OCCIPITAL EPILEPSY OF GASTAUT

Late-onset childhood occipital epilepsy (Gastaut type) in its pure form is a self-limited epilepsy, presenting with focal seizures of childhood or adolescence. It is a distinct syndrome with unique seizure semiology, characteristic EEG findings, and, for the most part, favorable prognosis. Importantly, there are structural epilepsies that can present in a similar fashion and must be distinguished with brain imaging.

Gibbs and Gibbs described a case in 1952 followed by other reports (1). Initially, there was some diagnostic confusion as to whether the features were more consistent with migraine or epilepsy (2). Based upon careful and clever electrophysiologic observations, the epilepsy opinion prevailed (3,4). Gastaut identified a series of patients and the international community adapted the current nomenclature, at least in part, to allow differentiation from Panayiotopoulos syndrome, which typically presents at an earlier age and has very different clinical characteristics (5–7).

Epidemiology

Occiptial epilepsy of Gastaut is rare, constituting only 0.3% of all children with newly diagnosed afebrile seizures (8); a recent report suggests it accounts for only 2.8% of all self-limited epilepsies with focal seizures (9).

Demographic Information

There is no gender predominance, and a wide age range from infancy to late adolescence was originally suggested by Gastaut (5), but the peak age of onset is at 8.5 years (10).

Clinical Manifestations

Elementary visual hallucinations are the commonest and most characteristic ictal symptom. They often consist of small multicolored circular patterns in the periphery that enlarge, multiply, and move to the other side. These visual symptoms are usually brief, ranging from only a few seconds to less than 3 minutes, but may be frequent, occurring from multiple daily attacks to attacks once a month.

The second commonest visual manifestation is ictal blindness. This may involve only a quadrant, one half of the visual field, or may be total. A sensation of eye movement may occur as a progression of the visual auras.

If the seizure progresses, deviation of the eyes with ipsilateral turning of the head is the most common nonvisual symptom (5,11–13). In a minority of patients, it is also possible to observe forced eyelid closure with blinking. This signals an impending hemiconvulsion or a secondarily generalized tonic–clonic seizure. Hemiconvulsions or secondarily generalized tonic–clonic seizures can also occur after elemenatary visual hallucinations or other ictal symptoms.

Rarely is the ictal semiology consistent with a temporal lobe focus; if present, a structural lesion should be excluded.

Postictal headache is a consistent symptom in one-third of children, even without preceding convulsions (5,10,14). Headaches typically begin about 5 to 10 minutes after the end of the visual hallucinations. The duration and severity of the headache is often proportional to the duration and severity of the preceding seizure, and it may often have migraine features.

Etiology

Like the other self-limited epilepsies with focal seizures, or the benign childhood seizure susceptibility spectrum, the cause of the epilepsy is unknown. There are some reports of multiple members within a family presenting with late-onset childhood occipital epilepsy—Gastaut type (15–17). On the other hand, twin studies did not show a markedly increased concordance, making it likely that factors other than genetics contribute to the clinical susceptibility (18). Like other self-limited epilepsies with focal seizures, the interictal discharges appear to be in an autosomal-dominant fashion with variable penetrance (15).

