Safety in the Hematology Laboratory

After completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Define standard precautions.

2. List infectious materials included in standard precautions.

3. Describe the safe practices required in the Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens Standard.

4. Identify occupational hazards that exist in the hematology laboratory.

5. Identify the requirements of the Occupational Exposure to Hazardous Chemicals in Laboratories Standard.

6. Discuss the development of a safety management program.

7. Describe the principles of a fire prevention program, including details such as the frequency of testing equipment.

8. Name the most important practice to prevent the spread of infection.

9. Given a written laboratory scenario, assess it for safety hazards and recommend corrective action.

10. Select the proper class of fire extinguisher for a given type of fire.

11. Define material safety data sheets (MSDSs), list information contained on MSDSs, and determine when MSDSs would be used in laboratory activity.

12. Name the specific practice during which most needle stick injuries occur.

Case Study

1. A hematology technologist was observed removing gloves and immediately left the laboratory for a meeting. The medical laboratory professional did not remove the laboratory coat.

2. Food was found in the specimen refrigerator.

3. Syringes were found in the proper sharps container. On further investigation, 50% of the attached needles were recapped.

4. Hematology technologists were seen in the lunchroom wearing laboratory coats.

5. Fire extinguishers were found every 75 feet of the laboratory.

6. Fire extinguishers were inspected quarterly and annually.

7. One fire drill was conducted in the last 8 months.

8. Unlabeled bottles were found at the workstation.

9. A 1 : 10 solution of bleach was found near the electronic cell counter. Further investigation revealed that the bleach solution was made 6 months ago.

10. Gloves were worn by the staff receiving specimens.

11. Material safety data sheets were obtained by fax.

12. Chemicals were stored alphabetically.

13. Fifty percent of the staff interviewed had not participated in a fire drill.

Standard Precautions

Applicable Safety Practices Required by the OSHA Standard

The following standards are applicable in a hematology laboratory and must be enforced:

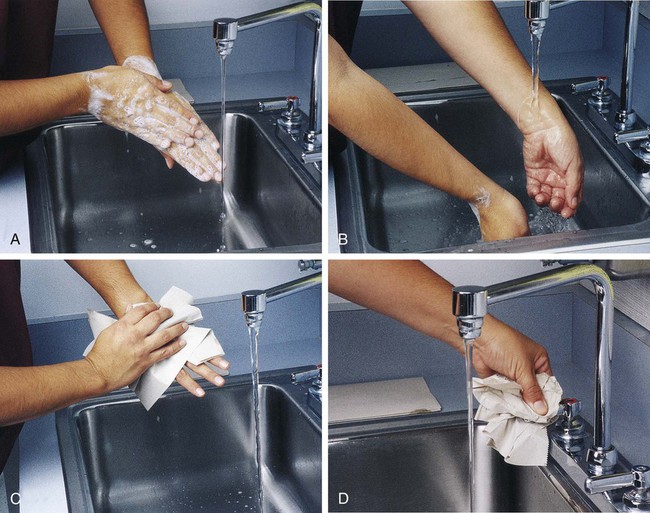

1. Handwashing is one of the most important safety practices. Hands must be washed with soap and water. If water is not readily available, alcohol hand gels (minimum 62% alcohol) may be used. Hands must be thoroughly dried. The proper technique for handwashing is as follows:

a. Wet hands and wrists thoroughly under running water.

b. Apply germicidal soap and rub hands vigorously for at least 15 seconds, including between the fingers and around and over the fingernails (Figure 2-1, A).

c. Rinse hands thoroughly under running water in a downward flow from wrist to fingertips (see Figure 2-1, B).

d. Dry hands with a paper towel (see Figure 2-1, C). Use the paper towel to turn off the faucet handles (see Figure 2-1, D).

a. Whenever there is visible contamination with blood or body fluids

c. After gloves are removed and between glove changes

d. Before leaving the laboratory

e. Before and after eating and drinking, smoking, applying cosmetics or lip balm, changing a contact lens, and using the lavatory

f. Before and after all other activities that entail hand contact with mucous membranes, eyes, or breaks in skin

2. Eating, drinking, smoking, and applying cosmetics or lip balm must be prohibited in the laboratory work area.

3. Hands, pens, and other fomites must be kept away from the worker’s mouth and all mucous membranes.

4. Food and drink, including oral medications and tolerance-testing beverages, must not be kept in the same refrigerator as laboratory specimens or reagents or where potentially infectious materials are stored or tested.

