4 Psychophysiology and pelvic pain

Psychophysiology in historical perspective

Although scientific advances have helped to clarify some mind–body issues, they are far from being resolved. How can the subjective qualities and the essence of a state of consciousness be explained in naturalistic terms? The most recognized modern form of dualism comes from the writings of René Descartes (1641) (see Marenbon 2007), and holds that the mind is a separate mental substance. Descartes clearly identified the mind with consciousness and self-awareness, and distinguished it from the brain, which he identified with intelligence. He was the first to formulate the mind–body problem in the form that it exists today.

Modern psychophysiological research

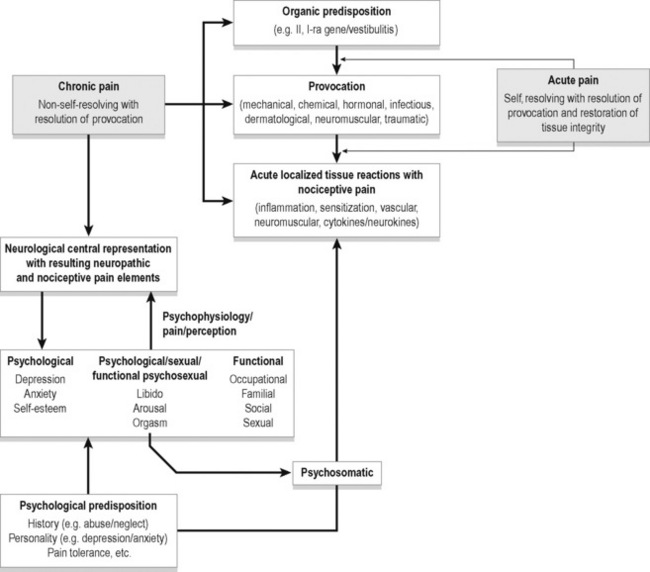

A wide variety of provocative events can lead to localized acute tissue reactions with resulting nociceptive pain. This acute pain most often resolves on resolution of the provocative factors. In the presence of organic and psychological predisposition this pain may become chronic pain with the addition of neuropathic elements to the nociceptive factors. With urogenital pain, psychological, sexual and functional states are adversely affected adding a psychophysiological element to the chronic pain. Figure 4.1 depicts some potential relationships among biological and psychological factors in chronic pelvic pain.

Prostate and pelvic pain

One recent study (Ullrich et al. 2007) of benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) implicated the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and sympathetic nervous system reactivity in prostate enlargement. Eighty-three men with BPH underwent an experimental stress task (public speaking, videotaped). The degree of stress was defined physiologically as rises in cortisol and blood pressure. Personal appraisal of the situation was not assessed. Subjects showing stronger stress responses were found to have larger prostate volume and more objective and subjective indications of urinary tract dysfunction. Among the hypotheses for this relationship were decreased apoptosis (slowed prostatic cell death) as a result of chronically greater sympathetic input; increased pelvic floor muscle tension; greater prostate contractility (stimulated by exogenous epinephrine and norepinephrine); and stress-induced hyperinsulinaemia promoting prostate growth. Not all BPH cases involve pain, but when pain is present it can stimulate the sympathetic system, create a feedback loop, and add to the problem.

Anderson et al. (2005, 2008, 2009) compared men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) with asymptomatic controls for evidence of differences in stress levels. Various psychological tests revealed more perceived stress and anxiety in the CPPS patients, plus more somatization, hostility, interpersonal sensitivity and paranoid ideation. Salivary cortisol on awakening was also measured and found to be significantly higher in the pain patients. This rise in cortisol is thought to indicate the hippocampus preparing the HPA axis for anticipated stress. Cortisol has been found to be higher in situations such as waking on the day of a dance competition (Rohleder et al. 2007), in high-school teachers reporting higher job strain (Steptoe et al. 2000), and waking on work days compared with weekends (Schlotz et al. 2004).

Anderson and Wise have advanced an explanation of chronic, otherwise unexplained pelvic pain as frequently stemming from myofascial trigger points (Wise & Anderson 2008) (see Chapter 16). In their view, much long-term pelvic pain develops from the shortening and tensing of pelvic muscles, eventually creating and then aggravating trigger points, and this condition can be treated with manual release techniques. The more complete treatment, however, involves cultivating a skill for dropping into deep relaxation along with changing attention (‘paradoxical relaxation’) in a way that contradicts the usual tensing and bracing against pain. This is achieved (in their programme) by progressively more muscular and emotional self-calming.

Trigger points were shown to be exacerbated by stressful emotion (Hubbard & Berkoff 1993, McNulty et al. 1994). EMG was recorded from an upper trapezius trigger point along with a signal from an adjacent area of the muscle without a trigger point. As emotional stress increased, the trigger point EMG increased its voltage even though the rest of the muscle did not. Also, described in Chen et al. (1998) was a demonstration of how electrical activity associated with trigger points in rabbits was abolished by phentolamine, a sympathetic antagonist. This supports the role of the autonomic nervous system in maintaining trigger points, and also is congruent with the cited research on the aggravating effect of negative emotion (anxiety) on trigger points (Simons 2004). Wise and Anderson’s protocol for pelvic pain treatment includes both thorough relaxation training and manual release of trigger points. One is temporarily curative, the other preventive.

