15 Prolotherapy

A CAM Therapy for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain

Prolotherapy is an injection-based complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain. The historical roots of therapeutic intervention that may have similar underlying mechanisms of action, however, extend to antiquity. Hippocrates anecdotally described the use of hot wires to create scar tissue (sclerotherapy, an early name for prolotherapy) in cases of severe shoulder dislocation in soldiers. Prolotherapy injections have been used for approximately 100 years by physicians practicing both conventional and complementary medicine. Modern applications can be traced to the 1950s when prolotherapy injection protocols were formalized by George Hackett,1 a general surgeon in the United States based on his clinical experience of more than 30 years. Although techniques and injected solutions vary by condition, clinical severity, and practitioner preferences, a core principle of contemporary prolotherapy is that a relatively small volume of an irritant or sclerosing solution is injected at sites on painful ligament and tendon insertions, and in adjacent joint space over the course of several treatment sessions.1,2 Prolotherapy is becoming increasingly popular in the United States and internationally, and is actively used in clinical practice.3,4 Increased quantity and quality of the scientific literature supporting prolotherapy, internet reports, and the use of prolotherapy by prominent sports personalities all contribute to a growing visibility and interest among physicians and patients. A 1993 survey sent to osteopathic physicians estimated that 95 practitioners in the United States were estimated to have performed prolotherapy on approximately 450,000 patients. However, this survey likely underestimated the true number of practitioners dramatically because only 27% of surveys were returned.5 No formal survey has been done since 1993. The current number of practitioners actively practicing prolotherapy is not known but is likely several thousand in the United States based on attendance at CME conferences and physician listings on relevant websites. Prolotherapy has been assessed as a treatment for a wide variety of painful chronic musculoskeletal conditions that are refractory to “standard of care” therapies. Although anecdotal clinical success guides the use of prolotherapy for many conditions, clinical trial literature supporting evidence-based decision-making for the use of prolotherapy exists only for low back pain, several tendinopathies, and osteoarthritis.

Nomenclature

Nomenclature surrounding prolotherapy has evolved. This procedure, now known most commonly as prolotherapy, has been identified using names consistent with existing hypotheses and understanding of possible mechanisms of action. Nomenclature has reflected practitioners’ perceptions of prolotherapy’s therapeutic effects on tissue. Historically, this injection therapy was called “sclerotherapy” because early solutions were thought to be scar-forming. “Prolotherapy” is currently the most commonly used name, and is based on the presumed “proliferative” effects on chronically injured tissue. It has also been called “regenerative injection therapy” (RIT)2,6; some contemporary authors identify the therapy according to the injected solution.7 The precise mechanism of action of the various injectants is not known, but is likely to be multifactorial.

Professional Status

No single national medical organization acts as a supervisory, credentialing, or guideline-generating capacity for prolotherapy or its practitioners. The National Institutes of Health identifies prolotherapy as a CAM therapy. The NIH National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) has funded two ongoing clinical trials and two completed basic science studies on the mechanisms of prolotherapy.8,9 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Veteran’s Administration have reviewed the prolotherapy literature for low back pain and all musculoskeletal indications, respectively, and determined existing evidence to be inconclusive. Neither agency recommends third party compensation for prolotherapy. However, neither review included the most recent clinically positive studies or reviews in their evaluation.7,10–13 Private insurers are beginning to cover prolotherapy for selected indications and clinical circumstances; however, most patients pay “out-of-pocket”.

Prolotherapy Technique

Like contemporary Western medical therapies, CAM therapies often follow directly from a particular way of understanding the patient’s normal and pathologic conditions. For example, acupuncture relies on an ancient tradition of energy meridians and physiologic correlations that inform the specific procedures of needle placement to improve overall balance. Meditation relies on an understanding of interaction between mind and body to influence the body using mental processes. The same is true of prolotherapy. In his clinical text on the practice of prolotherapy, George Hackett laid out the foundations of treating musculoskeletal injuries using prolotherapy. He developed a diagnostic and treatment strategy familiar to those with a detailed knowledge of conventional Western understanding of the effects of local trauma, healing, and pain referral patterns. His diagnostic and therapeutic techniques, developed in the 1950s, could be viewed as holistic before the term gained popularity in contemporary medicine. Hackett interpretated chronic pain and referred pain symptoms such as numbness, tingling, and weakness, and alteration in proprioception, as originating, in part, from poorly healed ligaments and tendons. As such, he preceded by several decades the current change in the understanding of chronic tendon and ligament pain. Formerly thought to be primarily inflammatory in nature (“tendonitis), chronic tendon injury is now understood to be primarily a result of noninflammatory, degenerative tissue (tendinosis). Injection protocols for a particular body part tend to treat not just the specific injured structure, but also the surrounding structures, in an effort to increase the integrity of the area as a whole.

Clinical Vignette

Patient Description

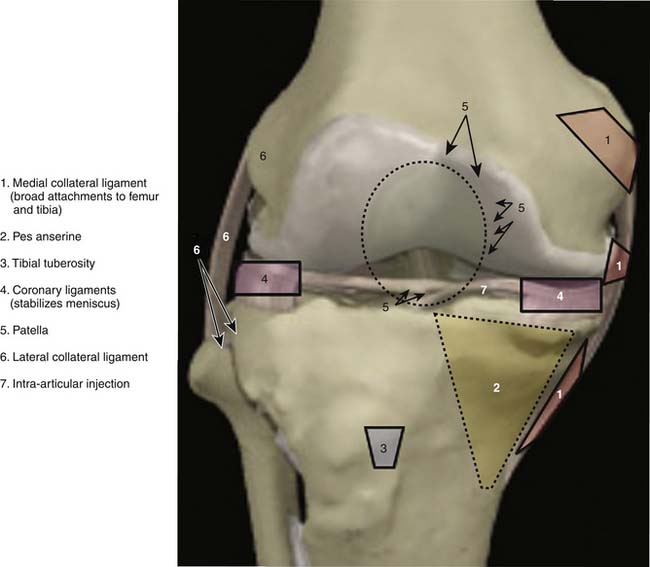

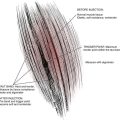

Anatomic marking and local anesthesia: The major superficial anatomic landmarks are palpated and marked with skin marker of choice (Fig. 15-1). Tender areas are injected with small intradermal skin wheals because this makes the deeper injections less painful. One percent buffered lidocaine is often used.

