CHAPTER 85 Selective Peripheral Denervation for Cervical Dystonia

Selective peripheral denervation for the treatment of cervical dystonia (CD) consists mainly of sectioning the peripheral branch of the spinal accessory nerve to the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle, combined with posterior ramisectomy from C1-6.1 The term selective peripheral denervation was coined by Bertrand, who also made the procedure popular in the 1970s.2 Although selective peripheral denervation is a safe procedure with minimal and infrequent side effects and proven efficacy, it is not performed widely because it requires particular expertise with regard to both the phenomenologic differential diagnosis of CD and the surgical techniques.

Cervical Dystonia

CD is the most common form of focal dystonia.3,4 Its prevalence has been estimated to be as high as 13 per 10,000 people in western countries. The mean age of onset is 41 years, and similar to other forms of focal dystonia, there is a female preponderance (about 2.2 : 1). In the vast majority of patients with CD, no underlying cause can be identified. In a few cases, CD is a manifestation of inherited primary dystonia. In some patients, a history of trauma or exposure to neuroleptic drugs is present.

The term cervical dystonia is now preferred and has replaced spasmodic torticollis, for several reasons4,5: few patients present with simple turning of the head; the abnormal movement is not always spasmodic; and, most important, nondystonic neck postures are also referred to as torticollis. CD affects predominantly the neck, including the anterior and posterior muscles. In some patients, the shoulder is involved as well. In approximately one third of patients, CD is one feature of a more widespread segmental dystonia that also involves the facial muscles or upper extremities. CD is characterized by involuntary, patterned, repetitive, and sustained tonic or phasic muscle contractions that result in abnormal movements or postures of the head and neck. Dystonic tremor consists of tremulous or jerking movements of the head that are more irregular than essential tremor. Symptoms are most evident when the patient attempts to move the head contralateral to the force of the dystonia. Most frequently, CD is accompanied by neck pain that may be severe and lead to further incapacitation. In many instances, patients employ a “sensory trick,” such as touching the chin, holding the neck, or other maneuvers, to decrease dystonic activity. Such tricks are also called gestes antagonistique.

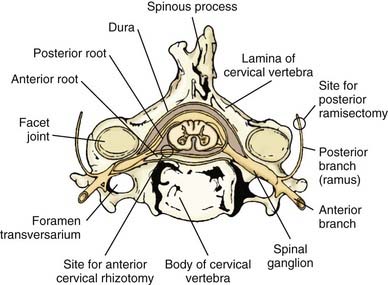

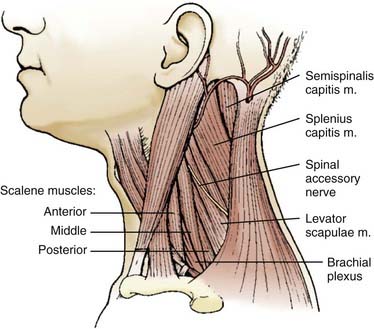

Various basic patterns of CD are defined dependent on the posture of the head.4 Torticollis is defined as rotation of the head about the head-body axis (movement of the chin toward one shoulder in the horizontal plane); laterocollis is defined as a sideward tilt of the head (movement of the ear toward the ipsilateral shoulder); anterocollis is defined as flexion of the neck in the anterior-posterior axis; and retrocollis is defined as extension in the anterior-posterior axis. Lateral shift depicts translation of the axis of the head in the horizontal plane, and sagittal shift in the sagittal plane. Often a combination of these abnormalities is observed, with the pattern determined by the combination of cervical muscles involved (Fig. 85-1). It is important to understand which muscles may be involved based on the patient’s clinical presentation. Even more important when deciding which muscles to denervate is the fact that dystonic activity may vary to produce the individual pattern of dystonia in the same patient.6

FIGURE 85-1 Cervical muscles frequently involved in cervical dystonia.

(Redrawn from Brin MF, Jankovic J, Comella C, et al. Treatment of dystonia using botulinum toxin. In: Kurlan R, ed. Treatment of Movement Disorders. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1995:183-246.)