Alexithymia and pelvic pain

The word ‘alexithymia’ refers to a relative inability to name feelings, or to verbally elaborate on feeling states. Its Greek roots belie its recent creation, less than 40 years ago, by psychiatrist Peter Sifneos (1973). The phenomenon and the concept existed long before its final naming. Physicians and psychotherapists had noted for many years the tendency of some patients to use very few words to describe their feelings; complex emotional states were reduced to simple terms such as ‘feeling bad’ or ‘upset’ without elaboration. This difficulty with feelings includes reflecting on them, naming them, discussing them and expressing them.

Researchers have pursued correlations between high scores on alexithymia scales such as the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (Bagby et al. 2006) and other problems such as dissociation, Asperger’s, autism, substance abuse, anorexia nervosa, somatic amplification and somatoform disorders. A functional disconnection between the two cerebral hemispheres or a right hemisphere deficit has been suggested, with incomplete evidence (Tabibnia & Zaidel 2005).

Most research on chronic pain and alexithymia has found a correlation between them. Celikel and Saatcioglu (2006) found that female chronic pain patients scored more than twice as high on alexithymia scales as controls, and there was also a positive correlation between alexithymia scores and duration of pain. Since the study design was not intended to distinguish direction of causation, it is conceivable that prolonged pain damages the right hemisphere, interfering with full experiencing and transfer of emotional material.

Porcelli et al. (1999) found a strong association between alexithymia and functional gastrointestinal disorders (66% had high alexithymia scores, whereas the population average is below 10%), and later (Porcelli et al. 2003) demonstrated that higher alexithymia scores predicted worse treatment outcome. Although anxiety and depression also predicted worse treatment outcome, the alexithymia scores were stable and independent of anxiety and depression, suggesting a unique contribution to failure to improve.

Hosoi et al. (2010) studied 129 patients with chronic pain from muscular dystrophy. Degree of alexithymia was significantly associated with higher pain intensity and more pain interference. Finally, Lumley et al. (1997) compared chronic pain patients to patients seeking treatment for obesity and nicotine dependence, to control for the variable of ‘treatment-seeking’. As predicted, the chronic pain patients scored higher on the alexithymia measures than either of the other groups. They also had higher levels of psychopathology, which can by itself confound and weaken treatment programmes for chronic pain.

Processing of emotional experience often involves revisiting traumatic or otherwise disturbing memories, which can be done alone or with the help of a friend, relative or therapist. Psychologist James Pennebaker has led the way in a body of research that repeatedly confirms the value of simply writing about undisclosed experiences and the deep feelings that have been kept private (Berry & Pennebaker 1993; Pennebaker 1997). This process of transforming inchoate memories and feelings into a linear, word-based account of an experience seems to be a key step in ‘adjusting’ to something unpleasant. Part of the value of psychotherapy lies in providing a safe forum for verbalizing one’s feelings about something for the first time, and this activity has therapeutic value regardless of response from another person.

This self-adjusting activity, however, is precisely what the individuals describable as ‘alexithymic’ are not good at. Their poverty of verbal labels for body sensations related to emotional states is their defining characteristic, and may block necessary processing of experiences in real time. Emotional adjustment and acceptance benefit from review, reflection, hindsight, considering contextual factors, and if possible, ‘normalization’ by an accepting and supportive listener. Pennebaker (2004) has concluded that undisclosed disturbing experiences cause persistent conflict, partly over-suppressing them; the topic stimulates ruminative worry, and this eventually has ill-health effects. Graham et al. (2008) showed that in a large group of chronic pain patients, writing about their anger constructively resulted in better control over both pain and depression, compared with another chronic pain group asked to write about their goals. Junghaenel et al. (2008) also studied the effects of written self-disclosure on chronic pain patients, and found that only those with ‘interpersonally distressed’ characteristics (denoting deficient social support, feeling left alone, etc.) benefited from the expressing of emotional events.

The main thrust of research with alexithymia has been in the areas of somatizing, trying to characterize the ‘psychosomatic’ patient as deficient in this way. One of the largest surveys of this association, studying over 5000 Finnish citizens, found a clear association between somatization and alexithymia (Mattila et al. 2008). Factors such as depression, anxiety and sociodemographic variables were controlled for, and the association remained. The TAS-20 factor scale labeled ‘Difficulty Identifying Feelings’ was the strongest common denominator between alexithymia and somatization.

Pain catastrophizing and fear-avoidance

Many instances of chronic pelvic pain have an obscure or unknown aetiology, and are associated with other symptoms such as comorbid psychiatric conditions (anxiety, depression), and a tendency toward emotion-triggered multiple somatic complaints over time (‘somatizing’). Treating such patients as if they have bona fide medical conditions, when such evidence is lacking, is at best incomplete. Such patients may respond to analgesic medications, but they often respond better to a biopsychosocial approach which addresses interpersonal factors, anxiety, apprehension and catastrophic thinking about the meaning of the pain, plus attention to muscle-bracing, movement and breathing patterns, and sensory awareness (Haugstad et al. 2006).

