Chronic bacterial infections and neurosarcoidosis

TUBERCULOSIS

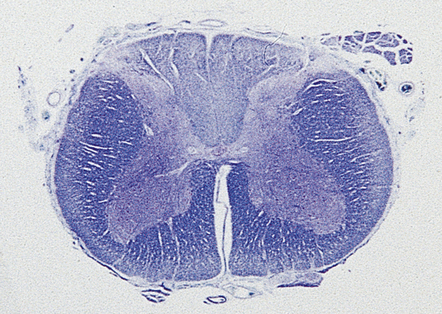

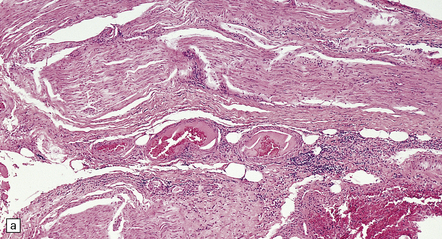

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

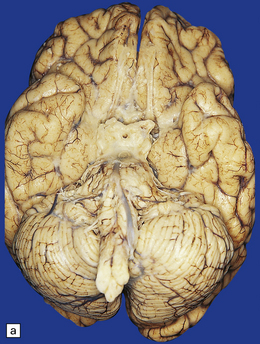

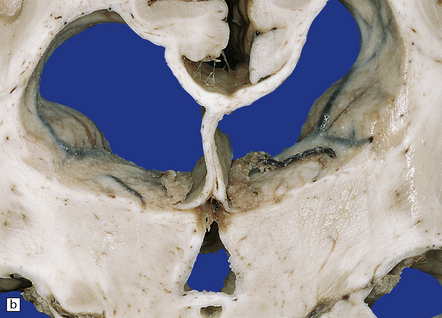

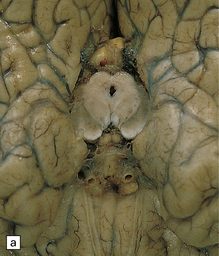

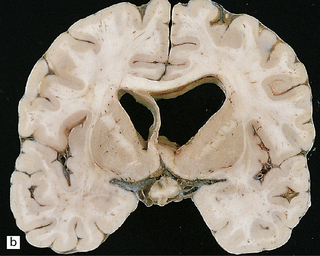

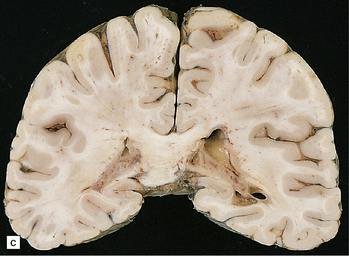

Tuberculous meningitis is characterized by a gelatinous subarachnoid exudate. This may appear slightly nodular and is usually thickest in the sylvian fissures, over the base of the brain (Fig. 16.1a), and around the spinal cord. Sectioning of the brain usually reveals a similar exudate within the choroid plexus and lining the ventricles. Tubercles may be visible in the meninges, usually adjacent to sulcal veins, and in the ventricular lining (Fig. 16.1b). Small superficial tuberculomas are quite common (Fig. 16.2) and may be associated with an overlying meningeal exudate. Large tuberculomas occasionally occur, but are rare in patients with meningitis.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