The differential diagnosis of CD includes a variety of nondystonic disorders.4 Pseudodystonia may be caused by atlantoaxial dislocation, degenerative disk disease, Klippel-Feil syndrome, pediatric posterior fossa tumors, trochlear palsy, Sandifer’s syndrome, and various other disorders. More systemic basal ganglia disorders should be excluded in patients with CD onset at a young age. Long-standing CD may result in enhanced degenerative cervical spine disease followed by cervical myelopathy and radiculopathy.7 Rarely, dystonic postures may lead to fixed deformities secondary to ossification of spinal ligaments or facet joints.8,9

The first-line treatment for CD is chemodenervation with botulinum toxin type A.3,4 The dose and the sites of injection must be individualized to obtain optimal results. The efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin have been demonstrated in several controlled and open-label trials. Most of these report improvement in about 90% of CD patients, with mild side effects in up to 28%.4 The effect of botulinum toxin is usually noted about 1 week after injection, and the average duration of the benefit is 3 to 4 months. In patients who are resistant to botulinum toxin A, botulinum toxin type B may be used, although the average duration of maximal improvement is much shorter and side effects are more frequent than with type A. Pharmacotherapy for CD consists mainly of anticholinergic drugs or muscle relaxants. Overall, medical therapy plays a minor role in the treatment of CD, although many patients benefit from treatment of the chronic pain associated with CD.

Development of Surgery for Cervical Dystonia

Surgical treatment for CD has a long history dating back to ancient Greece.1,5 Myotomies of the SCM were performed as early as 1641, and denervation of cervical muscles was achieved by 1834. Although intradural procedures initially involved sectioning of the posterior cervical roots, attention soon shifted to the anterior roots. McKenzie developed intradural sectioning of both the anterior upper cervical roots and the spinal accessory nerve in the 1920s. Dandy as well as Hamby and Schiffer further refined this procedure,10 which remained the most common surgical procedure for CD until the early 1990s.11,12 Because this “standard” procedure was rather nonselective and resulted in high complication rates, modifications were developed that aimed to denervate the dystonic muscles selectively while preserving normal activity. The results of these efforts were quite variable in terms of both safety and efficacy, but many studies claimed postoperative improvement in 60% to 90% of patients.10–13 It was unclear, however, to what extent the amelioration of abnormal postures or movements translated into improved function, particularly in light of the large number of side effects. A weak or unstable neck was estimated to occur in up to 40% of patients after bilateral rhizotomy.11 Transient dysphagia was noted in up to 30%. Better results with fewer side effects were seen with selective approaches targeting only those nerves supplying clearly dystonic muscles and with staging of the procedure.14

Microvascular decompression of the spinal accessory nerve has been attempted, based on the hypothesis that CD is analogous to vascular compressive disorders such as hemifacial spasm and trigeminal neuralgia. Pathophysiologic concepts do not support microvascular decompression as a valid treatment option for CD, however, and the outcome data are ambiguous; therefore, microvascular decompression cannot be recommended for the treatment of CD at this time.1,15 Similarly, cervical spinal cord stimulation for CD has been abandoned.16,17

Selective peripheral denervation, including posterior ramisectomy and spinal accessory nerve sectioning, was pioneered by Bertrand in the 1970s.2,18 Bertrand clearly demonstrated that this innovative operation was much more selective than the intradural procedures used in the past and entailed less risk. One of the main advantages of selective peripheral denervation is that it is a completely extraspinal, extradural procedure (Fig. 85-2). Further, the approach can be applied from C1-6 and can be performed unilaterally or bilaterally in one session. Over the past two decades, selective ramisectomy and peripheral denervation, sometimes combined with myotomy, have largely replaced intradural rhizotomy as the ablative procedure of choice for CD.19–26 Given its less favorable risk-benefit profile, intradural rhizotomy can no longer be recommended.15

Indications and Patient Selection for Selective Peripheral Denervation

Selective peripheral denervation is indicated in patients with CD who do not respond adequately to medical therapy and repeated botulinum toxin injections. It is estimated that 6% to 14% of patients with CD are primary nonresponders to botulinum toxin injections,3,4 and another 3% to 10% develop immunoresistance over time. In general, patients with predominantly tonic dystonia are better candidates for selective peripheral denervation than those with prominent phasic movements.1 Patients with marked myoclonus or dystonic head tremor are poor candidates for the procedure. In some patients selective peripheral denervation may serve as an adjunct or also as an alternative to continued botulinum toxin therapy.

