Chapter 78 Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology characterized by intrathoracic involvement. The disease was first described as early as 1869, but its protean presentation and clinical course still make sarcoidosis a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for modern-day physicians. Ocular involvement is common and has been previously reported to occur in approximately 15–25% of patients with sarcoidosis.1,2 However, some series have reported higher rates. Posterior-segment manifestations may account for up to 28% of the lesions seen in patients with ocular sarcoid. Most large case series of patients with uveitis report that approximately 5% of patients with uveitis have biopsy-confirmed systemic sarcoidosis.3–6

General considerations

Epidemiology

Sarcoidosis is worldwide in its distribution, but it is most frequently recognized in developed countries where adequate diagnostic facilities are available. Although all races are affected, series in the USA generally show that the disease is more prevalent in blacks than in whites. It has also been noted that the prevalence of sarcoidosis in black populations of Africa and South America is less than what has been observed in the African American population.7–9 Both sexes are affected, with the overall frequency showing a very slight excess of females (approximately 60%). Sarcoidosis is a disease of young adults, with almost three-fourths of cases occurring in those younger than 40 years of age. Children may be affected, but this is uncommon.6–10 The clinical course of childhood sarcoidosis is often atypical; that is, there is less frequent pulmonary involvement and more frequent extrathoracic disease.11,12 A recent study of 46 caucasian children from Denmark reported the four most frequent presenting symptoms to be erythema nodosum (22%), iridocyclitis (22%), peripheral lymphadenopathy (15%), and cutaneous sarcoidosis (7%). Overall, a good prognosis was observed. Moreover, erythema nodosum was generally associated with good outcomes while central nervous system (CNS) involvement was associated with a poor prognosis.13 These children must be differentiated from children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and those with familial juvenile systemic granulomatosis14–17 because of the similarity of ocular and articular involvement. Many cases of familial juvenile systemic granulomatosis are misdiagnosed as childhood sarcoidosis.18

Etiology and pathogenesis

The etiology of sarcoidosis is unknown. Multiple etiologies have been proposed, including a variety of infectious agents, allergy to pine pollen and peanut dust, chewing pine pitch, and hypersensitivity to chemicals such as beryllium or zirconium. To date, there is no conclusive evidence to implicate any of these as an etiologic agent. Familial studies and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing have suggested a possible genetic predisposition, but these studies are far from conclusive.19 A cooperative multicenter study, A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis (ACCESS), enrolled 736 biopsy-confirmed cases from 10 centers in the USA and suggested a genetic predisposition for sarcoidosis, presenting evidence for the allelic variation at the HLA-DRB1 locus as a contributing factor to the disease. The most significant finding was the relationship between DRB1*0401 and eye involvement (P ≤ 0.0008; odds ratio (OR) 3.49) in the study population. Although only 2% of blacks had a DRB1*0401 allele, a similar OR was present in both blacks and whites.19

Bronchoalveolar lavage has enabled investigators to determine the immunologic events at the area of active disease in the lungs. These studies have shown entirely different results from peripheral blood lymphocytes. In the lungs, there is an excess of helper T lymphocytes (CD4+). These activated helper T cells spontaneously secrete lymphokines, including interleukin-2 (IL-2), and will polyclonally activate B cells to produce immunoglobulins. These studies have been interpreted to show that an active T-cell-driven immunologic response occurs at the target organ site and eventually leads to granuloma formation.21,22 Studies of bronchoalveolar lavage fluids have suggested that macrophages may also play a role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary sarcoidosis by inducing changes in the pulmonary microvasculature.23

Immunohistologic studies of biopsy tissue from patients with sarcoidosis have demonstrated the presence of cells of macrophage lineage and activated T cells in the granuloma. The vast majority of lymphocytes are T cells of the helper subset (CD4+) and express activation markers, including class II antigens and the IL-2 receptor.24–26

Clinical features

The organs most frequently involved in sarcoidosis are the lungs, lymph nodes and spleen, skin, eyes, nervous system, and bones and joints1,19,27–29 (Table 78.1).

| Organ system | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Intrathoracic | 84–93 |

| Hilar nodes | 60–77 |

| Lung parenchyma | 40–56 |

| Lymph nodes | 23–37 |

| Eyes | 11–32 |

| Skin | 12–27 |

| Erythema nodosum | 4–31 |

| Spleen | 1–18 |

| Bones | 2–9 |

| Parotid | 5–8 |

| Central nervous system | 2–7 |

Intrathoracic sarcoidosis

Several series have demonstrated that intrathoracic involvement is the most common manifestation of sarcoidosis and occurs in 90% of patients. An abnormality on chest radiograph examination is evident at the onset of sarcoidosis in almost all patients. Chest radiograph abnormalities have been classified according to a simple staging system, which closely correlates with the eventual outcome. Stage 0 is characterized by a normal chest radiograph; stage 1 is characterized by bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy without pulmonary infiltration and is seen in 65% of patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis; stage 2 is characterized by hilar lymphadenopathy associated with pulmonary infiltration and is seen in 22% of patients with sarcoid; stage 3 sarcoid is characterized by pulmonary infiltration with fibrosis but without bilateral hilar adenopathy and occurs in 13% of patients. The overall rates of radiographic resolution are 59%, 39%, and 38% for stage 1, 2, and 3 disease, respectively.1

Extrapulmonary lesions

Involvement of the reticuloendothelial system, particularly the extrapulmonary lymph nodes or spleen, or both, is common and occurs in 23–37% of patients with sarcoidosis. Biopsy of a palpable lymph node is often used for histologic confirmation of the diagnosis of sarcoidosis (see below). Skin lesions occur frequently in sarcoidosis and include erythema nodosum, lupus pernio, maculopapular rashes, cutaneous plaques, and subcutaneous nodules. Lupus pernio (dusky-purple infiltration of the skin of the nose) and sarcoid plaques are typically associated with chronic disease, whereas erythema nodosum (especially in the presence of polyarthritis) is typically associated with acute sarcoid or Lofgren syndrome.30 Neurosarcoidosis occurs in 2–7% of patients with sarcoid. Facial palsy is the most frequent manifestation of neurosarcoidosis. Other presentations include other cranial nerve palsies, papilledema, peripheral neuropathy, meningitis, space-occupying cerebral lesions, cavernous sinus syndrome,31 and endocrine disorders such as hypopituitarism or diabetes insipidus resulting from space-occupying lesions. Musculoskeletal involvement includes bone cysts in patients with chronic sarcoid, polyarthralgias, and periarthritis in patients with acute sarcoid, and, less commonly, myopathy from granulomatous lesions within muscles.1,19,29,31–35

Investigations

Radiological evaluation

High-resolution computed tomography (CT)

The CT findings in sarcoidosis can be divided into three main categories:

The presence of diffuse nodular opacities (1–5 mm) with irregular borders in the perilymphatic distribution typically in the upper and middle lung zones is the most common and almost universal finding in the lung parenchyma.36 The presence of architectural distortion is also exclusive to sarcoidosis as opposed to other diseases with perilymphatic distribution.37 “Sarcoid galaxy sign,” which is a collection of multiple granulomas and gives the impression of an opacity, is present in 10–20% of patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis.38 Extensive fibrosis, mostly distributed in the upper and middle zones associated with architectural distortion, is also seen in 20–25% of cases. The presence of air trapping at end expiration has been reported frequently. Terasaki et al.39 reported air trapping on expiration in 45 (98%) of their study patients. Devies et al.40 demonstrated that the extent of air trapping on expiration was correlated with the pulmonary function of the patient.

