13 Practical anatomy, examination, palpation and manual therapy release techniques for the pelvic floor

Female practical anatomy

Planes of examination

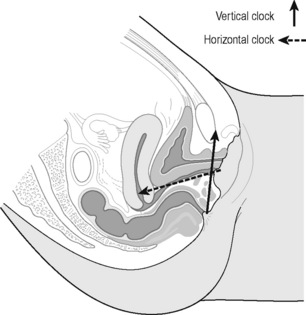

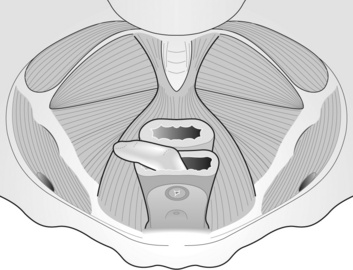

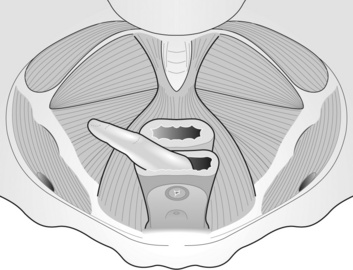

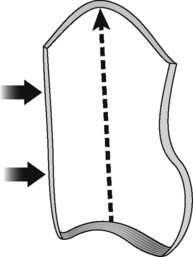

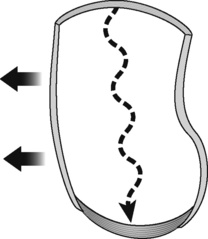

‘It is important to recognise that the pelvic diaphragm is not flat or bowl-shaped as is frequently depicted. At the urogenital and anal hiatus the muscles lie in a near vertical configuration and behind the anus they flatten to form a nearly horizontal diaphragm’ (Brooks et al. 1998). The examination of the patient most frequently takes place in the crook lying position. As the examiner faces the patient the perineum from the pubic bone to the supporting surface is visualized on a clock; this was first described by Laycock & Jerwood (2001).

During this part of the examination palpating from the vertical clock to the horizontal clock it should be visualized that the vagina extends inward from the vestibule at a 45° angle and then turns horizontal over the levator plate (Brooks 2007). The ‘horizontal clock’ runs for purposes of description perpendicular to the vertical but is clearly not completely perpendicular; the coccyx here is at 12 o’clock and the perineal body again is at 6 o’clock (Figures 13.1, 13.2) (Whelan 2008). It should also be stated that the pelvic floor and the structures of the pelvis are multidimensional and it can be difficult to visualize the many different planes. This suggested method of examination is based on two planes only but the examiner will appreciate the overlap into other planes.

Practical anatomy on the vertical clock – External perineal

The examination on the vertical clock has two parts, the external first and then the internal. The external genitalia are observed for lesions, erythema and colour changes before the soft tissue assessment begins. The conditions that may affect the external genitalia in chronic pelvic pain are discussed in Chapter 8; however, the therapist should be familiar with symptoms and appearance of dermatological conditions such as dermatitis, lichens planus and lichens sclerosus and be aware of the occurrence of thrush and sexually transmitted infections including genital herpes and genital warts.

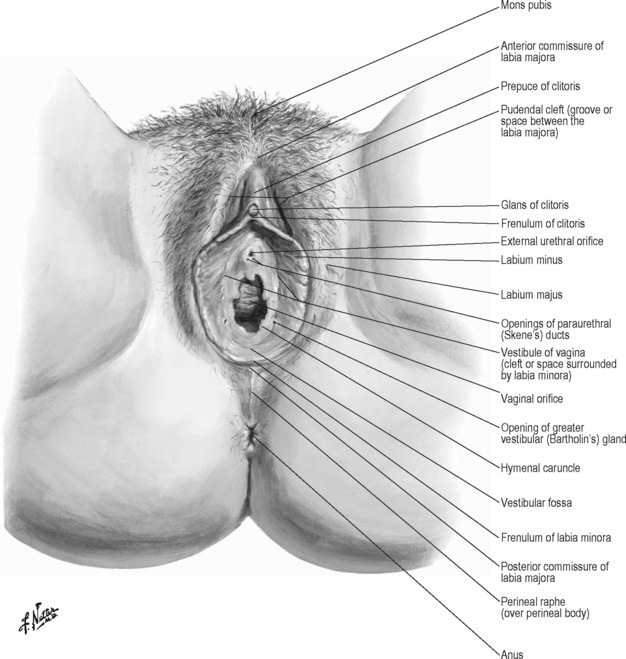

As the patient lies in the crook lying position the pubic bone is observed in the 12 o’clock position on the vertical clock and the perineal body is at 6 o’clock. The mons pubis is the area of skin overlying the pubic bone. Inferior to this is the anterior commissure of the labia majora; this is where the divide of the labia majora starts. The labia majora ends at the posterior commissure of the labia majora superior to the perineal body. Inferior to the anterior commissure of the labia majora is the area of tissue superior to the glans of the clitoris called the prepuce of the clitoris. Lateral here is the pudendal cleft which is the space between the labia majora. The frenulum of the clitoris is the area just below the clitoris. The labia minora start at the clitoris and extend down to the frenulum of the labia minora superior to the perineal body. The vestibule of the vagina is the space surrounded by the labia minora. Below the frenulum of the clitoris is the external urethral orifice and below this again is the vaginal orifice. Lateral to the vaginal orifice in the 5 o’clock and 7 o’clock positions are the openings of the Bartholin’s glands (Figure 13.3).

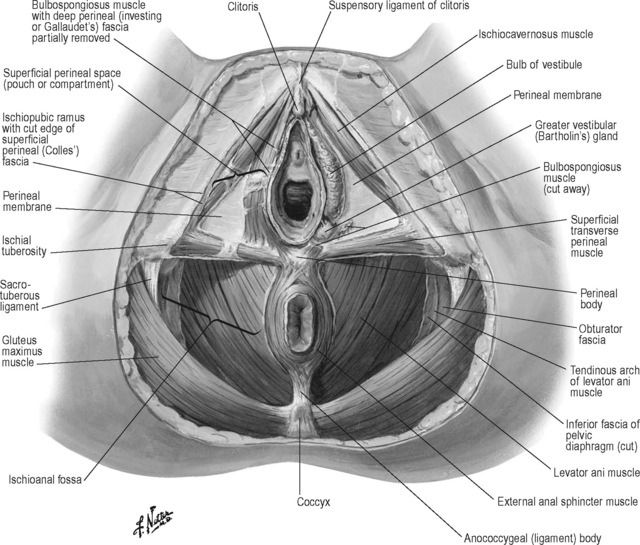

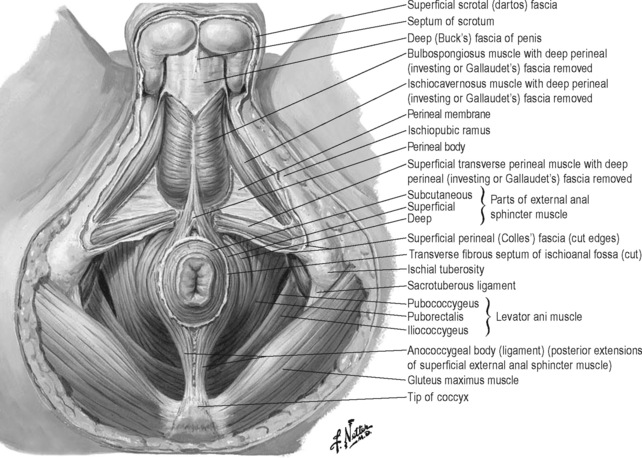

The perineal body is positioned between the posterior commissure of the labia majora and the anus; it forms the centre point of the perineum and lies deep to the external genitalia. Attaching to the perineal body centrally are the superficial transverse perineii muscles and they extend bilaterally to the ischial tuberosities. The ischiocavernosus muscles arise from the ischiopubic ramus and extend upwards to the crus of the clitoris. The bulbospongiosus muscles attach to the perineal body, the fibres run on either side of the vagina covering the superficial part of the vestibular bulb and vestibular glands and insert below the clitoris (Figure 13.4). Palpation of the bulbocavernosus and the transverse perineii is best performed by pincer palpation where the pad of the palpating finger is inserted just inside the vagina and met by the opposition of the thumb on the outside. The tissue is stretched or rolled between the finger and the thumb revealing the resting tone, tension, taut bands and trigger points. The ischiocavernosus is palpated against the ischiopubic ramus behind.