‘Pain catastrophizing’ is a psychological variable easily measured by questionnaires such as the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) (Sullivan et al. 1995, 2001) or the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (McCracken et al. 1992, Burns et al. 2000). These scales quantify negative expectations about pain and include subfactors such as helplessness, degree of suffering and disability expected, estimated ability to cope with the pain, and feeling overwhelmed.

Sample comments from questions from the PCS include:

Pain catastrophizing as a cognitive process may get stronger as pain gets worse, but it also varies independently of pain intensity. For example, in a prospective study, Flink et al. (2009a) studied childbirth and pain. Eighty-eight women were assessed for pain catastrophizing before they gave birth. Those scoring higher in this variable reported subsequent higher pain and poorer physical recovery (measured as activity levels) as compared with those with lower prebirth pain catastrophizing scores. Since this was not an intervention study, it could be argued that the high-scoring women knew that their pain would be worse. But intervention studies which alter pain catastrophizing have been successful in altering various aspects of the reaction to pain (Voerman et al. 2007, van Wilgen et al. 2009).

Smeets et al. (2006) studied chronic low back pain patients going through either physical or cognitive-behavioural treatment, and found that in both intervention groups, pain catastrophizing was a mediating variable for improvement in pain intensity and disability. Thorn et al. (2007) used a RCT design with wait-list control to study the response of chronic headache sufferers to cognitive change techniques, with particular attention to changes in catastrophic thinking. The active treatment group had significant improvements in affect, anxiety and self-efficacy regarding headache management. About half of them also had clinically meaningful reductions in headache indicators that did not occur in the control group.

Tripp et al. (2006) studied certain characteristics in 253 men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS). Magnitude of both sensory pain and affective pain could be predicted by degree of what was termed ‘helpless catastrophizing’.

The physiological mediators in pain catastrophizing are largely unknown, but Wolff et al. (2008) showed that the combination of higher paraspinal muscle tension and high catastrophizing predicted high reported pain levels. Muscle tension in this study was not a simple mediating factor, but if resting low back tension was already high, then the co-occurrence of catastrophic thinking amplified the perception of back pain.

Lowering pain intensity is not the only desirable treatment outcome. A study of reducing pain in patients in an emergency deparement (Downey & Zun 2009) instructed patients in slow deep breathing, and in this brief intervention found no significant reduction in pain as estimated by the patients, but there were still significant improvements in rapport with treating physicians, greater willingness to follow the recommendation and numerous statements that the intervention was useful. Another study of back pain patients (Flink 2009b) showed that practising breathing exercises had not so much effect on actual pain levels as it did on less catastrophizing and pain-related distress, along with greater acceptance of the pain condition.

Hypervigilance and fear of movement

One related psychological variable relevant to pain perception is called ‘hypervigilance’. This can be measured in several ways, including magnitude of startle response. The factor of unpredictability, basically an absence of reliable threat cues, seems to amplify vigilance, and the Pain Vigilance and Awareness Questionnaire is designed to measure the vigilance specifically for pain (Roelofs et al. 2003). Hypervigilance was also assessed in a group of 54 young male patients one day before chest-correction surgery (Lautenbacher et al. 2009). Subjective ratings of pain intensity 1 week later were significantly predicted by degree of hypervigilance; the more watchful the patients were, the more pain they reported.

The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) measures fear of movement instead of fear of pain directly (French et al. 2007). This shows a conditioning effect in which the organism with repeated noxious experiences becomes sensitive to earlier and earlier cues. So if a certain pelvic movement causes pain, the fear of pain will inhibit that movement. Some people generalize from this association more drastically than others: perhaps from only that one particular pelvic movement to all related pelvic movements, or – ‘just to be safe’ – nearly any body movement at all.

Sample items from the TSK scale include:

All these questionnaires seem to tap slightly different aspects of a central quality related to fear and avoidance. As Roelofs et al. put it (2003): ‘With regard to the convergent validity, the Pain Vigilance and Awareness Questionnaire was highly correlated with related constructs such as the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS), and Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK)’. What such questionnaires tap is related to anxiety, broadly conceived, and with components of depression such as helplessness and loss of hope. Pain studies may not differentiate subcategories of these broader conditions and so end up blaming anxiety and depression for exacerbating chronic pain.

Avoidance of sexual activity

The correlation between degree of pelvic pain and normal sexual activity is not as great as one might think. Emotional factors that facilitate or inhibit sexual activity are many, and include capacity for sustained intimacy, gender identity, general sense of self-worth, baseline desire, relationship quality and comfort with sex in general. Prolonged avoidance of sex can result from a short-sighted withdrawal from situations associated with pain, past or present. Deconditioning through disuse can occur just as easily in sex organs as in the legs or back muscles. Desrochers et al. (2010) found that baseline fear of pain and catastrophizing were strong predictors of eventual success in a programme targeting provoked vulvodynia, and success included return to normal sexual activity. Desrochers et al. (2009) also presented evidence that psychological variables such as catastrophizing, hypervigilance and fear of pain predicted sexual impairment in women with provoked vestibulodynia. This means that pain magnitude is not linearly correlated with sexual functioning; actual pain is only part of the picture, sometimes overshadowed by cognitive and affective variables. There is a wide range of variability between loss of sexual desire and intensity of sexual pain.