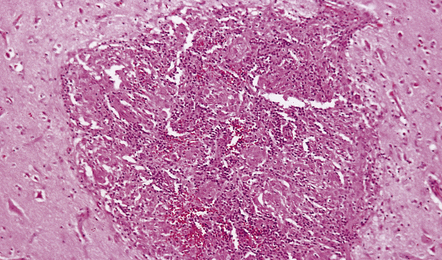

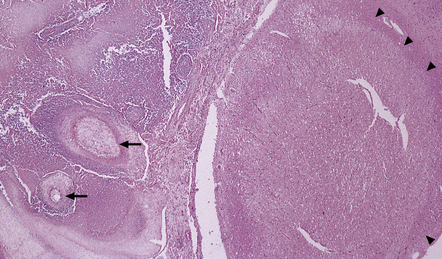

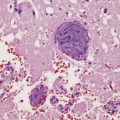

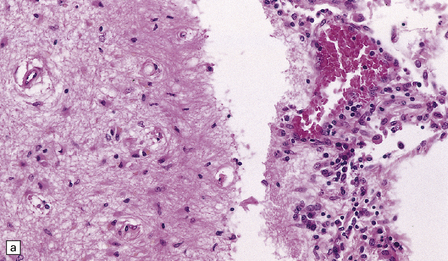

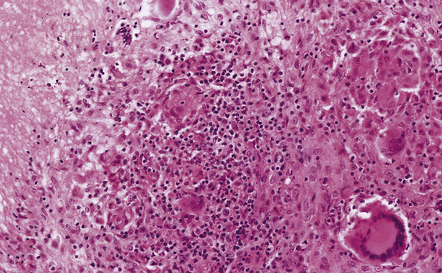

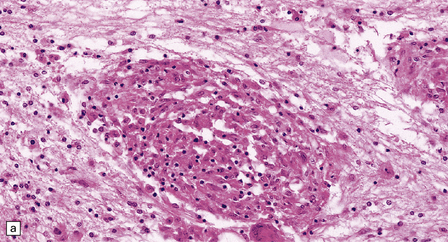

The meningeal and ventricular exudate contains lymphocytes, macrophages, and sparse plasma cells, admixed with necrotic material and fibrin (Fig. 16.3a). There may be accumulations of epithelioid cells and fibroblasts, multinucleated giant cells, and well-defined tuberculous granulomas (Figs 16.2, 16.3, 16.4) with central caseous necrosis.

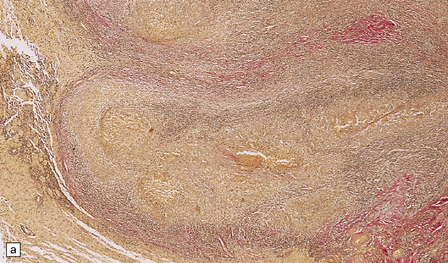

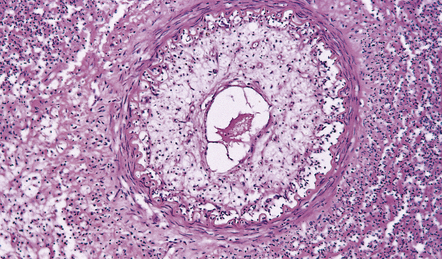

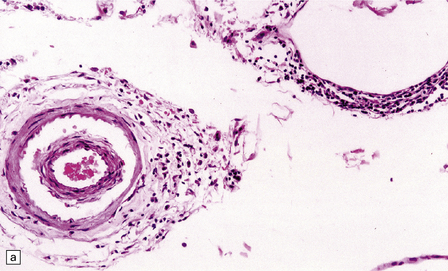

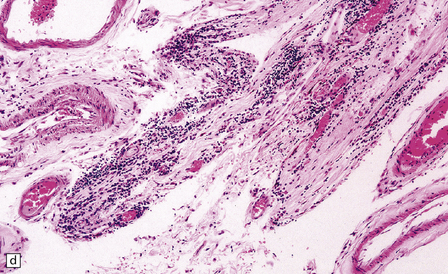

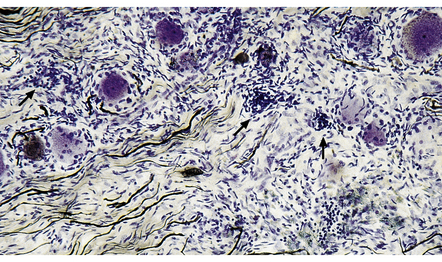

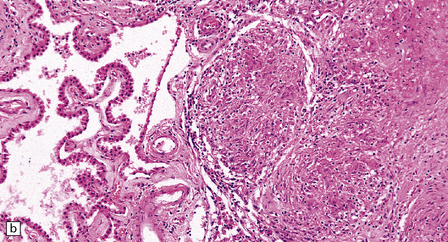

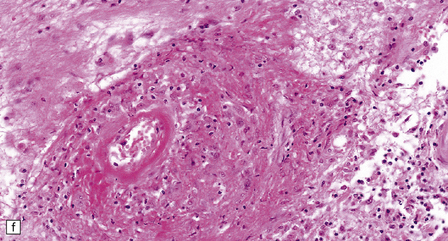

16.3 Histology of tuberculous meningitis.

(a) There is a meningeal exudate of macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fibrin. The superficial cortex (at left) is densely gliotic. (b) Meningeal artery surrounded by lymphocytes, macrophages, and an occasional multinucleated giant cell. There is mild endarteritis, with proliferation of subintimal fibroblasts.