It is crucial to tailor the denervation procedure to each patient’s symptoms. This may involve several successive operative steps as well as augmentative myotomy or myectomy.14,27 The primary goal is to selectively weaken the dystonic muscles while preserving normal muscle function, thereby avoiding side effects. The patient and the treating neurologist should be informed that staged procedures may be necessary to achieve an optimal result. The muscles with the most prominent dystonic activity are usually identified on clinical grounds by observing the pattern of the patient’s dystonia and directly palpating the neck muscles. Electromyography may be useful in some cases.28 In addition to the muscles usually involved in CD (SCM, trapezius, splenius, semispinalis), other muscles such as the levator scapulae, scalene, longus colli, and paraspinal erector trunci should be investigated.

There are several rating scales available to quantify the severity of both the movement disorder and the disease-specific disability in patients with CD.4 The most widely used is the Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale and its modifications. Subscales include measures of dystonia severity, pain, and disability. Another specific scale for CD is the Tsui Scale. Subscores of the Burke-Fahn-Marsden Dystonia Scale, Unified Dystonia Rating Score, and Global Dystonia Rating Scale are used as well. We also recommend standard videotaping of patients preoperatively.

Surgical Technique

Patients are operated on under general anesthesia. There have been several modifications of Bertrand’s original technique.21–2325 Both the posterior ramisectomy and the SCM denervation can be performed in one draping when the patient is positioned semisitting with the head fixed in a Mayfield head holder. However, because of the danger of air embolism,25 and because the only advantage of the semisitting position is the possibility of completing both procedures through one approach, most neurosurgeons prefer to perform the ramisectomy with the patient in the prone position and then the SCM denervation with the patient in the supine position.

Posterior Ramisectomy

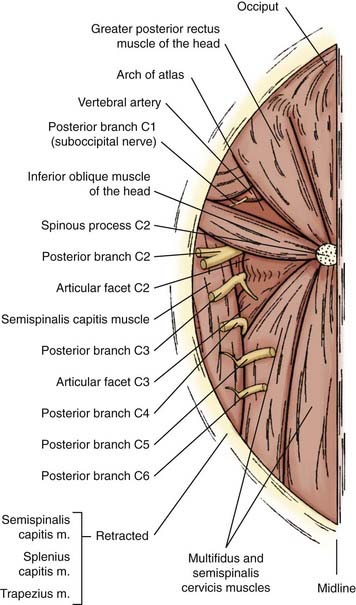

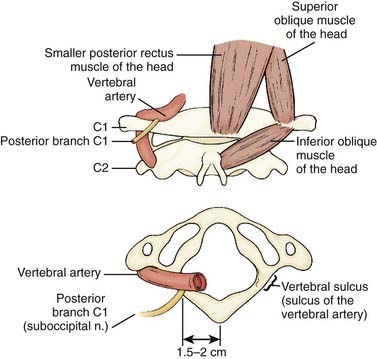

Denervation of the posterior rami to the neck muscles is performed via a midline incision in the plane of the ligamentum nuchae extending from the posterior rim of the foramen magnum to the spinous process of C6. The posterior neck muscles are mobilized laterally by subperiosteal dissection. A useful alternative is the technical variant described by Braun and Richter, in which the cleavage plane between the more superficially located semispinalis capitis muscle and the more deeply located semispinalis cervicis and multifidus muscles is dissected20,21 (Fig. 85-3). The inferior oblique capitis muscle is detached from its origin at the spinous process of C2. The dissection then proceeds farther laterally to the articular facets. The posterior rami are identified in the cleavage plane that has been created, at the point where they emerge lateral to the facet joints. With the help of the surgical microscope and bipolar stimulation, the small posterior branches from C3-6 are identified. Bipolar stimulation at this point may evoke strong muscle contractions of the posterior neck muscles. After the main branches have been identified, they are sectioned and resected. It is also important to identify smaller nerve branches to the multifidus, splenius, and semispinalis muscles. The C3 and C4 posterior rami are usually identified easily; however, the C5 and C6 rami may be more difficult to find. The C2 ganglion is located just above the arch of the axis. It is embedded in a rich venous plexus that requires hemostasis with bipolar coagulation, Surgicel, and sometimes wax. Once the C2 ganglion has been identified, both the ventral and dorsal rami and the distal portions of the anterior and posterior nerve roots can all be identified extradurally. At this point, either sectioning of the greater occipital nerve or a C2 ganglionectomy can be performed. The latter is my preferred method. Because the greater occipital nerve is formed by the posterior C2 ramus, most patients experience hypesthesia in the distribution of this nerve, which generally causes little discomfort. The most difficult branch to find is the posterior branch of C1, the suboccipital nerve (Fig. 85-4). It is located between the arch of the atlas and the vertebral artery in the sulcus of the vertebral artery, where bleeding may occur from the surrounding venous plexus. Finally, bipolar stimulation is used to identify any remaining tiny nerve branches, which are sectioned and resected. Myotomies and partial myectomies may be added. If required, ramisectomy can be performed on both sides during the same operative session. A drain is placed before the wound is closed.