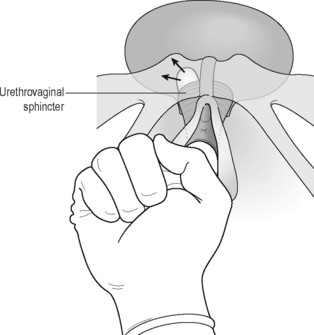

The deep perineal membrane extends from the ischiopubic ramus laterally to the vagina medially overlying what were previously referred to as the deep transverse perineal muscles but are the compressor urethrae muscle and the urethrovaginal sphincter muscles (DeLancey 1990). The urethrovaginal sphincter surrounds the vaginal wall and extends along the inferior pubic rami above the perineal membrane as the compressor urethrae. Superficial to these are the ischiocavernosus, bulbocavernosus and transversus perineii and the fascia superficial again to this layer is the superficial (Colles) fascia. The bulb of the vestibule is deep to the bulbospongiosus muscle and attaches to the deep perineal membrane. The perineal membrane is also referred to as the urogenital diaphragm (Herschorn 2004).

Practical anatomy on the vertical clock – Internal vaginal

The internal examination is started at the introitus with the pad of the finger palpating the perineal body, which is the central tendon of the superficial pelvic floor; resistance and length of the pelvic floor should be appreciated here. A short pelvic floor will be palpated where the dorsum of the finger just inside the vagina is held tight up against the pubic bone (Fitzgerald & Kotarinos 2003).

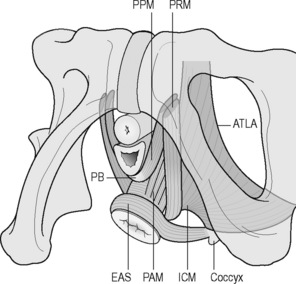

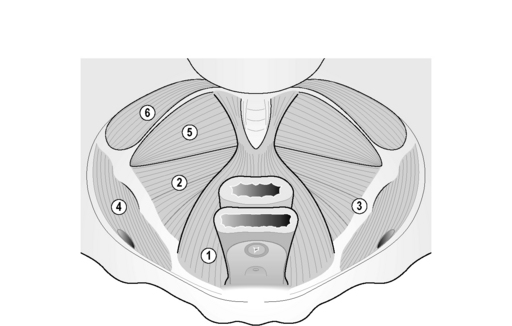

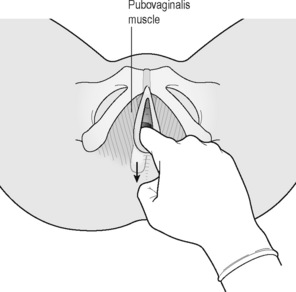

The anterior attachments of the levator ani muscle group are palpated on this plane by moving the palpating finger laterally to feel for resistance and attachment to the pubic bone. The most superficial part of the levator ani group is the puboperineal portion attaching from the pubic bone to the perineal body; the pubovaginalis muscle attaches from the pubic bone to the posterior vaginal wall and the puboanal portion inserts into the anal canal and skin (Figure 13.5). These muscles are part of the pubovisceralis muscle group, they were previously referred to as the pubococcygeus muscle but were renamed to reflect the orientation of the different parts of the muscle in the pelvic floor (Lawson 1974, Kearney et al. 2004). Now the pubococcygeus muscle refers distinctly to the muscle attaching from the pubic bone to the coccyx only. The puborectalis is distinct from the other pubovisceralis muscles as it attaches to the pubic bone and forms a sling behind the rectum and creates an angulation of the rectum whereas the other muscles elevate the anus perineal body and vagina (DeLancey & Ashton-Miller 2007).

Loss of attachment of the puborectalis will be palpated as bony end feel laterally on the pubic bone and high tone will be noted as thickened and resistant, often with acute pain at this point in the symptomatic patient. If the finger can be moved over the inferior pubic ramus without encountering any contractile tissue for 2–3 cm then this implies an avulsion injury to the puborectalis on that side. This may be the case in 15–30% of women who have given birth normally (Dietz 2009). This is compared from side to side. The palpating finger then tracks along the posterior vaginal wall evaluating resistance and this resistance can change from the vertical to the horizontal clocks as the pubovaginalis to the puborectalis muscles are palpated. The pubovaginalis or puborectalis muscles are short if the palpating finger is held up against the pubic bone. It may be difficult to stretch or lengthen the muscle and deep palpation may reveal a specific point of tension or a taut band within the muscle. There may be increased sensitivity in this localized taut band indicating the presence of a trigger point. On moving the finger slightly more posteriorly into the vagina, the rectovaginal fascia is palpated overlying the rectum, the rectum and its contents are palpated. Just lateral to the rectum, tone of the puborectalis is palpated, high tone will flex the palpating finger and there will be strong resistance on downward pressure.

The pad of the palpating finger is turned upwards towards the urethra. The anterior wall is covered by the pubocervical fascia and the urethra is palpated through this fascia. The pubocervical fascia extends from the symphysis pubis along the anterior vaginal wall to blend with the fascia that surrounds the cervix. The urethra is followed posteriorly behind the pubic bone up to the urethrovesical junction and finally the base of the bladder is palpated. Immediately in front of the cervix the base of the bladder rests on the vaginal wall (Brooks 2007). Descent of the anterior wall either low down or up higher is felt as a soft ‘bogginess’. The vesical neck should lie 2–3 cm above the insertion of the pubourethral ligaments and the inferior surface of the pubic bone (DeLancey 1990). The pubourethral ligaments form the periurethral connective tissue and attach to the white line of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis close to its pubic end (Standring 2008).

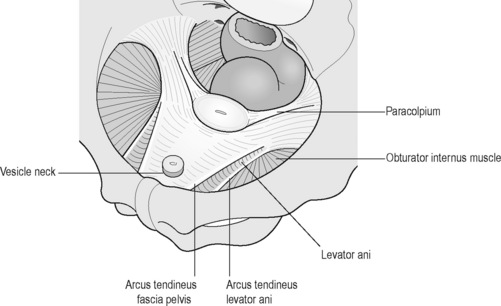

The urethra is palpated by a longitudinal or lateral stretch of the overlying tissue, sensation, resistance and painful points are evaluated. Posterior to and arising just lateral to the pubic symphysis is the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (ATFP). The ATFP corresponds to the lateral attachment of the anterior bladder wall to the pelvic side wall and is joined by fibres of the superficial fascia of the levator ani. Its connection to the pubis lies 1 cm above the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis and 1 cm lateral to the midline (DeLancey 1990). The anterior portion is palpable at its attachment to the pubic bone and posteriorly it becomes less well defined and more difficult to palpate as it broadens out towards its attachment to the ischial spine (Figure 13.6).