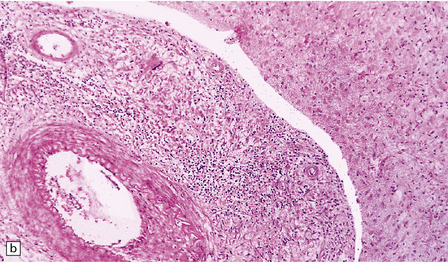

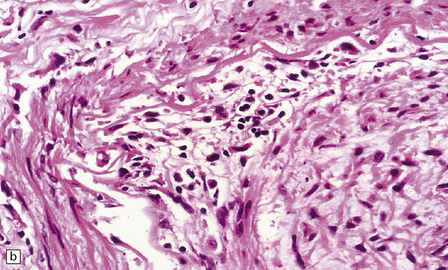

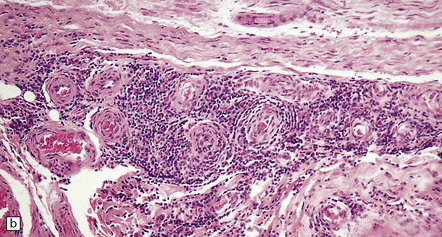

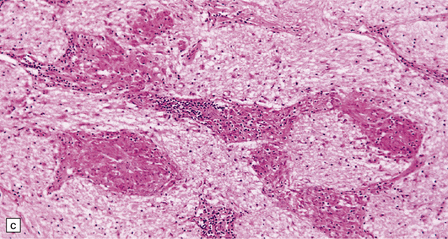

16.4 Part of a caseating meningeal granuloma in tuberculous meningitis.

There is a characteristic infiltrate of lymphocytes, epithelioid macrophages, and Langhans’-type multinucleated giant cells.

Mycobacteria may be readily demonstrable or very sparse. Silver impregnation reveals a loss of reticulin in the caseous material (see

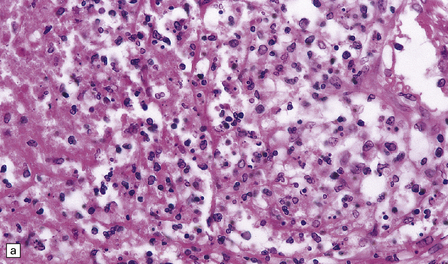

Fig. 16.9 b). In immunosuppressed patients the mycobacteria are usually numerous and the inflammation less granulomatous and usually lacking multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 16.5). Parenchymal arteritis and infarcts have been reported as frequent findings in patients with AIDS.

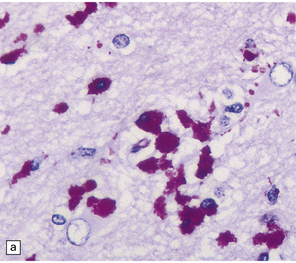

16.5 Tuberculous meningitis in an immunosuppressed patient.

(a) Inflammation in the leptomeninges of a patient with AIDS. Note the absence of a typical granulomatous tissue reaction. (b) Numerous acid-fast bacilli in AIDS-associated tuberculous meningitis.

The inflammation extends into the subpial and periventricular brain tissue, which shows reactive astrocytosis (Fig. 16.3a) and microglial proliferation. This may be associated with degeneration of white matter adjacent to the ventricles and in the spinal cord.