Large-airway involvement is seen in 1–3% of patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. This typically presents with tracheal stenosis due to granuloma formation within the tracheal mucosa or submucosa or secondary to lymph node compression from the outside. More than 60% of patients with sarcoidosis are reported to have smooth thickening of the smaller airways.36

The classic radiologic finding in the mediastinum of a sarcoid patient is symmetric bilateral hilar adenopathy with some form of paratracheal adenopathy. Symmetry is an important diagnostic feature of the sarcoid hilar adenopathy as it is uncommon in the major diagnostic alternatives, including tuberculosis and lymphoma.36

Gallium scan

Gallium-67 is a radioactive isotope with a half-life of 78 hours and is administered intravenously to patients as Ga-citrate. In the vascular system, the half-life of Ga drops to 12 hours. Ga is taken up by activated macrophages in the epithelioid cell granulomas. Such uptake is detected by gamma cameras 48 hours after injection and is assessed in the liver, spleen, thorax, eyes, and lacrimal and salivary glands. Scanning has also been suggested as a useful diagnostic test for sarcoidosis. The test is again nonspecific, and gallium uptake is seen in other diseases, including Sjögren syndrome, tuberculosis, radiation therapy, and lymphoma. It has been proposed that the combination of gallium scanning and an elevated angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level is highly specific for sarcoidosis, but these studies have employed patients specifically chosen for very active sarcoid.41 As such, these tests may be of less utility in a patient with presumed sarcoid uveitis and no obvious evidence of systemic sarcoidosis. The best use of these tests may be in following patients with active disease.42,43

In a study of 22 patients with sarcoid uveitis compared to 70 patients with uveitis secondary to other disorders, Power et al.44 reported that the sensitivity and specificity of an elevated ACE alone in diagnosing sarcoidosis were 73% and 83%, respectively, and that the sensitivity and specificity of the gallium scan alone were 91% and 84%, respectively. Using the combination of a gallium scan and an elevated serum ACE, the specificity for diagnosing sarcoidosis was 100% and the sensitivity was 73%. The authors concluded that the combination of serum ACE level and whole-body gallium scan might be useful for diagnosing sarcoidosis in patients with uveitis. However, because of the study design inherent in investigating the values of these tests, their actual utility in patients with normal chest radiographs and without clinical evidence of sarcoid remains uncertain. Furthermore, because the reported prevalence of sarcoid uveitis is approximately 5% among patients with biopsy-confirmed systemic sarcoidosis,3–6 routine screening of all patients with uveitis by both ACE levels and gallium scan may have a low positive predictive value and, therefore, may be misleading. Nevertheless, in selected patients in whom sarcoidosis is highly likely, these tests may be useful.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positive emission tomography scan (PET)

Fluorodeoxyglucose PET (18F-FDG PET) scanning has become of great importance in the study and follow-up of patients with cancer. However, in recent years, its role in the diagnosis and management of other conditions such as sarcoidosis has been explored. Although the sensitivity of a whole-body PET scan to detect sarcoid lesions is 80–100%, the findings are nonspecific and histology is required to confirm or rule out sarcoidosis. MRI has been successfully used in the evaluation of organ-specific damage in patients with sarcoidosis, especially cardiac and musculoskeletal tissue.41,44–48

Histology

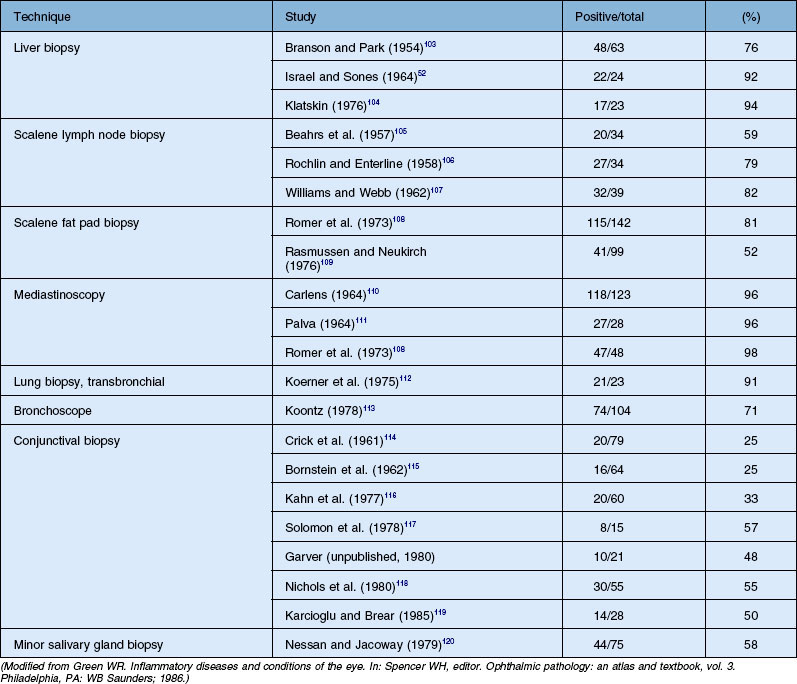

Histologic confirmation (Table 78.2) is generally required to establish the diagnosis of sarcoid. The only clinical situation when diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be strongly considered reliably without biopsy is Löfgren syndrome (see below). Otherwise, biopsy should be done. Sites most often biopsied include the lungs, mediastinal lymph nodes, skin, peripheral lymph nodes, liver, and conjunctiva. Biopsy of clinically evident skin lesions or palpable lymph nodes is frequently performed because of the high yield and low morbidity. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy with transbronchial lung biopsy is positive in 80% of patients with intrapulmonary sarcoidosis. This procedure is routinely performed by pulmonary physicians and has a relatively low morbidity. The next step in such a scenario is cervical mediastinoscopy, which is both highly invasive and an expensive procedure. The requirement of general anesthesia further increases the chances of complications from the procedure. From the patient’s perspective it is important that further possibilities of minimally invasive techniques for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis are explored. Development of linear echoendoscopes and subsequent procedures (endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) and endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) ) has opened new diagnostic possibilities for sarcoidosis. Both techniques allow real-time monitoring of the needle. Several investigators have reported a high sensitivity of 72–85% for EBUS-TBNA and minimal complications. In a randomized control trial (RCT) Tremblay et al.49 have shown that the diagnostic yield of EBUS-guided TBNA (95.8%) versus the conventional TBNA (73.1%) was 22.7% greater. Sensitivity and specificity were 60.9% and 100%, respectively, in the standard TBNA group, and 83.3% and 100%, respectively, in the EBUS-guided TBNA group (absolute increase in sensitivity of 22.5%). EUS-FNA was used for diagnosis of sarcoidosis and had a yield of 82% and sensitivity of 89–94% by assessing noncaseating granulomas in mediastinal nodes.50 The liver biopsy is often positive in patients with sarcoidosis, but the finding of granulomatous lesions on liver biopsy must be interpreted with caution, as they can be produced by other disorders. Other potential biopsy sites include peripheral lymph nodes and minor salivary glands.

