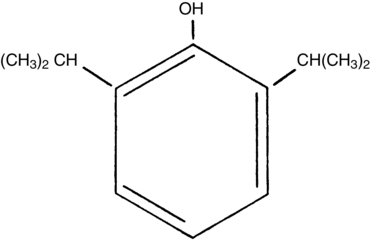

Propofol (2,6,-diisopropylphenol), an intravenously administered anesthetic agent, belongs to the family of sterically hindered phenols (Figure 72-1). Because propofol is water insoluble, it must be formulated in a 1% lipid emulsion, which is similar to that used in parenteral nutrition: it contains 10% soybean oil, 2.25% glycerol, and purified 1.2% egg phosphatide. The emulsion has not been reported to cause histamine release. Although patients who are allergic to egg whites have received propofol and have not experienced allergic reactions, propofol should probably not be administered to patients who have had an anaphylactic reaction to eggs.

Because thiopental is no longer available in the United States, propofol has become the most commonly used intravenously administered anesthetic induction agent; its advantages are a rapid onset and offset, a rapid redistribution such that little drug accumulates even with continuous infusions, and a very low rate of postoperative nausea and vomiting associated with its use. The antiemetic effects and clear emergence are most pronounced when anesthesia is maintained with an intravenously administered infusion of propofol. The antiemetic effects are so pronounced that 10 to 20 mg of propofol are occasionally administered in the postanesthetic care unit as rescue therapy for patients with postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Compared with the other intravenously administered anesthetic agents, propofol causes the most injection site pain and the most hypotension. The prevalence of pain on injection ranges from 10% to 50%, although the incidence of thrombophlebitis is low. Pain on injection can be attenuated by the intravenous use of local anesthetic agents and slow administration of the propofol into a large vein with rapidly running intravenous fluids.

Propofol infusion syndrome has been described in pediatric patients and in younger neurosurgical patients in the intensive care unit in whom propofol was infused at very high rates (>150 to 200 μg·kg−1·min−1) for hours to days; these patients developed profound metabolic acidosis, progressive bradyarrhythmias, cardiac arrest unresponsive to therapy, and death. The cause is unknown, though several mechanisms have been proposed.