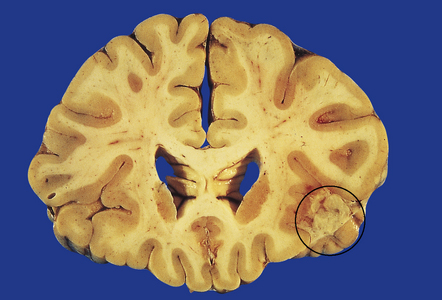

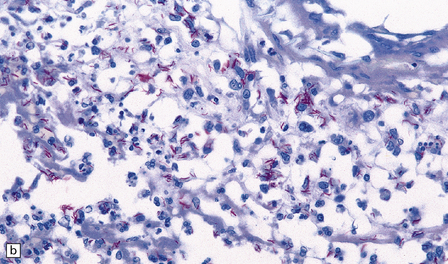

The inflammatory cells tend to infiltrate through the adventitia, into the media and even the intima, of blood vessels within the exudate (Figs 16.3b, 16.6). Thrombosis occurs in some blood vessels. In others, the inflammation provokes a subintimal intimal fibroblastic reaction that narrows and can occlude the lumen (Figs 16.3b, 16.7). Infarcts are therefore common (Fig. 16.8), particularly in the superficial cortex and, due to the involvement of perforating branches of the middle cerebral artery, in the basal ganglia.

16.6 Mild tuberculous endarteritis.

Extension of granulomatous inflammation through the adventitia and media of a meningeal artery.

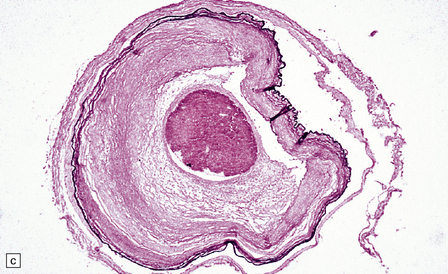

16.7 Tuberculous endarteritis.

Narrowing of the lumen of an inflamed meningeal artery by accumulation of chronic inflammatory cells and proliferation of intimal connective tissue.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Histology reveals solitary or confluent tuberculous granulomas with central caseous necrosis surrounded by lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, Langhans’-type multinucleated giant cells, and an outer zone of collagen, fibroblasts, lymphocytes, and macrophages (Fig. 16.9). Older lesions may calcify. The adjacent parenchyma is usually markedly gliotic.

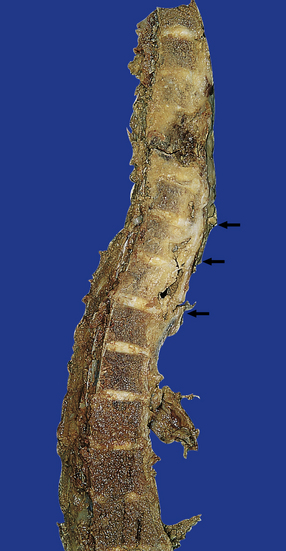

SPINAL EPIDURAL TUBERCULOSIS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

There is usually extensive destruction, which may be associated with collapse of the affected vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs. This is associated with variable protrusion of gray multinodular granulomatous tissue into the epidural space (Fig. 16.10).

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The epidural mass shows typical granulomatous tuberculous inflammation with caseation. Changes in the spinal cord reflect a combination of focal compression by epidural inflammatory tissue or vertebral kyphosis, ischemia (see Chapter 9), and secondary long tract degeneration. Compression of the anterior spinal artery may produce a typical ‘watershed’ infarct (see Chapter 9) involving the upper and middle parts of the thoracic cord.