Electroencephalography

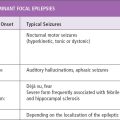

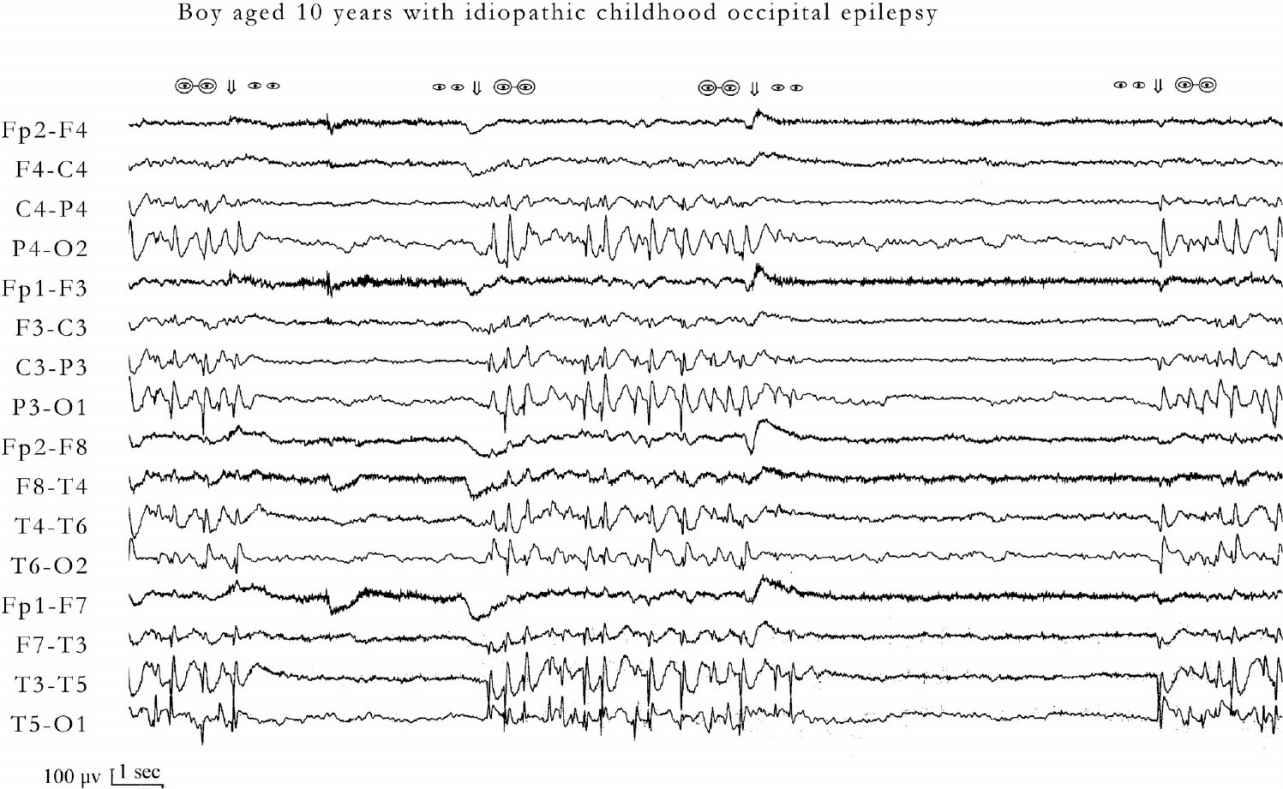

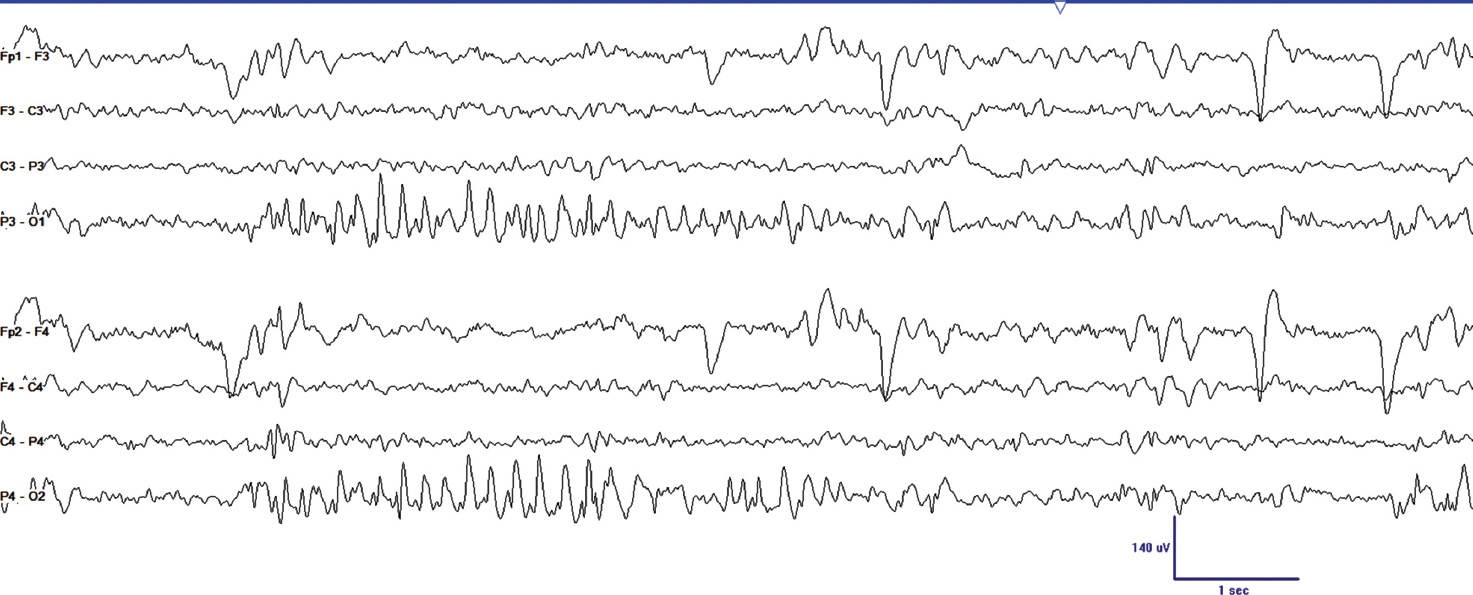

The EEG shows occipital interictal epileptiform discharges with or without fixation-off sensitivity (Figure 24.1). Occipital spikes, in routine recordings, occur when the eyes are closed, because of fixation-off sensitivity (Figure 24.2). Occipital paroxysms are totally inhibited by fixation and central vision. Occipital paroxysms may also be suppressed during various neuropsychologic conditions (19). Random occipital spikes, sometimes occurring only during sleep and normal EEG, are frequent. EEG abnormalities may be disproportional to clinical severity. Age-dependent occipital spikes frequently occur in organic brain diseases with or without seizures, and in children with congenital and early-onset visual deficits, or in normal, mainly preschool-aged children.

The interictal EEG patterns of occipital epilepsy of Gastaut with elementary visual hallucinations are much more diverse than it is generally reported (20). Of 19 patients with this syndrome, only four had the classical occipital paroxysms—one in combination with generalized discharges and photoparoxysmal and spontaneous occipital spikes. Five patients had photoparoxysmal occipital spikes, alone (two patients) or in combination with spontaneous occipital spikes (one patient) or with spontaneous occipital spikes and generalized discharges (two patients). Two patients had spontaneous occipital spikes—one in combination with C4, Cz, and C3 spikes. Five patients had consistently normal EEGs, whereas three others had nonspecific (two patients) or generalized (one patient) photoparoxysmal discharges. It should also be emphasized that fixation-off sensitivity with or without occipital paroxysms is not specific for any syndrome, and may also occur in adults and patients without idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut (21–23).