Reissing et al. (2004) investigated the accuracy of the usual criteria for diagnosis of vaginismus, which is usually considered a simple muscle spasm problem. Using the factors of degree of vaginal spasm and pain, women previously diagnosed with vaginismus were not significantly different from women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome, but they could be differentiated by higher vaginal muscle tone (with lower muscle strength) and more defensive and avoidant distress behaviours. The authors concluded: ‘These data suggest that the spasm-based definition of vaginismus is not adequate as a diagnostic marker for vaginismus. Pain and fear of pain, pelvic floor dysfunction, and behavioral avoidance need to be included in a multidimensional reconceptualization of vaginismus’.

For instance, a large study in China surveyed 291 men with chronic prostatitis and pelvic pain for degree of anxiety and depression as they underwent a 6-week treatment programme. Other factors expected to affect treatment outcome were also assessed: age, a prostatitis symptom index, and leukocyte count. None of these were predictive of treatment success, but the psychological variables of anxiety and depression were. The authors concluded: ‘Such psychological obstacles as anxiety and depression play an important role in the pathogenesis, development and prognosis of CP/CPPS’. The psychophysiological link in this case is unknown, but may involve chronic restriction of pelvic or prostate circulation (Li et al. 2008).

Finally, the variable of self-efficacy has been found to be correlated with both chronic pain and alexithymia. Physical self-efficacy – meaning roughly self-confidence in one’s physical capacity – is modifiable to a degree, with favourable health consequences. A study by Pecukonis (2009) found two initial differences between a sample of patients with chronic intractable back pain and a matched control group. The pain group was significantly higher in alexithymia and lower in physical self-efficacy (self-estimate of strength, endurance and ability to perform physically). Foster et al. (2010) found that ‘pain self-efficacy’ was a strong predictor of recovery from chronic pain, independently of depression, pain catastrophizing and fear of movement. Having a self-concept that includes resilience and capacity to recover is important for participating fully in treatment programmes for any kind of chronic pain.

This quality was pinpointed also in Albert Bandura’s 1987 study teaching subjects to withstand experimental pain, using cognitive techniques to boost self-efficacy. The study design included the opioid-blocking chemical naloxone to control for the effects of opiate pain medication administered at certain points. The outcome supported the value of cognitive training to boost pain control. In the author’s words: ‘…subjects who expressed efficacious judgments regarding their ability to manage pain experienced as much relief from their symptoms as subjects receiving opioid analgesics or placebo’ (Bandura et al. 1987).

The advantage of an experimental pain stimulus is that its intensity and location can be adjusted in order to measure pain thresholds, usually via a thermal stimulus or by intramuscular hypertonic saline infusions. In one such study (Chalaye et al. 2009) pain intensity diminished, as measured by subject ratings (subjective thresholds), in response to slow deep breathing at a rate of six per minute. Another result in that study was the increase in heart rate variability, which correlates with increased vagal tone and general lowering of arousal.

• Chronic pain is best treated with a combined approach that includes attention to thinking, emotions and behaviour, as well as medicine and physical therapy.

• Stressful emotions can aggravate pain conditions. Denying feelings or pushing them away will not block their effects.

• Think about what else besides pain provokes your worst anxiety and stress. Look for situations and feelings that coincide with your pain getting worse.

• Learn to relax, physically and mentally, instead of tensing up with pain. This will give you more control over the pain and your reactions to it.

• Don’t over-react to what hasn’t even happened yet. Expecting the worst when it rarely happens activates more physical upset, which can amplify pain reception.

• Activity keeps your body healthier and will stimulate more healing. Don’t avoid movement on the chance that it might hurt.

• Practice breathing slowly to compose yourself. Find ways to feel secure and calm, because this will work against pain.

• Regardless of pelvic pain, avoiding sex can make things worse. The system benefits from normal activity.

• Try writing about your deepest feelings, the things you never told anybody. There’s no need to show it to anyone; just read it back to yourself.

• Do some reading about chronic pain and figure out how you can participate in your own treatment. Doctors can’t do it all.

Defensiveness, emotional denial and repression

This group of inter-related psychological variables refers to how individuals manage negative emotions, whether personally related (shame, guilt, blame), by denying faults and stress, or by denying negative feelings such as anger and hostility. Burns (2000a) thoroughly reviewed the concept of emotional repression in relation to chronic pain, updating it from its roots in psychoanalysis, and incorporated modern research to make it relevant to current understandings of chronic pain. The conceptual gap between such subjective variables as blocking or denying negative feelings and experiencing somatic pain has been narrowed by psychophysiological research. The evidence supports such a connection in cases where denial of negative feelings coincides with high physiological and/or behavioural reactivity to stress. This mismatch apparently gives rise to conflict, with physiological effects, and correlates with increased pain and poor response to multidisciplinary pain management programmes (Burns 2000b).

