Chapter 292 Schistosomiasis (Schistosoma)

Etiology

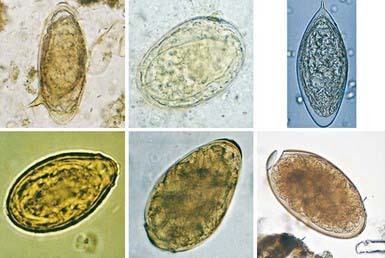

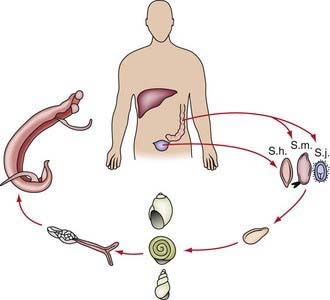

Schistosoma organisms are the trematodes, or flukes, that parasitize the bloodstream. Five schistosome species infect humans: Schistosoma haematobium, S. mansoni, S. japonicum, S. intercalatum, and S. mekongi. Humans are infected through contact with water contaminated with cercariae, the free-living infective stage of the parasite. These motile, forked-tail organisms emerge from infected snails and are capable of penetrating intact human skin. As they reach maturity, adult worms migrate to specific anatomic sites characteristic of each schistosome species: S. haematobium adults are found in the perivesical and periureteral venous plexus, S. mansoni in the inferior mesenteric veins, and S. japonicum in the superior mesenteric veins. S. intercalatum and S. mekongi are usually found in the mesenteric vessels. Adult schistosome worms (1-2 cm long) are clearly adapted for an intravascular existence. The female accompanies the male in a groove formed by the lateral edges of its body. On fertilization, female worms begin oviposition in the small venous tributaries. The eggs of the 3 main schistosome species have characteristic morphologic features: S. haematobium has a terminal spine, S. mansoni has a lateral spine, and S. japonicum has a smaller size with a short, curved spine (Fig. 292-1). Parasite eggs provoke significant granulomatous inflammatory response, which allows them to ulcerate through host tissues to reach the lumen of the urinary tract or intestines. They are carried to the outside environment in urine or feces, where they will hatch if deposited in freshwater. Motile miracidia emerge, infect specific freshwater snail intermediate hosts, and divide asexually. After 4-12 wk, the infective cercariae are released by the snails into the contaminated water.

Epidemiology

Transmission depends on disposal of excreta, the presence of specific intermediate snail hosts, and the patterns of water contact and social habits of the population (Fig. 292-2). The distribution of infection in endemic areas shows that prevalence increases with age to a peak at 10-20 yr of age. Measuring intensity of infection (by quantitative egg count in urine or feces) demonstrates that the heaviest worm loads are found in the younger age groups. Therefore, schistosomiasis is most prevalent and most severe in children and young adults, who are at maximal risk for suffering from its acute and chronic sequelae.

Carod-Artal FJ. Neurological complications of Schistosoma infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:107-116.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Schistosomiasis (website). www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/schistosomiasis/default.htm. Accessed September 7, 2010

Coutinho HM, Acosta LP, Wu HW, et al. Th2 cytokines are associated with persistent hepatic fibrosis in human Schistosoma japonicum infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:288-295.

Dawson-Hahn EE, Greenberg SLM, Domachowske JB, et al. Eosinophilia and the seroprevalence of schistosomiasis and strongyloidiasis on newly arrived pediatric refugees: an examination of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention screening guideline. J Pediatr. 2010;156:1016-1018.

Dent A, King CH. Schistosomiasis section in Epocrates Online Reference Program. https://online.epocrates.com/home. posted September 29, 2008

Doenhoff MJ, Cioli D, Utzinger J. Praziquantel: mechanisms of action, resistance and new derivatives for schistosomiasis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:659-667.

2007 Drugs for parasitic infections. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2007;5(suppl):e1-e15.

King CH, Dickman K, Tisch DJ. Reassessment of the cost of chronic helminth infection: meta-analysis of disability-related outcomes in endemic schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2005;365:1561-1569.

Leenstra T, Coutinho HM, Acosta LP, et al. Schistosoma japonicum reinfection after praziquantel treatment causes anemia associated with inflammation. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6398-6407.

Ross AG, Vickers D, Olds GR, et al. Katayama syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:218-224.

Wang L, Utzinger J, Zhou XN. Schistosomiasis control: experiences and lessons from China. Lancet. 2008;372:1793-1794.

Wang LD, Chen HG, Guo JG, et al. A strategy to control transmission of Schistosoma japonicum in China. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:121-128.