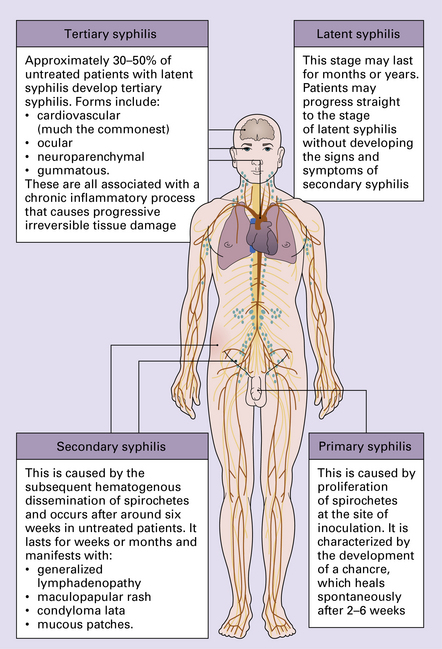

SYPHILIS

MENINGOVASCULAR SYPHILIS

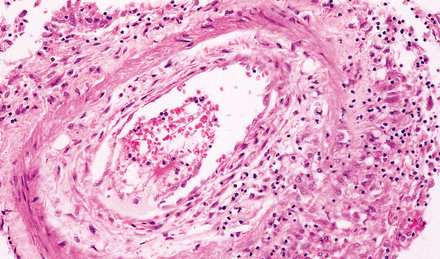

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The meninges contain scattered lymphocytes and plasma cells. The gummas, if present, resemble tubercles, but the central (gummatous) necrosis differs histologically because the reticulin is preserved. The arteritis can involve large, medium-sized, or small arteries and arterioles. It is characterized histologically by lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration of the adventitia and media, and concentric collagenous thickening of the intima, which eventually occludes the lumen (Fig. 16.12). A chronic inflammatory infiltrate may also surround and infiltrate leptomeningeal veins, and cranial nerves. The brain and spinal parenchyma often includes foci of ischemic scarring or frank infarction, and the periventricular white matter may show perivascular inflammation and gliosis (Fig. 16.12).

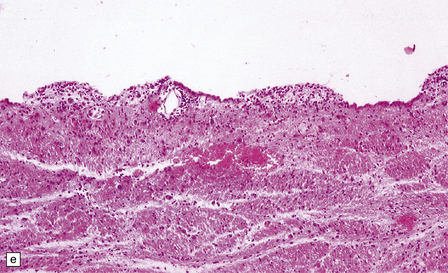

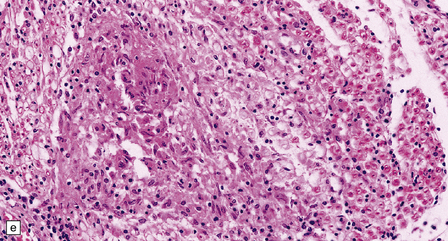

16.12 Meningovascular syphilis.

(a) A lymphocytic infiltrate is present in the adventitia of leptomeningeal veins and arteries. (b) Chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the fibrotic, thickened media and intima of a meningeal artery. (c) Marked collagenous intimal thickening in end-stage syphilitic arteritis involving the middle cerebral artery. (d) Inflammatory infiltrate within oculomotor nerve. (e) Perventricular inflammation and gliosis.

GENERAL PARESIS (OF THE INSANE)

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APEARANCE

The meninges are thickened and fibrotic and the underlying brain is firm and atrophic. Histology reveals scanty meningeal and perivascular parenchymal aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells, moderate loss of neurons from the cerebral cortex, reactive gliosis, and striking proliferation of rod-shaped microglia (Fig. 16.13). Spirochetes are demonstrable in the cortex by silver impregnation in a minority of cases.

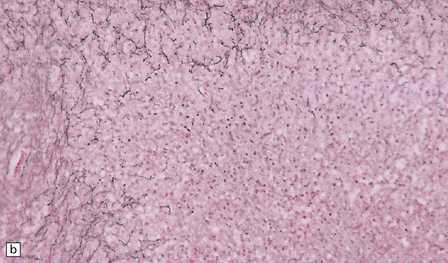

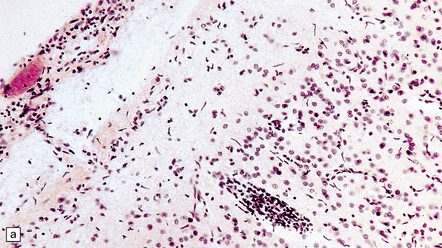

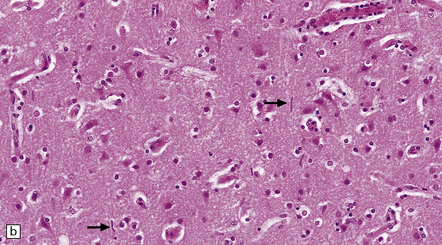

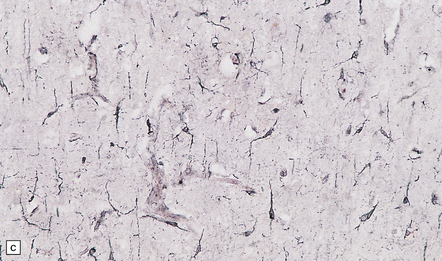

16.13 Histology of general paresis.

(a) Scanty meningeal and perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes in syphilitic general paresis. Scattered elongated nuclei or rod-shaped microglia are visible in the cortex. (b) The rod-shaped microglia (arrows) are relatively inconspicuous in conventional histologic preparations. (c) The microglia are well demonstrated by silver carbonate impregnation. (Figures (a) and (b) are from material generously provided from the Corsellis collection, West London Mental Health Trust.)