5. Mouth pipetting must be prohibited.

6. Needles and other sharp objects contaminated with blood and other potentially infectious materials should not be manipulated in any way. Such manipulation includes resheathing, bending, clipping, or removing the sharp object. Resheathing or recapping is permitted only when there are no other alternatives or when the recapping is required by specific medical procedures. Recapping is permitted by use of a method other than the traditional two-handed procedure. The one-handed method or a resheathing device is often used (see Chapter 3). Documentation in the exposure control plan should identify the specific procedure by which resheathing is permitted.

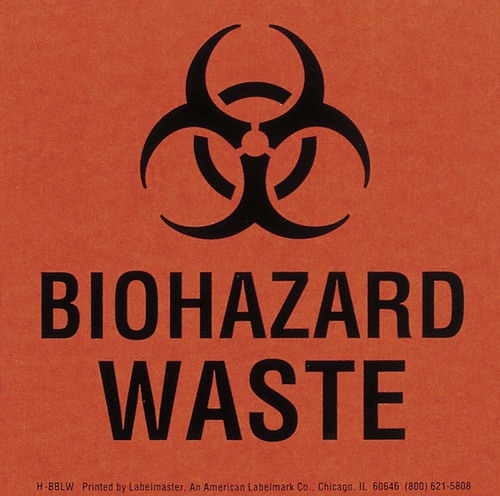

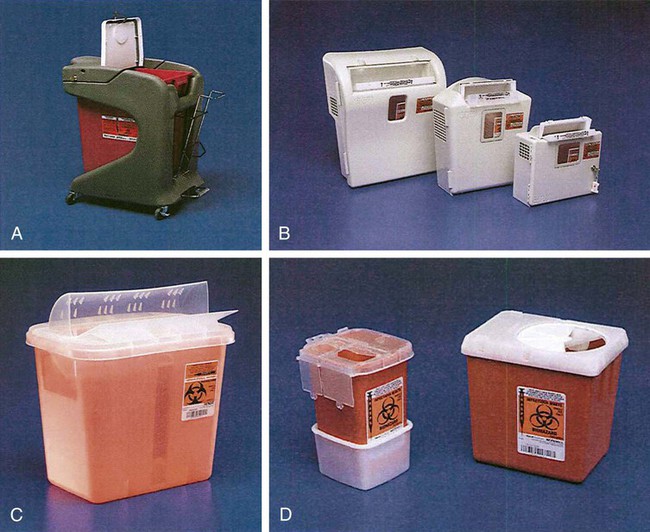

7. Contaminated sharps (including, but not limited to, needles, blades, pipettes, syringes with needles, and glass slides) must be placed in a puncture-resistant container that is appropriately labeled with the universal biohazard symbol (Figure 2-2) or a red container that adheres to the standard. The container must be leak-proof (Figure 2-3).

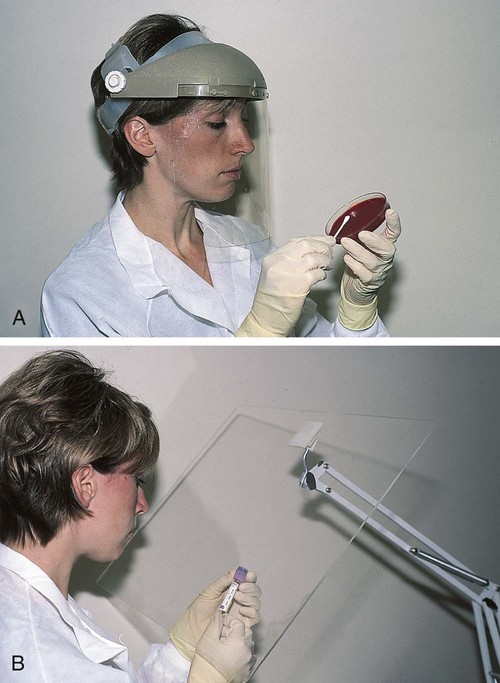

8. Procedures such as removing caps when checking for clots, filling hemacytometer chambers, making slides, discarding specimens, making dilutions, and pouring specimens or fluids must be performed so that splashing, spraying, or production of droplets of the specimen being manipulated is prevented. These procedures may be performed behind a barrier, such as a plastic shield, or protective eyewear should be worn (Figure 2-4).