Focal occipital seizures with positive signs and no impairment of awareness are characterized by fast spike activities that, when slowing down, can reach neighboring regions of the scalp. While the amplitude of the ictal activity increases, the frequency of repetition lessens. In oculoclonic seizures, spikes and spike waves are typical of the last part of the discharge. There are usually no postictal abnormalities. Phosphenes are related to the fast spike activity, often quickly involving the two hemispheres; on the contrary, when the discharge is slower, complex hallucinations may take place. In oculoclonic seizures, a localized ictal fast spike rhythm may be observed before the deviation of the eyes. EEG findings during temporary blindness are characterized by pseudoperiodic slow waves and spikes, which differs from that of positive visual hallucinations (24).

FIGURE 24.1 Occipital paroxysms with fixation off sensitivity of a 10-year-old boy with idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy. Occipital paroxysms occur immediately after and as long as fixation and central vision are eliminated by any means (eyes closed, darkness, plus 10 spherical lenses, Ganzfeld stimulation). Under these conditions, even in the presence of light, eye opening does not inhibit the occipital paroxysms. Conversely, occipital paroxysms are totally inhibited by fixation and central vision. Symbols of eyes open without glasses indicate conditions in which fixation is possible. Symbols of eyes with glasses indicate conditions in which central vision and fixation are eliminated. At age 18 years, he is entirely normal and is not receiving medication.