Placebo-nocebo chemistry as psychophysiology

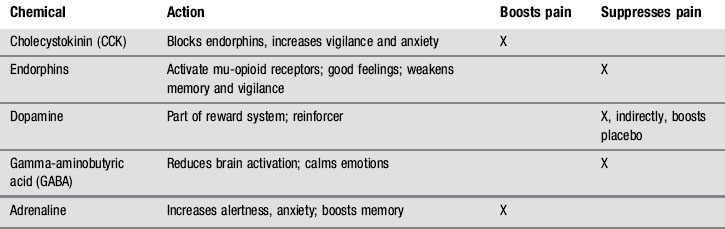

The relaxation effect acts like a mental lever, affecting the entire pain modulation system. Pain intensity can be adjusted not only with opiates, but also by altering the naturally occurring endogenous opiates (endorphins) and their receptors (Hoffman et al. 2005). Emotional changes accompanying relaxation also affect the proportions of other pain-related biochemicals, such as GABA, cholecystokinin (CCK), dopamine and adrenaline (epinephrine).

Work with mu-opioid receptors has revealed that endorphins serve a more complex role than simply muffling pain. Endorphins also affect motivation and behaviour: low endorphin levels stimulate more alertness and vigilance, preparation for defence, sharper memory, faster reflexes for actions such as limb withdrawal, and a general increase in qualities favouring survival and mobilization of energy. High endorphin levels, in contrast, are associated with somnolence, reduced vigilance, and a sense of well-being. Memory and alertness are reduced, as well as pain sensitivity (Fields 2004).

Endorphins and other pain-related chemicals can be manipulated by triggering expectations in experimental subjects, both humans and animals. Conditioned placebos of any sort will diminish pain (for instance, a cue that has been associated with a pain-relieving injection). Using a ‘nocebo’ (an inert substance or stimulus that creates the expectation of worse pain) will make pain worse (Benedetti 2006, Benedetti et al. 2005, 2007). Even words of warning before an injection – ‘This might hurt a little’ – will increase pain perception more than will reassurance or distraction. These rapid adjustments to pain intensity are created by alterations in mu-opioid receptor sensitivity as well as changes in endorphin release. There are also changes in the anterior cingulate cortex, periaqueductal grey, and other brain sites known to be involved in pain modulation. Finally, administering morphine also turns off certain pain-gating cells in the rostral ventromedial nucleus and facilitates descending inhibitory circuits which inhibit dorsal horn neurons (Wager 2007). fMRI and PET scans of opioid receptor sites have confirmed the actions of pain-gating neurons (Scott et al. 2007).

Table 4.1 shows the relevant chemistry and interactions.

Effects of physical and sexual abuse

Researchers examining this variable sometimes distinguish early from later (adult) physical abuse and sexual abuse, although they can overlap. Lampe et al. (2003) concluded that ‘Childhood physical abuse, stressful life events, and depression had a significant impact on the occurrence of chronic pain in general, whereas childhood sexual abuse was correlated with CPP only’.

Vulvodynia may be a distinctly different disorder than CPP. Reed et al. (2000), generalizing from a small sample, described evidence that vulvodynia patients were not significantly different from control subjects in most psychological or historical variables. Those with chronic pelvic pain, however, were more likely to report a history of sexual or physical abuse, depression and more somatic complaints. Bodden-Heidrich et al. (1999) supported this distinction between the two diagnoses, finding in a comparison of vulvodynia with CPP patients that the latter as a group showed more history of sexual abuse and ‘severe psychological problems’.

A study (Heim et al. 1998) of CPP using neuroendocrine assessment of HPA axis activity implicated blunted cortisol response. Compared with normals, a large proportion of CPP subjects reported physical and/or sexual abuse history, and post-traumatic stress disorder-like symptoms were commonly reported. There were similarities to other long-term disorders such as fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis and chronic fatigue syndrome. Reduced cortisol response to stressful conditions impairs energy availability, promotes pain and inflammation by allowing prostaglandins to rise, and permits more of the damaging effects of the stress response, including autoimmunity and susceptibility to chronic pain. The authors concluded that abuse history seems to promote, in many cases, a long-term maladjustment in endocrine aspects of the stress response system, making chronic pain disorders, including CPP, more likely.

Collett et al. (1998) found that the lifetime incidence of sexual abuse was significantly higher in women with CPP, but physical abuse history was comparable in CPP patients and women with non-pelvic chronic pain complaints. Walker et al. (1992) studied psychological characteristics of women with CPP and noted a higher likelihood of dissociation as a coping mechanism, compared with a control group. Women with CPP had more evidence of current psychological distress, somatization, lower vocational and social functioning, and amplification of physical symptoms. In this study also, they were significantly more likely to have experienced severe childhood sexual abuse.

Somatization

Two articles from Austria recommended routine evaluation for psychological aspects of CPP. Maier et al. (1999) summarized experience with 220 women with CPP who were examined in collaboration between the Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology and the Psychosomatic Department in the St. Johann’s Hospital of Salzburg. The patients received both laparoscopic examination and psychological evaluation; the researchers found that somatization was a frequent explanation for the symptoms. Standard somatic medicine, according to the authors, could not explain the discrepancies between the intensity of reported pain and the pathophysiology. They recommended continued engagement of the patients in order to facilitate psychotherapy or consideration of psychological input to the problem. The alternative outcome, ignoring psychological features, carries the risk of ‘chronification of CPP in patients approached only in somatic terms’.

Greimel & Thiel (1999), at the University Hospital in Graz, Austria, put forth a similar view: that emphasizing medical approaches to CPP increases the patient’s belief that medical (pharmaceutical, surgical) remedies will give them relief. In their view, the majority of CPP patients have evidence of somatoform disorder, which calls for psychological interventions rather than medical.