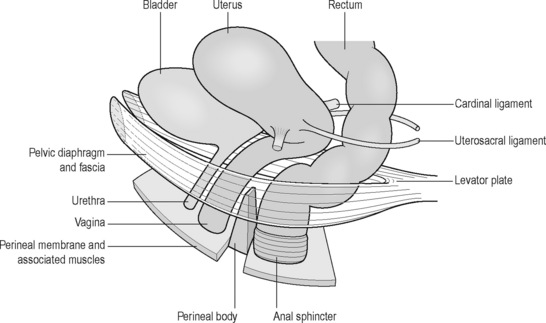

On palpation along the anterior wall of the vagina, the end point will be the anterior fornix. At this point the anterior wall is attached to the cervix of the uterus, the cervix is palpated and then the posterior fornix is palpated, depending on the position of the uterus, the posterior fornix may be difficult to palpate. The apex of the vagina is palpated and total vaginal length is noted. It is worth noting both position and the resistance of the uterus on palpation as clinical observation has shown this may change with treatment and can be retested. The paracolpium is the connective tissue surrounding the mid to upper vagina and uterus and fuses with the pelvic wall and fascia laterally. The cardinal ligaments extend from the lateral margins of the cervix and upper vagina and lateral pelvic walls, to an area expanding from the greater sciatic foramen to the piriformis and the lateral sacrum as far as the sacroiliac joints. The uterosacral ligaments are attached to the cervix and upper vagina posterolaterally and posteriorly to the fascia in front of the sacroiliac joints (Herschorn 2004). The paracolpium can be palpated but the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments are too deep to be palpated to their attachments. The apex of the vagina and uterus are held in place by the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments anchoring the pelvic viscera over the levator plate (Figure 13.7).

Practical anatomy on the horizontal clock – Internal vaginal

The examination so far has involved evaluation of the structures palpable in a circumferential and caudal to cranial direction. Now on examination of the deep pelvic floor the orientation changes in that the palpating finger examines across the posterior, lateral and posterolateral walls (Figure 13.2).

The palpating finger faces downwards towards the base of the spine and starts with palpation of the coccyx. The most posterior of the pelvic floor muscles is the ischiococcygeus attached from the coccyx to the ischial spine. Anterior to this is the iliococcygeus part of the levator ani group, a thin fan-shaped muscle extending from the tendinous arch of the levator ani (TALA) and with some fibres extending from the anus, to the last two segments of the coccyx (Figure 13.8). The fibres from both sides fuse and will form a raphe contributing to the anococcygeal ligament; this raphe is called the levator plate and provides shelf-like support to the organs. This is important for the configuration of the upper horizontal vaginal axis and support to the rectum and upper two-thirds of the vagina (Singh et al. 2001, Herschorn 2004).

The ischial spine is palpated as a bony point but the surrounding structures can have a taut end feel so it is not always easy to discriminate between bone and soft tissue. Anterior and inferior to the ischial spine is the pudendal nerve which can then be tracked anteriorly in Alcock’s canal (see Chapters 2.3 and 11.2). The obturator internus attaches to the TALA medially and the ilium laterally; it extends anteriorly to the pubic bone and posteriorly to the ischial spine. The belly of the obturator internus is palpated through the overlying obturator fascia; the obturator canal carrying the obturator nerve is palpated by tracking anteriorly towards the pubic bone.

The portion of the levator ani muscle attaching to the anal canal is named the puboanal muscle (Figure 13.8). The orientation here changes and the direction of stretch to determine resistance is towards the anus. The sphincter can be palpated vaginally by opposing the pad of the palpating finger overlying the sphincter and the thumb externally. Tension points can be successfully picked up using this method. A separate anal examination should also take place where indicated (see below).

The puboperineal and pubovaginalis portions of the levator ani have been described in the section on evaluation on the vertical plane; the puborectal and puboanal portions are described above. The pubococcygeal portion arises from the pubic bone and extends to its attachment at the coccyx; the term pubococcygeus can only properly be used to describe the few fibres that join bone to bone (Strobehn et al. 1996). It is palpated laterally to the puborectalis. The pubovisceralis muscle as described by Lawson (1974) is the correct term used to describe the levator ani muscle with its attachment primarily to soft tissue as well as to bone.

Practical anatomy of the male pelvic floor

Introduction

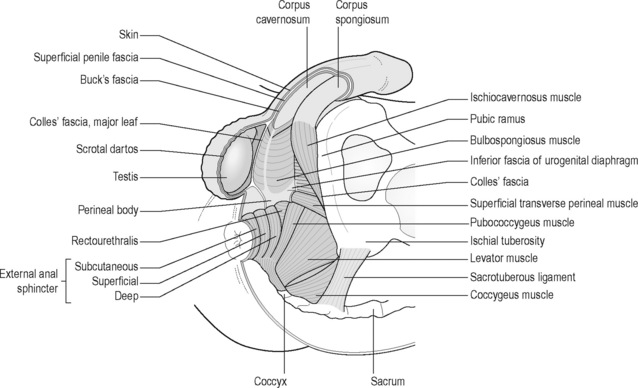

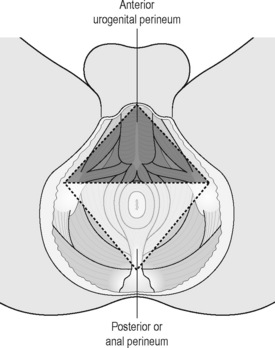

The male perineum has been described as fitting into two triangles: an anterior or urogenital perineum, formed by a line through the perineal body extending to the ischial tuberosities on either side and upwards to the symphysis pubis, and posterior perineal triangle formed by the base line through the perineal body and ischial tuberosities where the apex of the triangle is the coccyx (Figure 13.9). On most textbook anatomical views the anus and coccyx on this posterior triangle are depicted on exactly the same plane as the urogenital triangle; however, it can be observed clinically that the anus is slightly more posterior and the coccyx is even more posterior on the supporting surface with the patient in the crook lying position. The urogenital triangle can be useful when observing the structures on the perineum for orientation.

Figure 13.9 • Male perineum, urogenital triangle.

Reproduced from Anson, McVay (1984) Surgical Anatomy, sixth ed. WB Saunders

The vertical clock as described for the female pelvic floor is less practical here without the common access point anterior to the perineal body. Therefore the common base of the clock at 6 o’clock will be the anus with 12 o’clock as the pubic symphysis on the vertical clock and 12 o’clock as the coccyx on the horizontal clock, with the patient in supine crook lying position (see Figure 13.1). Structures accessed through the anus and rectum in a caudocranial direction circumferentially around the examining finger are described on the vertical clock; structures examined on the deep posterior and posterolateral wall are described on the horizontal clock.

Practical anatomy on the vertical clock – External perineal

On the urogenital triangle, the pubic symphysis is at the apex underlying the scrotum, which is lifted up for purposes of examination, and the perineal body is at the central point of the base of the triangle. Attached to the perineal body are the superficial transverse perineii muscles extending out to the ischial tuberosities laterally to the corners of the urogenital triangle. These corners are slightly below the central point of the perineal body. The bulbocavernosus attaches to the perineal body inferiorly and extends upwards inserting into the dorsum of the penis and the perineal membrane. The ischiocavernosus muscles arise from the ischiopubic rami laterally and cover the corpora cavernosa (Figure 13.10).