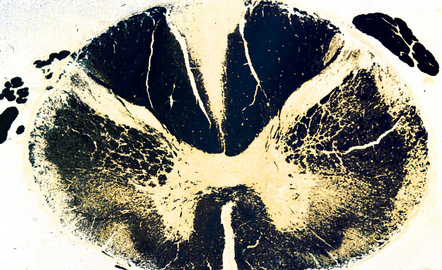

TABES DORSALIS

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

By the time that patients come to necropsy, the degree of inflammation is often quite mild, with scattered lymphocytes and plasma cells in the fibrotic spinal leptomeninges and dorsal root ganglia (Fig. 16.14). There is moderate to marked loss of neurons from the dorsal root ganglia, with associated proliferation of satellite cells (forming nodules of Nageotte), depletion of dorsal root fibers (this may appear histologically unimpressive), and posterior column degeneration (Figs 16.15, 16.16). The changes are usually most marked in the lumbar region of the cord.

16.14 Tabes dorsalis.

A lymphocytic infiltrate is present in this dorsal root ganglion. Nodules of Nageotte (arrows) are seen where ganglion cells have degenerated.

GUMMATOUS NEUROSYPHILIS

Gummas are a late manifestation of tertiary syphilis and only rarely involve the CNS as solitary space-occupying lesions (Fig. 16.17). As noted above, they resemble tuberculomas, but in gummatous necrosis the reticulin is usually preserved.

LYME NEUROBORRELIOSIS

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Perivascular inflammation and, in chronic disease, axonal degeneration, have been noted in peripheral nerve biopsies (Fig. 16.18).

16.18 Peripheral nerve involvement in Lyme disease.

(a,b) This patient had acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, a chronic cutaneous disorder associated with Lyme borreliosis. Note the mononuclear cell infiltration of the epineurium which is accentuated in perivascular regions; both photomicrographs are from the same specimen. (Courtesy of Professor H. Budka, University of Vienna, Austria.)

NEUROSARCOIDOSIS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The distribution of lesions is variable. There is often yellowish-gray thickening of the leptomeninges over the base of the brain, particularly around the infundibular stalk and optic chiasm (Fig. 16.19). The meninges covering the brain stem, cerebellum and, less commonly, the cerebral convexities, may also show macroscopic involvement, as may those around the spinal cord and nerve roots. In some cases, sectioning of the brain reveals gelatinous gray material in the walls of the ventricles and in the choroid plexus. This may be associated with obstructive hydrocephalus.

16.19 Neurosarcoidosis – macroscopic appearances.

(a) Thickening of the leptomeninges over the floor of the hypothalamus and around the optic chiasm. (b) The optic chiasm is encased in gelatinous gray tissue. The ventricles are asymmetrically dilated, and lined by gelatinous material. (c) Gelatinous gray material is present in the choroid plexus and in the walls of the ventricles.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Histology reveals granulomatous inflammation in the meninges, ventricles, and adjacent brain or cord parenchyma (Fig. 16.20). Although the granulomas are classically noncaseating, they may show central fibrosis and, rarely, necrosis. The floor of the hypothalamus and the infundibulum are often extensively involved. There may be large granulomatous masses in the choroid plexus. The inflammatory infiltrate can involve the optic nerves and chiasm, the facial, auditory, vestibular, and other cranial nerves, and the spinal nerve roots. Small veins and arteries may be incorporated within the granulomas. Rarely, this leads to fibrinoid necrosis and even thrombosis.