In making decisions about CPP treatment, psychosocial factors could be considered from the beginning, but more usually the medical approach is started first, to ‘rule out’ physical aetiology before psychological and behavioural intervention is even considered. This issue was addressed by one study by Peters et al. (1991) which compared the outcomes of these two approaches. One group of CPP patients began with laparoscopic examination to look for somatic problems before doing anything else. The second group was examined for many factors simultaneously: psychological, physiotherapeutic, dietary, environmental and somatic. At one-year follow-up, those receiving the second (‘integrated’) approach had done significantly better with pain management, and laparoscopic assessment seemed to add little to the results. This conclusion may indicate the advantage of not biasing patients toward a medical solution; otherwise, if no clear-cut medical disorder is found, the patients must re-orient to considering psychological, behavioural and experiential history factors. They can easily feel prematurely cast out and stereotyped.

Carrico et al. (2008) approached interstitial cystitis as amenable to guided imagery, and mounted a study in which guided imagery specific to interstitial cystitis (IC) was developed, recorded and given to IC patients. The recordings contained imagery and suggestions for healing the bladder, relaxing pelvic floor muscles and quieting the nerves supplying the pelvic area. Recordings were to be listened to twice a day for 25 minutes, while the control group simply relaxed for the same amount of time. Results clearly favoured the imagery group, who had significantly more reduced pain, urinary urgency and other symptoms of IC compared with the control group. This approach is remarkably simple and inexpensive, yet brought respectable results to many of the participants.

Anderson R.U., Wise D., Sawyer T., Chan C. Integration of myofascial trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training treatment of chronic pelvic pain in men. J. Urol.. 2005;174(1):155-160.

Anderson R.U., Orenberg E.K., Chan C.K., Morey A., Flores V. Psychometric profiles and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J. Urol.. 2008;179:956-960.

Anderson R.U., Orenberg E.K., Morey A., Chavez N., Chan C.A. Stress induced hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis responses and disturbances in psychological profiles in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J. Urol.. 2009;182(5):2319-2324.

Bagby R.M., Taylor G.J., Parker J.D.A., Dickens S. The development of the Toronto Structured Interview for Alexithymia: Item selection, factor structure, reliability and concurrent validity. Psychother. Psychosom.. 2006;75:25-39.

Bandura A., O’Leary A., Taylor C.B., Gauthier J., Gossard D. Perceived self-efficacy and pain control: opioid and nonopioid mechanisms. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.. 1987;53(3):563-571.

Benedetti F. The biochemical and neuroendocrine bases of the hyperalgesic nocebo effect. J. Neurosci.. 2006;26(46):12014-12022.

Benedetti F., Mayberg H.S., Wager T.D., Stohler C.S., Zubieta J.K. Neurobiological mechanisms of the placebo effect. J. Neurosci.. 2005;25(45):10390-10402.

Benedetti F., Lanotte M., Lopiano L., Colloca L. When words are painful: unraveling the mechanisms of the nocebo effect. Neuroscience. 2007;147(2):260-271.

Berry D.S., Pennebaker J.W. Nonverbal and verbal emotional expression and health. Psychother. Psychosom.. 1993;59(1):11-19.

Bodden-Heidrich R., Küppers V., Beckmann M.W., Ozörnek M.H., Rechenberger I., Bender H.G. Psychosomatic aspects of vulvodynia. Comparison with the chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J. Reprod. Med.. 1999;44(5):411-416.

Burns J.W. Repression in chronic pain: an idea worth reconsidering. Appl, Prevent. Psychology. 2000;9:173-190.

Burns J.W. Repression predicts outcome following multidisciplinary treatment of chronic pain. Health Psychol.. 2000;19(1):75-84.

Burns J.W., Mullen J.T., Higdon L.J., Wei J.M., Lansky D. Validity of the pain anxiety symptoms scale (PASS): prediction of physical capacity variables. Pain. 2000;84(2–3):247-252.

Carrico D.J., Peters K.M., Diokno A.C. Guided imagery for women with interstitial cystitis: results of a prospective, randomized controlled pilot study. J. Altern. Complement. Med.. 2008;14(1):53-56.

Celikel F.C., Saatcioglu O. Alexithymia and anxiety in female chronic pain patients. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;5:13.

Chalaye P., Goffaux P., Lafrenaye S., Marchand S. Respiratory effects on experimental heat pain and cardiac activity. Pain Med.. 2009;10(8):1334-1340.

Chen J.T., Chen S.M., Kuan T.S., Chung K.C., Hong C.Z. Phentolamine effect on the spontaneous electrical activity of active loci in a myofascial trigger spot of rabbit skeletal muscle. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.. 1998;79(7):790-794.

Collett B.J., Cordle C.J., Stewart C.R., Jagger C. A comparative study of women with chronic pelvic pain, chronic nonpelvic pain and those with no history of pain attending general practitioners. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol.. 1998;105(1):87-92.

Desrochers G., Bergeron S., Khalifé S., Dupuis M.J., Jodoin M. Fear avoidance and self-efficacy in relation to pain and sexual impairment in women with provoked vestibulodynia. Clin. J. Pain. 2009;25(6):520-527.

