Chapter 27 Provision of anaesthesia in difficult situations and the developing world

• lack of continuous electricity supply

• lack of continuous supply of oxygen and nitrous oxide

• difficulty with storage of drugs and equipment

• difficulty in transport and supply of drugs and equipment

• lack of maintenance of equipment

Where possible, on grounds of safety, patients should be transferred to medical facilities capable of providing the appropriate level of care. For example, electroconvulsive therapy for the psychiatric patient with severe aortic stenosis and depression would be better managed (from their cardiac status) in the operating suite of the main hospital rather than in a room off the psychiatric ward. Non-essential surgery should not be undertaken at the site of a major disaster or on the battlefield, and the use of local, regional or sedative techniques should be considered where appropriate.

Difficult situations within hospitals

Sites away from the operating theatres often have anaesthetic equipment that is used only occasionally. Piped oxygen and suction facilities may be absent. The equipment in such areas must be maintained and checked adequately, with basic monitoring meeting the standard recommended by the Association of Anaesthetists.1 Since January 2003, all anaesthetic machines in use in the UK must be incapable of delivering a hypoxic mixture. There must be immediate access to resuscitation equipment and drugs, and a means of summoning additional assistance (i.e. telephone or intercom). The anaesthetist and their assistant should have sufficient experience and be familiar with both the environment and the equipment.

Radiotherapy units

• Intense ionizing radiation requiring patient isolation from the medical attendants

• Closed circuit television or glass-liquid-glass window to view patient causing colour and image distortion

• Multiple frequent treatments over a few weeks

• Radiotherapy applicators may obstruct access to the patient’s head.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)2

• Intense magnetic field with the ability to cause equipment made of ferromagnetic material to be attracted at projectile velocity into the scanner. There is, however, a rapid decrease in field strength with distance

• Electrical inductance – potential for thermal injury from electrical conducting leads

• Electromagnetic interference leading to equipment malfunction (e.g. in syringe drivers) or artefact (e.g. altered ST-T region on ECG, from electrical currents induced by aortic blood flow in a magnetic field, rendering ischaemia detection difficult)

• Noise from vibration of switched gradient coils makes audible alarms inappropriate and necessitates ear protection

• Theoretical risk of hypoxia if quenching of the super-conducting magnets of cryogenic gasses (usually helium) occurs. Quenching may occur as a fault condition or be initiated for emergency shutdown of the magnet, and should be safe if gasses are appropriately vented to the outside.

These factors pose risks to patients and potential occupational hazards to staff. Patients and staff must be screened before access is granted to an MRI scanner, to exclude ferromagnetic implants, such as aneurysm clips or pacemakers.2 Anaesthetic equipment taken into the vicinity of the MRI scanner must be MR-compatible.

Remote anaesthesia

• TIVA may be employed using long infusion lines on pumps which must be able to cope with the high resistance to flow caused by the increased length. This usually means setting to maximum the pressure limit for sensing an occlusion.

• Whilst sedation may be sufficient for some patients, the airway may need to be established with a supraglottic airway device or tracheal tube.

• Intermittent positive pressure ventilation through a long coaxial breathing system such as a 9.6–10 m Bain circuit and Nuffield Penlon series 200 ventilator, has been shown to provide safe anaesthesia.3 With this system, there is an increase in the static compliance in proportion to the length of the tubing. This is caused by expansion of the breathing hose and compression of the volume of gas during positive pressure ventilation and will result in a lower tidal volume being delivered than is set on the ventilator although this may be mitigated by the tidal volume supplementation from the fresh gas flow. Capnography is essential. In children, if a Newton valve is used, the ventilator becomes a pressure generator, and the increased resistance and compliance of the long system results in the pressure delivered being significantly less than that selected (23% less with a 10 kg child). This compares to a 6–11% reduction when using a long rubber Ayre’s T-piece.4

• The capnography signal is delayed due to the length of the sampling line but provides a guide for adjustment of the tidal volume.

Interhospital transfers

• Communication between transferring and receiving teams and the ambulance service is essential. It is imperative that everyone concerned knows the current condition of the patient, the indication for transfer and the exact destination. It is also the responsibility of the referring team to arrange a suitably qualified medical escort.