FIGURE 24.2 This segment of EEG was obtained on an 11-year-old girl who began having seizures at 8 years of age. She described colored lights moving across her visual field, and observers noted these were followed by generalized convulsions. She had not had a seizure for 6 months on levetiracetam when this study was performed. Note the abundant occipital paroxysms that occur shortly after eye closure.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Other than EEG, a high resolution MR is indicated in most cases to exclude static or progressive occipital lesions (25).

Prognosis

In contrast to the other forms of self-limited epilepsies with focal seizures described in the preceding chapters, the prognosis with late-onset childhood occipital epilepsy of the Gastaut type is less certain. This may be due to the inadvertent comingling of patients with subtle occipital structural lesions in the various series. Still, remission can be expected in more than 60% of patients (1,10,11). In one study, intellectual function and school performance was tested and, for the most part, no significant differences were found between patient and control groups; however, the patients’ performance scores were lower in attention and memory (26). In another study, children with self-limited occipital epilepsy demonstrated slight selective impairment in visuospatial processing in those with a high number or seizures (27).

Management

Most authorities recommend treatment of late-onset childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut because of the frequency of the seizures and the possibility of secondary generalization. Reported effective agents have included carbamazepine and levetiracetam (10,21).

Summary

Occipital epilepsy of Gastaut is a pure occipital epilepsy that typically presents in late childhood or early teenage years. Seizures are typically heralded by brief but daily elementary visual phenomena that may progress less frequently to hemiconvulsive or secondarily generalized convulsive seizures. Postictal headache occurs at least one-third of the time with migrainous features. The EEG demonstrates stereotyped occipital spikes with fixation-off sensitivity. The prognosis is generally favorable, particularly if structural causes of occipital epilepsy are excluded and treatment of the less severe type often responds promptly to medication.