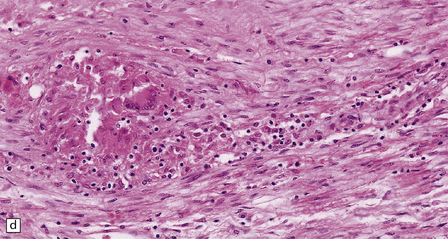

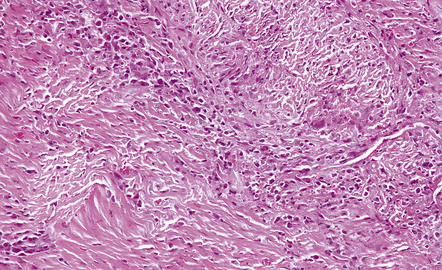

16.20 Neurosarcoidosis – microscopic appearances.

(a) Noncaseating sarcoid granuloma in the hypothalamus. (b) Sarcoid granulomas in choroid plexus. (c) Granulomatous infiltrate within the optic nerve. (d) Oculomotor nerve containing sarcoid granuloma. (e) Granulomatous infiltration of spinal nerve roots. (f) Fibrinoid necrosis of small artery within a sarcoid granuloma.

IDIOPATHIC HYPERTROPHIC PACHYMENINGITIS

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The affected dura is thickened and may have a slightly nodular appearance. Microscopy reveals collagenous thickening and patchy infiltrations by a polymorphic infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages and occasional multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 16.21). Eosinophils may also be present. Granulomas and necrosis have been reported in a few cases. The diagnosis depends on excluding, as far as possible, tuberculosis, syphilis and fungal infections, lymphoma or other neoplasms, Wegener’s arteritis, rheumatoid arthritis and other systemic connective tissue/autoimmune disorders.

16.21 Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis.

The patient presented with headaches and lower cranial nerve palsies. He initially improved on steroids and azathioprine but subsequently slowly deteriorated, over several years. The dura is markedly thickened and infiltrated by a mixture of lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells and an occasional giant cell.

WHIPPLE’S DISEASE

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

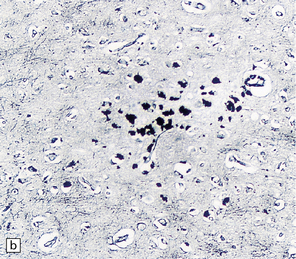

Foci of granular yellow or gray discoloration may be macroscopically discernible in the thalamus, hypothalamus, cerebellar dentate nuclei, and around the aqueduct. Microscopy reveals meningeal and parenchymal clusters of macrophages containing PAS-positive, diastase-resistant material (Fig. 16.22). The bacilli are Gram-positive, but this may be difficult to demonstrate because of degenerative changes. They can be demonstrated reasonably well by methenamine silver impregnation. There is usually a scanty lymphocytic infiltrate. Thickening and fibrosis of the walls of arteries and arterioles in affected parts of the brain may lead to the development of small infarcts.

16.22 Cerebral Whipple’s disease.

(a) A cluster of macrophages containing PAS-positive, diastase-resistant cytoplasmic material. (b) The bacilli are demonstrable by methenamine silver impregnation. (c) Electron microscopy reveals the intracellular bacilli. (Courtesy of Dr A F Cabello, Madrid.)

Electron microscopy reveals rod-shaped intracellular bacilli (Fig. 16.22), many of which may be degenerating, as well as accumulations of membranous material.

REFERENCES

Anuradha, H.K., Garg, R.K., Sinha, M.K., et al. Intracranial tuberculomas in patients with tuberculous meningitis: predictors and prognostic significance. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis.. 2011;15:234–239.

Be, N.A., Kim, K.S., Bishai, W.R., et al. Pathogenesis of central nervous system tuberculosis. Curr Mol Med.. 2009;9:94–99.

Christensen, A.S., Andersen, A.B., Thomsen, V.O., et al. Tuberculous meningitis in Denmark: a review of 50 cases. BMC Infect Dis.. 2011;11:47.

Dastur, D.K., Manghani, D.K., Udani, P.M. Pathology and pathogenetic mechanisms in neurotuberculosis. Radiol Clin North Am.. 1995;33:733–752.

Garg, R.K., Sharma, R., Kar, A.M., et al. Neurological complications of miliary tuberculosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg.. 2010;112:188–192.

Garg, R.K., Sinha, M.K. Tuberculous meningitis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Neurol.. 2011;258:3–13.