Conjunctival biopsies are positive in 25–57% of patients with histologically documented sarcoidosis. Variations in these reports are the result of whether clinically evident lesions are biopsied or whether a “blind” conjunctival biopsy is performed. However, the yield can be increased by techniques such as bilateral conjunctival biopsies and serial sectioning of the specimens, and careful inspection of the conjunctiva for any visibly evident nodules which can be biopsied. Transconjunctival lacrimal gland biopsy can also be used for histologic diagnosis, but the procedure is not performed routinely.42,51

Immunology

The Kveim skin test was a simple, specific, outpatient skin test using human sarcoid tissue. It was positive in 78% of patients with sarcoidosis and was helpful in delineating multisystemic sarcoidosis from other granulomatous disorders. The antigen was a saline suspension of human sarcoid tissue prepared from the spleen of a patient suffering from active sarcoidosis. This material was injected intradermally, and the site inspected for nodule formation after 3–6 weeks. A palpable nodule was biopsied, and the finding of noncaseating granulomas on biopsy established the diagnosis of sarcoid.19,52,53 Concerns about the injection of human tissue, with its potential for disease transmission, have essentially eliminated the use of the Kveim test.

Noninvasive tests

Multiple attempts have been made to find noninvasive tests that could be both sensitive and specific in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. These have included measurement of serum calcium, urinary calcium, serum lysozyme, and serum immunoglobulins. Although all these may be abnormal in patients with sarcoid, they are nonspecific and nondiagnostic. The serum ACE level has been touted as a useful measurement in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. The ACE level is frequently abnormal in patients with active sarcoidosis and appears to reflect the total-body granuloma content in such patients. As such, it may be useful in following patients with active sarcoid.43,52,54 However, it is not diagnostic of sarcoidosis and appears to be of limited utility in the diagnostic dilemma of patients with possible sarcoid uveitis but a normal chest film.

For following patients with active intrapulmonary sarcoid, pulmonary function tests, particularly forced vital capacity, forced expiratory volume, and diffusing capacity, are far more useful. Changes in pulmonary function tests are often used to follow patients with sarcoidosis and to adjust the corticosteroid dosage.27

Jabs and Johns55 reported that over 80% of patients with ocular sarcoid had their ocular lesions at the time of diagnosis of sarcoidosis, and Hunter and Foster48 reported that 3% of patients with uveitis were diagnosed as having sarcoid after the initial evaluation for a systemic disease revealed no diagnosable systemic disorder. Although patients who present with uveitis should be evaluated for sarcoid, repetitive workups appear to have limited value unless new symptoms arise.

Course and prognosis

There appear to be two distinct paradigms of sarcoidosis, acute and chronic, with differences in onset, natural history, course, prognosis, and response to treatment. Acute sarcoidosis tends to have an abrupt, explosive onset in young patients and to go into spontaneous remission within 2 years of onset. Acute iritis is often seen in acute sarcoidosis. The response to systemic corticosteroids is generally quite good, and the long-term complications are minimal. Löfgren’s syndrome comprises erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar adenopathy, and acute iritis; it generally has a good long-term prognosis.1,19,29

Chronic sarcoidosis is defined as disease persistence of greater than 2 years. The disease may have a more insidious onset and generally has intrapulmonary involvement with chronic pulmonary disease as a major source of morbidity. Corticosteroid therapy is generally required and may be prolonged. Chronic ocular disease, particularly chronic uveitis, may be a feature of chronic sarcoidosis.1,19,27,29,55

The overall mortality from sarcoidosis is 3–5%, but neurosarcoid is associated with a mortality of 10%.47 Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment, although antimalarial agents can be used for patients with mucocutaneous lesions. Patients with hilar adenopathy without abnormalities of pulmonary function and without intrapulmonary infiltration may not need systemic corticosteroid treatment.

Ocular manifestations

Multiple studies have documented the common occurrence of ocular involvement in sarcoidosis and the various ocular manifestations of sarcoid. Frequency estimates vary and have ranged as high as 50%.47 However, most series report rates that are generally closer to 15–28%.1,19,29,32,55,56 These differences undoubtedly relate to case ascertainment methods, the patient population studied, definitions of ophthalmic involvement, and the nature of the evaluation conducted. Racial differences influence not only the mode of presentation for ocular sarcoidosis but also the frequency of patients with ocular involvement. When the same diagnostic criteria were applied, Japanese patients with sarcoidosis were found to have ocular disease six times more frequently than Finnish patients, and they were also more likely to present with ocular symptoms of sarcoidosis. In the USA, the African American population is twice as likely to have ocular disease as opposed to caucasian patients. Furthermore, high frequencies of ocular involvement are reported when keratoconjunctivitis sicca is sought carefully and included as evidence of lacrimal involvement in sarcoidosis.47

Sarcoidosis may affect most of the ocular structures, as well as the orbit and adnexa. Ocular lesions described in sarcoidosis include: anterior uveitis, iris nodules, conjunctival nodules, scleral nodule,57 and corneal disease with either band keratopathy or interstitial keratitis; posterior segment disease, including chorioretinitis, periphlebitis, chorioretinal nodules, vitreous inflammation, and retinal neovascularization; and orbital disease, including involvement of the lacrimal gland, nasolacrimal duct, optic nerve, and orbital granulomas. The various ocular lesions along with the prevalence estimates are outlined in Table 78.3.

| Ocular manifestations | Frequency in patients with ocular sarcoid (%) |

|---|---|

| Anterior segment disease | |

| Anterior uveitis | 66–70 |

| Acute | 15–32 |

| Chronic | 39–53 |

| Iris nodules | 11–16 |

| Conjunctival lesions | 7–47 |

| Cornea | |

| Band keratopathy | 5–14 |

| Interstitial keratitis | 1 |

| Posterior segment disease | |

| Vitritis | 3–25 |

| Periphlebitis | 10–17 |

| Chorioretinitis | 11 |

| Choroidal nodules | 4–5 |

| Retinal neovascularization | 1–5 |

| Orbital and other disease | 26 |

| Lacrimal gland | 7–60 |

| Keratoconjunctivitis sicca | 5–60 |

| Enlargement | 7–28 |

| Orbital granuloma | 1 |

| Optic nerve granuloma | <1–7 |

The frequency of orbital, and particularly lacrimal gland, lesions varies widely among series and depends on the patient selection and investigations used. Clinical enlargement is present in less than one-third of patients with ocular sarcoid, but when sought, keratoconjunctivitis sicca may be present in a greater percentage.29,32,47,55–57 Orbital granuloma, independent of the lacrimal gland, occurs infrequently.58–60 Massive lacrimal gland enlargement simulating a lacrimal gland tumor may occur and require biopsy.

Posterior segment disease

Posterior segment lesions are reported to occur in approximately 14–28% of patients with ocular sarcoid.6,13,29,32,46,47,55,56,61,62 The actual frequency may be higher, since most patients with posterior segment disease also have anterior uveitis. Posterior lesions include vitritis, chorioretinitis, periphlebitis, vascular occlusion, retinal neovascularization, and optic nerve head granulomas.