Desrochers G., Bergeron S., Khalifé S., Dupuis M.J., Jodoin M. Provoked vestibulodynia: psychological predictors of topical and cognitive-behavioral treatment outcome. Behav. Res. Ther.. 2010;48(2):106-115.

Downey L.V., Zun L.S. The effects of deep breathing training on pain management in the emergency department. South. Med. J.. 2009;102(7):688-692.

Fields H. State-dependent opioid control of pain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.. 2004;5(7):565-575. (review)

Flink I.K., Mroczek M.Z., Sullivan M.J., Linton S.J. Pain in childbirth and postpartum recovery: the role of catastrophizing. Eur. J. Pain. 2009;13(3):312-316.

Flink I.K., Nicholas M.K., Boersma K., Linton S.J. Reducing the threat value of chronic pain: A preliminary replicated single-case study of interoceptive exposure versus distraction in six individuals with chronic back pain. Behav. Res. Ther.. 2009;47(8):721-728.

Foster N.E., Thomas E., Bishop A., Dunn K.M., Main C.J. Distinctiveness of psychological obstacles to recovery in low back pain patients in primary care. Pain. 2010;148(3):398-406.

French D.J., France C.R., Vigneau F., French J.A., Evans R.T. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic pain: a psychometric assessment of the original English version of the Tampa scale for kinesiophobia (TSK). Pain. 2007;127(1–2):42-51.

Graham J.E., Lobel M., Glass P., Lokshina I. Effects of written anger expression in chronic pain patients: making meaning from pain. J. Behav. Med.. 2008;31(3):201-212.

Greimel E.R., Thiel I. Psychological treatment aspects of chronic pelvic pain in the woman. Wien. Med. Wochenschr.. 1999;149(13):383-387. [Article in German]

Haugstad G.K., Haugstad T.S., Kirste U.M., et al. Posture, movement patterns, and body awareness in women with chronic pelvic pain. J. Psychosom. Res.. 2006;61(5):637-644.

Heim C., Ehlert U., Hanker J.P., Hellhammer D.H. Abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder and alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in women with chronic pelvic pain. Psychosom. Med.. 1998;60(3):309-318.

Hoffman G.A., Harrington A., Fields H.L. Pain and the placebo: what we have learned. Perspect. Biol. Med.. 2005;48(2):248-265.

Hosoi M., Molton I.R., Jensen M.P., et al. Relationships among alexithymia and pain intensity, pain interference, and vitality in persons with neuromuscular disease: considering the effect of negative affectivity. Pain. 2010;149(2):273-277.

Hubbard D.R., Berkoff G.M. Myofascial trigger points show spontaneous needle EMG activity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993;18(13):1803-1807.

Junghaenel D.U., Schwartz J.E., Broderick J.E. Differential efficacy of written emotional disclosure for subgroups of fibromyalgia patients. Br. J. Health Psychol.. 2008;13(Pt 1):57-60.

Kirste U., Haugstad G.K., Leganger S., Blomhoff S., Malt U.F. Chronic pelvic pain in women. Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen.. 2002;122(12):1223-1227. (article in Norwegian)

Lampe A., Doering S., Rumpold G., et al. Chronic pain syndromes and their relation to childhood abuse and stressful life events. J. Psychosom. Res.. 2003;54(4):361-367.

Lautenbacher S., Huber C., Kunz M., et al. Hypervigilance as predictor of postoperative acute pain: its predictive potency compared with experimental pain sensitivity, cortisol reactivity, and affective state. Clin. J. Pain. 2009;25(2):92-100.

Li H.C., Wang Z.L., Li H.L., et al. Correlation of the prognosis of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome with psychological and other factors: a Cox regression analysis [Article in Chinese]. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2008;14(8):723-727.

Lumley M.A., Asselin L.A., Norman S. Alexithymia in chronic pain patients. Compr. Psychiatry. 1997;38(3):160-165.

Maier B., Akmanlar-Hirscher G., Krainz R., Wenger A., Staudach A. Chronic pelvic pain – a still too little appreciated disease picture. Wien. Med. Wochenschr.. 1999;149(13):377-382. (article in German)

Mattila A.K., Kronholm E., Jula A., Salminen J.K., Koivisto A.M., Mielonen R.L., et al. Alexithymia and somatization in general population. Psychosom. Med.. 2008;70(6):716-722.

Marenbon J. Medieval Philosophy: an historical and philosophical introduction. London: Routledge; 2007.

McCracken L.M., Zayfert C., Gross R.T. The Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale: development and validation of a scale to measure fear of pain. Pain. 1992;50(1):67-73.

McNulty W.H., Gevirtz R.N., Hubbard D.R., Berkoff GM. Needle electromyographic evaluation of trigger point response to a psychological stressor. Psychophysiology. 1994;31(3):313-316.

Pecukonis E.V. Physical self-efficacy and alexithymia in women with chronic intractable back pain. Pain Manag. Nurs.. 2009;10(3):116-123.

Pennebaker J.W. The Healing Power of Expressing Emotions. NY: Guilford Press; 1997.

Pennebaker J.W. Writing to Heal. Oakland CA: New Harbinger Press; 2004.