Injection of Ligamentous and Tendinous Attachments

Mechanism of Action

Injected solutions (“proliferants”) have historically been hypothesized to cause local irritation, with subsequent inflammation and tissue healing resulting in enlargement and strengthening of damaged ligamentous, tendinous, and intra-articular structures.14,15 These processes were thought to improve joint stability, biomechanics, function, and ultimately, to decrease pain.1,2

The mechanism of action for prolotherapy is not clearly understood and, until recently, it received little attention. Supported by pilot-level evidence, the three most commonly used prolotherapy solutions have been hypothesized to act via different pathways: hypertonic dextrose by osmotic rupture of local cells, phenol-glycerine-glucose (P2G) by local cellular irritation, and morrhuate sodium by chemotactic attraction of inflammatory mediators16 and sclerosing of pathologic neovascularity associated with tendinopathy.17,18 The potential of prolotherapy to stimulate release of growth factors favoring soft tissue healing has also been suggested as a possible mechanism.19,20

In vitro and animal model data have not fully corroborated these hypotheses. An inflammatory response in a rat knee ligament model has been reported for each solution, although this response was not significantly different from that caused by needle stick alone or saline injections.8 However, animal model data suggest a significant biologic effect of morrhuate sodium and dextrose solutions compared to controls. Rabbit medial collateral ligaments injected with morrhuate sodium were significantly stronger (31%), larger (47%), and thicker (28%), and had a larger collagen fiber diameter (56%) than saline-injected controls14; an increase in cell number, water content, ground substance amount, and a variety of inflammatory cell types were hypothesized to account for these changes.15 Rat patellar tendons injected with morrhuate sodium were able to withstand a mean maximal load of 136% (±28%)—significantly more than the uninjected control tendon.21 Interestingly, in the same study, tendons injected with saline control solution were significantly weaker than uninjected controls.21 Dextrose has been minimally assessed in animal models. Recent studies showed that injured medial collateral rat ligaments injected with 15% dextrose had a significantly larger cross-sectional area compared to both noninjured and injured saline-injected controls.22 P2G solution has received the least research attention; although it is in active clinical use, no animal or in vitro study has assessed P2G effect using an injury model. In research settings, most clinicians report using these solutions as single agents, although concentration of each one varies. In clinical practice, physicians sometimes mix prolotherapy solutions, or use solutions serially in a single injection session depending on experience and local practice patterns. The effect of varied concentrations or mixtures has not been assessed in basic science or clinical studies and no clinical trial has compared various solutions.