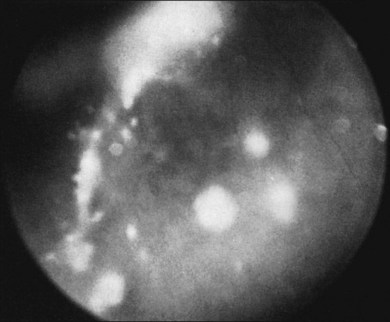

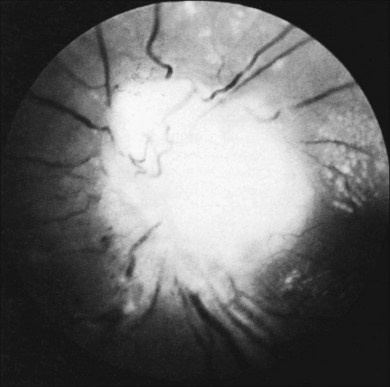

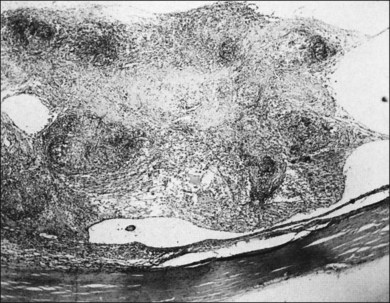

Vitreous infiltration in patients with sarcoidosis can appear as cellular infiltration, often as a nonspecific vitritis. More classically, however, the lesions demonstrate clumping and an accumulation of vitreous debris, called either “snowballs” or a “string of pearls” (Fig. 78.1). These lesions may be somewhat similar in appearance to those seen in pars planitis, although snowball formation is generally not seen in sarcoid uveitis. Sarcoid granulomata can also present in the optic nerve, peripheral retina, pars plana, and anterior choroid, and can be imaged by high-resolution ultrasound biomicroscopy as different forms of uveal thickening.63

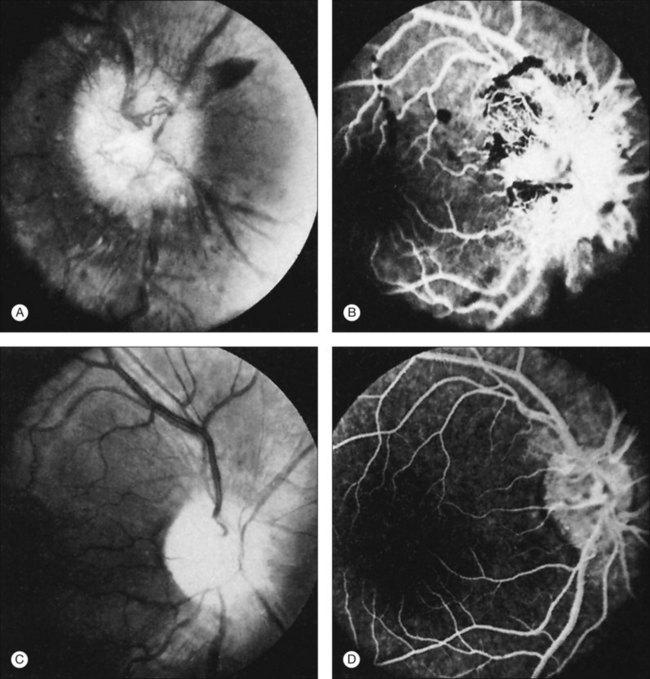

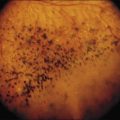

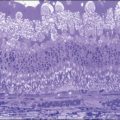

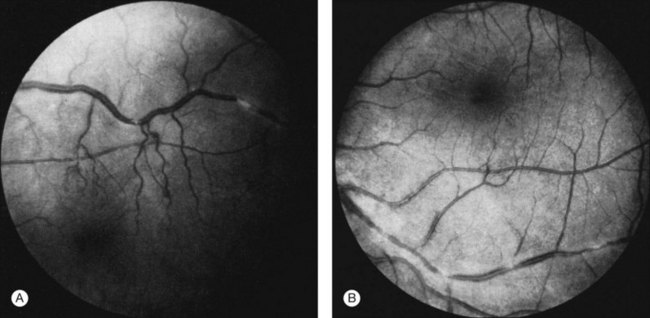

Perivascular sheathing is the second most common finding and occurs in 10–17% of patients with ocular sarcoid. It is generally a midperipheral periphlebitis without significant vascular occlusion (Figs 78.2 and 78.3). However, several series have documented the occasional occurrence of occlusive retinal vascular disease, particularly branch retinal vein occlusion (Fig. 78.4). Central retinal vein occlusion is less common. Histologic studies have demonstrated vascular compromise by the granulomatous inflammatory material.64,65 More severe forms of periphlebitis have been called “candle-wax drippings.” Sanders and Shilling66 have described an “acute retinopathy of sarcoidosis” with extensive perivascular sheathing, vascular occlusion, and intraretinal hemorrhages. These cases were complicated by subsequent retinal neovascularization.

Fig. 78.2 (A and B) Perivascular sheathing in a patient with sarcoidosis.

(Reproduced with permission from Green WR. Inflammatory diseases and conditions of the eye. In: Spencer WH, editor. Ophthalmic pathology: an atlas and textbook, vol. 3. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1986.)

Fig. 78.3 Histopathology of periphlebitis in a patient with sarcoidosis (periodic acid–Schiff reaction; ×225).

(Reproduced with permission from Green WR. Inflammatory diseases and conditions of the eye. In: Spencer WH, editor. Ophthalmic pathology: an atlas and textbook, vol. 3. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1986.)

Deeper chorioretinal lesions have also been reported. These can vary in size from small “Dalen–Fuchs-like” granulomas to large choroidal nodules simulating a metastatic tumor. If located in the macular region, these lesions can cause severe visual loss. Corticosteroid therapy has been able to shrink these lesions. Exudative retinal detachments are rarely seen in patients with sarcoid uveitis but do occur in those patients with large nodular chorioretinal granulomas. These detachments appear to be an overlying detachment of the neurosensory retina and may resolve with oral corticosteroid therapy.5,67

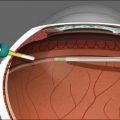

Visual loss can occur from epiretinal membrane formation and cystoid macular edema in patients with sarcoidosis. Once the inflammation has been controlled, pars plana vitrectomy with membrane peeling may have a beneficial effect on restoring vision, although development of cataract and membrane recurrence may require additional surgeries.68,69 In one small uncontrolled case series, triamcinolone acetonide was injected into the vitreous cavity to assist the visualization of the vitreous for the vitrectomy,70 but the role of this approach is uncertain.

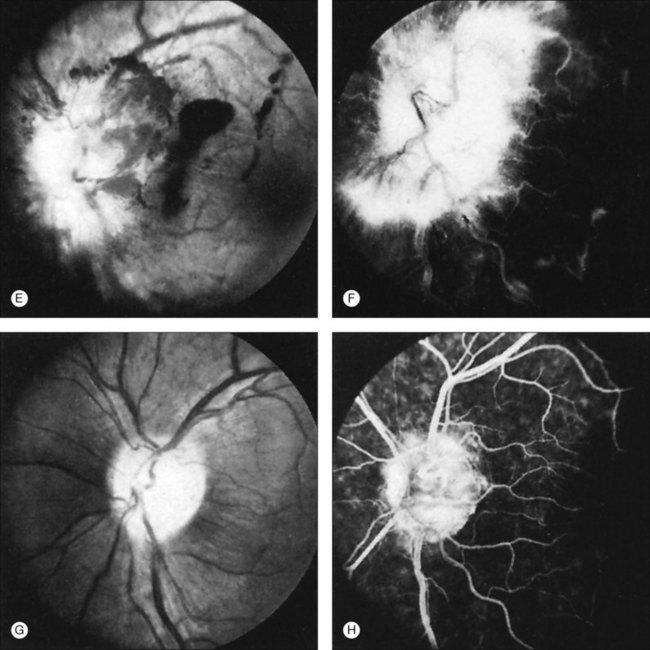

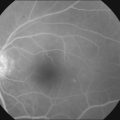

Peripheral retinal neovascularization or neovascularization of the optic nerve head is present in less than 5% of patients with ocular sarcoid, but can be associated with significant visual loss due to vitreous hemorrhage. Peripheral retinal neovascularization is generally seen in patients with a defined vaso-occlusive disorder such as a branch retinal vein occlusion. The peripheral neovascular lesions may even simulate a sea fan, similar to that seen in sickle-cell disease. Neovascularization of the disc may also develop after a branch or central vein occlusion. The rare occurrence of peripapillary choroidal neovascularization in the absence of uveitis or optic nerve disease has been reported, and described to be responsive to oral corticosteroids.70 Doxanas and coworkers71 described a patient with sarcoidosis and a steroid-responsive neovascularization of the optic nerve head without retinal nonperfusion (Fig. 78.5). Hoogstede and Copper65 described one case of subretinal neovascularization, which they attributed to sarcoid uveitis. Duker et al.72 reported the clinical features of proliferative sarcoid retinopathy in 11 eyes of seven patients. In these cases the new retinal vessels were associated with concomitant peripheral retinal capillary nonperfusion. The authors suggested that in these patients capillary nonperfusion secondary to microvascular shutdown, rather than a direct effect of inflammation, was the stimulus for the formation of retinal neovascularization.

