures fail, then esmolol (0.5 mg/kg i.v. then infusion of 50–200 μg/kg per min) may be needed to reduce subpulmonary obstruction in Fallot’s tetralogy. Inotropic drugs and vasodilators should be avoided.

ARRHYTHMIAS IN CHILDREN50

ATRIOVENTRICULAR BLOCK52 (Table 101.9)

Often asymptomatic, but may present with fatigue, syncope or cardiac failure.

MANAGEMENT

SUPRAVENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA (SVT)

RE-ENTRANT SVT

In older children and adolescents, a re-entrant pathway may exist in the peri-AV node area, and is sometimesassociated with congenital heart lesions such as Ebstein’s anomaly, tricuspid atresia and AV canal defects, as well as post cardiac surgery, myocarditis, drugs, sepsis, acidosis and catecholamine administration.

Management

Infants

JUNCTIONAL ECTOPIC TACHYCARDIA (JET)50,52

Management

JET is usually resistant to vagal manoeuvres, adenosine and overdrive pacing.

VENTRICULAR ECTOPIC BEATS AND VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA

Ventricular tachycardia (VT)51 is uncommon in childhood, but may present as syncope, poor feeding (in infants) or heart failure. The rate is 120–300 beats/min. The QRS axis is different from that of the underlying sinus rhythm. QRS duration is usually (but not always) prolonged (> 0.08 seconds). Supraventricular tachycardia with aberrant conduction is rare in children: more than 90% of wide-complex tachycardias in children are VT. Fusion or capture beats, AV dissociation and new bundle branch block also favour the diagnosis of VT.

1 Friis-Hansen B. Body water compartments in children: changes during growth and related changes in body composition. Pediatrics. 1961;28:169-181.

2 Lawton AR, Crowe JE. Ontogeny of immunity. In: Stiehm ER, Ochs HD, Winkelstein JA, editors. Immunologic Disorders in Infants and Children. 5th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:3-19.

3 Roberton DM. The child who is immunodeficient. In: Robinson MJ, Roberton DM, editors. Practical Paediatrics. 4th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998:392-399.

4 Lewis DB, Wilson CB. Developmental immunology and role of host defences in neonatal susceptibility to infection. In: Remington JS, Klein JO, editors. Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant. 4th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995:20-98.

5 Epstein D, Wetzel RC. Cardiovascular physiology and shock. In: Nichols DG, Ungeleider RM, Spevak PJ, et al, editors. Critical Heart Disease in Infants and Children. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2006:17-72.

6 Mahony L. Development of myocardial structure and function. In: Allen HD, Gutgesell HP, Clark EB, et al, editors. Moss and Adams’ Heart Disease in Infants, Children and Adolescents. 6th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2001:24-40.

7 Williams CE, Mallard C, Tan W, et al. Pathophysiology of perinatal asphyxia. Clin Perinatol. 1993;20:305-325.

8 Anderson PAW, Kleinman CS, Lister G, et al. Cardiovascular function during development and the response to hypoxia. In: Polin RA, Fox WW, Abman SH, editors. Fetal and Neonatal Physiology. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:635-669.

9 Martin LD, Nyhan D, Wetzel RC. Regulation of pulmonary vascular resistance and blood flow. In: Nichols DG, Ungeleider RM, Spevak PJ, et al, editors. Critical Heart Disease in Infants and Children. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2006:73-112.

10 Davignon A, Rautaharju P, Boisselle E, et al. Normal ECG standards for infants and children. Pediatr Cardiol. 1980;1:123-152.

11 Carcillo JA. The failing cardiovascular system in sepsis. In: Chang AC, Towbin JA, editors. Heart Failure in Children and Young Adults. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006:416-427.

12 Kumar A, Haery C, Parrillo JE. Myocardial dysfunction in septic shock. Crit Care Clin. 2000;16:251-287.

13 Poelaert J, Declerck C, Vogelaers D, et al. Left ventricular systolic and diastolic function in septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:553-560.

14 Vincent JL. New therapeutic implications of anticoagulation mediator replacement in sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(Suppl 9):S83-85.

15 Tibby SM, Murdoch IA. Measurement of cardiac output and tissue perfusion. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2002;14:303-309.

16 Thompson AE. Pulmonary artery catheterization in children. New Horizons. 1997;5:244-250.

17 Levy RJ, Deutschman CS. Evaluating myocardial depression in sepsis. Shock. 2004;22:1-10.

18 Holmes CL, Patel BM, Russell JA, et al. Physiology of vasopressin relevant to management of septic shock. Chest. 2001;120:989-1002.

19 Robin JK, Oliver JA, Landry DW. Vasopressin deficiency in the syndrome of irreversible shock. J Trauma. 2003;54:S149-154.

20 Romijn JA, Coyle EF, Sidossis LS, et al. Regulation of endogenous fat and carbohydrate metabolism in relation to exercise intensity and duration. Am J Physiol. 1993;265(3 Pt 1):E380-391.

21 Van den Berghe G, de Zegher F, Lauwers P. Dopamine suppresses pituitary function in infants and children. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:1747-1753.