9. Personal protective clothing and equipment must be provided to the worker. The most common forms of personal protective equipment are described in the following:

a. Outer coverings, including gowns, laboratory coats, and sleeve protectors, should be worn when there is a chance of splashing or spilling on work clothing. The outer covering must be made of fluid-resistant material, must be long-sleeved, and must remain buttoned at all times. If contamination occurs, the personal protective equipment should be removed immediately and treated as infectious material.

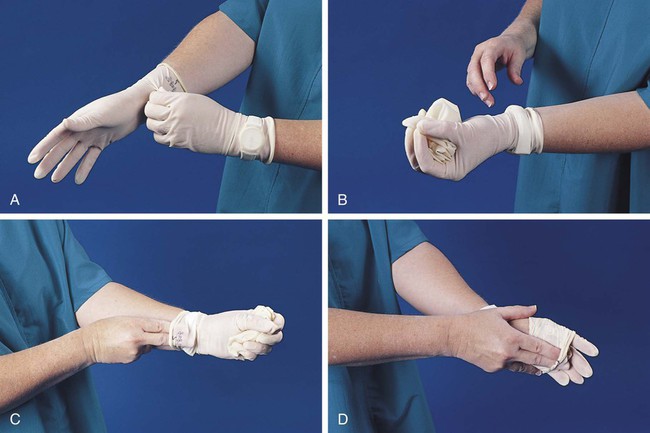

b. Gloves must be worn when the potential for contact with blood or body fluids exists (including when removing and handling bagged biohazardous material and when decontaminating bench tops) and when venipuncture or finger sticks are performed. One of the limitations of gloves is that they do not prevent needle sticks or other puncture wounds. Provision of gloves to laboratory workers must accommodate latex allergies. Alternative gloves must be readily accessible to any laboratory worker with a latex allergy. Gloves must be changed after each contact with a patient, when there is visible contamination, and when physical damage occurs. Gloves should not be worn when “clean” devices, such as a copy machine or a “clean” telephone, are used. Gloves must not be worn again or washed. After one glove is removed, the second glove can be removed by sliding the index finger of the ungloved hand between the glove and the hand and slipping the second glove off. This technique prevents contamination of the “clean” hand by the “dirty” second glove (Figure 2-5).1 Contaminated gloves should be disposed of according to applicable federal or state regulations.

c. Eyewear, including face shields, goggles, and masks, should be used when there is potential for aerosol mists, splashes, or sprays to mucous membranes (mouth, eyes, or nose). Removing caps from specimen tubes, working at the cell counter, and centrifuging specimens are examples of tasks that could result in creation of aerosol mist.

10. Phlebotomy trays should be appropriately labeled to indicate potentially infectious materials. Specimens should be placed into a secondary container, such as a resealable biohazard-labeled bag.

11. If a pneumatic tube system is used to transport specimens, the specimens should be transported in the appropriate tube (primary containment), placed into a special self-sealing leak-proof bag, appropriately labeled with the biohazard symbol (secondary containment). Requisition forms should be placed outside of the secondary container to prevent contamination if the specimen leaks. Foam inserts for the pneumatic tube system carrier prevent shifting of the sample during transport and also act as a shock absorber, thus decreasing the risk of breakage.

12. When equipment used to process specimens becomes visibly contaminated or requires maintenance or service, it must be decontaminated, whether service is performed within the laboratory or by a manufacturer repair service. Decontamination of equipment would consist at a minimum of flushing the lines and wiping the exterior and interior of the equipment. If it is difficult to decontaminate the equipment, it must be labeled with the biohazard symbol to indicate potentially infectious material. Routine cleaning should be performed on equipment that has the potential for receiving splashes or sprays, such as inside the lid of the microhematocrit centrifuge.