Practical anatomy on the vertical clock – Internal anal

The anal sphincter has an internal and an external component. The external anal sphincter surrounds the internal anal sphincter. The internal anal sphincter is a thickening of the inner circular smooth layer of the rectum. The external anal sphincter muscle has a subcutaneous, a superficial and a deep portion which are variable and often indistinct. The subcutaneous part attaches to the perineal body. The superficial part also attaches to the perineal body and to the coccyx as the anococcygeal raphe (Figure 13.11). At the posterior inflection of the rectum the deep sphincter blends with the puborectalis sling of the levator ani. Along the anal canal, posteriorly is the attachment of the puboanal portion of the levator ani muscle and fascia of the pelvic diaphragm. The corrugator cutis ani muscle situated around the anus is a thin layer of involuntary muscle fibre radiating from the orifice and blending with the skin. It raises the skin into ridges around the margins of the anus.

The pad of the examining finger palpates the full circumference of the sphincter, palpating at first downwards towards the coccyx and then facing upwards towards the pubic bone followed by laterally either side. Movement may be difficult where the sphincter is tight. It should be possible for the patient to be able to relax with the examining finger in place. Overactivity of the sphincter is when it remains difficult to move the examining finger even with the application of release techniques (see Chapter 11).

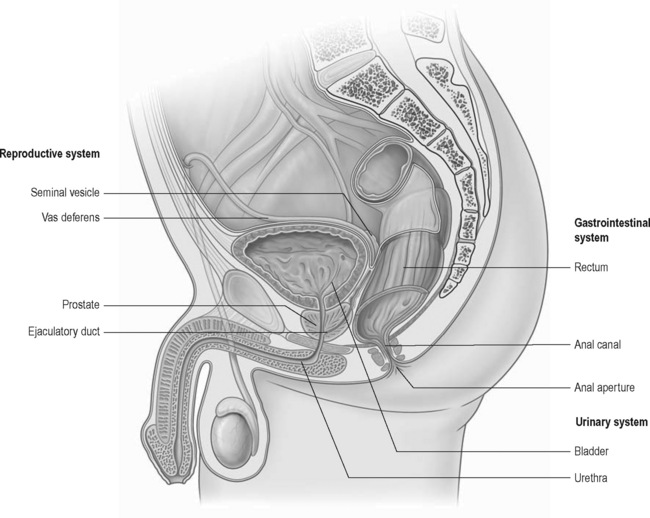

Practical anatomy on the vertical clock – Internal rectal

Once inside the sphincter the examination on the vertical clock continues. The pad of the palpating finger is turned upwards and the prostate is palpated (Figure 13.12). The prostate has anterior, posterior and lateral surfaces, it has a narrowed apex inferiorly and a broad base superiorly. The base is contiguous with the base of the bladder. It is a glandular and fibromuscular structure, 3 cm in length, 4 cm in width and 2 cm in depth (Brooks 2007). The pubic bone can be palpated below and on either side of the prostate. Deep to and traversing the length of the prostate is the urethra; inferiorly the apex is continuous with the sphincter urethrae muscle and the deep transverse perineal muscles.

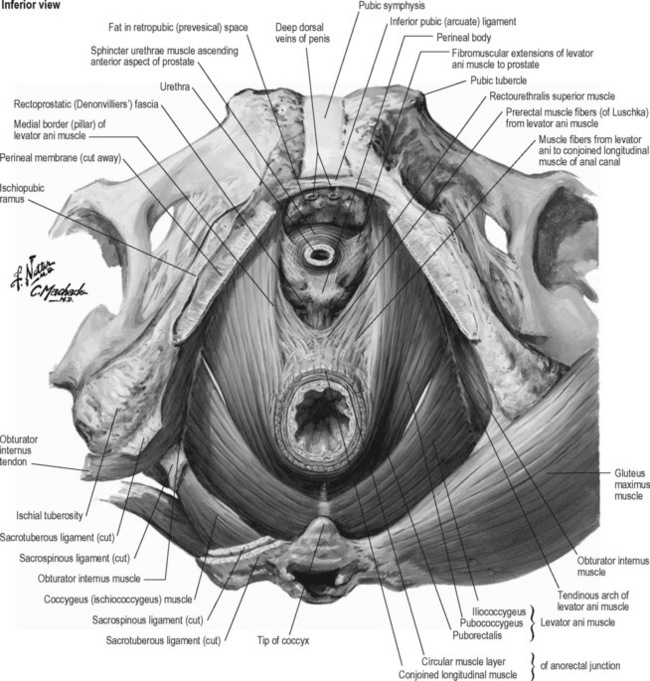

The urethra is 18–20 cm long and extends from the bladder neck through the prostate and the penile shaft to its meatus at the glans penis. It is divided into the proximal (sphincteric) portion and the distal (conduit) segment (Dorey 2002). The prostate and bladder base are palpated through the rectal fascia, the rectovesical space and rectovesical and rectoprostatic fascia. There is a further space between the bladder and the pubic bone called the retropubic (Retzius) space. From the rectum towards the prostate there are muscle fibres from the levator ani to the conjoined longitudinal muscle of the anal canal, prerectal muscle fibres from the levator ani muscle and the rectourethralis superior muscle. There are fibromuscular extensions of the levator ani muscle extending from the prostate up to the insertions of the levator ani on to the pubic bone.

Practical anatomy on the horizontal clock – Internal rectal

It is at the apex of the prostate that the anus will open out into the rectum as it extends 90° posteriorly. It is important that there is sufficient relaxation at the sphincter to be able to carry out this examination. The pad of the palpating finger faces down reaching posteriorly towards the examining surface till it comes in contact with the coccyx. The coccyx for purposes of description is at 12 o’clock on the horizontal clock. The ischiococcygeus muscle is palpated extending laterally to the ischial spine from the coccyx. The iliococcygeus muscle arises from the ischial spine and the tendinous arch of the levator ani (TALA) which can be felt all the way to the pubic bone anteriorly (Figure 13.13). The iliococcygeus inserts into the coccyx bone joining with the iliococcygeus from the other side forming the levator plate. Posteriorly the anococcygeal body or ligament is palpable. The pudendal nerve is palpated anteromedially to the ischial spine (see Chapters 2.3 and 11.2).

Direction-specific manual therapy of the pelvic floor

Introduction

Tension and trigger points are associated with chronic pelvic pain conditions and their treatment forms part of the multidisciplinary approach (Weiss 2001, Anderson et al. 2005, 2006, Srinivasan et al. 2007). The background and mechanism of trigger points are discussed in depth in Chapter 11. Trigger points can be treated successfully externally and internally and manual therapy is the first treatment of choice (Dommerholt et al. 2006). External treatment of the pelvic floor is described in Chapter 11. This section explores the release of trigger points and tension in the pelvic floor specifically using the concept of the direction of movement of the pelvic floor to maximize the effect.