Peters A.A., van Dorst E., Jellis B., van Zuuren E., Hermans J., Trimbos J.B. A randomized clinical trial to compare two different approaches in women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet. Gynecol.. 1991;77(5):740-744.

Pontari M.A., Ruggieri M.R. Mechanisms in prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J. Urol.. 2004;172(3):839-845.

Porcelli P., Taylor G.J., Bagby R.M., De Carne M. Alexithymia and functional gastrointestinal disorders: A comparison with inflammatory bowel disease. Psychother. Psychosom.. 1999;68:263-269.

Porcelli P., Bagby R.M., Taylor G.J., De Carne M., Leandro G., Todarello O. Alexithymia as predictor of treatment outcome in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Psychosom. Med.. 2003;65:911-918.

Reed B.D., Haefner H.K., Punch M.R., et al. Psychosocial and sexual functioning in women with vulvodynia and chronic pelvic pain. A comparative evaluation. J. Reprod. Med.. 2000;45(8):624-632.

Reissing E.D., Binik Y.M., Khalifé S., Cohen D., Amsel R. Vaginal spasm, pain, and behavior: an empirical investigation of the diagnosis of vaginismus. Arch. Sex. Behav.. 2004;33(1):5-17.

Roelofs J., Peters M.L., McCracken L., Vlaeyen J.W. The pain vigilance and awareness questionnaire (PVAQ): further psychometric evaluation in fibromyalgia and other chronic pain syndromes. Pain. 2003;101(3):299-306.

Rohleder N., Beulen S.E., Chen E., Wolf J.M., Kirschbaum C. Stress on the dance floor: the cortisol stress response to social-evaluative threat in competitive ballroom dancers. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull.. 2007;33(1):69-84.

Schlotz W., Hellhammer J., Schulz P., Stone A.A. Perceived work overload and chronic worrying predict weekend-weekday differences in the cortisol awakening response. Psychosom. Med.. 2004;66(2):207-214.

Scott D.J., Stohler C.S., Egnatuk C.M., Wang H., Koeppe R.A., Zubieta J.K. Individual differences in reward responding explain placebo-induced expectations and effects. Neuron. 2007;55(2):325-336.

Sifneos P.E. The prevalence of ‘alexithymic’ characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychother. Psychosom.. 1973;22(2):255-262.

Simons D.G. Review of enigmatic MTrPs as a common cause of enigmatic musculoskeletal pain and dysfunction. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.. 2004;14(1):95-107.

Smeets R.J., Vlaeyen J.W., Kester A.D., Knottnerus J.A. Reduction of pain catastrophizing mediates the outcome of both physical and cognitive-behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. J. Pain. 2006;7(4):261-271.

Steptoe A., Cropley M., Griffith J., Kirschbaum C. Job strain and anger expression predict early morning elevations in salivary cortisol. Psychosom. Med.. 2000;62:286-292.

Sullivan M.J.L., Bishop S.R., Pivik J., et al. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psych. Assessment. 1995;7(4):524-532.

Sullivan M.J.L., Thorn B., Haythornthwaite J.A., et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin. J. Pain. 2001;17:52-64.

Tabibnia G., Zaidel E. Alexithymia, interhemispheric transfer, and right hemispheric specialization: a critical review. Psychother. Psychosom.. 2005;74(2):81-92.

Thorn B.E., Pence L.B., Ward L.C., et al. A randomized clinical trial of targeted cognitive behavioral treatment to reduce catastrophizing in chronic headache sufferers. J. Pain. 2007;8(12):938-949.

Tripp D.A., Nickel J.C., Wang Y., et alNational Institutes of Health-Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network (NIH-CPCRN) Study Group. Catastrophizing and pain-contingent rest predict patient adjustment in men with chronicprostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J. Pain. 2006;7(10):697-708.

Ullrich P.M., Lutgendorf S.K., Kreder K.J. Physiologic reactivity to a laboratory stress task among men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2007;70(3):487-492.

van Wilgen C.P., Dijkstra P.U., Versteegen G.J., Fleuren M.J., Stewart R., van Wijhe M. Chronic pain and severe disuse syndrome: long-term outcome of an inpatient multidisciplinary cognitive behavioural program. J. Rehabil. Med.. 2009;41(3):122-128.

Voerman G.E., Sandsjö L., Vollenbroek-Hutten M.M., et al. Changes in cognitive-behavioral factors and muscle activation patterns after interventions for work-related neck-shoulder complaints: relations with discomfort and disability. J. Occup. Rehabil.. 2007;17(4):593-609.

Wager T.D. Placebo effects on human mu-opioid activity during pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 2007;104(26):11056-11061.

Walker E.A., Katon W.J., Neraas K., Jemelka R.P., Massoth D. Dissociation in women with chronic pelvic pain. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1992;149(4):534-537.

Wise D., Anderson R.A. Headache in the Pelvis, fifth ed. Occidental, CA: National Center for Pelvic Pain; 2008.

Wolff B., Burns J.W., Quartana P.J., Lofland K., Bruehl S., Chung O.Y. Pain catastrophizing, physiological indexes, and chronic pain severity: tests of mediation and moderation models. J. Behav. Med.. 2008;31(2):105-114.