• Documentation must stay with the patient. This includes the notes from the whole patient episode plus any additional relevant past notes, blood results and X-rays – either as hard copies or on CD. If blood has been cross-matched, it is worth transferring with the patient if the transfer is less than 4 hours because even though the receiving hospital will want to reissue it, this will be quicker than starting a cross-match from scratch.

• The patient should be stabilized as far as possible prior to transfer. The accompanying anaesthetist is unlikely to be familiar with the ambulance or what sort of equipment is immediately available and, therefore, should plan for all potential problems. In particular they should calculate the amount of oxygen that is going to be required and whether that has been catered for, the battery life on any infusion pumps should be adequate to allow for delays in traffic, etc., and spare infusions drawn up if necessary. Similarly, basic checks of equipment, such as availability of endotracheal tubes, working laryngoscopes, self-inflating resuscitation bag and IV cannulae, should not be omitted.

Developing countries

‘District hospital’-based anaesthesia

Draw-over anaesthesia

• means of giving supplemental oxygen (T-piece, length of tubing to use as oxygen reservoir and source of oxygen – i.e. cylinder or concentrator).

Draw-over apparatus

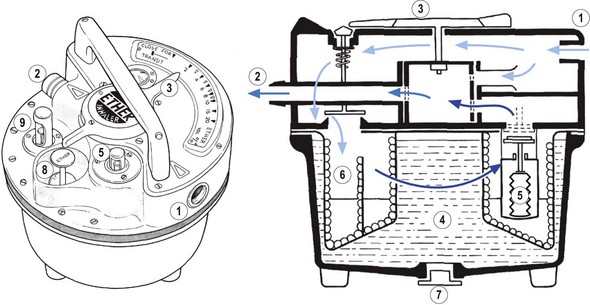

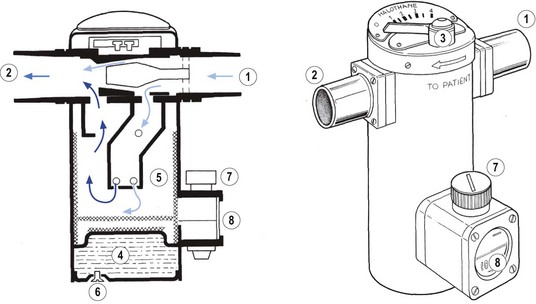

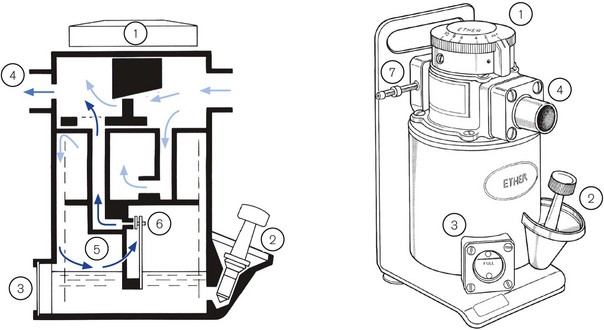

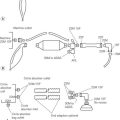

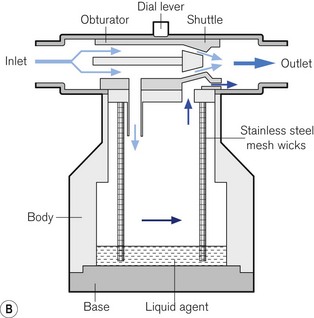

Several draw-over vaporizers are available, including the Epstein-Macintosh-Oxford (EMO) (Fig. 27.1), Oxford miniature vaporizer (OMV, described in greater detail below) (Fig. 27.2), the now discontinued Ohmeda PAC which is still in widespread use (Fig. 27.3) and the recently introduced Diamedica vaporizer5 (Fig. 27.4). The EMO and OMV vaporizers are elucidated further in Chapter 3.

Figure 27.4 Diamedica vaporizer. This is a 150 ml agent capacity draw-over vaporizer for isoflurane or halothane. The dial lever causes a shuttle to move against the stationary obturator, altering the size of the bypass route annulus. A calibration nut (not drawn) moves the obturator and is for factory or service technician use.

Photograph courtesy of Diamedica (UK) Ltd. Schematic redrawn from an original kindly supplied by Diamedica (UK) Ltd.