22 Lichtman SM. Bacterial translocation in humans. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33:1-10.

23 Duke TD, Butt W, South M. Predictors of mortality and multiple organ failure in children with sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:684-692.

24 Marshall JC. An intensivist’s dilemma: support of the splanchnic circulation in critical illness [comment]. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1637-1638.

25 Totapally BR, Fakioglu H, Torbati D, et al. Esophageal capnometry during hemorrhagic shock and after resuscitation in rats. Crit Care. 2003;7:79-84.

26 Schulz G, Weiss M, Bauersfeld U, et al. Liver tissue oxygenation as measured by near-infrared spectroscopy in the critically ill child in correlation with central venous oxygen saturation. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:184-189.

27 Marx G, Reinhart K. Venous oximetry. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006;12:263-268.

28 Charpie JR, Dekeon MK, Goldberg CS, et al. Postoperative hemodynamics after Norwood palliation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:198-202.

29 Beghetti M. Current treatment options in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension and experiences with oral bosentan. Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;3:16-24.

30 Annane D, Bellissant E, Bollaert PE, et al. Corticosteroids for treating severe sepsis and septic shock. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (Issue 1):2004. Art. No. CD002243 http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD002243/frame.html

31 Bilgin K, Yarami A, Haspolat K, et al. A randomized trial of granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor in neonates with sepsis and neutropenia [see comment]. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):36-41.

32 Alejandria MM, Lansang MA, Dans LF, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for treating sepsis and septic shock. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (Issue 1):2002. Art. No. CD001090 http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD001090/frame.html

33 Levin M, Quint PA, Goldstein B, et al. Recombinant bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (rBPI21) as adjunctive treatment for children with severe meningococcal sepsis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:961-967.

34 Mohan P, Brocklehurst P. Granulocyte transfusions for neonates with confirmed or suspected sepsis and neutropaenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (Issue 4):2003. Art. No. CD003956 http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD003956/frame.html

35 Giroir B, Goldstein B, Nadel S, et al. The efficacy of drotrecogin alfa (activated) for the treatment of pediatric severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2006;33:A152.

36 Dimmick S, Badawi N, Randell T. Thyroid hormone supplementation for the prevention of morbidity and mortality in infants undergoing cardiac surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (Issue 3):2004. Art. No. CD004220 http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD004220/frame.html

37 Leclerc FMD, Leteurtre SMD, Cremer RMD, et al. Do new strategies in meningococcemia produce better outcomes? Crit Care Med. 2000;28(9 Suppl):S60-63.

38 Braunwald E. Heart failure. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 15th edn. New York: McGraw Hill; 2001:1318-1329.

39 Altman CA, Kung G. Clinical recognition of congestive heart failure in children. In: Chang AC, Towbin JA, editors. Heart Failure in Children and Young Adults. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006:201-210.

40 Chang AC, Towbin JA, editors. Heart Failure in Children and Young Adults. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006.

41 Kay JD, Colan SD, Graham TPJr. Congestive heart failure in pediatric patients. Am Heart J. 2001;142:923-928.

42 Dickerson HA, Chang AC. Diuretics. In: Chang AC, Towbin JA, editors. Heart Failure in Children and Young Adults. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006.

43 Kageyama K, Shime N, Hirose M, et al. Factors contributing to successful discontinuation from inhaled nitric oxide therapy in pediatric patients after congenital cardiac surgery. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5:351-355.

44 De Luca L, Colucci WS, Nieminen MS, et al. Evidence-based use of levosimendan in different clinical settings. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1908-1920.

45 Packer M, Fowler MB, Roecker EB, et al. Effect of carvedilol on the morbidity of patients with severe chronic heart failure: results of the carvedilol prospective randomized cumulative survival (COPERNICUS) study. Circulation. 2002;106:2194-2199.

46 Dent CL, Nelson DP. Low cardiac output in the intensive care setting. In: Chang AC, Towbin JA, editors. Heart Failure in Children and Young Adults. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006.

47 Penny DJ, Shekerdemian LS. Management of the neonate with symptomatic congenital heart disease. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001;84:F141-145.

48 Lang P, Fyler DC. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome, mitral atresia and aortic atresia. In Keane JF, Lock JE, Fyler DC, editors: Nadas’ Pediatric Cardiology, 2nd edn., Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006.

49 Breitbart RE, Fyler DC. Tetralogy of Fallot. In Keane JF, Lock JE, Fyler DC, editors: Nadas’ Pediatric Cardiology, 2nd edn., Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006.

50 Fish FA, Benson DWJ. Disorders of cardiac conduction and rhythm. In: Allen HD, Gutgesell HP, Clark EB, et al, editors. Moss and Adams’ Heart Disease in Infants, Children and Adolescents. 6th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001:482-533.

51 Vetter V, Arrhythmias. Moller JH, Hoffman JIE, editors. Pediatric Cardiovascular Medicine. Churchill Livingstone, New York, 2000;833-883.

52 Kanter RJ, Carboni MP, Silka MJ. Pediatric arrhythmias. In: Nichols DG, Ungerleider RM, Spevak PJ, et al, editors. Critical Heart Disease in Infants and Children. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2006:207-241.