Clinical Evidence

Early Research

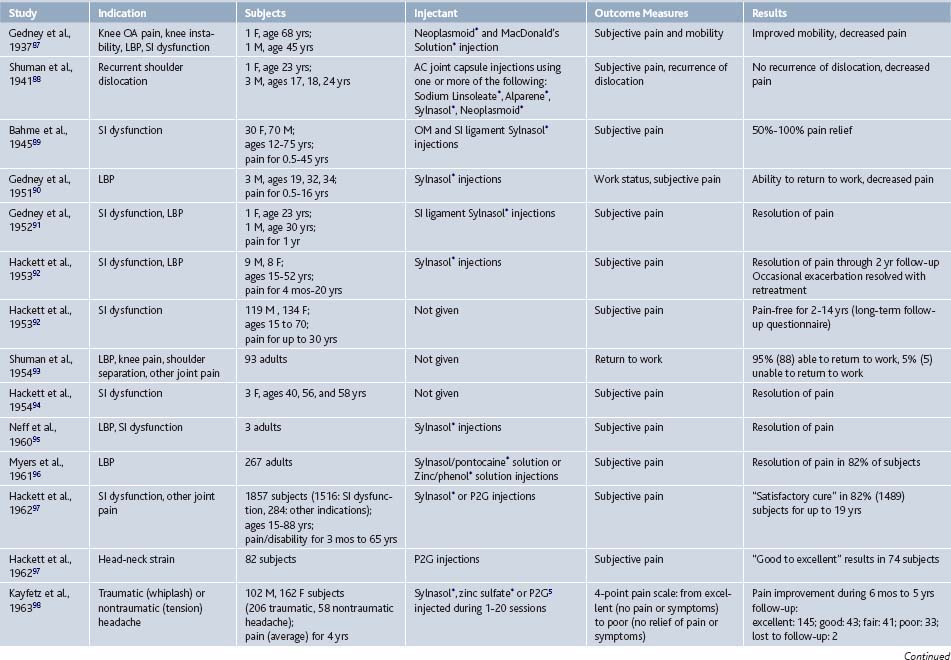

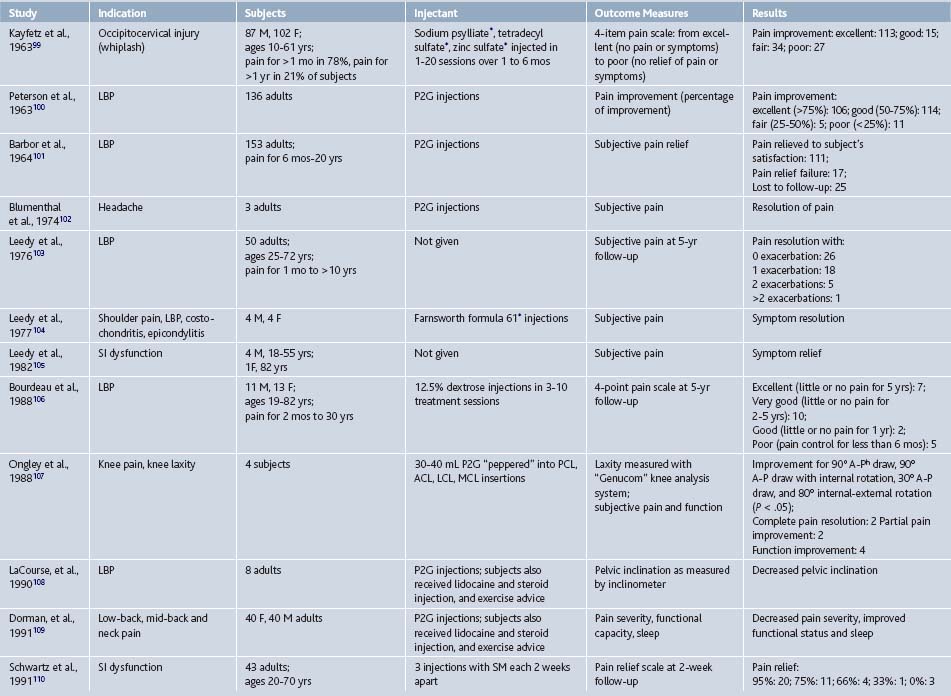

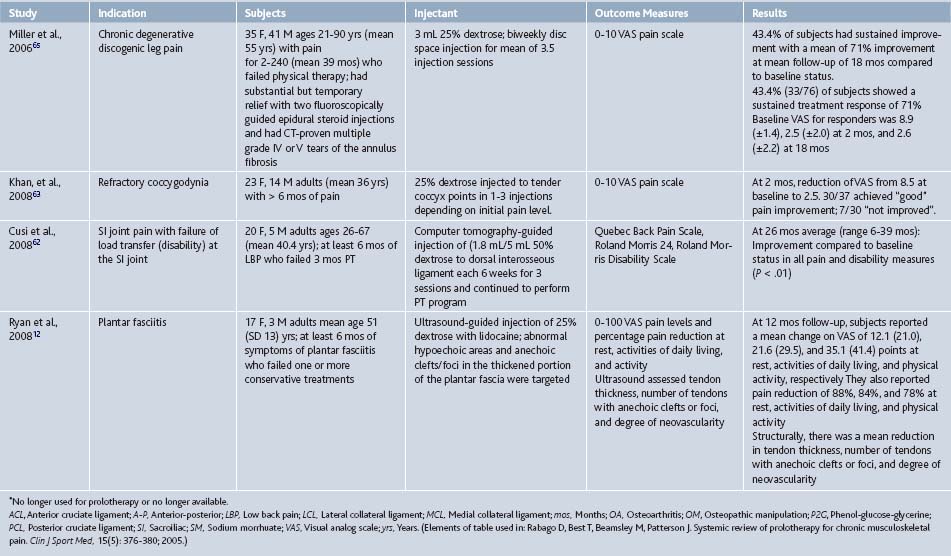

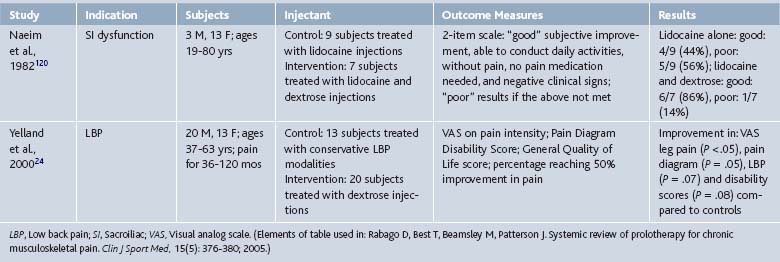

Since its inception, prolotherapy has been primarily performed outside of academia. Research has been primarily done by clinicians who perform prolotherapy themselves. This has lead to a pragmatic orientation of existing prolotherapy studies and a relative paucity of large, rigorous, clinical trials in spite of significant clinical activity. Although the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) did not appear until 1987, clinicians have enthusiastically reported the results of more modest, pilot-level nonrandomized clinical trials since the 1930s (Tables 15-1 and 15-2).

In 2005, our group reported the results of a systematic review of prolotherapy for all indications; we found 42 published reports of clincal prolotherapy trials since 1937.23 Thirty-six of the studies to date were case reports and case series that included 3928 patients aged 12 to 88 years. These uncontrolled studies provide the earliest and most clinically-oriented evidence for prolotherapy. Each study reported positive findings for patients with chronic, painful, refractory conditions. Report quality of the included studies varied widely; their internal methodologic strength was generally consistent with publication date. The older case studies documented several injectants and methods that are no longer in use. Contemporary solutions were noted to start with P2G in the 1960s, dextrose in the 1980s, and morrhuate sodium in the early 1990s. The case reports and case series highlighted the fact that, over time, prolotherapy has been used and studied for a continually growing set of clinical indications. These case studies have also been used as pilots to develop new assessment techniques that could help elucidate pathophysiology of the condition in question7 and test methodology for future, more robust randomized trials.24 In general, while lacking control groups and randomization, these pragmatic studies25 had the advantage of assessing effectiveness of prolotherapy in “real life settings” that patients encounter, including the prolotherapist’s ability to select the patient and to individually tailor the injection protocol. Most of the subjects (72%, 2691 of 3741) assessed in the early literature were treated for low back pain. However, other indications assessed by these early studies included knee osteoarthritis, shoulder dislocation, neck strain, costochondritis, lateral epicondylosis and other tendinopathies, and fibromyalgia (see Tables 15-1 and 15-2).

Contemporary Research

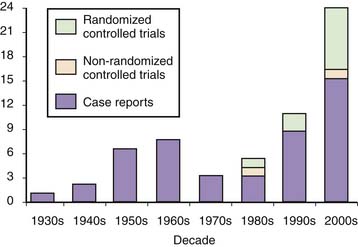

Research on prolotherapy and its clinical effects has accelerated, and the number and methodologic quality of studies assessing prolotherapy have increased dramatically since the mid-1980s (Fig. 15-3).

Figure 15-3 Number of published clinical studies on prolotherapy since 1937.

(Bar graph from: Rabago D, Slattengren A, Zgierska A. Prolotherapy in primary care practice. Primary Care, 37(1); 69-80; 2010.)