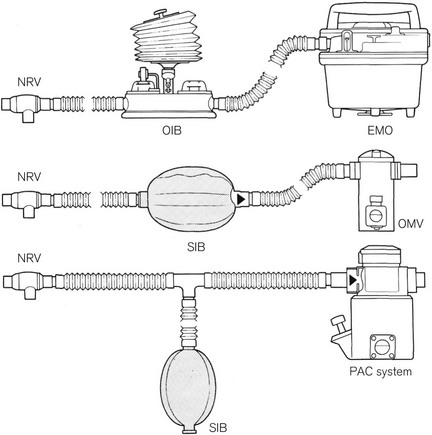

Practical equipment for safe anaesthesia can be provided by a combination of:

• the EMO vaporizer and/or the OMV (calibrated and used for halothane, isoflurane or trichloroethylene)

• a means of inflation such as a manual resuscitator or Oxford bellows

• a Ruben, Laerdal pattern or similar non-rebreathing valve (see Chapter 8)

Various arrangements of draw-over apparatus are shown in Fig. 27.5, and the working principles of the commonly available draw-over vaporizers are shown in Figs. 27.1–4.

These vaporizers, like the Triservice Apparatus, are not CE marked as the problems of poor calibration, lack of temperature compensation and inherent risk of spillage of agent into the breathing circuit are insurmountable. This causes difficulty in attempts to gain experience with the equipment in the modern hospital environment, where patients are entitled to receive the highest standard of available care. The issue of standards is in fact a significant and wide-ranging one. It is argued that the standards organizations, in being dominated by manufacturers, produce standards geared to driving sales of the latest technology to wealthy nations.6 Such equipment does not address the needs of developing nations and the standards inhibit ‘low technology’ developments.

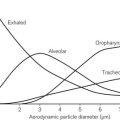

Supplemental oxygen

Medical oxygen may be available in cylinders, but these may not follow international standards of cylinder identification, and apparently full cylinders may be found to be empty. Industrial oxygen may be available, but be aware that there may be an increased level of impurities in such supplies. Up to 95% high-quality oxygen may be obtained from an oxygen concentrator (see Chapter 1). Oxygen concentrators are relatively maintenance-free, but require a source of electrical power to run a compressor and a switching device. A concentrator the size of a small domestic fridge will produce an inexhaustible supply of oxygen at the rate of up to 10 l min−1.

Ventilators suitable for developing countries

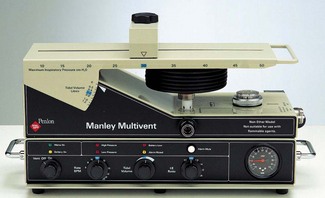

Manley Multivent ventilator

This ventilator was developed by the late Roger Manley, specifically for use in developing countries (Fig. 27.6).7 It differs from most other gas driven ventilators, in that the volume of gas required to drive the ventilator is only one-tenth of the patient’s minute volume. Furthermore, if the driving gas is oxygen it may be automatically collected and used to supplement the inspired oxygen concentration. Used in this way, set at a minute volume of 4 l min−1, an E size oxygen cylinder containing 680 L would drive the ventilator and supply 35% oxygen in air for a period of 28 h. The ventilator consists of a weighted beam, attached at one end to a fulcrum and at the other end to the top of the bellows. The beam is pushed upwards by the driving gas under a pressure of at least 140 KPa acting on a piston. When the set tidal volume is reached, the flow of driving gas is interrupted and the weight of the beam compresses the bellows, delivering the mixture of anaesthetic gasses to the patient. The economy of driving gas is achieved by the relative distances of the piston and the bellows to the fulcrum. Should the supply of pressurized gas fail completely, the bellows can be operated manually.