The pelvic floor has a specific direction of activation: a contraction will squeeze the vagina, urethra and rectum closed against the pubic bone and lift the organs in a cephalic direction (Ashton-Miller & DeLancey 2007), but the direction of contraction will not always be cranioventral where dysfunction exists (Jones et al. 2006). If a pelvic floor contraction is normally cranioventral then release should normally be dorsocaudal. The levator ani will have a slightly different direction of activation depending on the part of the muscle and the fibre orientation, the puborectalis kinks the anorectal junction and will lift cranioventrally, the pubovaginalis, puboperinealis and puboanal muscles will elevate the perineal body and anus (Peschers & DeLancey 2008).

Part of the principle of treatment of a trigger point is to sufficiently elongate the muscle, producing a maximum palpable distinction between the normal tonus of the uninvolved fibres and increased tension of the taut band fibres. Optimal tension is usually about two-thirds of the muscle’s normal stretch range of motion but may be only one-third or less with very active trigger points (Travell & Simons 1999).

Release of muscle and fascia externally is also key in treatment of chronic pelvic pain disorders. These techniques are described separately in Chapter 11.

Techniques

The exact techniques can vary according to the clinician’s findings; however, the techniques used may be limited because of the reduced accessibility with single-digit palpation vaginally or rectally. Generally the palpation techniques described by Travell & Simons (1999) will cover all muscles in the pelvic floor: flat palpation, pincer palpation and deep palpation. These will generally be static compression techniques as transverse friction is not advisable in the deep pelvic floor as the tissue can be delicate and the condition is not visible.

• Flat palpation is where the finger tip slides the overlying fascia aside and palpates across the fibres to be examined.

• Pincer palpation is performed by grasping the muscle between the finger tip and thumb and pressing the fibres or rolling forwards and backwards to locate taut bands; these techniques will be for the superficial or more accessible tissue.

• Deep palpation is when intervening tissue overlies the muscle containing the trigger point and palpation through tissue is necessary. ‘Sufficient pressure on a trigger point always elicits at least withdrawal, wincing or vocalization by the patient’ (Travell & Simons 1999).

The amount of time spent on restricted tissue and the amount of pressure exerted will vary according to the sensitivity of the tissue. General treatment of central and attachment trigger points has been well documented by Chaitow & DeLany (2002) and the timing described by the same authors in integrated neuromuscular inhibition technique (Chaitow 1994) has been found by the author to be effective. They describe a pressure sufficient to activate the trigger point is maintained for 5–6 seconds followed by 2–3 seconds release and repeated for up to 2 minutes until the patient reports that the local or referred symptoms have reduced. Importantly the ischaemic pressure is stopped if there is an increase in pain or if the pain has ceased. This is followed in the original description by positional release techniques but can also be followed in the pelvic floor by direction-specific breathing techniques to maximize the release, and other breathing techniques as described in Chapter 7.

Transverse massage or longitudinal stretch massage can be used to lengthen the tissue (Hong et al. 1993). Massage of the pelvic floor can be performed rectally or vaginally; this was first described rectally by Thiele (1963). He recommended rubbing the fibres along their length, with a stripping motion from attachment at the pubic bone to insertion at the coccyx. Levator ani massage was also described by Grant et al. (1975) in successful treatment of patients with levator ani syndrome. Travell & Simons (1999) described stripping massage as a powerful tool in activation of accessible myofascial trigger points. Malbohan et al. (1989) described successful levator ani massage with a dorsal movement of the coccyx to stretch the levator ani in treatment of low back pain attributed to coccygeal spasm.

Manual techniques on the vertical plane

Travell & Simons (1993) have stated that none of the superficial muscles are likely to be identifiable unless they have taut bands lying parallel to the direction of the muscle fibres. Furthermore they are likely to present as single muscle syndromes with pain referral locally and into the urethra, perineum and the vulva in women and the penis in men, whereas levator ani and coccygeus are more likely to exhibit multiple muscle involvement.

Anterior to posterior levator ani stretch

This anterior to posterior stretch has already been described by Weiss (2001) in the female pelvic floor (Figure 13.14). The distal phalynx of the palpating finger rests on the posterior vaginal wall from the perineal body to approximately 2 cm inside. The puboperineal muscle and the pubovaginal muscles are stretched posteriorly and taut bands or points of referral are identified and treated by ischaemic pressure until the tension eases or the referral decreases. The attachments are followed laterally up to the pubic bone and the pressure becomes more specific laterally to evaluate the insertions on either side. Attachment trigger points result from sustained increased tension of the muscle fibres to their bony insertion. This sustained tension can produce swelling and tenderness described as enthesopathy where the muscle fibres attach (Travell & Simons 1999). This is an important point for evaluation and resistance may be high at these points especially with pelvic floor overactivity.

Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis

The ATFP are tensile structures corresponding in the female to the lateral attachment of the anterior bladder wall to the pelvic side wall and the base of a sulcus between the pelvic side wall, the prostate and bladder in the male (Brooks 2007). They are palpable as well-defined fibrous bands at the origin near the pubic bone becoming less well defined as they pass posteriorly to insert into the ischial spine fusing with the endopelvic fascia and merging with the levator ani (Ashton-Miller & DeLancey 2007) (Figure 13.6).

The ATFP connection to the pubis lies 1 cm above the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis and 1 cm lateral to the midline (DeLancey 1990); it is palpated with the pad of the finger along the undersurface of the pubic bone on the anterior vaginal wall and the anterior rectal wall in the male. Contact is soon lost as the fascia extends posteriorly superiorly alongside the base of the bladder in the direction of the ischial spine. This structure is distinguished from the attachment of the tendinous arch of the levator ani described in the next section as it extends across from the vertical to the horizontal plane.

Damage to this fascia and its attachments has been implicated in cystocele, urethrocele and stress urinary incontinence in females, so its presence and presentation will be variable (Brooks 2007).

Urethra

The urethra is palpated on the vertical plane with the pad of the palpating finger facing upwards from the urethral meatus cranially to the urethrovesical junction posterior to the pubic bone and as far as the bladder base. The overlying connective tissue will be variable in sensitivity and mobility; quality of movement can be tested by gliding the pad of the finger either caudocranially along the urethra posterior to the pubic bone or transversely moving the urethra laterally. These lateral distraction techniques have been described by Weiss (2001) (Figure 13.15) and under connective tissue manipulation in Chapter 11.2.

In the male the urethra traverses the prostate centrally and is therefore only palpable through the prostate in this prostatic portion on internal examination. Prostatic massage has been described as therapeutic in the treatment of urologic chronic pelvic pain (Anderson et al. 2009).

External anal sphincter

Treatment through the external anal sphincter is commenced by asking the patient to bear down as the gelled examining finger is introduced. If the sphincter is tight, as it may be with chronic pelvic pain or defecation disorders, then extreme care should be taken and other external manual techniques may be necessary before proceeding. Treatment techniques are commenced as the pad of the finger faces the supporting surface in crook lying position, the sphincter eases out as the finger is introduced at first 1–2 cm and then further to 3–4 cm incorporating the puborectalis muscles (Dorey 2002). If sufficient range of movement is available the finger can be turned the full circumference of the sphincter turning towards the right and towards the left and feeling for resistance and differences throughout the higher portion and the lower portion of the sphincter, then pressing into areas of resistance.

A further technique to treat the external anal sphincter is using pincer palpation with the thumb externally over the sphincter opposing the index finger internally resting over the vaginal tissue on the sphincter. This way the entire sphincter can be palpated for any tension and mobilized accordingly. In the male this pincer palpation is also possible through the anus but only segmental mobilization is possible between finger and thumb (see Figures 13.5 and 13.11).