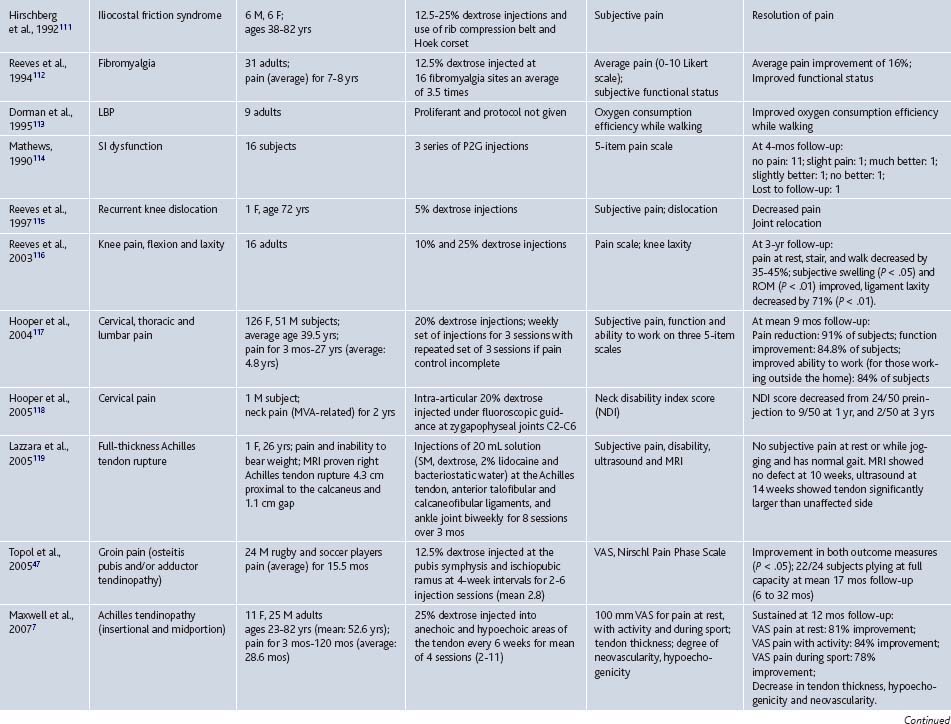

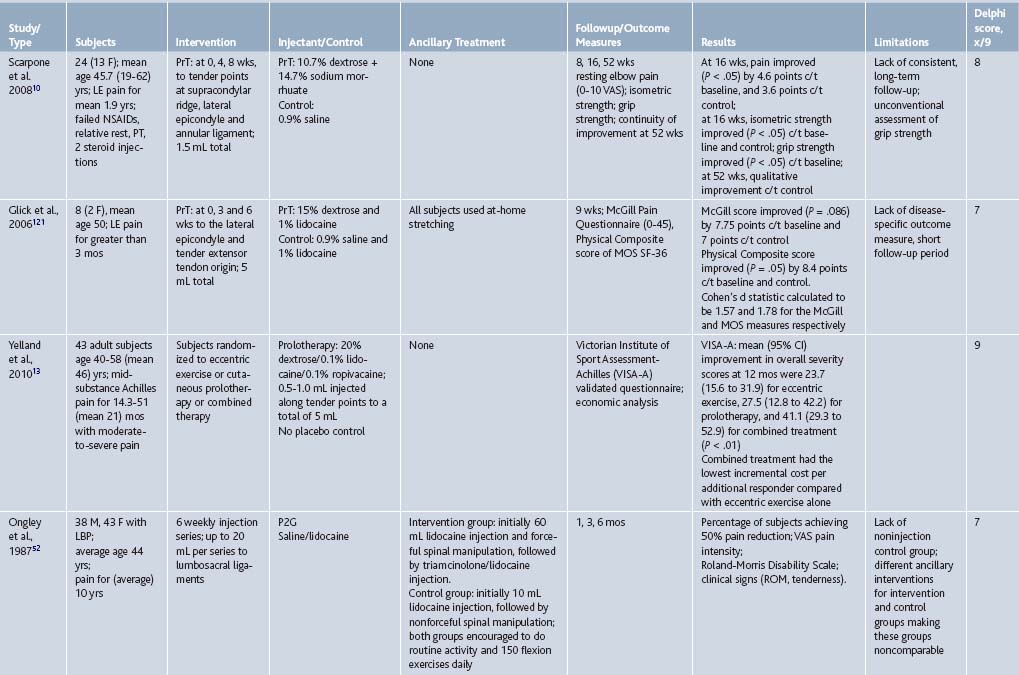

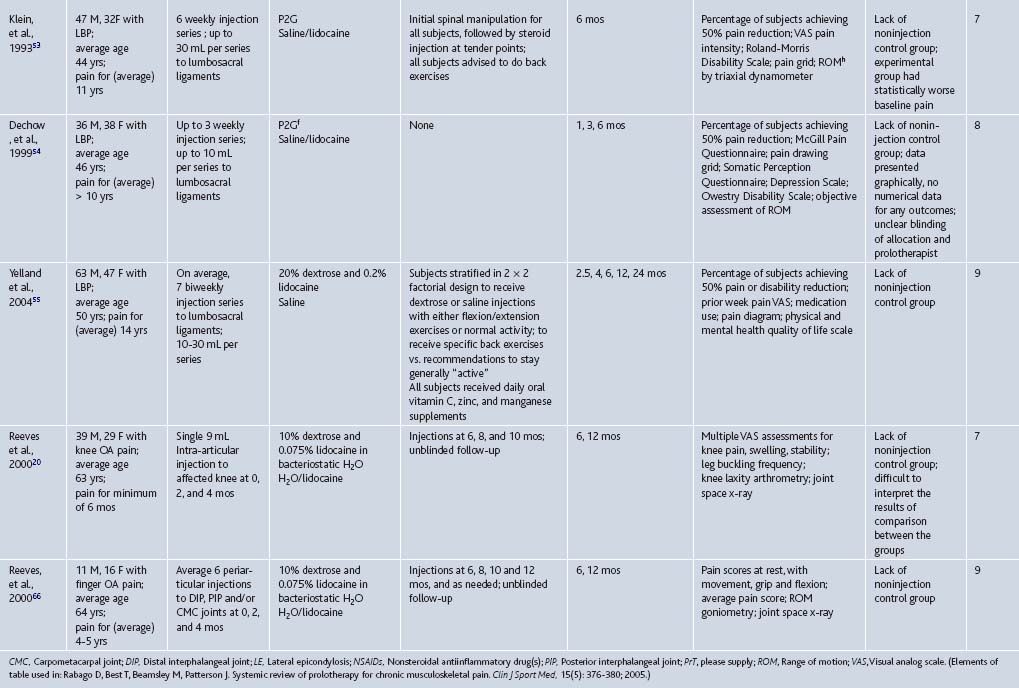

To date, prolotherapy has been evaluated using moderate-to-strong assessment techniques and study designs as a treatment for low back pain, osteoarthritis, and several tendinopathies; each condition is a significant cause of pain and disability, and is often refractory to best standard-of-care therapies. The societal impact of these conditions will likely increase in the coming years because the severity and prevalence of each condition is age related. Because the United States population is aging, finding new effective therapies for these conditions can have an impact on individual patient care and overall public health. If effective, the import of nonsurgical interventions such as prolotherapy will also grow. The following section gives an integrated description of higher quality studies assessing prolotherapy for these clinical indications, presented in an order of descending strength of evidence; RCTs are described first (see Table 15-3), and scored using the Delphi scoring system.26 A summary table follows that assigns a formal level of evidence grade for prolotherapy for each condition (Table 15-4).

Table 15-3 Randomized Controlled Trials Assessing Prolotherapy for Tendinopathy, Low Back Pain, and Osteoarthritis

Table 15-4 Strength of Evidence for Prolotherapy as a Treatment for Chronic Musculoskeletal Conditions: Low Back Pain (LBP), Osteoarthritis (OA), and Tendinopathy

| Key Clinical Recommendation on Prolotherapy | Evidence Rating | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Nonspecific LBP: may be effective; conflicting results in several RCTs | B | 52, 53, 54, 55 |

| Sacroiliac joint dysfunction: may be effective in patients with documented failure of load transfer (disability) at the sacroiliac joint | B | 62 |

| Coccygodynia: may be effective based on prospective case series | B | 63 |

| Lateral epicondylosis: likely effective based on strong positive data in these small RCTs | A | 10 |

| Achilles tendinopathy: may be effective based on high quality prospective case series | B | 7,13 |

| Plantar fasciitis: may be effective, based on high-quality prospective case series | B | 12 |

RCTs, Randomized controlled trials.

Tendinopathies

The strongest data supporting the efficacy of prolotherapy for any musculoskeletal condition, compared to control injections, is for chronic, painful overuse tendon conditions that were formerly called “tendonitis” and are now more correctly termed tendinosis or tendinopathy to reflect existing, underlying pathophysiology.27 Tendinopathies are common reasons why patients present to primary care providers and various medical specialists.28,29 Tendinopathies are sometimes discussed as a group because the current understanding of over-use tendinopathies identifies them as sharing underlying non-inflammatory pathology, resulting from a repetitive motion or overuse injury, and associated with painful degenerative tissue. Histopathology of tendon biopsies in patients undergoing surgery for painful tendinopathy reveals collagen separation,30 thin, frayed, and fragile tendon fibrils, separated from each other lengthwise and disrupted in cross-section, increase in tenocytes with myofibroblastic differentiation (tendon repair cells), proteoglycan ground substance, and neovascularization. Classic inflammatory cells are usually absent.30 Although this aspect of tendinosis was first described 25 years ago31 and content experts have advocated a change in nomenclature (from “tendonitis” to tendinosis),27 use of the term “tendonitis” continues.32 Prolotherapy has been assessed as a treatment for four tendon disorders: lateral epicondylosis, hip adductor, Achilles tendinopathies, and plantar fasciitis (see Tables 15-1 and 15-3).

