Rickettsial and mycoplasma infections

RICKETTSIAE

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC FEATURES

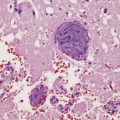

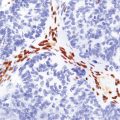

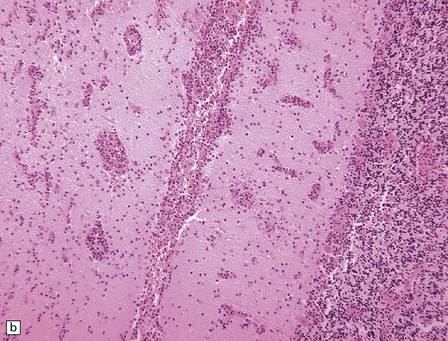

Most of the scanty published data relate to typhus and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. In fatal cases the brain is swollen and contains petechial hemorrhages (Fig. 14.2). Histology reveals angiocentric inflammation, thrombosis, and microinfarcts, in the absence of fibrinoid necrosis. Microglial nodules are usually detected in the gray matter. Rickettsiae can be demonstrated by immunofluorescence or, less consistently, by tinctorial methods (Fig. 14.3); Brown and Hopps modified Gram stain is most sensitive. There may be a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate with a variable amount of hemorrhage in the leptomeninges.

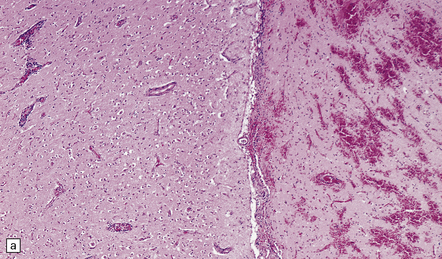

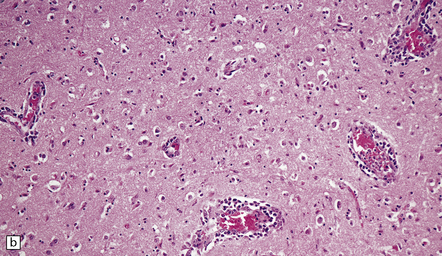

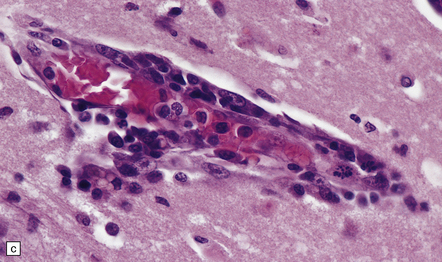

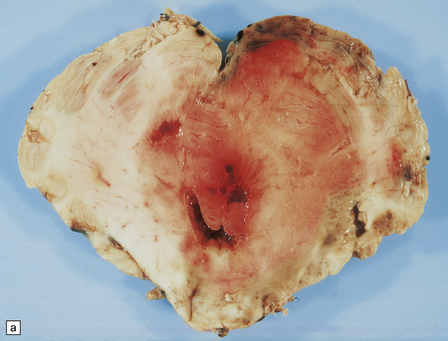

14.2 Rocky Mountain spotted fever in a dog.

(a) Section through part of two adjacent gyri. The gyrus on the right shows hemorrhagic necrosis. There is mild inflammation in the meninges and mononuclear cell cuffing of blood vessels in the cortex of the left gyrus. (b) Cuffing of blood vessels by mononuclear inflammatory cells. (c) At higher magnification, the inflammatory infiltrate is seen to comprise a mixture of lymphocytes and macrophages. Note the absence of neutrophils or of fibrinoid necrosis. (All prepared from material provided by Bruce H Williams, MAJ, VC, USA, Department of Veterinary Pathology, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington DC, USA.)

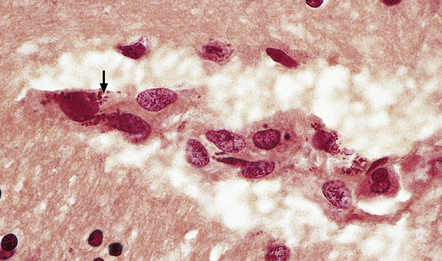

14.3 Human Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Inflammation in the brain was minimal. Gram-negative coccobacilli (arrow) are, however, visible at high magnification, in the cytoplasm of endothelial cells. (Prepared from material provided by Dr Robert V. Jones, COL, MC, USAR, Department of Pathology, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington DC, USA.)