Manual techniques crossing over vertical to horizontal plane

Puborectalis

Puborectalis is accessed either vaginally (as a first choice) or rectally in women and rectally in men. It is stretched from the attachment at the pubic bone anteriorly to behind the rectum posteriorly and deep in the direction of a point anterior to the coccyx (Figure 13.16). Deep in the pelvic floor, the puborectalis spans from just posterior to the anus supporting the rectum, to just anterior to the coccyx. The entire muscle is evaluated for trigger points, areas of referral and taut bands. When symptomatic, the patient may report a strong feeling of faecal urge or a shooting pain up into the rectum or pain referring elsewhere inside the vagina in the female or perineum and penis in the male. The patient may also describe pain referral into the coccyx. The terms proctalgia or proctalgia fugax are often used as an umbrella term to describe the symptoms of referred pain with elicitation of a puborectalis trigger point; proctalgia by definition is a disorder of the internal anal sphincter. Right and left are evaluated and compared. The downward stretch will feel very resistant on the overactive pelvic floor and it may take a few sessions to unfold a specific referring trigger point. If there is loss of attachment, the surrounding and contralateral muscle may hypertrophied as it is overloaded (Dietz 2009). Deep palpation will be needed in the puborectalis muscle.

Tendinous arch of levator ani

The TALA inserts anteriorly into the pubic bone and posteriorly to the ischial spine as does the ATFP but the orientation is different. The TALA is palpated more laterally and superiorly on the pubic bone than the ATFP. Contact can be maintained throughout as it is followed laterally and posteriorly to the ischial spine. Palpation is started with the finger pad facing upwards on the vertical plane and laterally along the pubic bone until the thin tendinous attachment is identified, then the finger will need to turn facing downwards, laterally towards the side wall of the pelvis and posteriorly as it follows the arch backwards to its attachment at the ischial spine (see Figure 13.8).

Manual techniques on the horizontal plane

Iliococcygeus and the levator plate

The iliococcygeus is described as the shelf support muscle of the pelvic floor; it is a thin fan-shaped muscle extending from the tendinous arch of the levator ani to the coccyx. The fibres are more horizontal centrally as they insert into the coccyx and form part of the anococcygeal raphe (Strohbehn et al. 1996). The raphe between the anus and coccyx is the levator plate; it is formed by the fusion of the iliococcygeus and the posterior fibres of the pubococcygeus (Herschorn 2004). The point of palpation to identify tension in the belly of the muscle is, on the horizontal clock, at 10 o’clock on the right and 2 o’clock on the left in a posterolateral direction towards the supporting surface (see section on anatomy). When the iliococcygeus muscle has been overloaded there is no ‘give’ in this direction and deep pressure reveals a taut, fibrous muscle (see Box 13.1, Figure 13.17).

Box 13.1 Note on iliococcygeus specific to female anatomy

The iliococcygeus muscle is not thought to have a role in the cranioventral activation of the pelvic floor because of the orientation of the fibres. It is injured in childbirth considerably less often than the pubovisceral portion of the levator ani (DeLancey et al. 2003). It was reported in one study that only three out of 32 birth injuries were to iliococcygeus; the rest were to the pubovisceral portion of the muscle (DeLancey et al. 2003). A contractile iliococcygeus will elevate the pad of the palpating finger uniform with the rest of the levator ani. When inhibited a levator ani contraction will flex the palpating finger and the iliococcygeus does not stay in contact with the pad of the palpating finger. It has been reported that surrounding muscles are overloaded by trigger-pointed muscles or by loss of attachment (Weiss 2001, DeLancey & Ashton-Miller 2007, Dietz 2009). It could therefore be that inhibition of the iliococcygeus indirectly affects the cranioventral activation of the other levator ani muscles because of its proximity to them and its attachments laterally and posteriorly pulling the muscles in this posterolateral direction. The significance of this is that if the shelf support role of the iliococcygeus is lost then the load of the organs on the pelvic floor will be greater, causing further stress inhibition and trigger points on the pelvic floor muscles.

Downward and lateral pressure is exerted into the belly of the muscle and the fibres are stretched towards the supporting surface. The muscle can be quite taut throughout and it can take time and significant pressure to pick out symptomatic taut bands and trigger points. The description by Wilson (1936) of the muscle fibres being ‘matted together’ works well here. During treatment, the patient often describes a feeling of a hard bar on the supporting surface under the pelvis. There may be pain referral to the hip area or to the coccyx and this area can also reproduce some rectal symptoms. It can be acutely painful but frees up over the course of a session of manual therapy and activation can be felt to change where the cranioventral activation of the pelvic floor improves (see Box 13.1).

Obturator internus

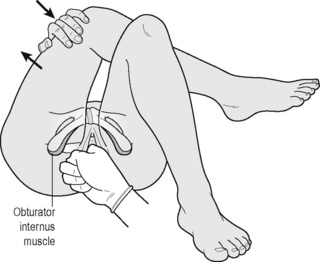

When palpating the left side of the patient the therapist will be in a left laterally side bent position with the right elbow high in order to access these left lateral structures. Ideally the therapist will have developed ambidextrous skills to be able to treat the patient’s left side with the therapist’s left hand. Alternatively for the right-handed therapist the patient could be positioned in left side lying to access the left side. The obturator internus is successfully accessed for treatment externally (see Chapter 11.1).

Weiss (2001) described palpation of the obturator internus with simultaneous stretch of the muscle in lateral hip rotation (see Figure 13.18).

Direction-specific breathing release

Introduction

In recent years there has been much literature describing the effects and importance of breathing on the musculoskeletal system; these are investigated in detail in Chapter 9. The involvement of the abdomen has also been well documented and is now an integral part of any physiotherapy treatment for chronic pelvic pain (Slocumb 1984, Fitzgerald et al. 2009, Kotarinos et al. 2009, Montenegro et al. 2009).

If a patient is in acute pain then internal manual techniques will be difficult to tolerate and it will be prudent to spend time learning breathing release and abdominal release techniques to counteract tension. Studies have looked at the interaction of the pelvic floor with breathing (O’Sullivan et al. 2002, O’Sullivan & Beales 2007, Pool Goodzward 2004, Hodges et al. 2007) and the descent of the pelvic floor has been described as a normal consequence of inspiration (Talasz et al, 2010). Paradoxical relaxation has been described in Chapter 12, and its success has been documented (Anderson et al. 2005, 2006). The technique described below has been developed by the author in its current form to help with direction-specific release.

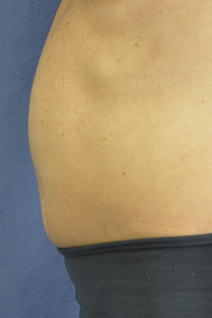

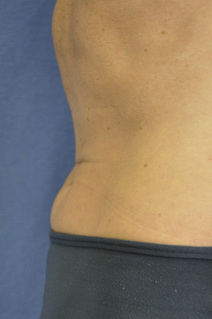

The current technique involves inspiration, diaphragmatic descent and simultaneous release of the abdomen in order to produce a direction-specific release of the pelvic floor. This release is passive in the pelvic floor and should happen as a consequence of the correctly performed in-breath; however, the ability of the patient to maximally release the posterior pelvic floor helps the quality of the release. The ‘cylinder’ is explained and an image portrayed of a taut elastic band between the diaphragm and the pelvic floor (Figure 13.19). The taut band represents the tension within the muscles and fascia between the diaphragm and the pelvic floor. As the patient breathes in the diaphragm descends and the abdomen fills out, the elastic band is slackened allowing a release of the pelvic floor (Figure 13.20). This release is dependent on the abdomen being maximally released at the same time as it expands. Any tension at all in the abdomen will stop the release happening in the pelvic floor. The patient learns to visualize the direction of release of the pelvic floor and how to use their in-breath to control it. This is described to the patient as ‘sniff, flop and drop’ and is broken down for teaching purposes as follows.