Myotomy and Partial Myectomy

At present, myotomies and myectomies are employed predominantly as adjuncts to selective peripheral denervation.27 Among early case series of myotomy without denervation, long-term benefits were generated only when extensive myectomies were performed.13,29–31 Myotomies and myectomies are useful when dystonic activity spreads beyond the posterior neck muscles and the SCM. Myotomies and partial myectomies are indicated particularly if there is pronounced dystonic activity in the scalene, levator scapulae, and omohyoid muscles, as well as in the trapezius muscle. Denervation of the trapezius muscle is not advised because this would render the patient unable to elevate the arm above the horizontal plane. An asleep-awake-asleep operative technique for selective partial myectomy of the trapezius muscle has been described.27

Variants and Special Indications

As indicated earlier, several technical variants have been devised for selective peripheral denervation and myotomy. One variant is the technique of Taira, who combines an intradural anterior rhizotomy of C1 and C2 with standard posterior ramisectomy of the lower segments.32,33

The levator scapulae muscle, which is frequently involved in laterocollis, may be denervated selectively as an addition to posterior ramisectomy.19,34

Although the primary goal of selective peripheral denervation is to improve the patient’s dystonic head position, it may also be used in patients with a fixed skeletal deformity due to long-standing CD.8,9 There will be no change in the head position, but these patients may benefit from reduced pain secondary to a reduction in the dystonic muscular activity.

Clinical Outcomes

Several studies have shown the efficacy of peripheral selective denervation for CD since its inception in the 1970s.2,14,18,20–26,33,35,36 However, the proportion of patients who benefit and the degree of improvement vary greatly among series. One of the factors contributing to this variability is the instrument by which outcome is measured. Nevertheless, selective peripheral denervation has been demonstrated to have a favorably low risk-benefit ratio.

Both clinical improvement and reduced disability have been reported in 70% to 90% of patients in most series. The degree of improvement, however, has shown greater variation. Braun and Richter20,22 reported that in 112 consecutive patients undergoing operation, 14% had complete relief of symptoms, 33% had marked improvement, 24% had moderate improvement, and 31% had minimal or no improvement. In this series, outcome was closely correlated with the response to botulinum toxin injections before surgery. In summary, 83% of patients who were secondary nonresponders to botulinum toxin injections had satisfying outcomes after surgery, whereas only 50% of primary nonresponders considered their postoperative results beneficial. Cohen-Gadol and colleagues23 reported that 70% of their 130 patients achieved moderate to excellent amelioration of head position and pain at a mean of 3.5 years after selective peripheral denervation. In a smaller study by Ford and colleagues,24 the benefit was less robust at a mean of 5 years’ follow-up; lasting improvement was reported in approximately one third of patients, with an average 30% reduction in dystonia. An interesting observation was made by Chawda and associates,7 who noted that CD patients with more signs of degenerative cervical spondylosis had less beneficial responses to selective denervation than did patients without such changes.