MYCOPLASMA

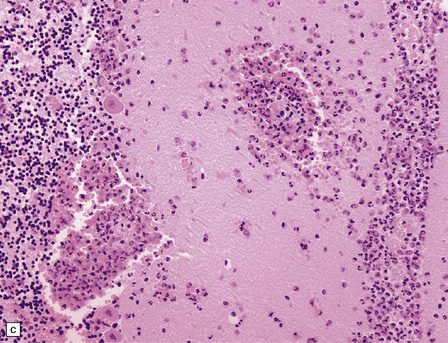

M. pneumoniae is one of several species of bacteria in the genus Mycoplasma that lack a cell wall. They cannot be stained by Gram’s method and are resistant to antibiotics such as β-lactams, which target the bacterial wall. M. pneumoniae is recognized as a rare cause of neurologic disease, usually in children. Autopsy studies are very few. CNS complications of Mycoplasma infection are estimated to occur in 1 per 1000 cases (of systemic infection) and include encephalitis (often with evidence of cerebellar involvement), brain infarction, aseptic meningitis, polyradiculitis, and myelitis. Attribution of meningitis or encephalitis to Mycoplasma is usually on the basis of serologic studies (with high complement fixing antibody titres) rather than by direct isolation of the microorganism from CSF or brain tissue. However, PCR is used increasingly to detect M. pneumoniae sequences, including in CSF. The pathogenesis of the varied CNS manifestations of M. pneumoniae infection is still debated, with evidence from different studies of various combinations of immune complex deposition, thrombosis of microvessels, autoimmune processes, neurotoxin production, or direct infection of the CNS. In a rare autopsy case (Fig. 14.4), M. pneumoniae infection was complicated by severe widespread necrotizing meningoencephalitis, and erythrophagocytosis within leptomeninges and spleen.

14.4 Hemophagocytic syndrome complicating Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in a 12-year-old boy.

(a) The cerebellum shows asymmetric swelling and dusky brown discoloration, and includes foci of hemorrhage. (b) Inflammatory exudate in the leptomeninges and extending along Virchow–Robin spaces into the cerebellar cortex. Inflammatory cells are also scattered throughout much of the molecular layer in this field. (c) Higher magnification view of perivascular and parenchymal inflammatory infiltrates in the molecular and Purkinje cell layers. Neutrophils predominate, but there are also other large cells with indented nuclei; some of these cells contain erythrocytes within their cytoplasm. (Material kindly provided by Dr Waney Squier, Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, England. For details of case see Bruch et al, 2001.)

REFERENCES

Balraj, P., Renesto, P., Raoult, D. Advances in rickettsia pathogenicity. Ann N Y Acad Sci.. 2009;1166:94–105.

Bechah, Y., Capo, C., Grau, G., et al. Rickettsia prowazekii infection of endothelial cells increases leukocyte adhesion through αvβ3 integrin engagement. Clin Microbiol Infect.. 2009;15:S249–S250.

Brouqui, P., Parola, P., Fournier, P.E., et al. Spotted fever rickettsioses in southern and eastern Europe. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol.. 2007;49:2–12.

Fournier, P.E., Raoult, D. Current knowledge on phylogeny and taxonomy of Rickettsia spp. Ann N Y Acad Sci.. 2009;1166:1–11.

Mansueto, P., Vitale, G., Cascio, A., et al. New insight into immunity and immunopathology of Rickettsial diseases. Clin Dev Immunol.. 2012;2012:967852.

Parola, P., Davoust, B., Raoult, D. Tick- and flea-borne rickettsial emerging zoonoses. Vet Res.. 2005;36:469–492.

Walker, D.H. Rickettsiae and rickettsial infections: the current state of knowledge. Clin Infect Dis.. 2007;45:S39–S44.

Walker, D.H., Paddock, C.D., Dumler, J.S. Emerging and re-emerging tick-transmitted rickettsial and ehrlichial infections. Med Clin North Am.. 2008;92:1345–1361.

Walker, D.H., Valbuena, G.A., Olano, J.P. Pathogenic mechanisms of diseases caused by Rickettsia. Ann N Y Acad Sci.. 2003;990:1–11.

Bruch, L.A., Jefferson, R.J., Pike, M.G., et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection, meningoencephalitis, and hemophagocytosis. Pediatr Neurol.. 2001;25:67–70.

Daxboeck, F. Mycoplasma pneumoniae central nervous system infections. Curr Opin Neurol.. 2006;19:374–378.

Domenech, C., Leveque, N., Lina, B., et al. Role of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in pediatric encephalitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis.. 2009;28:91–94.

Guleria, R., Nisar, N., Chawla, T.C., et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and central nervous system complications: a review. J Lab Clin Med.. 2005;146:55–63.

Rhodes, R.H., Monastersky, B.T., Tyagi, R., et al. Mycoplasmal cerebral vasculopathy in a lymphoma patient: presumptive evidence of Mycoplasma pneumoniae microvascular endothelial cell invasion in a brain biopsy. J Neurol Sci.. 2011;309:18–25.

Tsiodras, S., Kelesidis, I., Kelesidis, T., et al. Central nervous system manifestations of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. J Infect.. 2005;51:343–354.

Yis, U., Kurul, S.H., Cakmakci, H., et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: nervous system complications in childhood and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr.. 2008;167:973–978.