Occupational Hazards

Four important occupational hazards in the laboratory are discussed in this chapter: fire hazard, chemical hazards, electrical hazard, and needle puncture. There are other hazards to be considered when a safety management program is developed, and the reader is referred to the Department of Labor section of the Code of Federal Regulations for detailed regulations.2

Fire Hazard

1. Enforcement of a no-smoking policy.

2. Installation of appropriate fire extinguishers. Several types of extinguishers, most of which are multipurpose, are available for use for specific types of fire.

3. Placement of fire extinguishers every 75 feet. A distinct system for marking the locations of fire extinguishers enables quick access when they are needed. Fire extinguishers should be checked monthly and maintained annually. Not all fire extinguishers are alike. Each fire extinguisher is rated for the type of fire that it can suppress. It is important to use the correct fire extinguisher for the given class of fire. Hematology laboratory workers should be trained to recognize the class of extinguisher and to use a fire extinguisher properly. Table 2-1 summarizes the fire extinguisher classifications. The fire extinguishers used in the laboratory are portable extinguishers and are not designed to fight large fires. In the event of a fire in the laboratory, the local fire department must be contacted immediately.

TABLE 2-1

Fire Extinguisher Classifications

| Class/Type of Extinguisher | Type of Fire |

| A | Use class A extinguishers on fires involving ordinary combustibles such as wood, cloth, or paper. |

| B | Use class B extinguishers on fires involving flammable liquids, gases, or grease. |

| C | Use class C extinguishers on energized (plugged-in) electrical fires. Examples are fires involving household appliances, computer equipment, fuse boxes, or circuit breakers. |

| ABC | ABC extinguishers are multipurpose extinguishers that handle type A, B, and C fires. |

4. Placement of adequate fire detection systems (alarms, sprinklers), which should be tested every 3 months.

5. Placement of manual fire alarm boxes near the exit doors. Travel distance should not exceed 200 feet.

6. Written fire prevention and response procedures, commonly referred to as the fire response plan. All staff in the laboratory should be knowledgeable about the procedures. Workers should be given assignments for specific responsibilities in case of fire, including responsibilities for patient care, if applicable. Total count of employees in the laboratory should be known for any given day, and a buddy system should be developed in case evacuation is necessary. Equipment shutdown procedures should be addressed in the plan, as should responsibility for implementation of those procedures.

7. Fire drills, which should be conducted so that response to a fire situation is routine and not a panic response. Frequency of fire drills varies by type of occupancy of the building and by accrediting agency. Overall governance is by the state fire marshall. All laboratory staff members should participate in the fire drills. Proper documentation should be maintained to show that all phases of the fire response plan were activated. If patients are in the hematology laboratory, evacuation can be simulated, rather than evacuating actual patients. The entire evacuation route should be walked to verify the exit routes and clearance of the corridors. A summary of the laboratory’s fire response plan can be copied onto a quick reference card and attached to workers’ identification badges to be readily available in a fire situation.

8. Written storage requirements for any flammable or combustible chemicals stored in the laboratory. Chemicals should be arranged according to hazard class and not alphabetically.

9. A well-organized fire safety training program. This program should be completed by all employees. Activities that require walking evacuation routes and locating fire extinguishers and pull boxes in the laboratory area should be scheduled. Types of fires likely to occur and use of the fire extinguisher should be discussed. Local fire departments work with facilities to conduct fire safety programs.

Chemical Hazards

General principles that should be followed in working with chemicals are as follows:

1. Label all chemicals properly, including chemicals in secondary containers, with the name and concentration of the chemical, preparation or fill date, expiration date (time, if applicable), initials of preparer (if done in-house), and chemical hazards (e.g., poisonous, corrosive, flammable). Do not use a chemical that is not properly labeled as to identity or content.