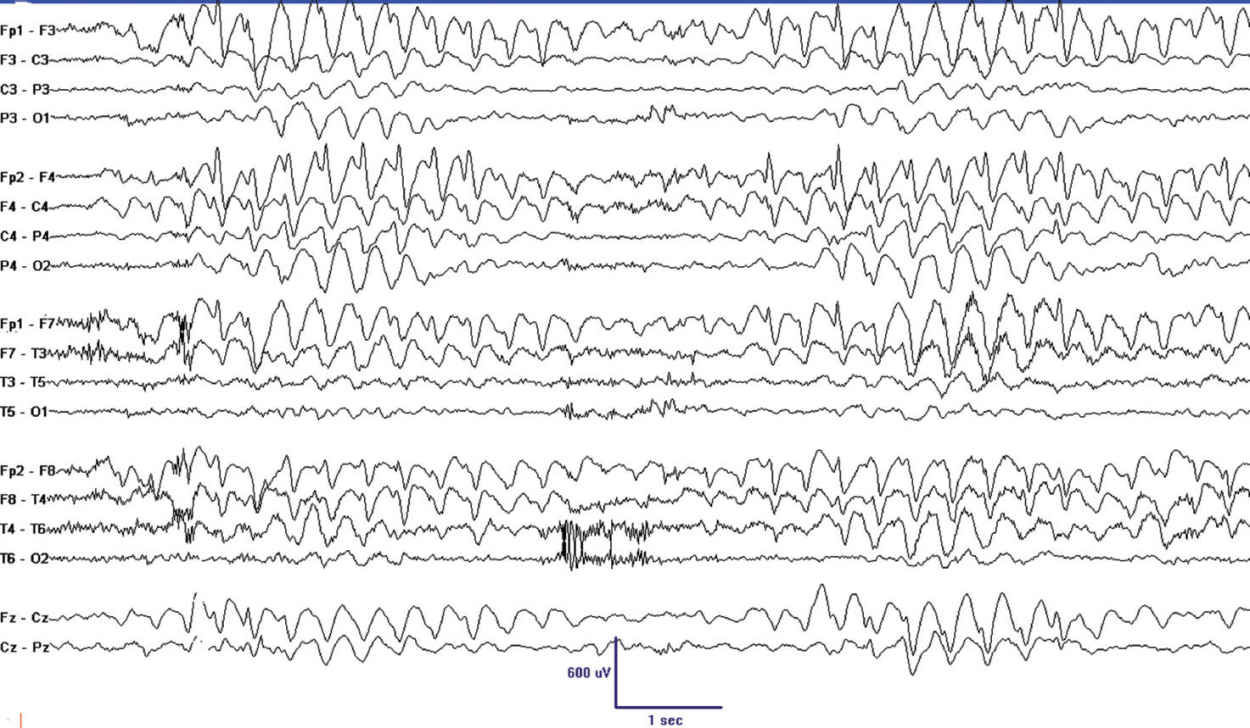

FIGURE 24.3 This 10-year-old girl had several isolated focal seizures with asymmetric tonic posture and slight clonus. She was seizure-free on levetiracetam when this EEG was obtained. Note the abundant frontal spikes and associated rhythmic slowing that is more pronounced in the right.

BENIGN CHILDHOOD EPILEPSY WITH AFFECTIVE SYMPTOMS

Benign childhood epilepsy with affective symptoms has been infrequently reported but has very distinctive features. Onset is between 2 to 9 years with no gender preference. Seizures manifest with apparent terror with screaming, autonomic changes, oral and other automatisms, speech arrest, and mild impairment of consciousness (28). Attacks are usually brief, less than 2 min, and may occur multiple times daily, either in wakefulness or sleep. One-fifth of patients have had febrile seizures and some have infrequent rolandic seizures. The EEG shows high-amplitude fronto-temporal and parieto-temporal interictal epileptiform discharges that are exaggerated by sleep. Response to treatment is excellent and remission commonly occurs within 2 years from onset. As with other self-limited epilepsies, behavioral problems may be present, particularly during the active phase of the disease.

BENIGN CHILDHOOD FOCAL SEIZURES ASSOCIATED WITH FRONTAL SPIKES

There have been scattered reports of favorable outcomes in children with focal seizures and frontal or midline spikes, but no systematic studies have been published (29,30) (Figure 24.3).

REFERENCES

1. Gibbs FA, Gibbs EL. Atlas of Electroencephalography. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1952:214–290.

2. Camfield PR, Metrakos K, Andermann F. Basilar migraine, seizures, and severe epileptiform EEG abnormalities. Neurology. 1978;28(6):584–588. doi:10.1212/WNL.28.6.584.

3. Panayiotopoulos CP. Basilar migraine? Seizures, and severe epileptic EEG abnormalities. Neurology. 1980;30(10):1122–1125. doi:10.1212/WNL.30.10.1122.

4. Panayiotopoulos CP. Inhibitory effect of central vision on occipital lobe seizures. Neurology. 1981;31(10):1330–1333. doi:10.1212/WNL.31.10.1331.

5. Gastaut H. Benign spike-wave occipital epilepsy in children. Revue d’Electroencéphalographie et de Neurophysiologie Clinique. 1982;12(3):179–201. doi:10.1016/S0370-4475(82)80044-0.

6. Fejerman N. Atypical evolution of benign partial epilepsy in children. Rev Neurol. 1996;24(135):1415–1420.

7. Caraballo RH, Cersósimo RO, Medina CS, et al. Idiopathic partial epilepsy with occipital paroxysms. Rev Neurol. 1997;25(143):1052–1058.

8. Shinnar S, O’Dell C, Berg AT. Distribution of epilepsy syndromes in a cohort of children prospectively monitored from the time of their first unprovoked seizure. Epilepsia. 1999;40(10):1378–1383. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb02008.x.

9. Gaggero R, Pistorio A, Pignatelli S, et al. Early classification of childhood focal idiopathic epilepsies: is it possible at the first seizure? Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2014;18(3):376–380. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2014.01.011.

10. Caraballo RH, Cersósimo RO, Fejerman N. Childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut: a study of 33 patients. Epilepsia. 2008;49(2):288–297. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01322.x.

11. Gastaut H, Pinsard N, Raybaud C, et al. Lissencephaly (agyria-pachygyria): clinical findings and serial EEG studies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1987;29(2):167–180. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1987.tb02132.x.