Sniff, flop and drop technique

Abdominal palpation

The patient lies supine with legs out straight so that the abdominal muscles are somewhat on stretch. The patient learns to identify their points of tension through the abdomen from the ribs to the pubic bone but the upper abdomen is the key point in allowing the diaphragm to descend. The upper triangle formed by the lower ribs up to the xiphisternum is the area that should be focused on at first to allow optimal descent of the diaphragm. The patient is shown self-palpation using deep perpendicular pressure through the rectus abdominis, the oblique muscles and abdominal fascia. They may also work with a manual therapist to achieve better release. In addition the use of a therapeutic ‘spikey’ ball or tennis ball at home may be helpful as the patient lies on the ball starting off supported on the elbows, to identify a tension point, and then lowering gradually onto the ball and wriggling on it to identify specific areas of tension. The patient can then breathe with emphasis on breathing out, while relaxing as the pressure from the ball eases the local tension. This technique should be performed starting with any tension on the lower right abdomen and working around to the upper right, upper left and lower left to follow the direction of the colon into the bowel. The patient should not spend more than 10 seconds on each point before rolling slightly off onto another adjoining point (Figure 13.21).

Sniff

If the in-breath has been performed correctly, with the abdomen letting go, then the exhalation that follows will be short and soft, as if all the air had ‘disappeared’. This can be compared with the short and soft out-breath, used to clean a pair of spectacles (Figures 13.22 and 13.23).

Flop

The patient is taught to identify their stomach-holding pattern and to learn where their flexion/holding line may be. The patient also learns how to let go from the ribs down to the pubic bone or just flop the stomach out. Again this is assisted by palpation and manual therapy. The flop may be more productive in side lying as gravity assists and the patient has the image of letting go into the supporting surface. This can also be worked on in forward kneeling, e.g. resting arms on a gym ball or in four-point kneeling. It can be counterintuitive to flop up against gravity (Figures 13.24 and 13.25).

Drop

The patient learns to release the pelvic floor in an action that is called a drop. The patient is taught that the pelvic floor releases backwards, visualization and demonstration with diagrams helps the individual to feel a release in the direction of the coccyx. It is explained that the pelvic floor has some tone even at rest and it is this resting tone that is being changed with the release. The release can be described as an opening of the sphincter muscle or a lengthening of the U-shaped sling muscle backwards towards the supporting surface or coccyx. The patient can also think of opening or flaring the coccyx backwards towards the supporting surface (Figures 13.26 and 13.27).

Pelvic floor contraction

When the release of the pelvic floor has been practised then the patient can progress to contraction for balance and strengthening and to use the contraction for better quality of release according to the principle of post-isometric release (see below). The instruction for a pelvic floor contraction is to pull in the back passage as if to stop oneself from passing wind, and to continue lifting upwards and forwards towards the pubic bone. This instruction has been shown to be successful in producing a cranioventral contraction (Jones et al. 2006, Lovegrove-Jones 2010). Although this sounds to be specific to the back passage, it does cross the pelvic floor from back to front and this is explained to the patient as they are shown the diagrams (see Figures 13.26 and 13.27).

Transversus abdominis and pelvic floor contraction

The pelvic floor contraction can be facilitated by transversus abdominis (TrA), as this method has been shown to facilitate a contraction of the levator ani muscles (Sapsford et al. 2001, Jones et al. 2006, Junginger et al. 2010). It may not always be a good idea to use the TrA muscle as this may encourage negative muscle activity patterns. This should be evaluated by the therapist in assessment of the pelvis and trunk. The following instruction for contraction is based on the assumption of correct activation of the TrA muscle, with no bracing of the upper abdomen, hardening of the stomach on palpation, or drawing of the ribs downwards. The patient is instructed without breathing to slowly and gently draw the lower stomach in, as if away from the zip of the trousers, or drawing the navel towards the spine (see Figures 13.28 and 13.29). The pelvic floor may start contracting on its own at this stage. The back passage is then drawn upwards and forwards towards the pubic bone.

Home programme

The patient can also be encouraged to stretch their pelvic floor muscles themselves at home. It is suggested that while sitting on the toilet, the right thumb or index finger could be inserted in order to stretch the left levator ani backwards towards the coccyx, or the left thumb or index finger may be inserted to stretch the right levator ani backwards. Accessible trigger points can be self-treated in this way. Some patients will take to this idea and others will not. An alternative is to use an instrument which can be introduced through the vagina or the back passage and used to maintain pressure on the trigger point. Examples of two such devices are the wand developed by Wise & Anderson (2008) (which is described and illustrated in Chapter 12) and the EZ Magic angled probe available at www.icrelief.com.

The patient must also learn to not carry tension in the affected muscles throughout the day. Techniques to address this have been described by Wise & Anderson (2008).

Further techniques to maximize release

How exactly proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) works continues to be investigated and remains inconclusive (Chalmers 2004, Sharman et al. 2006). There are various hypotheses regarding the mechanisms of action of post-isometric relaxation; however, it is likely to involve both neurological and circulatory influences (Fryer & Fossum 2009). Clinically it can be observed that if a patient works on a maximal contraction into end of range and reinforces for example 5 times, the maximal release afterwards is even more effective.

The ‘sniff, flop and drop’ technique makes use of the ‘quick stretch’ theory described in proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF). The stretch stimulus has been defined as ‘an increased state of responsiveness to cortical stimulation that exists when a muscle is placed in an elongated position’ (Saliba et al. 1993). The stretch reflex is facilitated by a rapid elongation of the muscle that stimulates the muscle spindle fibres to fire resulting in a reflex contraction. This reflex response produces a short-lived contraction, where volitional control then takes over. Earlier in this section it was suggested that a quicker inhalation with a greater volume of air is more effective in releasing the pelvic floor than a slower in-breath with a slower pelvic floor release. It may be that this technique follows the principles of PNF.

Anderson R.U., Wise D., Sawyer T., Chan C. Integration of myofascial trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training in treatment of chronic pelvic pain in men. J. Urol.. 2005;174(1):155-160.

Anderson R.U., Wise D., Sawyer T., Chan C. Sexual dysfunction in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: Improvement after trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training. J. Urol.. 2006;176(4):1534-1539.

Anderson R.U., Sawyer T., Wise D., et al. Painful myofascial trigger points and pain sites in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J. Urol.. 2009;182:2753-2758.

Anson B.J., McVay C.B. Surgical anatomy. sixth ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1984:893.

Ashton-Miller J.A., DeLancey J.O.L. Functional anatomy of the female pelvic floor. Bo K., Berghmans B., Morkved S., Van Kampfen M., editors, Evidence Based Physical Therapy for the Pelvic Floor. 2007:25.

Brooks J. Anatomy of the lower urinary tract and male genetalia. Wein A., Kavoussi L., Nivick A., et al, editors, Campbell-Walsh Urology. ninth ed. 2007:61. 65

Brooks J.D., Chao W.M., Kerr J. Male pelvic anatomy reconstructed from the visible human data set. J. Urol.. 1998;159:868-872.