It has been reported that when posterior-segment involvement is seen in patients with sarcoid uveitis, there is an increased frequency of CNS involvement. In a retrospective review of the literature, Gould and Kaufman73 suggested that the prevalence of CNS involvement increased from 2% to 30% when fundus lesions were found. However, Spalton and Sanders74 found no such association, thus leaving the association not well confirmed.

Optic nerve involvement, particularly multiple granulomas of the optic nerve head, occur in 0.5–7.0% of patients with ocular sarcoid29,32,53,55,74 (Fig. 78.6). Histologic descriptions have shown granuloma formation53,75 (Fig. 78.7). Optic disc edema without granulomatous invasion of the optic nerve head may be seen in patients either with chronic uveitis or with papilledema34 from CNS sarcoid. Occasionally, isolated sarcoid optic neuropathy (optic atrophy, optic neuritis, optic disc edema) may occur and may be the first manifestation of neurosarcoidosis.76–78

In addition to these conventionally observable lesions, Mizuno and Takahashi79 have used cycloscopy to document the common occurrence of lesions in the ciliary processes of patients with intraocular sarcoidosis. In their series, nodules of the ciliary processes were seen in 41% of eyes, waxy exudates in 24%, and cyclitic membrane-like exudates in 3%. Only 20% of eyes with intraocular sarcoid had no observable lesions.

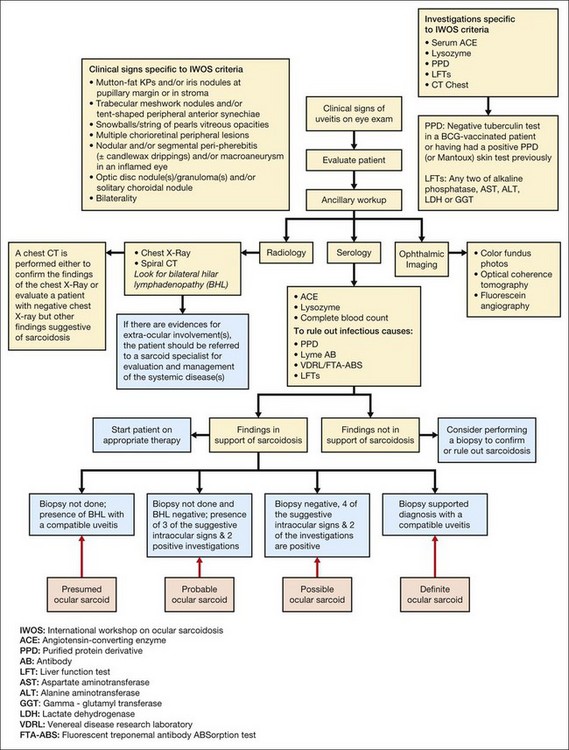

Diagnosis

Ocular sarcoidosis can present as a myraid of signs and symptoms. Such variability in presentation makes the diagnosis challenging and clinicians often need to resort to invasive diagnostic techniques in order to rule out or establish the diagnosis. In 2006 the scientific community came together at the first International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS) in Tokyo, Japan and established criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis when ocular changes are present in the presence or absence of clinical signs of systemic disease. The IWOS diagnostic criteria consist of seven clinical and five laboratory investigations. The IWOS diagnostic criteria allow ophthalmologists to arrive at one of the following four conclusions with a minimally invasive approach: (1) definite; (2) presumed; (3) probable; and (4) possible ocular sarcoidosis. A summary of the IWOS diagnostic criteria and laboratory investigation is given in Table 78.4. A proposed outline to the approach in evaluating a patient for possible ocular sarcoid is shown in Fig. 78.8.

Table 78.4 Clinical signs, laboratory investigations, and diagnostic criteria proposed by the International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis

BCG, bacille Calmette-Guérin; PPD, purified protein derivative; ASAT, aspartate aminotransferase; ALAT, alanine aminotranseferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; γ-GT, glutamyl transferase.

One concern that ophthalmologists may have using the IWOS criteria would be that it was developed based on the information available from the Japanese population and the criteria may not be valid in other ethnicities. However, results from a recent survey of 24 uveitis specialists from around the world suggest that a significant number of ophthalmologists use the IWOS criteria to establish a diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis.80 Employing the IWOS diagnostic criteria allows for diagnosis in the absence of a biopsy, provides information for both the clinician and patient with regard to prognosis, and encourages nonspecialists to consider sarcoidosis as a putative diagnosis. Although there are limitations of the IWOS diagnostic criteria, they certainly help to limit the investigations that a patient with suspected sarcoidosis may have to undergo and help the caregiver to formulate a standardized approach towards establishing the diagnosis.

Course and prognosis

Karma and coworkers56 classified the course of ocular sarcoidosis as monophasic, relapsing, or chronic. The three different courses of uveitis correlated with visual outcome. Patients with monophasic uveitis retained 20/30 or better visual acuity in 88% of eyes, with relapsing uveitis in 72% of eyes, and with chronic uveitis in none of the six eyes. Similarly, those with monophasic uveitis had a visual acuity of 20/70 or worse in 12% of eyes, with relapsing uveitis in 28% of eyes, and chronic uveitis in 67% of eyes. Hence the course of uveitis appears to correlate with the long-term visual outcome.

The development of secondary glaucoma in association with sarcoid uveitis appears to be a poor prognostic sign and is associated with severe visual loss. In one series,55 most of these patients had a panuveitis with both anterior- and posterior-segment involvement associated with the development of secondary glaucoma, suggesting a more severe ocular disease. Treatment should be directed towards promptly suppressing the inflammation and minimizing any potential ocular complications.