Lateral epicondylosis (LE, “tennis elbow”) is an important common condition of the upper extremity with an incidence of 4 to 7 per 1000 patients per year in primary care settings.33–35 Its greatest impact is on workers with repetitive and high-load upper extremity tasks and on athletes. Its most common cause may be low-load, high-repetition activities such as keyboarding, although formal data are lacking.36 Cost and time away from job or activity are significant.37,38 While many nonsurgical therapies have been tested for LE refractory to conservative measures, none have proved uniformly effective in the long term.39–41 Scarpone and colleagues conducted an RCT to determine whether prolotherapy improves self-reported elbow pain, and objectively measured grip strength and extension strength in patients with chronic LE (see Table 15-3). Twenty adults with at least 6 months of moderate-to-severe painful LE refractory to rest, NSAIDs, and corticosteroid injections, were randomized to prolotherapy with dextrose and morrhuate sodium (1 part 5% sodium morrhuate, 1.5 parts 50% dextrose, 0.5 parts 4% lidocaine, 0.5 parts 0.5% bupivacaine, and 3.5 parts normal saline) or control injections with normal saline. Three prolotherapy sessions were administered, with injection at the supracondylar ridge, lateral epicondyle, and annular ligament. Compared to controls, prolotherapy subjects reported significantly decreased pain scores at 8 and 16 weeks. These between-group differences in pain scores were associated with a significant improvement in prolotherapy subjects (from 5.1 ± 0.8 points at baseline, down to 0.5 ± 0.4 points at 16 weeks), whereas the controls did not report significant change (4.5 ± 1.7 points to 3.5 ± 1.5 points). In addition to pain reduction, prolotherapy subjects also showed significantly improved isometric strength compared to controls and improved grip strength compared to baseline. These clinical improvements seen in prolotherapy subjects were maintained at 52 weeks.

Two other recent evaluations of prolotherapy for LE have been performed. In a small RCT, Glick and coworkers reported 66% improvement on a disease specific questionnaire compared to 11.5% for controls (P =.09) receiving sham injections (see Table 15-3). This unpublished study formed the pilot data for a National Institutes of Health study now under way. (Prolotherapy for the treatment of chronic lateral epicondylitis; 1R21AT003969-01A1). In a prospective case series, Lyftogt42 reported 94% improvement compared to baseline scores using a novel subcutaneous injection technique (P < .05) (see Table 15-1).

Achilles tendinopathy is a common overuse injury seen in athletes and in the general population. This painful condition is a cause of considerable distress and disability.43

The strongest data supporting the use of prolotherapy for Achilles tendinopathy suggest that a combination of prolotherapy and eccentric exercise may be optimal treatment for this challenging condition. Yelland and colleagues13 compared the clinical and cost-effectiveness of eccentric loading exercises with prolotherapy injections (see Table 15-3). Forty subjects with painful mid-portion Achilles tendinosis completed a 12-week program of eccentric exercise (n = 15), or prolotherapy injections of hypertonic dextrose with lidocaine (n = 14) or combined treatment (n = 14). On a validated multidimensional survey, mean (95% CI) improvement in overall severity scores at 12 months were 23.7 (15.6 to 31.9) for eccentric exercise, 27.5 (12.8 to 42.2) for prolotherapy and 41.1 (29.3 to 52.9) for combined treatment. At 6 weeks and 12 months, these increases were significantly less for eccentric exercise than for combined treatment. Combined treatment also had the lowest incremental cost per additional responder compared with eccentric exercise alone.

Maxwell and coworkers conducted a well-designed case series to assess whether prolotherapy, administered during a mean of four injection sessions at 6-week intervals would decrease pain in 36 adults with painful Achilles tendinopathy (see Table 15-1). In this study, 25% dextrose solution was injected into hypoechoic regions of the Achilles tendon under ultrasound guidance. In addition to self-reported measures, the authors also assessed ultrasound-based tendon thickness, and the degree of hypoechogenicity and neovascularity—ultrasound findings recently reported to correlate to tendinopathy severity.44,45 At 52 weeks, prolotherapy-treated subjects reported decrease in VAS-assessed pain severity by 88%, 84%, and 78% during rest, “usual” activity, and sport, respectively. In addition, tendon thickness decreased significantly. The overall grade of tendon pathology, hypoechoic and anechoic tendon regions, and neovascularity were all improved in some, but not all, subjects who reported clinical improvement. Therefore, the relationship between ultrasound-assessed characteristics and the degree of clinical improvement remains unclear.

Hip adductor tendinopathy, associated with groin pain, is a common problem among those who engage in kicking sports.46 Topol and associates conducted a case series assessing prolotherapy for chronic groin pain, a condition involving pain and tenderness at tendon and ligament insertions at the groin area (see Table 15-1).47 Male athletes (N = 24), with an average duration of 15.5 months of groin pain in spite of standard therapy, were injected with 12.5% dextrose at the thigh and suprapubic abdominal insertions of the adductor tendon and at the symphysis pubis at 4-week intervals until pain resolved or subjects had no improvement for two consecutive sessions. On average, subjects received three prolotherapy sessions. At a mean of 17 months, subjects reported dramatic significant improvements on two pain scales (VAS and the Nirschl Pain Phase Scale). Of 24 subjects, 20 had no pain and 22 returned to sports without restrictions after therapy.

Plantar fasciitis is a common injury among athletes engaged in sports requiring running and among general primary care patients. It is reported to account for 15% of all adult foot complaints requiring professional consultation, and, in a 2002 survey of running-related injuries, plantar fasciitis was the third most prevalent injury.48,49 Among “standard of care” approaches, there is limited evidence for the effectiveness of any one treatment for plantar fasciitis, including steroid injections.50 Ryan and coworkers assessed prolotherapy for chronic plantar fasciitis refractory to conservative care.12 Twenty adults with an average of 21 months duration of heel pain underwent ultrasound-guided 25% dextrose injections for an average of three treatment sessions delivered at 6-week intervals (see Table 15-1). Pain scores were assessed, using a 100-point VAS, at baseline and at 11.8 months. Pain severity significantly improved at rest, during activities of daily living, and sport activities by 26.5, 49.7, and 56.5 points, respectively, compared to baseline, and 16 of 20 subjects reported good or excellent treatment effects.