Combination anaesthetic equipment

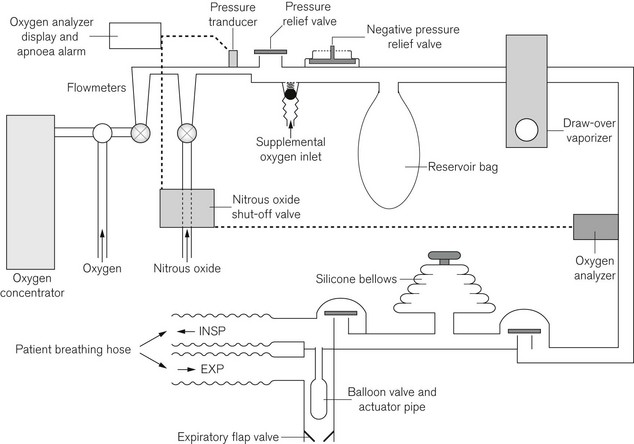

A number of ingenious machines incorporating an oxygen concentrator, oxygen cylinders, a ventilator, and vaporizers, which can be used in either draw-over or continuous flow mode, assembled on a mobile trolley, have been produced such as the prototype ‘Fentolator’ developed by Paul Fenton in Malawi.8 The advantages of such equipment in principle is that it is permanently assembled and available, aiming to be seen as the complete versatile anaesthetic machine. If monitoring equipment is available, this can be incorporated as well. Two fully developed examples of such combination equipment are the ‘Glostavent’ (Fig. 27.7) developed by Roger Eltringham in Gloucester, UK.9 based originally on the Manley Multivent Ventilator described above, and the Universal Anaesthesia Machine.

Figure 27.7 Glostavent Anaesthetic Machine, with Glostavent AP ventilator and oxygen concentrator.

Photograph courtesy of Diamedica (UK) Ltd.

Finally, the other essential piece of equipment is suction apparatus. In areas where electricity supply may be unreliable, it is advisable to have manual or foot-operated suction apparatus.

Universal Anaesthesia Machine (UAM)

At the time of writing, the very newly produced UAM (Fig. 27.8) is starting to undergo field evaluations, and represents the only CE marked anaesthesia machine designed with the needs of developing countries in mind. Developed by Paul Fenton and manufactured by OES Medical (Abingdon, UK), production has been made possible as a result of funding by the Nick Simons Foundation: a charitable organization dedicated to providing medical care in rural Nepal.

The UAM keeps the failsafe features of draw-over anaesthesia, but by removing the need for a non-rebreathing valve at the patient end of the breathing attachment allows use of modern lightweight coaxial or Y configured dual-limb breathing tubes, which also facilitate waste anaesthetic gas scavenging. The key feature in this is the balloon valve, incorporated into the machine, which occludes the expiratory limb of the breathing system through an actuator pipe that is pressurized from the breathing system to allow positive pressure ventilation (Fig. 27.9). A one way flap valve distal to the balloon occluder ensures unidirectional flow through the breathing system during spontaneous respiration.

Major accidents and disasters

The predominant anaesthetic contribution to a major disaster is resuscitation and stabilization prior to transfer to the receiving medical facility. Exceptionally, to aid extrication of casualties, amputation of trapped limbs may be required. This is best achieved using ketamine, either intravenously or intramuscularly. Equipment for intubation, self-inflating bag, fluid and cannulae for intravenous fluid resuscitation should be available. Oxygen and Entonox should be used cautiously in such conditions as they support and accelerate combustion of flammable materials, and whilst the latter has excellent analgesic properties, it may not be suitable in very cold conditions (see note Table 1.4) or in the presence of a head injury or pneumothorax.

The battlefield

• equipment must be air portable

• oxygen cylinders or concentrators are usually readily available

• cost constraints for drugs and equipment are minimal

• resupply is not usually a problem – unless supply lines are cut.

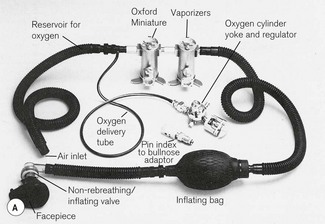

Triservice apparatus

The equipment in use at the moment by the British military medical services is the Triservice Anaesthetic Apparatus (Fig. 27.10).10,11 This consists of two modified OMVs connected via a self-inflating bag to a non-rebreathing valve and facemask or airway device. Supplemental oxygen may be delivered upstream of the vaporizers by a T-piece with a length of corrugated tubing acting as a reservoir. This complete apparatus, including an oxygen regulator and cylinder yoke, comes securely packed in foam within an air portable container, all weighing less than 25 kg, and can be safely dropped by parachute.

Figure 27.10 A. The Triservice apparatus. B.Triservice apparatus in use in push-over mode, Basra, Iraq (2007).

Photograph courtesy of Colonel S Jagdish L/RAMC, 33 Field Hospital.