2. Follow all handling and storage requirements for the chemical.

3. Store alcohol and other flammable chemicals in approved safety cans or storage cabinets at least 5 feet away from a heat source (e.g., Bunsen burners, paraffin baths). Limit the quantity of flammable chemicals stored on the workbench to 2 working days’ supply. Do not store chemicals in a hood or in any area where they could react with other chemicals.

4. Use adequate ventilation, such as fume hoods, when working with hazardous chemicals.

5. Use personal protective equipment, such as gloves (e.g., nitrile, polyvinyl chloride, rubber—as appropriate for the chemical in use), rubber aprons, and face shields. Safety showers and eye wash stations should be available every 100 feet or within 10 seconds of travel distance from every work area where the hazardous chemicals are used.

6. Use bottle carriers for glass bottles containing more than 500 mL of hazardous chemical.

7. Use alcohol-based solvents, rather than xylene or other particularly hazardous substances, to clean microscope objectives.

8. The wearing of contact lenses should not be permitted when an employee is working with xylene, acetone, alcohols, formaldehyde, and other solvents. Many lenses are permeable to chemical fumes. Contact lenses can make it difficult to wash the eyes adequately in the event of a splash.

9. Spill response procedures should be included in the chemical safety procedures, and all employees must receive training in these procedures. Absorbent material should be available for spill response. Multiple spill response kits and absorbent material should be stored in various areas and rooms rather than only in the area where they are likely to be needed. This prevents the need to walk through the spilled chemical to obtain the kit.

10. Material safety data sheets (MSDSs) are written by the manufacturers of chemicals to provide information on the chemicals that cannot be put on a label. When an MSDS is received in the laboratory, it must be retained and reviewed with laboratory personnel. The MSDS provides information on the following:

a. Manufacturer—name, address, emergency phone number, date prepared

b. Hazardous ingredients—common names, worker exposure limits

c. Physical and chemical characteristics—boiling point, vapor pressure, evaporation rate, appearance, and odor under normal conditions

d. Physical hazards—data on fire and explosion hazard and ways to handle the hazards

e. Reactivity—stability of the chemical and with what chemicals it will react

f. Health hazards—signs and symptoms of exposure, such as eye irritation, nausea, dizziness, and headache

g. Documentation on the MSDS of whether the reagent or a component of the reagent is considered a carcinogen, teratogen, or mutagen, so that process and procedures are adopted to limit risk of exposure

h. Precautions for safe handling and use—what to do if the chemical spills, how to dispose of the chemical, and what equipment is required for cleanup

i. Control measures—how to reduce the exposure to the chemical and protective clothing or equipment, such as respirator, gloves, and eye protection, that should be used in handling the chemical. See Appendix A for a sample MSDS. Use this sample to review the information that can be found on the MSDS.

Electrical Hazard

1. Equipment must be grounded or double insulated. (Grounded equipment has a three-pronged plug.)

2. Use of “cheater” adapters (adapters that allow three-pronged plugs to fit into a two-pronged outlet) should be prohibited.

3. Use of gang plugs (plugs that allow several cords to be plugged into one outlet) should be prohibited.

4. Use of extension cords should be avoided.

5. Equipment with loose plugs or frayed cords should not be used.

6. Stepping on cords, rolling heavy equipment over cords, and other abuse of cords should be prohibited.

7. When cords are unplugged, the plug, not the cord, should be pulled.

8. Equipment that causes shock or a tingling sensation should be turned off, the instrument unplugged and identified as defective, and the problem reported.

9. Before repair or adjustment of electrical equipment is attempted, the following should be done:

Needle Puncture

Needle puncture is a serious occupational hazard for laboratory workers. Needle-handling procedures should be written and followed, with special attention to phlebotomy procedures and disposal of contaminated needles (see Chapter 3). Other items that can cause a puncture similar to a needle puncture include sedimentation rate tubes, applicator sticks, capillary tubes, glass slides, and transfer pipettes.

Developing a Safety Management Program

Planning Stage: Hazard Assessment and Regulatory Review

Assessment of the hazards found in the laboratory and awareness of the standards and regulations that govern laboratories is a required step in the development of a safety program. Taking the time to become knowledgeable about the regulations and standards that relate to the procedures performed in the hematology laboratory is an essential first step. Examples of the regulatory agencies that have standards, requirements, and guidelines that are applicable to hematology laboratories are given in Box 2-1. Sorting through the regulatory maze can be frustrating, but the government agencies and voluntary standards organizations are willing to assist employers in complying with their standards.