Low Back Pain

Low back pain (LBP) is among the most common reasons patients see a primary care provider. Approximately 80% of Americans experience LBP during their lifetime. An estimated 15% to 20% of patients develop protracted pain, and approximately 2% to 8% experience chronic pain. LBP is second only to the common cold as a cause of lost work time. Productivity losses from chronic LBP approach $28 billion annually in the United States.51 Low back pain was the first condition to be evaluated using prolotherapy in an RCT context. Early studies reporting positive results suffered from confusing methodology or unclear reporting styles; the strongest study reported trends favoring prolotherapy compared to control groups without significant differences. More recent prospective case series reporting positive results compared to baseline conditions have attempted to refine inclusion criteria to better determine which, if any, patients benefit from prolotherapy (Tables 15-1, 15-2, and 15-3).

Nonspecific LBP. Four RCTs evaluated prolotherapy for musculoskeletal LBP; three used P2G as the injectant52–54 and the fourth used dextrose.55 Each study used a protocol involving injections to the ligamentous insertions of the L4-S1 spinous processes, sacrum, and ilium. Although outcome measures varied, a common measure was the percentage of participants reporting greater than 50% improvement in pain/disability scores at 6 months.

Two of these four RCTs reported positive findings compared to control injections. Ongley and coworkers52 and Klein and associates53 compared the treatment effects of prolotherapy combined with an adjacent treatment with injected steroids, spinal manipulation, and exercise. In the Ongley study,52 the intervention and control groups differed markedly on the make-up of initial injections and type of spinal manipulation associated with the injections. Significantly more subjects in the prolotherapy (88%) group reported at least 50% reduction in pain severity compared to controls (39%). Also, prolotherapy subjects, compared to controls, reported significantly decreased pain and disability levels.52 Klein and associates,53 used more similar treatment protocols in the two assessed groups, with subjects in both groups receiving steroid injections and spinal manipulation prior to prolotherapy. Again, significantly more prolotherapy subjects improved by 50% or more on pain or disability scores (77%) than did controls (53%). Pain grid scores were also significantly lower in the prolotherapy group, with individual pain (P = .06) and disability (P = .07) scores trending toward significance, compared to the control group.

Two of the four RCTs reported negative outcomes compared to control injections.54,55 Dechow and colleagues54 implemented a refined study protocol; subjects in both groups underwent three injection therapy sessions without adjacent spinal manipulation or physical therapy. Although both groups showed a trend toward improved severity scores on pain questionnaire, pain grid, and somatic perception measures, these changes did not reach statistical significance over time within or between groups. At 6 months, improvements in both groups were less than those of the other RCTs. The largest and most methodologically rigorous prolotherapy study published to date has been conducted by Yelland and colleagues.55 Study subjects (N = 110), with an average of 14 years of LBP, were randomized to one of four intervention groups: dextrose and physical therapy, dextrose and “normal activity”, saline injections (“control” injection) and physical therapy, or saline injections and “normal activity”. By 12 months, subjects in all groups reported improvement in pain level (26% to 44%) and disability (30% to 44%) scores, without significant differences between groups. The majority of subjects (55%) stated that their improvement in regard to pain and disability had been worth the effort of undergoing the intervention. The percentage of subjects who reached at least 50% pain reduction varied between 36% and 46%, although these differences were not statistically significant.

Overall, interpretation of findings from these four RCTs is challenging. Both experimental and control groups received different treatment protocols, and none of the trials was designed to elicit a possible mechanism of prolotherapy action. Therefore, it is impossible to attribute effects to prolotherapy or any other specific intervention. A recent Cochrane Collaboration systematic review56 did not find sufficient evidence to recommend prolotherapy for nonspecific LBP. However, these four RCTs present overall promising results, calling for well-designed, sufficiently-powered research. All RCTs report improvements for pain and disability in all treatment groups consisting of subjects with chronic, moderate-to-severe LBP. In particular, Yelland and colleagues55 reported clinical improvement in excess of minimal clinical important difference,57–59 and in excess of subjects’ own perception of the minimum improvement necessary for prolotherapy to be worthwhile (25% for pain and 35% for disability).24,55

Specific Causes of Low Back Pain

Prolotherapy research methods for LBP have progressed amid much debate surrounding effectiveness, indications, treatment protocols, and solution types.60,61 Given the promising aspects of the above RCTs for nonspecific LBP, combined with anecdotal clinical success, recent clinical researchers have begun to assess prolotherapy in patients with more specific forms of LBP and loss of function in an effort to determine which specific causes of LBP are most responsive to prolotherapy.

Cusi and colleagues assessed 25 subjects with sacroiliac joint dysfunction and pain, refractory to 6 months or more of physical therapy, and with documented failure of load transfer (disability) at the sacroiliac joint.62 They used a relatively strong prolotherapy solution of 18% dextrose, delivered in three sets of injections over 12 weeks. Compared to baseline, pain and disability scores on three multidimensional outcome measures significantly improved at 26 month follow-up in excess of minimal clinically important difference.

Khan and colleagues assessed 37 subjects with refractory coccygodynia.63 Using 25% dextrose in up to three prolotherapy injection sessions over 2 months, average pain scores (evaluated using a 0 to 10 visual analog scale [VAS]), significantly decreased from a baseline score of 8.5 to 2.5 points at 2 months, far in excess of reported minimal clinical important difference for chronic pain.64 The authors reported “good” pain relief for 30 of 37 subjects, and “no improvement” for those remaining.7

In an especially novel study, Miller and colleagues assessed prolotherapy for leg pain due to moderate-to-severe degenerative disc disease as determined by computed tomography.65 Subjects (N = 76) who failed physical therapy and had substantial but temporary pain relief with two fluoroscopically-guided epidural steroid injections were included. After an average of 3.5 sessions of biweekly, fluoroscopically-guided injections to the relevant disc space with 25% dextrose with bupivacaine, 43% of responders showed a significant, sustained treatment response of 71% improvement in pain score, with VAS score for responders at 8.9 (±1.4), 2.5 (±2.0), and 2.6 (±2.2) at baseline, 2 and 18 months, respectively. Although these three recent studies of prolotherapy for “specific” LBP were uncontrolled, they suggest the need for future RCTs with more focused clinical indications of axial pain and disability.

Osteoarthritis

Prolotherapy has been assessed as a treatment for knee and finger osteoarthritis20,66 and is the subject of ongoing studies.67 Arthritis is a leading cause of disability in the world and in the United States where it affects 43 million people.68–70 Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis and the most common joint disorder.71 In the United States, symptomatic knee OA is present in up to 6% of the population older than 30 years,71 and has an overall incidence of 360,000 cases per year.72 Incidence increases up to 10-fold from ages 30 to 65 and more thereafter.73 OA results in a high burden of disease and substantial economic impact through its high prevalence, time lost off work, and frequent use of health care resources.68,74

Allopathic and CAM treatment recommendations for OA, aimed at correcting modifiable risk factors, symptom control, and disease modification, have been published.75,76 Although these modalities may help some patients, none provides definitive pain control or disease modification for patients with knee OA. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has recently evaluated the most common standard treatment options including glucosamine, chondroitin, viscosupplementation, and arthroscopic débridement.77 These have not proven to be superior to placebo. The high burden of knee OA and the absence of cure continue to stimulate intense search for new agents to modify disease and control symptoms.