12. Panayiotopoulos CP, Hallucinations EV. Elementary visual hallucinations, blindness, and headache in idiopathic occipital epilepsy: differentiation from migraine. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66(4):536–540. doi:10.1136/jnnp.66.4.536.

13. Gobbi G, Guerrini R, Grosso S. Late onset childhood occipitalepilepsy (Gastaut type). In: Engel J, Pedley TA, eds. Epilepsy: A ComprehensiveTextbook. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, A Wolters Kluwer Business; 2008:2387–2395.

14. Panayiotopoulos CP, Michael M, Sanders S, Valeta T, et al. Benign childhood focal epilepsies: assessment of established and newly recognized syndromes. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 9):2264–2286. doi:10.1093/brain/awn162.

15. Kuzniecky R, Rosenblatt B. Benign occipital epilepsy: a family study. Epilepsia. 1987;28(4):346–350. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1987.tb03655.x.

16. Nagendran K, Prior PF, Rossiter MA. Benign occipital epilepsy of childhood: a family study. J R Soc Med. 1989;82(11):684–685.

17. Grosso S, Vivarelli R, Gobbi G, et al. Late-onset childhood occipital epilepsy (Gastaut type): a family study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2008;12(5):421–426. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2007.11.007.

18. Taylor I, Berkovic SF, Kivity S, et al. Benign occipital epilepsies of childhood: clinical features and genetics. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 9):2287–2294. doi:10.1093/brain/awn138.

19. Rots ML, de Vos CC, Smeets-Schouten JS, et al. Suppressors of interictal discharges in idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;25(2):189–191.

20. Tsiptsios D, Kokkinos V, Sanders S, et al. Electroencephalographic manifestations and their prognostic significance in idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy of Gastaut. Epilepsia. 2010;51(Suppl 4):156.

21. Kokkinos V, Koutroumanidis M, Tsatsou K, et al. Multifocal spatiotemporal distribution of interictal spikes in Panayiotopoulos syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;121(6):859–869. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2010.01.019.

22. Koutroumanidis M, Tsatsou K, Sanders S, et al. Fixation-off sensitivity in epilepsies other than the idiopathic epilepsies of childhood with occipital paroxysms: a 12-year clinical-video EEG study. Epileptic Disord. 2009;11(1):20–36. doi:10.1684/epd.2009.0235.

23. Fattouch J, Casciato S, Lapenta L, et al. The spectrum of epileptic syndromes with fixation off sensitivity persisting in adult life. Epilepsia. 2013;54:59–65.

24. Beaumanoir A. An EEG contribution to the study of migraine and of the association between migraine and epilepsy in childhood. In: Andermann F, Beaumanoir A, Mira L, et al, eds. Occipital Seizures and Epilepsy in Children. London: John Libbey & Company Ltd; 1993:101–110.

25. Adcock JE, Panayiotopoulos CP. Occipital lobe seizures and epilepsies. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;29(5):397–407. doi:10.1097/WNP.0b013e31826c98fe.

26. Gülgönen S, Demirbilek V, Korkmaz B, et al. Neuropsychological functions in idiopathic occipital lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2000;41(4):405–411. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00181.x.

27. Brancati C, Barba C, Metitieri T, et al. Impaired object identification in idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2012;53(4):686–694. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03410.x.

28. Dalla Bernardina B, Colamaria V, Chiamenti C, et al. Benign partial epilepsy with affective symptoms (“benign psychomotor epilepsy”). In: Roger J, Bureau M, Dravet C, et al, eds. Epileptic Syndromes in Infancy: Childhood and Adolescence. London: John Libby & Company Ltd; 1992:219–223.

29. Beaumanoir A. Infantile epilepsy with occipital focus and good prognosis. Eur Neurol. 1983;22(1):43–52. doi:10.1159/000115535.

30. Martín-Santidrian MA, Garaizar C, Prats-Viñas JM. Frontal lobe epilepsy in infancy: is there a benign partial frontal lobe epilepsy? Rev Neurol. 1998;26(154):919–923.