Katrak, S.M., Shembalkar, P.K., Bijwe, S.R., et al. The clinical, radiological and pathological profile of tuberculous meningitis in patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Neurol Sci.. 2000;181:118–126.

Man, H., Sellier, P., Boukobza, M., et al. Central nervous system tuberculomas in 23 patients. Scand J Infect Dis.. 2010;42:450–454.

Chahine, L.M., Khoriaty, R.N., Tomford, W.J., et al. The changing face of neurosyphilis. Int J Stroke.. 2011;6:136–143.

Marra, C.M. Neurosyphilis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep.. 2004;4:435–440.

Marra, C.M. Update on neurosyphilis. Curr Infect Dis Rep.. 2009;11:127–134.

Peters, M., Gottschalk, D., Boit, R., et al. Meningovascular neurosyphilis in human immunodeficiency virus infection as a differential diagnosis of focal CNS lesions: a clinicopathological study. J Infect.. 1993;27:57–62.

Zetola, N.M., Klausner, J.D. Syphilis and HIV infection: an update. Clin Infect Dis.. 2007;44:1222–1228.

Bertrand, E., Szpak, G.M., Pilkowska, E., et al. Central nervous system infection caused by Borrelia burgdorferi. Clinico-pathological correlation of three post-mortem cases. Folia Neuropathol.. 1999;37:43–51.

Halperin, J.J. Lyme disease and the peripheral nervous system. Muscle Nerve.. 2003;28:133–143.

Halperin, J.J. Nervous system Lyme disease. J R Coll Physicians Edinb.. 2010;40:248–255.

Meurers, B., Kohlhepp, W., Gold, R., et al. Histopathological findings in the central and peripheral nervous systems in neuroborreliosis. A report of three cases. J Neurol.. 1990;237:113–116.

Miklossy, J., Kasas, S., Zurn, A.D., et al. Persisting atypical and cystic forms of Borrelia burgdorferi and local inflammation in Lyme neuroborreliosis. J Neuroinflammation.. 2008;5:40.

Miklossy, J., Kuntzer, T., Bogousslavsky, J., et al. Meningovascular form of neuroborreliosis: similarities between neuropathological findings in a case of Lyme disease and those occurring in tertiary neurosyphilis. Acta Neuropathol.. 1990;80:568–572.

Pachner, A.R., Steiner, I. Lyme neuroborreliosis: infection, immunity, and inflammation. Lancet Neurol.. 2007;6:544–552.

Topakian, R., Stieglbauer, K., Nussbaumer, K., et al. Cerebral vasculitis and stroke in Lyme neuroborreliosis. Two case reports and review of current knowledge. Cerebrovasc Dis.. 2008;26:455–461.

Joseph, F.G., Scolding, N.J. Neurosarcoidosis: a study of 30 new cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.. 2009;80:297–304.

Nowak, D.A., Widenka, D.C. Neurosarcoidosis: a review of its intracranial manifestation. J Neurol.. 2001;248:363–372.

Pawate, S., Moses, H., Sriram, S. Presentations and outcomes of neurosarcoidosis: a study of 54 cases. QJM.. 2009;102:449–460.

Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis

D’Andrea, G., Trillo, G., Celli, P., et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertrophic pachymeningitis: two case reports and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev.. 2004;27:199–204.

Kupersmith, M.J., Martin, V., Heller, G., et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis. Neurology.. 2004;62:686–694.

Riku, S., Kato, S. Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis. Neuropathology.. 2003;23:335–344.

Gerard, A., Sarrot-Reynauld, F., Liozon, E., et al. Neurologic presentation of Whipple disease: report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore).. 2002;81:443–457.

Louis, E.D., Lynch, T., Kaufmann, P., et al. Diagnostic guidelines in central nervous system Whipple’s disease. Ann Neurol.. 1996;40:561–568.

Lugassy, M.M., Louis, E.D. Neurologic manifestations of Whipple’s disease. Curr Infect Dis Rep.. 2006;8:301–306.

Panegyres, P.K., Edis, R., Beaman, M., et al. Primary Whipple’s disease of the brain: characterization of the clinical syndrome and molecular diagnosis. QJM.. 2006;99:609–623.