Reeves and colleagues assessed prolotherapy as a treatment for knee and finger OA.20,66 Subjects with finger or knee pain and radiologic evidence of OA were randomly assigned to receive three injection sessions of either prolotherapy with 10% dextrose and lidocaine, or lidocaine and bacteriostatic water (control group). In the knee OA trial, subjects in both groups reported significant improvements in pain and swelling scores, number of buckling episodes, and flexion range of motion compared to baseline, but without statistically significant differences between the groups. Surprising and potentially important 12-month follow-up in both studies included improved radiologic features of OA on plain x-ray films: authors reported decreased joint space narrowing and osteophyte grade in the finger study, and increased patellofemoral cartilage thickness in the knee study. These radiologic findings suggest disease modification properties of prolotherapy. However, whether or not subjects in the knee study had a baseline concomitant meniscal pathology was not reported or included in entry criteria. Furthermore, the ability of plain radiographs to quantify patellofemoral cartilage thickness is questionable, thereby limiting the impact of these findings. In the finger OA trial, intervention subjects significantly improved in “pain with movement” and “flexion range” scores compared to controls; pain scores at rest and with grip showed a tendency to improvement without reaching statistical significance.

A more rigorous set of knee OA assessments is currently under way. Rabago and colleagues are conducting an NIH-NCCAM sponsored RCT assessing prolotherapy for knee OA using a more complex “whole organ” clinical and assessment approach (“The efficacy of prolotherapy for osteoarthritic knee pain;” NIH-NCCAM 5K23AT001879-05). Although degeneration of articular cartilage is a hallmark of knee OA, the pathology of other structures in and around the knee joint may also contribute to the pain and disability of knee OA, including osteophytes, subchondral cysts, joint effusions, ligament and tendon tears, Baker cysts, synovitis, meniscal tears, and subchondral bone marrow edema within the knee joint.78–83 Therefore, the injection protocol includes a comprehensive set of extra- and intra-articular injections (Figs. 15-1 and 15-2). The results of prolotherapy injections will be compared to those of subjects in two other groups receiving control saline injections and at-home physical therapy injections, respectively. The primary outcome will be the Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC)84 questionnaire. Magnetic resonance imaging has been identified as an appropriate imaging modality with which to evaluate disease-modifying OA therapies in clinical trials.79,85,86 This study will assess the changes in response to prolotherapy using validated clinical assessment and magnetic resonance imaging in a subset of subjects.

Side Effects, Adverse Events, and Contraindications

Common Side Effects

The main risk of prolotherapy is pain and mild bleeding as a result of needle trauma. Patients frequently report pain, a sense of fullness, and occasional numbness at the injection site at the time of injections. These side effects are typically self-limited. A post-injection pain flare during the first 72 hours after the injections is common clinically but its incidence has not been well documented. An ongoing study of prolotherapy for knee OA pain has noted that 10% to 20% of subjects experience such flares.122 Pain flares are likewise typically self-limited and usually respond well to acetaminophen (500 to 650 mg every 4 hours as needed). On rare occasions, the occurrence of strong, post-injection pain may require treatment with narcotic medication. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents are not routinely used after the procedure but may be indicated if the pain does not resolve with other measures. Most patients with pain flares experience diminution of pain in 5 to 7 days after injections; regular activities can be progressively resumed at this time.

Adverse Events

While prolotherapy performed by an experienced injector appears to be safe, the injection of ligaments, tendons, and joints with irritant solutions raises safety concerns. Theoretic risks of prolotherapy injections include lightheadedness, allergic reaction, infection, or neurological (nerve) damage. Injections should be performed using universal precautions and the patient should be prone if possible. Dextrose is extremely safe; it is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for intravenous treatment of hypoglycemia and for caloric supplementation.123 As of 1998, FDA records for intravenous 25% dextrose solution reported no adverse events to Abbott Laboratories in 60 years.124 Morrhuate sodium is a vascular sclerosant used in gastrointestinal procedures and vein sclerosing. Allergic reactions to morrhuate sodium are rare. Although P2G is not FDA approved for any indication, it has not been reported in clinical trials to cause significant side effects or adverse events.

Historically, a small number of significant, prolotherapy-related complications have been reported. They were associated with perispinal injections for back or neck pain, using highly concentrated solutions, and included five cases of neurologic impairment from spinal cord irritation125–127 and one death in 1959 following prolotherapy with zinc sulfate for low back pain.125 Neither zinc sulfate nor concentrated prolotherapy solutions are currently in general use. In a survey of 95 clinicians using prolotherapy, there were 29 reports of pneumothoraces after prolotherapy for back and neck pain, 2 of which required hospitalization for a chest tube, and 14 cases of allergic reactions, although none were classified as serious.5 A more recent survey of practicing prolotherapists yielded similar results for spinal prolotherapy: spinal headache, pneumothoraces, nerve damage and nonsevere spinal cord insult, and disc injury were reported.128 The authors concluded these events were no more common in prolotherapy than for other spinal injection procedures. No serious side effects or adverse events were reported for prolotherapy when used for peripheral joint indications.

Prolotherapy in Practice

Similar to corticosteroid injections, prolotherapy is an unregulated procedure without certification by any governing body. Formal training is not provided by most medical schools, residencies, and fellowships. However, prolotherapy, to be performed appropriately and safely, requires specialized training. In the United States, it is taught to physicians and other health care providers (authorized to deliver joint-type injections) in semiformal workshops and formal continuing medical education (CME) by several organizations, including university settings (Table 15-5).

Table 15-5 Educational and Informational Prolotherapy Resources

| Name/URL | Comments |

|---|---|

| Continuing medical education (CME) on the basics of prolotherapy. This 3.5 day conference is offered through the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. All aspects of clinical and research aspects of prolotherapy are covered. | |

| The Hackett Hemwall Foundation is a nonprofit medical foundation whose mission is to provide high-quality treatment of musculoskeletal problems to underserved people around the world. Physicians listed on the site have completed the Foundation’s high-volume continuing medical education experience in prolotherapy. | |

| This site lists physicians by state who perform prolotherapy. It includes contact information and a short biography and prolotherapy credentials. Physicians pay to list themselves on this site. | |

| The American Association of Orthopaedic Medicine is a nonprofit organization that provides information and educational programs on comprehensive nonsurgical musculoskeletal treatment including prolotherapy. This searchable site lists AAOM members who perform prolotherapy. |

Patients and physicians who desire consultation for prolotherapy may have difficulty finding an appropriate consulting prolotherapist. Online resources (see Table 15-5) are available that can help locate a prolotherapist, although information is limited by lack of a credentialing structure and governing body for prolotherapy.