In a retrospective study of 60 patients with sarcoid-associated uveitis who were followed at a subspecialty eye care and referral center, Dana et al.81 identified prognostic factors for visual outcomes in sarcoid uveitis. The factors most strongly associated with both a lack of visual acuity improvement and a final visual acuity worse than 20/40 were: (1) delay in presentation to a uveitis subspecialist of greater than 1 year; (2) development of glaucoma; and (3) presence of intermediate or posterior uveitis. There was a substantial increase in the relative odds of both visual improvement and the likelihood of achieving a visual acuity of at least 20/40 among patients in whom systemic corticosteroids were used for treatment. Because patients with more severe disease are more likely to receive systemic corticosteroid therapy, this result strongly supports the use of systemic corticosteroids for selected patients with sarcoid uveitis. Miserocchi et al. evaluated the risk factors for visual outcomes in 44 patients retrospectively and their multivariate results suggest that only the presence of cystoid macular edema was significantly associated with worse visual outcome.82

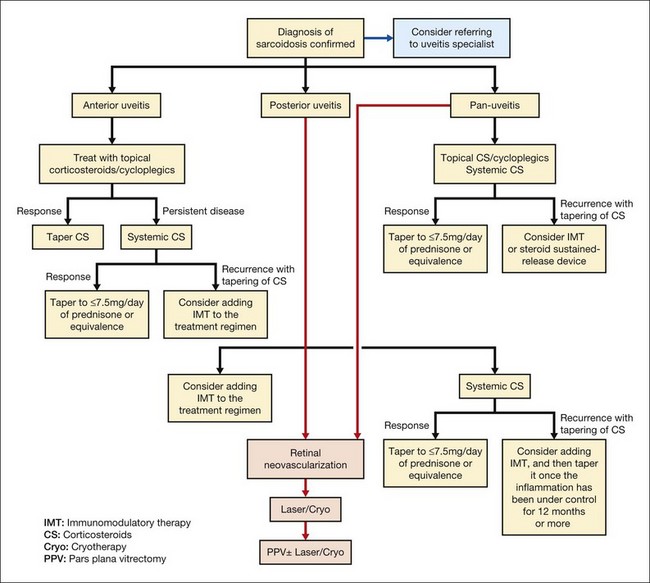

Therapy

Treatment of any form of uveitis depends upon the initial presentation of the patient, severity of the disease, and accompanied complications. Nonetheless, the goals of therapy remain the same and include preservation of visual acuity, prompt identification of all sources of inflammation, zero tolerance toward any degree of inflammation, and proper management of complications such as macular edema, cataract, and glaucoma. The management of uveitis can be quite complex and may involve employment of multiple therapeutic options, some of which do have potential significant and serious side-effects. Timely referral to uveitis specialists is of the utmost priority and importance to allow correct diagnosis, and prompt and aggressive treatment with appropriate therapeutic agents, which may help to preserve vision and reduce the risks of irreversible ocular injury secondary to cumulative damage in patients with uveitis. A proposed outline for the management of ocular sarcoidosis is shown in Fig. 78.9. However, it is of the utmost importance to recognize that the approach to the management of each patient should be individualized. The proposed scheme only serves as a generalized recommendation. If there are any concerns regarding the diagnosis and management of a patient with ocular sarcoidosis, it may be beneficial for the patient if he/she can be referred to a uveitis specialist who is experienced in managing the disease.

Established therapy

Although corticosteroids are very effective in controlling inflammation initially, their long-term use is often associated with significant complications and side-effects. The use of steroid-sparing agents is indicated if chronic steroid usage (≥7.5 mg of prednisone or equivalent daily) is required to control the inflammation. Occasionally, corticosteroid-sparing agents such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclosporine may be useful in patients with corticosteroid-dependent sarcoidosis in whom corticosteroid side-effects are problematic;83–86 however, their usages may not be without risk. Patients being treated with these agents, including corticosteroids, require very thorough and experienced clinical oversight by specialists (such as uveitis specialists, rheumatologists, or oncologists) who are familiar with employing such classes of drugs.

More recently, methotrexate,87 azathioprine,88,89 and mycophenolate90 have been widely employed as steroid-sparing agents in the management of chronic uveitis. In a retrospective series of 386 patients, methotrexate was found to control uveitis in 66% of patients.91 However, in 16% of patients, toxicity and adverse events secondary to the drug led to its discontinuation. A delay of up to 6 months in response to therapy with methotrexate has also been reported, which has prompted the use of intraocular injections of the drug.88 Azathioprine has been reported to be beneficial in patients with ocular sarcoidosis who do not respond to methotrexate. However, in a retrospective study of patients with intermediate uveitis, a 25% rate of discontinuation was noted within the first year of therapy due to toxicity. Mycophenolate mofetil has shown promising results in terms of low toxicity. Deuter et al.90 reported a success rate of 86% in patients with chronic uveitis treated with mycophenolate with a discontinuation of only 5% due to toxicity. A small series of seven patients diagnosed with sarcoidosis has also reported the drug to be beneficial.92 Galor et al. reported a response rate of 70%, 42%, and 58% at 6 months for mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, and azathioprine, respectively, in 321 patients with nonspecific ocular inflammation.93 Although the time to response for azathioprine and mycophenolate was similar, the former had more toxicity-related events reported.

Other immunomodulatory therapeutic agents have been employed in the management of sarcoidosis. Baughman and Lower reported a 58% complete and 28% partial improvement in patients with ocular sarcoidosis when treated with leflunomide. Only two of the 28 patients discontinued therapy due to toxicity in this study.94

Biologics

Biologics, antagonists of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) such as adalimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody), infliximab (chimeric monoclonoal antibody), and etanercept (soluble TNF receptor antagonist) have been reported in small studies to benefit patients with chronic uveitis.95–99 However, there is a lack of evidence from RCTs supporting the use of adalimumab and infliximab, while it has been shown in a double-masked RCT that etanercept is no better than placebo when treating chronic uveitis.61,62 Several groups have also reported the development of uveitis in patients receiving anti-TNF therapy,98,100,101 at a significantly higher rate, with etanercept followed by infliximab and adalimumab.102 Although the mechanism of this phenomenon is not yet fully understood, several reports of anti-TNF therapy leading to a sarcoidosis-like reaction suggest that a very cautious approach should be taken when using these agents to treat ocular sarcoidosis.

1 James DG, Neville E, Siltzbach LE. A worldwide review of sarcoidosis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1976;278:321–334.

2 James DG. Sarcoidosis. Wyngaarden JB, Smith LH, Jr. Cecil textbook of medicine, 17th ed, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1985.

3 Henderly DE, Genstler AJ, Smith RE, et al. Changing patterns of uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103:131–136.

4 Karma A. Ophthalmic changes in sarcoidosis. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 1979:1–94.

5 Perkins ES, Folk J. Uveitis in London and Iowa. Ophthalmologica. 1984;189:36–40.

6 Rosenbaum JT. Uveitis. An internist’s view. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1173–1176.

7 Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736–755.

8 Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J, Jr., et al. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:234–241.

9 Lazarus A. Sarcoidosis: epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, and genetics. Dis Mon. 2009;55:649–660.

10 James DG, Neville E, Siltzbach LE. A worldwide review of sarcoidosis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1976;278:321–334.

11 Rosenberg AM, Yee EH, Mackenzie JW. Arthritis in childhood sarcoidosis. J Rheumatol. 1983;10:987–990.

12 Seamone CD, Nozik RA. Sarcoidosis and the eye. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 1992;5:567–576.

13 Milman N, Hoffmann AL. Childhood sarcoidosis: long-term follow-up. Eur Respire J. 2008;31:592–598.

14 Blain JG, Riley W, Logothetis J. Optic nerve manifestations of sarcoidosis. Arch Neurol. 1965;13:307–309.

15 Jabs DA, Houk JL, Bias WB, et al. Familial granulomatous synovitis, uveitis, and cranial neuropathies. Am J Med. 1985;78:801–804.

16 Rose CD, Eichenfield AH, Goldsmith DP, et al. Early onset sarcoidosis with aortitis – “juvenile systemic granulomatosis?”. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:102–106.

17 Scerri L, Cook LJ, Jenkins EA, et al. Familial juvenile systemic granulomatosis (Blau’s syndrome). Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:445–448.

18 Latkany PA, Jabs DA, Smith Justine R, et al. Multifocal choroiditis in patients with familial juvenile systemic granulomatosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:897–904.

19 James DG. Sarcoidosis. Wyngaarden JB, Smith LH, Jr. Cecil textbook of medicine, 17th ed, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1985.