Complications from selective peripheral denervation are rare. Denervation of C2 invariably causes numbness in the territory of the greater occipital nerve in the early postoperative period, but this is almost always well tolerated. Patients should be informed about this procedure-related numbness when informed consent is obtained. Neuropathic pain has been reported only in rare circumstances.36 Some studies have reported swallowing difficulties, but these did not add to disability.37 One percent to 2% of patients may experience weakness in nondystonic muscles, particularly in the trapezius when the trapezius branch of the spinal accessory nerve is injured.21 Rarely, patients experience prolonged localized pain after myectomy. No instances of head or neck instability have been reported.

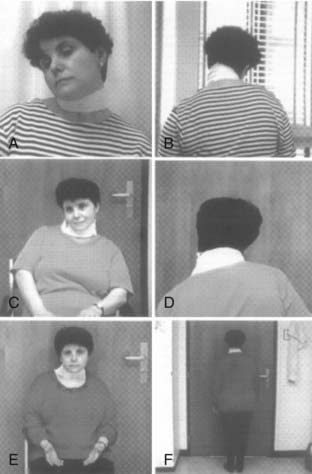

Previously, my colleagues and I demonstrated that the benefit of selective denervation procedures for CD correlates with the number of operative procedures performed in an individual patient.14 Therefore, if the clinical outcome following the first denervation procedure is less than expected, a second or sometimes even a third procedure should be considered (Fig. 85-5). Such an approach lessens the risk of dysphagia, which may occur when extensive denervation procedures are performed in one surgical session. Further, staged denervation procedures take into account that reinnervation can occur and that a particular head position may be generated by the activity of different muscles at different times.6

In August 2004, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence in the United Kingdom provided guidelines for selective peripheral denervation in CD.36 In addition, a systematic review was provided by a European Federation of Neurological Societies task force.15 According to these reports, selective peripheral denervation is recommended as a safe procedure with infrequent and minimal side effects that is indicated exclusively in CD (level C).15,36

Future Strategies

A variety of surgical treatments for CD are now available.1 Compared with intradural procedures and rhizotomies, peripheral denervation and posterior ramisectomy are less invasive and yield greater postoperative benefits with lower complication rates. Nevertheless, selective peripheral denervation is not suitable for all CD patients. For those patients who are unwilling or unable to undergo selective denervation, bilateral pallidal deep brain stimulation (DBS) may be appropriate.38 Initially, DBS was reserved for patients with “complex” CD (marked translation of the head in the sagittal or lateral axis in relation to the trunk, prominent retrocollis or anterocollis, or continuous phasic dystonic movements and dystonic head tremor). Over the past 10 years, bilateral pallidal DBS has become an accepted treatment for CD and is now used even in less complex cases.39 Overall, the benefit after bilateral pallidal DBS may be somewhat better than after selective peripheral denervation. Most studies have shown improvements of approximately 60% on the Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale for movement, disability, and pain; the improvements appear to be stable on long-term follow-up (up to 8 years).29 In experienced hands, complications of DBS are rare. At present, pallidal DBS is considered a second-line treatment in patients with medically refractory generalized dystonia; however, this is not the case in those with CD because other surgical options, such as peripheral denervation, are available.15 Nevertheless, we can expect to see an increase in the use of pallidal DBS for the treatment of CD in the future.

Bertrand CM. Selective peripheral denervation for spasmodic torticollis: surgical technique, results, and observations in 260 cases. Surg Neurol. 1993;40:96-103.

Braun V, Richter HP. Selective peripheral denervation for spasmodic torticollis: 13-year-experience with 155 patients. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(Suppl 2):207-212.

Braun V, Richter HP. Selective peripheral denervation for the treatment of spasmodic torticollis. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:58-62.

Chen X. Selective resection and denervation of cervical muscles in the treatment of spasmodic torticollis: results in 60 cases. Neurosurgery. 1981;8:680-688.

Cohen-Gadol AA, Ahlskog JE, Matsumoto JY, et al. Selective peripheral denervation for the treatment of intractable spasmodic torticollis: experience with 168 patients at the Mayo Clinic. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:1247-1254.

Ford B, Louis ED, Greene P, Fahn S. Outcome of selective ramisectomy for botulinum toxin resistant torticollis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:472-478.

Friedman AH, Nashold BSJr, Sharp R, et al. Treatment of spasmodic torticollis with intradural selective rhizotomies. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:46-53.