Pneupac compPac ventilator

The Triservice apparatus may be used in spontaneously breathing patients, or IPPV may be instituted either using the self-inflating bag or by replacing the bag with a suitable ventilator. Originally the CapeTC50, a relatively portable ventilator consisting of a bellows expanded and contracted by an electric motor, was used. This has been replaced in British military use by the Pneupac compPAC ventilator (Fig. 27.11). This is a rugged, portable, gas-powered ventilator which can be driven from an external gas source (3–6 bar) or from its internal compressor. An integral rechargeable battery or external 24/28V DC supply drives the compressor and there is the facility for admixture of oxygen from a low pressure source.

Figure 27.11 Pneupac compPAC Ventilator, Smiths Medical, UK.

Photo courtesy of Smiths Medical International.

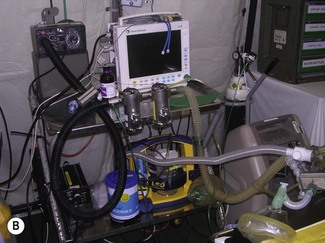

Joint operations with other national forces, which are the nature of current deployments of the British military, encourage the use of a more common platform of equipment where major medical facilities may be manned by non-UK personnel and where portability is not such a priority. More ‘conventional’ equipment may, therefore, be seen at a ‘role 3’ hospital (role 1 being closest to site of wounding, and role 4 being specialist services in the UK) such as in Camp Bastion in Helmand Province, Afghanistan (Fig. 27.12).

Equipment for other battlefield anaesthetic techniques

Total intravenous anaesthesia is also advocated for military anaesthesia as it can simplify equipment requirements. Ketamine/midazolam and propofol/alfentanil (either combination with vecuronium added for controlled ventilation) have been used very successfully, and requires little more than a self-inflating bag and oxygen source, together with an infusion bag (or syringe) with the mixed combination of drugs, and an infusion pump if available.12

Abnormal ambient pressures

Altitude

• Flowmeters. The reduction in gas density at altitude results in under-reading of variable orifice, constant differential pressure flowmeters. The error is about 20% at 3000 m. Under hyperbaric conditions, these flowmeters will over-read.13

• Pressure gauges. These are calibrated at sea-level and so over-read at altitude. The error is negligible, as the pressures measured are so much greater.

• Vaporizers. Saturated vapour pressure is a function of temperature, not ambient pressure. Hence, the concentration delivered by a vaporizer is inversely proportional to the ambient pressure as the vapour pressure takes up a higher proportion of the ambient pressure at altitude, and a lesser proportion under hyperbaric conditions. However, the partial pressure of the agent, which determines the clinical effect, remains constant. Therefore, when vaporizers are used at a given setting, the anaesthetic will be delivered at a constant potency or effect, regardless of concentration changes with altitude (or depth). A vaporizer set at 1% at sea level will deliver 1.7% at 4500 m, but the clinical effect will be unaltered.

• Gas analyzers and capnography. Gas analyzers measure the partial pressure of the gas under test but are calibrated in percentage at sea-level. They will, therefore, under-read at high altitude. Reduction of atmospheric pressure may also affect capnography in the following ways:14

• Venturi-type oxygen masks. These will entrain less air at altitude and so deliver higher concentrations of oxygen. A 35% mask will deliver approximately 41% oxygen at 3000 m.

• Ventilators. Volume or time-cycled ventilators may be preferable to pressure-cycled ventilators, but capnography and other monitoring will assist in adjusting ventilator settings under these conditions.

Hyperbaric chamber and anaesthetic equipment

A brief synopsis of some issues specific to high ambient pressure environment is given below (see also Chapter 7, Oxygen delivery at high or low atmospheric pressures):

• Gas diffusion into gasses or liquids causes bubbles on decompression. Rapid decompression with gas expansion may result in breakages of sealed, and particularly glass containers.

• Oxygen-rich environment under hyperbaric conditions increases the risk of fire; normally non-flammable materials may become flammable.

• During decompression, humidity increases, causing water condensation.

• The combination of increased water vapour and metallic walls and equipment increases the risk of electrocution and short circuits.

• Batteries – risk of bursting or leaking.

• Endotracheal tube cuffs should be liquid filled.

• Intravenous lines must be primed without air.