20 Rossman MD, Thompson B, Frederick M, et al. HLA-DRB1*1101: a significant risk factor for sarcoidosis in blacks and whites. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:720–735.

21 Crystal RG, Roberts WC, Hunninghake GW, et al. NIH conference. Pulmonary sarcoidosis: a disease characterized and perpetuated by activated lung T-lymphocytes. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:73–94.

22 Hunninghake GW, Crystal RG. Pulmonary sarcoidosis: a disorder mediated by excess helper T-lymphocyte activity at sites of disease activity. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:429–434.

23 Meyer KC, Kaminski MJ, Calhoun WJ, et al. Studies of bronchoalveolar lavage cells and fluids in pulmonary sarcoidosis. I. Enhanced capacity of bronchoalveolar lavage cells from patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis to induce angiogenesis in vivo. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:1446–1449.

24 Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. T-cell subsets in cutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:728–732.

25 Chan CC, Wetzig RP, Palestine AG, et al. Immunohistopathology of ocular sarcoidosis. Report of a case and discussion of immunopathogenesis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:1398–1402.

26 Semenzato G, Agostini C, Zambello R, et al. Activated T-cells with immunoregulatory functions at different sites of involvement in sarcoidosis – phenotypic and functional evaluations. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1986;465:56–73.

27 Johns CJ, Schonfeld SA, Scott PP, et al. Longitudinal study of chronic sarcoidosis with low-dose maintenance corticosteroid therapy. Outcome and complications. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1986;465:702–712.

28 Mayock RL, Bertrand P, Morrison CE, et al. Manifestations of sarcoidosis. Analysis of 145 patients, with a review of nine series selected from the literature. Am J Med. 1963;35:67–89.

29 James DG. Ocular sarcoidosis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1986;465:551–563.

30 Mana J, Marcoval J, Graells J, et al. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis. Relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882–888.

31 Zarei M, Anderson JR, Higgins JN, et al. Cavernous sinus syndrome as the only manifestation of sarcoidosis. J Postgrad Med. 2002;48:119–121.

32 Obenauf CD, Shaw HE, Sydnor CF, et al. Sarcoidosis and its ophthalmic manifestations. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;86:648–655.

33 Delaney P. Neurologic manifestations in sarcoidosis: review of the literature, with a report of 23 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1977;87:336–345.

34 James DG, Zatouroff MA, Trowell J, et al. Papilloedema in sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1967;51:526–529.

35 Sugo A, Seyama K, Yaguchi T, et al. [Cardiac sarcoidosis with myopathy and advanced A-V nodal block in a woman with a previous diagnosis of sarcoidosis.]. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1995;33:1111–1118.

36 Wilson AG, Hansell DM. Immunologic diseases of the lung. In: Armstrong P, Wilson AG, Hansell DM. Imaging of the diseases of the chest. London: Mosby; 2000:637–688.

37 Nishino M, Lee KS, Itoh H, et al. The spectrum of pulmonary sarcoidosis: variations of high-resolution CT findings and clues for specific diagnosis. Eur J Radiol. 2010;73:66–73.

38 Nakatsu M, Hatabu H, Morikawa K, et al. Large coalescent parenchymal nodules in pulmonary sarcoidosis: “sarcoid galaxy” sign. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178(6):1389–1393.

39 Terasaki H, Fujimoto K, Muller NL, et al. Pulmonary sarcoidosis: comparison of findings of inspiratory and expiratory high-resolution CT and pulmonary function tests between smokers and nonsmokers. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:333–338.

40 Davies CW, Tasker AD, Padley SP, et al. Air trapping in sarcoidosis on computed tomography: correlation with lung function. Clin Radiol. 2000;55:217–221.

41 Nosal A, Schleissner LA, Mishkin FS, et al. Angiotensin-I-converting enzyme and gallium scan in noninvasive evaluation of sarcoidosis. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90:328–331.

42 Weinreb RN. Diagnosing sarcoidosis by transconjunctival biopsy of the lacrimal gland. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;97:573–576.

43 Rohatgi PK, Ryan JW, Lindeman P. Value of serial measurement of serum angiotensin converting enzyme in the management of sarcoidosis. Am J Med. 1981;70:44–50.

44 Power WJ, Neves RA, Rodriguez A, et al. The value of combined serum angiotensin-converting enzyme and gallium scan in diagnosing ocular sarcoidosis. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:2007–2011.

45 Akbar JJ, Meyer CA, Shipley RT, et al. Cardiopulmonary imaging in sarcoidosis. Clin chest med. 2008;29:429–443. viii

46 Mana J. Magnetic resonance imaging and nuclear imaging in sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2002;8:457–463.

47 Crick RP, Hoyle C, Smellie H. The eyes in sarcoidosis. Br j ophthalmol. 1961;45:461–481.

48 Hunter DG, Foster CS. Isolated ocular sarcoidosis – late development of systemic manifestations in uveitis patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 32, 1991. 681–681

49 Tremblay A, Stather DR, Maceachern P, et al. A randomized controlled trial of standard vs endobronchial ultrasonography-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in patients with suspected sarcoidosis. Chest. 2009;136:340–346.

50 Annema JT, Veselic M, Rabe KF. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:405–409.

51 Weinreb RN, Tessler H. Laboratory diagnosis of ophthalmic sarcoidosis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1984;28:653–664.

52 Israel HL, Sones M. Selection of biopsy procedures for sarcoidosis diagnosis. Arch Intern Med. 1964;113:255–260.

53 Green WR. Inflammatory disease and conditions of the eye. In: Spencer WH, ed. Ophthalmic pathology: an atlas and textbook. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1986.

54 Baarsma GS, La Hey E, Glasius E, et al. The predictive value of serum angiotensin converting enzyme and lysozyme levels in the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:211–217.

55 Jabs DA, Johns CJ. Ocular involvement in chronic sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;102:297–301.

56 Karma A, Huhti E, Poukkula A. Course and outcome of ocular sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:467–472.

57 Qazi FA, Thorne JE, Jabs DA. Scleral nodule associated with sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:752–754.

58 Khan JA, Hoover DL, Giangiacomo J, et al. Orbital and childhood sarcoidosis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1986;23:190–194.

59 Collison JM, Miller NR, Green WR. Involvement of orbital tissues by sarcoid. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;102:302–307.

60 Faller M, Purohit A, Kennel N, et al. Systemic sarcoidosis initially presenting as an orbital tumour. Eur Respir J. 1996:474–476.

61 Foster CS, Tufail F, Waheed NK, et al. Efficacy of etanercept in preventing relapse of uveitis controlled by methotrexate. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:437–440.

62 Smith JA, Thompson DJ, Whitcup SM, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-masked clinical trial of etanercept for the treatment of uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:18–23.

63 Gentile RC, Berinstein DM, Liebmann J, et al. High-resolution ultrasound biomicroscopy of the pars plana and peripheral retina. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:478–484.

64 Gass JD, Olson CL. Sarcoidosis with optic nerve and retinal involvement. Arch Ophthalmol. 1976;94:945–950.

65 Hoogstede HA, Copper AC. A case of macular subretinal neovascularisation in chronic uveitis probably caused by sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1982;66:530–535.

66 Sanders MD, Shilling JS. Retinal, choroidal, and optic disc involvement in sarcoidosis. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK. 1976;96:140–144.

67 Letocha CE, Shields JA, Goldberg RE. Retinal changes in sarcoidosis. Can J Ophthalmol. 1975;10:184–192.

68 Kiryu J, Kita M, Tanabe T, et al. Pars plana vitrectomy for cystoid macular edema secondary to sarcoid uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1140–1144.