Girard F, Ruel M, McKenty S, et al. Incidences of venous air embolism and patent foramen ovale among patients undergoing selective peripheral denervation in the sitting position. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:316-319.

Hamby WB, Schiffer S. Spasmodic torticollis: results after cervical rhizotomy in 80 cases. Clin Neurosurg. 1970;17:28-37.

Hernesniemi J, Keränen T. Long-term outcome after surgery for spasmodic torticollis. Acta Neurochir. 1990;103:128-130.

Krauss JK. Deep brain stimulation for treatment of cervical dystonia. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97:201-205.

Krauss JK, Toups EG, Jankovic J, Grossman RG. Symptomatic and functional outcome of surgical treatment of cervical dystonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63:642-648.

Münchau A, Filipovic SR, Oester-Barkey A, et al. Spontaneously changing muscular activation pattern in patients with cervical dystonia. Mov Disord. 2001;16:1091-1097.

Münchau A, Good CD, McGowan S, et al. Prospective study of swallowing function in patients with cervical dystonia undergoing selective peripheral denervation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:67-72.

Münchau A, Palmer JD, Dressler D, et al. Prospective study of selective peripheral denervation for botulinum-toxin resistant patients with cervical dystonia. Brain. 2001;124:769-783.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Selective peripheral denervation of cervical dystonia. www.nice.org.uk, 2004.

Taira T, Hori T. A novel denervation procedure for idiopathic cervical dystonia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2003;80:92-95.

Taira T, Kobayashi T, Hori T. Selective peripheral denervation of the levator scapulae muscle for laterocollic cervical dystonia. J Clin Neurosci. 2003;10:449-452.

Weigel R, Capelle HH, Krauss JK. Cervical dystonia in Bechterev disease resulting in atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation and craniocervical osseous fusion. Spine. 2007;32:E781-E784.

1 Krauss JK, Loher TJ. Surgery for dystonia. In: Warner TT, Bressman S, editors. Clinical Diagnosis and Management of Dystonia. London: Informa Healthcare; 2007:209-222.

2 Bertrand CM. Selective peripheral denervation for spasmodic torticollis: surgical technique, results, and observations in 260 cases. Surg Neurol. 1993;40:96-103.

3 Brin MF, Jankovic J, Comella C, et al. Treatment of dystonia using botulinum toxin. In: Kurlan R, editor. Treatment of Movement Disorders. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1995:183-246.

4 Jankovic J. Treatment of cervical dystonia. In: Brin MF, Comella CL, Jankovic J, editors. Dystonia: Etiology, Clinical Features, and Treatment. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:159-166.

5 Krauss JK, Grossmann RG, Jankovic J. Treatment options for surgery of cervical dystonia. In: Krauss JK, Jankovic J, Grossmann RG, editors. Surgery for Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:323-334.

6 Münchau A, Filipovic SR, Oester-Barkey A, et al. Spontaneously changing muscular activation pattern in patients with cervical dystonia. Mov Disord. 2001;16:1091-1097.

7 Chawda SJ, Münchau A, Johnson D, et al. Pattern of premature degenerative changes of the cervical spine in patients with spasmodic torticollis and the impact on the outcome of selective peripheral denervation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:465-471.

8 Weigel R, Rittmann M, Krauss JK. Spontaneus craniocervical osseous fusion resulting from cervical dystonia. J Neurosurg (Spine). 2001;95:115-118.

9 Weigel R, Capelle HH, Krauss JK. Cervical dystonia in Bechterev disease resulting in atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation and craniocervical osseous fusion. Spine. 2007;32:E781-E784.

10 Hamby WB, Schiffer S. Spasmodic torticollis: results after cervical rhizotomy in 80 cases. Clin Neurosurg. 1970;17:28-37.

11 Colbassani HJJr, Wood JH. Management of spasmodic torticollis. Surg Neurol. 1986;25:153-158.

12 Friedman AH, Nashold BSJr, Sharp R, et al. Treatment of spasmodic torticollis with intradural selective rhizotomies. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:46-53.

13 Hernesniemi J, Keränen T. Long-term outcome after surgery for spasmodic torticollis. Acta Neurochir. 1990;103:128-130.

14 Krauss JK, Toups EG, Jankovic J, Grossman RG. Symptomatic and functional outcome of surgical treatment of cervical dystonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63:642-648.

