Chapter 374 Retropharyngeal Abscess, Lateral Pharyngeal (Parapharyngeal) Abscess, and Peritonsillar Cellulitis/Abscess

Retropharyngeal and Lateral Pharyngeal Abscess

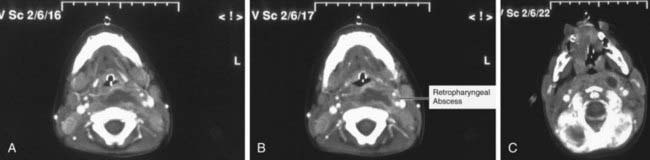

Incision for drainage and culture of an abscessed node provides the definitive diagnosis, but CT can be useful in identifying the presence of a retropharyngeal, lateral pharyngeal, or parapharyngeal abscess (Figs. 374-1 and 374-2). With CT scans, deep neck infections can be accurately identified and localized, but CT accurately identifies abscess formation in only 63% of patients. Soft tissue neck films taken during inspiration with the neck extended might show increased width or an air-fluid level in the retropharyngeal space. CT with contrast medium enhancement can reveal central lucency, ring enhancement, or scalloping of the walls of a lymph node. Scalloping of the abscess wall is thought to be a late finding and predicts abscess formation.

Retropharyngeal and lateral pharyngeal infections are most often polymicrobial; the usual pathogens include group A streptococcus (Chapter 176), oropharyngeal anaerobic bacteria (Chapter 205), and Staphylococcus aureus (Chapter 174.1). Studies have documented an increased incidence of group A streptococcus recovered from such abscesses. Other pathogens can include Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella, and Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare.

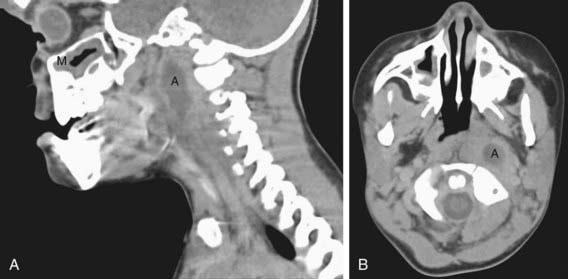

An uncommon but characteristic infection of the parapharyngeal space is Lemierre disease, in which infection from the oropharynx extends to cause septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein and embolic abscesses in the lungs (Fig. 374-3). The causative pathogen is Fusobacterium necrophorum, an anaerobic bacterial constituent of the oropharyngeal flora. The typical presentation is that of a previously healthy adolescent or young adult with a history of recent pharyngitis who becomes acutely ill with fever, hypoxia, tachypnea, and respiratory distress. Chest radiography demonstrates multiple cavitary nodules, often bilateral and often accompanied by pleural effusion. Blood culture may be positive. Treatment involves prolonged intravenous antibiotic therapy with penicillin or cefoxitin; surgical drainage of extrapulmonary metastatic abscesses may be necessary (Chapters 373, 375).

Azimi PH, Grossman M. Irritability and neck stiffness in a five-month-old infant. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:724. 728–729

Blotter JW, Yin L, Glyn M, et al. Otolaryngology consultation for peritonsillar abscess in the pediatric population. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1698-1701.

Coticchia JM, Getnick GS, Yun RD, et al. Age-, site-, and time-specific differences in pediatric deep neck abscesses. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:201-207.

Gavril H, Vaiman M, Kessler A, et al. Microbiology of peritonsillar abscess as an indication for tonsillectomy. Medicine. 2008;87:33-36.

Kirse DJ, Roberson DW. Surgical management of retropharyngeal space infections in children. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1413-1422.

Lee SS, Schwartz RH, Bahadori RS. Retropharyngeal abscess: epiglottitis of the new millennium. J Pediatr. 2001;138:435-437.

Philpott CM, Selvadurai D, Banerjee AR. Paediatric retropharyngeal abscess. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118:919-926.

Plymyer MR, Zoccola DC, Tallarita G. An 18 year old man presenting with sepsis following a recent pharyngeal infection. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:813-814.

Vural C, Gungor A, Comerci S. Accuracy of computerized tomography in deep neck infections in the pediatric population. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24:143-148.

Wright CT, Stocks RSM, Armstrong DL, et al. Pediatric mediastinitis as a complication of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus retropharyngeal abscess. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:408-413.

Zavereo M, Pereira K. Chronic retropharyngeal abscess presenting as obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatr Emer Care. 2008;24:382-384.