69 Kiryu J, Kita M, Tanabe T, et al. Pars plana vitrectomy for epiretinal membrane associated with sarcoidosis. Jpn J ophthalmol. 2003;47:479–483.

70 Sonoda KH, Enaida H, Ueno A, et al. Pars plana vitrectomy assisted by triamcinolone acetonide for refractory uveitis: a case series study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:1010–1014.

71 Doxanas MT, Kelley JS, Prout TE. Sarcoidosis with neovascularization of the optic nerve head. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90:347–351.

72 Duker JS, Brown GC, McNamara JA. Proliferative sarcoid retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:1680–1686.

73 Gould H, Kaufman HE. Sarcoid of the fundus. Arch Ophthalmol. 1961;65:453–456.

74 Spalton DJ, Sanders MD. Fundus changes in histologically confirmed sarcoidosis. Br J ophthalmol. 1981;65:348–358.

75 Kelley JS, Green WR. Sarcoidosis involving the optic nerve head. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;89:486–488.

76 Ing EB, Garrity JA, Cross SA, et al. Sarcoid masquerading as optic nerve sheath meningioma. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:38–43.

77 Katz B. Disc edema, transient obscurations of vision, and a temporal fossa mass. Surv ophthalmol. 1991;36:133–139.

78 Mansour AM. Sarcoid optic disc edema and optociliary shunts. J Clin Neuro-Ophthalmol. 1986;6:47–52.

79 Mizuno K, Takahashi J. Sarcoid cyclitis. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:511–517.

80 Wakefield D, Zierhut M. Controversy: ocular sarcoidosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18:5–9.

81 Dana MR, Merayo-Lloves J, Schaumberg DA, et al. Prognosticators for visual outcome in sarcoid uveitis. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1846–1853.

82 Miserocchi E, Modorati G, Di Matteo F, et al. Visual outcome in ocular sarcoidosis: retrospective evaluation of risk factors. Available online at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21374555 (accessed 03/03/2011)

83 Gedalia A, Molina JF, Ellis GS, et al. Low-dose methotrexate therapy for childhood sarcoidosis. J pediatr. 1997;130:25–29.

84 Kaye O, Palazzo E, Grossin M, et al. Low-dose methotrexate: an effective corticosteroid-sparing agent in the musculoskeletal manifestations of sarcoidosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:642–644.

85 Lower EE, Baughman RP. Prolonged use of methotrexate for sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:846–851.

86 Mathur A, Kremer JM. Immunopathology, rheumatic features, and therapy of sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1992;4:76–80.

87 Samson CM, Waheed N, Baltatzis S, et al. Methotrexate therapy for chronic noninfectious uveitis: analysis of a case series of 160 patients. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1134–1139.

88 Taylor SR, Habot-Wilner Z, Pacheco P, et al. Intraocular methotrexate in the treatment of uveitis and uveitic cystoid macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:797–801.

89 Muller-Quernheim J, Kienast K, Held M, et al. Treatment of chronic sarcoidosis with an azathioprine/prednisolone regimen. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:1117–1122.

90 Deuter CME, Doycheva D, Stuebiger N, et al. Mycophenolate sodium for immunosuppressive treatment in uveitis. Ocular Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:415–419.

91 Kempen JH, Altaweel MM, Holbrook JT, et al. The multicenter uveitis steroid treatment trial: rationale, design, and baseline characteristics. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:550–561. e10

92 Bhat P, Cervantes-Castaneda RA, Doctor PP, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil therapy for sarcoidosis-associated uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:185–190.

93 Galor A, Perez VL, Hammel JP, et al. Comparison of antimetabolite drugs as corticosteroid-sparing therapy for noninfectious ocular inflammation. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1826–1832.

94 Baughman RP, Lower EE. Leflunomide for chronic sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasculitis Diffuse Lung Dis. 2004;21:43–48.

95 Reiff A, Takei S, Sadeghi S, et al. Etanercept therapy in children with treatment-resistant uveitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1411–1415.

96 Baughman RP, Bradley DA, Lower EE. Infliximab in chronic ocular inflammation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;43:7–11.

97 Galor A, Perez VL, Hammel JP, et al. Differential effectiveness of etanercept and infliximab in the treatment of ocular inflammation. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2317–2323.

98 Tynjala P, Lindahl P, Honkanen V, et al. Infliximab and etanercept in the treatment of chronic uveitis associated with refractory juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:548–550.

99 Diaz-Llopis M, Garcia-Delpech S, Salom D, et al. Adalimumab therapy for refractory uveitis: a pilot study. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2008;24:351–361.

100 Schmeling H, Horneff G. Etanercept and uveitis in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatol (Oxf). 2005;44:1008–1011.

101 Hashkes PJ, Shajrawi I. Sarcoid-related uveitis occurring during etanercept therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21:645–646.

102 Lim LL, Fraunfelder FW, Rosenbaum JT. Do tumor necrosis factor inhibitors cause uveitis? A registry-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3248–3252.

103 Branson JH, Park JH. Sarcoidosishepatic involvement: presentation of a case with fatal liver involvement; including autopsy findings and review of the evidence for sarcoid involvement of the liver as found in the literature. Ann Intern Med. 1954;40:111–145.

104 Klatskin G. Hepatic granulomata: problems in interpretation. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1976;278:427–432.

105 Beahrs OH, Woolner LB, Kirklin JW, et al. Carcinomatous transformation of mixed tumors of the parotid gland. AMA Arch Surg. 1957;75:605–613. discussion 604–13

106 Rochlin DB, Enterline HT. Prescalene lymph node biopsies; a report of 142 cases. Am J Surg. 1958;96:372–378.

107 Williams TK, Webb WR. Prescalene node biopsy. An evaluation. Arch Surg. 1962;84:261–264.

108 Romer F, Paulsen S, Antonius V, et al. Sarcoidosis in a Danish “amt”. A retrospective epidemiologic study of sarcoidosis in Ringkobing Amt from 1960 to 1969. Dan Med Bull. 1973;20:112–120.

109 Rasmussen SM, Neukirch F. Sarcoidosis. A clinical study with special reference to the choice of biopsy procedure. Acta Med Scand. 1976;199:209–216.

110 Carlens E. Biopsies in connection with bronchoscopy and mediastinoscopy in sarcoidosis; a comparison. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1964;425:237–238.

111 Palva T. Mediastinal sarcoidosis. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1964;188:258.

112 Koerner SK, Sakowitz AJ, Appelman RI, et al. Transbronchinal lung biopsy for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 1975;293:268–270.

113 Koontz CH. Lung biopsy in sarcoidosis. Chest. 1978;74:120–121.

114 Crick RP, Hoyle C, Smellie H. The eyes in sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1961;45:461–481.

115 Bornstein JS, Frank MI, Radner DB. Conjunctival biopsy in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 1962;267:60–64.

116 Khan F, Wessely Z, Chazin SR, et al. Conjunctival biopsy in sarcoidosis: A simple, safe, and specific diagnostic procedure. Ann Ophthalmol. 1977;9:671–676.

117 Solomon DA, Horn BR, Byrd RB, et al. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis by conjunctival biopsy. Chest. 1978;74:271–273.

118 Nichols CW, Eagle RC, Jr., Yanoff M, et al. Conjunctival biopsy as an aid in the evaluation of the patient with suspected sarcoidosis. Ophthalmology. 1980;87:287–291.

119 Karcioglu ZA, Brear R. Conjunctival biopsy in sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99:68–73.

120 Nessan VJ, Jacoway JR. Biopsy of minor salivary glands in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:922–924.