• Chest drains must be vented to chamber air through flutter valves (not bottles, as water seals may be problematic, particularly during rapid transition to different pressures).

• LCD monitor screens may crack or break due to gas bubbling out of solution during rapid decompression.

• Pressure transducers may malfunction.

• Simple minute volume divider ventilators may function better than other types of ventilators.

• Defibrillators are extremely hazardous due to the risks of electrocution and fire (see above). The metal floors and walls of the chamber mean that patient and operator are permanently earthed. Sparking may be disastrous under hyperbaric conditions in an atmosphere which may be contaminated with additional oxygen from the patient.

Monitoring

In remote situations where monitoring may be minimal by comparison with standards of practice in the developed world, there is no doubt that both the safety and quality of anaesthesia depends heavily upon the ability of anaesthetists to appropriately adapt techniques and equipment to the local environment and upon their skill and attention in responding rapidly to clinical signs.

Essential equipment to pack

• assorted connectors and adaptors

• basic airway equipment – self-inflating bag, face mask, Guedel airways, favourite supraglottic airways in a selection of sizes, laryngoscope (including spare batteries and bulbs)

• peripheral nerve stimulator and stimulating needles, batteries

• selection of emergency drugs, relaxants and local anaesthetics, preferably in plastic ampoules (a Home Office visa is required to take controlled drugs)

1 Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Recommendations for standards of monitoring during anaesthesia and recovery, 4th ed. 21 Portland Place, London W1B 1PY, AAGBI, 2007, http://www.aagbi.org/publications/guidelines.htm.

2 Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Provision of anaesthetic services in magnetic resonance units, 21 Portland Place, London W1B 1PY, AAGBI, 2002, http://www.aagbi.org/publications/guidelines.htm.

3 Sweeting CJ, Thomas PW, Sanders DJ. The long Bain breathing system: an investigation into the implications of remote ventilation. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:1183–1186.

4 Jackson E, Tan S, Yarwood G, Sury MRJ. Increasing the length of the expiratory limb of the Ayre’s T-piece: implications for remote mechanical ventilation in infants and children. Br J Anaesth. 1994;73:154–156.

5 English WA, Tully R, Muller GD, Eltringham RJJ. The Diamedica Draw-Over Vaporizer: a comparison of a new vaporizer with the Oxford Miniature Vaporizer. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:84–92.

6 Dobson M, Neighbour R. The International Standards Organisation is an obstacle to the development of appropriate anaesthetic equipment for the developing world. IET Seminar Digests. 2008;12213:3.

7 Manley R. A new ventilator for developing countries and difficult situations. World Anaesthesia Newsletter. 1991;5:10–11.

8 Eltringham RJ, Fan Qui W. The Glostavent – an anaesthetic machine for difficult situations. ITACCS. 2001;Spring/Summer:38–40.

9 Fenton PM. Inhalation anaesthesia in developing countries: the problems and a proposed solution – 3. Anaesthesia News, 2003;191:8–9. www.aagbi.org/anaesthesia_news_2003.html.

10 Houghton IT. The Triservice anaesthetic apparatus. Anaesthesia. 1981;36:1094–1108.

11 Adley R, Evans DHC, Mahoney PF, Riley B, Rodgers CR, Shanks T. The Gulf War: anaesthetic experience at 32 Field Hospital Department of Anaesthesia and Resuscitation. Anaesthesia. 1992;47:996–999.

12 Restall J, Tully AM, Ward PJ, Kidd AG. Total intravenous anaesthesia for military surgery. A technique using ketamine, midazolam and vecuronium. Anaesthesia. 1988;43:46–49.

13 McDowall DG. Anaesthesia in a pressure chamber. Anaesthesia. 1964;19:321–336.

14 Pattinson K, Myers S, Gardner-Thorpe C. Problems with capnography at altitude. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:69–72.

Dobson MB. Anaesthesia at the district hospital, 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

Ezi-Ashi TI, Papworth DP, Nunn JF. Inhalational anaesthesia in developing countries. The problems and a proposed solution. Anaesthesia. 1983;38:729–747.

Magee PT, Tooley M. The physics, clinical measurement and equipment of anaesthetic practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005.

McCormick BA, Eltringham RJ. Anaesthesia equipment for resource-poor environments. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(Suppl 1):54–60. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05299.x