Safety Program Elements

A proactive program should include the following elements:

• Written safety plan—written policies and procedures that explain the steps to be taken for all of the occupational and environmental hazards that exist in the hematology laboratory.

• Training programs—conducted annually for all employees. New employees should receive safety information on the first day that they are assigned to the hematology laboratory.

• Job safety analysis—identifies all of the tasks performed in the hematology laboratory, the steps involved in performing the procedures, and the risk associated with the procedures.

• Safety awareness program—promotes a team approach and encourages employees to take an active part in the safety program.

• Risk assessment—proactive risk (identification) assessment of all the potential safety, occupational, or environmental hazards that exist in the laboratory. The assessment should be conducted at least annually and when a new risk is added to the laboratory. After the risk assessment is conducted, goals, policies, and procedures should be developed to prevent the hazard from injuring a laboratory worker. Some common risks are exposure to bloodborne pathogens; exposure to chemicals; needle punctures; slips, trips, and falls; and ergonomics issues.

• Safety audits and follow-up—a safety checklist should be developed for the hematology laboratory.

• Reporting and investigating of all accidents, “near misses,” or unsafe conditions—the causes of all incidents should be reviewed and corrective action taken, if necessary.

• Emergency drill and evaluation—periodic drills for all potential internal and external disasters. Drills should address the potential accident or disaster before it occurs and test the preparedness of the hematology workers for an emergency situation. Planning for the accident and practicing the response to the accident reduces the panic that results when the correct response is not followed.

• Emergency management plan—emergencies, sometimes called disasters (anything that prevents normal operation of the laboratory), do not occur only in the hospital-based laboratories. Freestanding laboratories, physician office laboratories, and university laboratories can be affected by emergencies that occur in the building or in the community. Emergency planning is crucial to being able to experience an emergency situation and recover enough to continue the daily operation of the laboratory. In addition to the safety risk assessment, a hazard vulnerability analysis should be conducted. Hazard vulnerability analysis helps to identify all of the potential emergencies that may have an impact on the laboratory. Emergencies such as a utility failure—loss of power, water, or telephones—can have a great impact on the laboratory’s ability to perform procedures. Emergencies in the community, such as a terrorist attack, plane crash, severe weather, flood, or civil disturbances, can affect the laboratory workers’ ability to get to work and can affect transportation of crucial supplies or equipment. When the potential emergencies are identified, policies and procedures should be developed and practiced so that the laboratory worker knows the backup procedures and can implement them quickly during an emergency or disaster situation. The emergency management plan should cover the four phases of response to an emergency, as follows:

1. Mitigation—measures to reduce the adverse effects of the emergency

2. Preparedness—design of procedures, identification of resources that may be used, and training in the procedures

3. Response—actions that will be taken when responding to the emergency

4. Recovery—procedures to assess damage, evaluate response, and replenish supplies so that the laboratory can return to normal operation

An example of an emergency management plan is shown in Box 2-2. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute document “Planning for Challenges to Clinical Laboratory Operations During a Disaster” describes detailed actions to prepare for an emergency or disaster. The document also lists some valuable websites for additional resources.3

• Safety committee/department safety meetings—to communicate safety policies to the employees.

• Review of equipment and supplies purchased for the laboratory—for code compliance and safety features.

• Annual evaluation of the safety program—review of goals and performance as well as a review of the regulations to assess compliance in the laboratory.

Summary

• The responsibility of a medical laboratory professional is to perform analytic procedures accurately, precisely, and safely.

• Safe practices must be incorporated into all laboratory procedures and should be followed by every employee.

• The laboratory must adopt standard precautions, which require that all human blood, body fluids, and unfixed tissues be treated as if they were infectious.

• One of the most important safety practices is handwashing.

• Occupational hazards in the laboratory include fire, chemical, and electrical hazards and needle puncture.