15 Albanese A, Barnes MP, Bhatia KP, et al. A systematic review on the diagnosis and treatment of primary (idiopathic) dystonia and dystonia plus syndromes: report of an EFNS/MDS-ES Task Force. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:433-444.

16 Fahn S. Lack of benefit from cervical cord stimulation for dystonia. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1229.

17 Gildenberg PL. Treatment of spasmodic torticollis by dorsal column stimulation. Appl Neurophysiol. 1978;41:113-121.

18 Bertrand CM. Surgical management of spasmodic torticollis and adult-onset dystonia. In: Schmidek HH, Sweet WH, editors. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995:1649-1659.

19 Anderson WS, Lawson HC, Belzberg AJ, Lenz FA. Selective denervation of the levator scapulae muscle: an amendment to the Bertrand procedure for the treatment of spasmodic torticollis. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:757-763.

20 Braun V, Richter HP. Selective peripheral denervation for the treatment of spasmodic torticollis. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:58-62.

21 Braun V, Richter HP. Selective peripheral denervation and posterior ramisectomy in cervical dystonia. In: Krauss JK, Jankovic J, Grossmann RG, editors. Surgery for Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:335-342.

22 Braun V, Richter HP. Selective peripheral denervation for spasmodic torticollis: 13-year-experience with 155 patients. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(Suppl 2):207-212.

23 Cohen-Gadol AA, Ahlskog JE, Matsumoto JY, et al. Selective peripheral denervation for the treatment of intractable spasmodic torticollis: experience with 168 patients at the Mayo Clinic. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:1247-1254.

24 Ford B, Louis ED, Greene P, Fahn S. Outcome of selective ramisectomy for botulinum toxin resistant torticollis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:472-478.

25 Girard F, Ruel M, McKenty S, et al. Incidences of venous air embolism and patent foramen ovale among patients undergoing selective peripheral denervation in the sitting position. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:316-319.

26 Münchau A, Palmer JD, Dressler D, et al. Prospective study of selective peripheral denervation for botulinum-toxin resistant patients with cervical dystonia. Brain. 2001;124:769-783.

27 Krauss JK, Koller R, Burgunder JM. Partial myotomy/myectomy of the trapezius muscle with an asleep-awake-asleep anesthetic technique for treatment of cervical dystonia. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:889-891.

28 Münchau A, Bahlke G, Allen PJ, et al. Polymyography combined with time-locked video recording (video EMG) for presurgical assessment of patients with cervical dystonia. Eur Neurol. 2001;45:222-228.

29 Chen X. Selective resection and denervation of cervical muscles in the treatment of spasmodic torticollis: results in 60 cases. Neurosurgery. 1981;8:680-688.

30 Chen X, Ji SX, Zhu H, et al. Operative treatment of bilateral retrocollis. Acta Neurochir. 1991;113:180-183.

31 Chen X, Ma A, Liang J, et al. Selective denervation and resection of cervical muscles in the treatment of spasmodic torticollis: long-term follow-up results in 207 cases. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2000;75:96-102.

32 Taira T, Hori T. A novel denervation procedure for idiopathic cervical dystonia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2003;80:92-95.

33 Taira T, Kobayashi T, Takahashi K, Hori T. A new denervation procedure for idiopathic cervical dystonia. J Neurosurg.. 2002;97(2 Suppl):201-206.

34 Taira T, Kobayashi T, Hori T. Selective peripheral denervation of the levator scapulae muscle for laterocollic cervical dystonia. J Clin Neurosci. 2003;10:449-452.

35 Meyer CHA. Outcome of selective peripheral denervation for cervical dystonia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2001;77:44-47.

36 National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Selective peripheral denervation of cervical dystonia. www.nice.org.uk, 2004.

37 Münchau A, Good CD, McGowan S, et al. Prospective study of swallowing function in patients with cervical dystonia undergoing selective peripheral denervation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:67-72.

38 Krauss JK, Pohle T, Weber S, et al. Bilateral stimulation of globus pallidus internus for treatment of cervical dystonia. Lancet. 1999;354:837-838.

39 Krauss JK. Deep brain stimulation for treatment of cervical dystonia. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97:201-205.