Chaitow L. Integrated neuromuscular inhibition technique. Br. J. Osteopathy. 1994;13(1):17-20.

Chaitow L., DeLany J. Summary of modalities. In: Clinical Application of Neuromuscular Techniques. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:201. 208

Chalmers G. Re-examination of the possible role of Golgi tendon organ and muscle spindle reflexes in proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation muscle stretching. Sports Biomech.. 2004;3(1):159-183.

DeLancey J.O.L. Anatomy and physiology of urinary continence. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol.. 33(2), 1990.

DeLancey J.O., Kearney R., Chou Q., et al. The appearance of levator ani muscle abnormalities in magnetic resonance images after vaginal delivery. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2003;101:46-53.

DeLancey J.O.L., Ashton-Miller J.A. MRI of intact and injured female pelvic floor muscles. Evidence Based Physical Therapy. 2007:94.

Dietz H.P. Pelvic floor assessment. Fetal Maternal Med. Rev.. 2009;20(1):49-66.

Dommerholt J., Bron C., Franssen J.L.M. Myofascial trigger points: an evidence informed review. J. Man. Manip. Ther.. 14(4), 2006. 2003–221

Dorey G. Anatomy and physiology of the male lower urinary tract. Conservative treatment of male urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction. 2002:8.

Fitzgerald M.P., Kotarinos R. Rehabilitation of the short pelvic floor.1: Background and patient evaluation. Int. Urogynecol. J.. 2003;14:261-268.

Fitzgerald M.P., Anderson R.U., Potts J., et al. Randomised multicenter feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy for the treatment of urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes. J. Urol.. 2009;182:570-580.

Fryer G., Fossum C. Muscle energy techniques. In: Fernández-de-las-Peñas C., Arendt-Nielsen L., Gerwin R.D., editors. Tension-type and cervicogenic headache: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Boston: Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2009.

Grant S.R., Salvati E.P., Rubin R.J. Levator syndrome: An analysis of 316 cases. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1975;18:161-163.

Haslam J., Laycock J. Therapeutic Management of Incontinence and Pelvic Pain: Pelvic Organ Disorders. second revised ed. London: Springer-Verlag; 2007.

Herschorn S. Female pelvic floor anatomy: The pelvic floor, supporting structures and pelvic organs. Rev. Urol.. 2004;6(Suppl. 5):S2-S10.

Herschorn S., Carr L.K. Campbell’s Urology 1092–1139. 2002.

Hodges P.W., Sapsford R., Pegel L.H.M. Postural and respiratory functions of the pelvic floor muscles. Neurourol. Urodyn.. 2007;26(3):362-371.

Hong C.Z., Chen Y.C., Pon C.H., Yu J. Immediate effects of various physical medicine modalities on pain threshold of an active myofascial trigger point. J. Musculoskeletal Pain. 1993;1(1):35-53.

Jones R.C., Peng Q., Shishido K., Constantinou C.E. 2D ultrasound imaging and motion tracking of pelvic floor muscle activity during abdominal manoeuvres in stress urinary incontinent women. Neurourol. Urodyn.. 2006;25(6):596-597.

Kearney R., Sawhney R., Delancey J.O. Levator ani muscle anatomy evaluated by origin-insertion pairs. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2004;104:168-173.

Kotarinos R. Physical findings in patients with urologic chronic pelvic pain findings. Neurourology and Urodynamics Proceedings of ICS. 2009:264.

Lawson J. Pelvic anatomy. l. Pelvic floor muscles. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl.. 1974;54:244-252.

Laycock J., Jerwood D. Pelvic floor muscle assessment: The PERFECT scheme. Physiotherapy. 2001;87(12):631-642.

Lovegrove Jones R.C. Dynamic Evaluation of Female Pelvic Floor Muscle Function Using 2D Ultrasound and Image Processing Methods. University of Southampton, Faculty of Medicine, Health and Life Sciences; 2010. PhD thesis

Malbohan I.M., Mojisova L., Tichy M. The role of coccygeal spasm in low back pain. J. Man. Med.. 1989;4:140-141.

Montenegro L.L.S., Gomide L.B., Mateus-Vasconcelos E.L., et al. Abdominal myofascial pain syndrome must be considered in the differential diagnosis of chronic pelvic pain. Eur. J. Obstet Gynecol Reprod. Biol.. 2009;147:21-24.

O’Sullivan P., Beales D. Changes in pelvic floor and diaphragm kinematics and respiratory patterns in subjects with sacroiliac joint pain following a motor learning intervention: A case series. Man. Ther.. 2007;12(3):209-218.

O’Sullivan P.B., Beales D.J., Beetham J.A. Altered motor control strategies with sacroiliac joint pain during the ASLR test. Spine. 2002;27(1):E1-E8.

Peschers U.M., DeLancey J.O.L. Laycock J., Haslam J., editors, Therapeutic management of incontinence and pelvic pain. 2008:9-20.

Pool-Goudzwaard A. Contribution of pelvic floor muscles to stiffness of the pelvic ring. Clin. Biomech.. 2004;19(6):564-571.

Saliba V., Johnson G.S., Wardlaw C. Rational Manual Therapies. In: Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation. Williams & Williams; 1993:249. Ch 11

Sapsford R.R., Hodges P.W., Richardson C.A., Cooper D.H., Markwell S.J., Jull G.A. Co-activation of the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles during voluntary exercises. Neurourol. Urodyn.. 2001;20(1):31-42.

Sharman M.J., Cresswell A.G., Riek S. Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching: mechanisms and clinical implications. Sports Med.. 2006;36(11):929-939.

Singh K., Reid W., Berger L. Assessment and grading of pelvic organ prolapse by use of dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2001;185:71-77.

Slocumb J. Neurological factors in chronic pelvic pain: Trigger points and the abdominal pelvic pain syndrome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.. 1984;149:536.

Srinivasan A.K., Kaye J.D., Moldwin R. Myofascial dysfunction associated with chronic pelvic floor pain: management strategies. Curr. Pain Headache Rep.. 2007;11(5):359-364.

Standring S. The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. fortieth ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier: Abdomen & Pelvis; 2008. Section 8

Strohbehn K., Ellis J., Strohbehn J., DeLancey J.O. Magnetic resonance imaging of the levator ani with anatomic correlation. Obstet. Gynecol.. 1996;87:277-285.

Talasz H., Kofler M., Kalchschmid Pretterklieber M., Lechleitner M. Breathing with the pelvic floor? Correlation of pelvic floor muscle function and expiratory flows in healthy young nulliparous women. Int. Urogynecol. J.. 2010;21(4):475-481.

Thiele G.H. Coccydynia: cause and treatment. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1963;6:422-436.

Travell J., Simons D. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The trigger point manual, vol 2: The lower extremities. 1993:117. 119, 122, 126

Travell J., Simons D. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The trigger point manual, vol 1: The upper half of body. 1999:11-93.

Weiss J. Pelvic floor myofascial trigger points: manual therapy for interstitial cystitis and the urgency-frequency syndromes. J. Urol.. 2001;166:2226-2231.

Whelan M. Laycock J., Haslam J., editors, Therapeutic management of incontinence and pelvic pain. 2008:60-61.

Wilson T.S. Manipulative treatment of subacute and chronic fibrositis. Br. Med. J.. 1936;1:298-302.

Wise D., Anderson R. A Headache in the Pelvis, fifth ed. National Center for Pelvic Pain; 2008.