• Some common-sense rules of safety are as follows:

• Be knowledgeable about the procedures being performed. If in doubt, ask for further instructions.

• Wear protective clothing and use protective equipment when required.

• Clean up spills immediately, if substance is low hazard and spill is small; otherwise contact hazardous materials team (internal or vendor) for spill reporting and appropriate spill management.

• Keep workstations clean and corridors free from obstruction.

• Report injuries and unsafe conditions. Review accidents and incidents to determine their fundamental cause. Take corrective action to prevent further injuries.

Review Questions

1. Standard precautions apply to all of the following except:

2. The most important practice in preventing the spread of disease is:

a. Wearing masks during patient contact

c. Wearing disposable laboratory coats

d. Identifying specimens from known or suspected HIV- and HBV-infected patients with a red label

3. The appropriate dilution of bleach to be used in laboratory disinfection is:

4. How frequently should fire alarms and sprinkler systems be tested?

5. Where should alcohol and other flammable chemicals be stored?

a. In an approved safety can or storage cabinet away from heat sources

b. Under a hood and arranged alphabetically for ease of identification in an emergency

c. In a refrigerator at 2° C to 8° C to reduce volatilization

6. The most frequent cause of needle punctures is:

a. Patient movement during venipuncture

b. Improper disposal of phlebotomy equipment

c. Inattention during removal of needle after venipuncture

d. Failure to attach needle firmly to syringe or tube holder

7. Under which of the following circumstances would an MSDS be helpful?

a. A phlebotomist has experienced a needle puncture with a clean needle.

b. A fire extinguisher failed during routine testing.

c. A pregnant laboratory staff member has asked whether she needs to be concerned about working with a given reagent.

d. During a safety inspection, an aged microscope power supply is found to have a frayed power cord.

8. It is a busy evening in the City Hospital hematology department. One staff member called in sick, and there was a major auto accident that has one staff member tied up in the blood bank all evening. Mary, the medical laboratory scientist covering hematology, is in a hurry to get a stat sample on the analyzer but needs to pour off an aliquot for another department. She is wearing gloves and a gown. She carefully covers the stopper of the well-mixed ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube with a gauze square and tilts the stopper toward her so it opens away from her. She pours off about 1 mL into a prelabeled tube, replaces the stopper of the EDTA tube, and puts it in the sample rack and sets it on the conveyor. She then runs the poured sample off to the other department. How would you assess Mary’s safety practice?

a. Mary was careful and followed all appropriate procedures.

b. Mary should have used a shield when opening the tube.

c. Mary should have poured the sample into a sterile tube.

d. Mary should have wiped the tube with alcohol after replacing the stopper.

9. A class C fire extinguisher would be appropriate to use on a fire in a chemical cabinet.

10. According to OSHA standards, laboratory coats must be all of the following except:

cups of bleach to 1 gallon of water to achieve the recommended concentration of chlorine of 5500 ppm. Because this solution is not stable, it must be made fresh daily. The container of 1 : 10 solution of bleach should be labeled properly with the name of the solution, the date and time prepared, the date and time of expiration (24 hours), and the initials of the preparer. Bleach is not recommended for aluminum surfaces. Other solutions used to decontaminate include, but are not limited to a phenol-based disinfectant such as Amphyl, tuberculocidal disinfectants, and 70% ethanol. All paper towels used in the decontamination process should be disposed of as biohazardous waste. Documentation of the disinfection of work areas and equipment after each shift is required.

cups of bleach to 1 gallon of water to achieve the recommended concentration of chlorine of 5500 ppm. Because this solution is not stable, it must be made fresh daily. The container of 1 : 10 solution of bleach should be labeled properly with the name of the solution, the date and time prepared, the date and time of expiration (24 hours), and the initials of the preparer. Bleach is not recommended for aluminum surfaces. Other solutions used to decontaminate include, but are not limited to a phenol-based disinfectant such as Amphyl, tuberculocidal disinfectants, and 70% ethanol. All paper towels used in the decontamination process should be disposed of as biohazardous waste. Documentation of the disinfection of work areas and equipment after each shift is required.