Despite limited institutional support, interest in prolotherapy is increasing, and it is performed in increasing numbers, primarily in two settings. For several decades, prolotherapy has been mostly performed outside of mainstream medicine by independent physicians. More recently, multispecialty groups that include family or sports medicine physicians, physiatrists, orthopedic surgeons, neurologists, or anesthesiologists have been incorporating prolotherapy as a result of positive clinical experience and research reports. Prolotherapy is one of several injection therapies that may promote healing of chronically injured soft tissue. Other therapies receiving active clinical and research attention for chronic musculoskeletal pain include whole blood, platelet-rich plasma and polidocanol injections.11 In both settings, prolotherapy is viewed as a valued procedure, primarily reserved for patients who have failed other treatments or in patients who are not surgical candidates.

The Authors’ Clinic

Clinical Recommendations

Present data suggest that prolotherapy is likely an effective therapy for painful overuse tendinopathy. Specifically, Scarpone and colleagues10 provide level A evidence for prolotherapy as an effective therapy for lateral epicondylosis. Subjects with refractory lateral epicondylosis and treated with prolotherapy reported significant reduction in pain and improved isometric strength compared to those who received control injections. These findings are supported by the Yelland,13 Maxwell,7 Topol,47 and Ryan12 studies that report strong case series results for Achilles, hip adductor, and plantar fasciitis, respectively, and provide level B evidence for these conditions. Given that the underlying mechanism of injury and pathophysiologic effects are likely similar for tendinopathies, prolotherapy is a reasonable option for other overuse tendinopathies as well. Randomized controlled trials for all three tendinopathies and for other tendinopathies are indicated.

Recommendations are more difficult to make for osteoarthritis and low back pain, both of which are associated with more complex anatomy and less clear pathophysiology than that seen in tendinopathies. Side effect and potential adverse events of prolotherapy are likely to be more serious when performed for spinal or intra-articular indications and must be weighed against the potential for improvement. Existing studies provide level B evidence that prolotherapy is effective for nonspecific low back pain compared to a patient’s baseline condition. Given that subjects with refractory, disabling low back pain significantly improved compared to their own baseline status in the Yelland study,55 patients may reasonably try prolotherapy when performed by an experienced injector. Future studies with more focused inclusion criteria may help determine which specific low back pathologies respond to prolotherapy. Existing studies provide level B evidence that prolotherapy is effective for knee and finger osteoarthritis compared to control injections.20,66 Prolotherapy by an experienced physician is a treatment modality worthy of consideration by primary care physicians for these conditions, especially when patients are refractory to more conventional therapy.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of Jessica Grettie, BS, for her ongoing efforts in prolotherapy research.

1. Hackett G.S., Hemwall G.A., Montgomery G.A. Ligament and tendon relaxation treated by prolotherapy, 5th ed. Oak Park, Ill: Hemwall; 1993. Gustav A

2. Linetsky F.S., Frafael M., Saberski L. Pain management with regenerative injection therapy (RIT). In: Weiner R.S., editor. Pain Management. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 2002:381-402.

3. Matthews J.H. Nonsurgical treatment of pain in lumbar spinal stenosis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59(2):280-284.

4. Schnirring L. Are your patients asking about prolotherapy? Physician Sportsmed. 2000;28(8):15-17.

5. Dorman T.A. Prolotherapy: A survey. J Orthop Med. 1993;15(2):49-50.

6. Linetsky F.S., Botwin K., Gorfine L., Jay G.W. Regenerative injection therapy (RIT): Effectiveness and appropriate usage. Florida Acad Pain Med. 2001. http://fapmmed.net/Position.htm.

7. Maxwell N.J., Ryan M.B., Taunton J.E., et al. Sonographically guided intratendinous injection of hyperosmolar dextrose to treat chronic tendinosis of the Achilles tendon: A pilot study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(4):W215-220.

8. Jensen K.T., Rabago D.P., Best T.M., et al. Early inflammatory response of knee ligaments to prolotherapy in a rat model. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:816-823.

9. Jensen K.T., Rabago D.P., Best T.M., et al. Response of knee ligaments to prolotherapy in a rat injury model. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:1347-1357.

10. Scarpone M., Rabago D., Zgierska A., et al. The efficacy of prolotherapy for lateral epicondylosis: A pilot study. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18:248-254.

11. Rabago D., Best T.M., Zgierska A., et al. A systematic review of four injection therapies for lateral epicondylosis: Prolotherapy, polidocanol, whole blood and platelet rich plasma. Br J Sports Med.. 2009. 43:471-481

12. Ryan M.B., Wong A.D., Gillies J.H., et al. Sonographically guided intratendinous injections of hyperosmolar dextrose/lidocaine: A pilot study for the treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:303-306.

13. Yelland M.J., Sweeting K.R., Lyftogt J.A., et al. Prolotherapy injections and eccentric loading exercises for painful Achilles tendinosis: A randomised trial. Br J Sports Med. 2010. Jul 6 [Epub ahead of print]

14. Liu Y.K., Tipton C.M., Matthes R.D., et al. An in-situ study of the influence of a sclerosing solution in rabbit medial collateral ligaments and its junction strength. Connect Tissue Res. 1983;11:95-102.

15. Maynard J.A., Pedrini V.A., Pedrini-Mille A., et al. Morphological and biochemical effects of sodium morrhuate on tendons. J Orthop Res. 1985;3:236-248.

16. Banks A. A rationale for prolotherapy. J Orthop Med. 1991;13(3):54-59.

17. Hoksrud A., Ohberg L., Alfredson H., Bahr R. Ultrasound-guided sclerosis of neovessels in painful chronic patellar tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1738-1746.

18. Zeisig E., Fahlström M., Ohberg L., Alfredson H. A 2-year sonographic follow-up after intratendinous injection therapy in patients with tennis elbow. Br J Sports Med. 2010. 44:584-587

19. Kim S.R., Stitik T.P., Foye P.M. Critical review of prolotherapy for osteoarthritis, low back pain, and other musculoskeletal conditions: A physiatric perspective. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;83(5):379-389.

20. Reeves K.D., Hassanein K. Randomized prospective double-blind placebo-controlled study of dextrose prolotherapy for knee osteoarthritis with or without ACL laxity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2000;6(2):68-80.

21. Aneja A., Karas S.G., Weinhold P.S. Suture plication, thermal shrinkage and sclerosing agents: effects on rat patellar tendon length and biomechanical strength. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1729-1734.

22. Jensen K.T. PhD Dissertation: Healing response of knee ligaments to prolotherapy in a rat model. Madison, Wisc: Biomedical Engineering, University of Wisconsin; 2006.

23. Rabago D., Best T.M., Beamsley M., Patterson J. A systematic review of prolotherapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clin J Sports Med. 2005;15(5):376-380.

24. Yelland M., Yeo M., Schluter P. Prolotherapy injections for chronic low back pain: Results of a pilot comparative study. Aust Musculoskel Med. 2000;5(2):20-23.

25. Ernst E., Pittler M.H., Stevinson C., White A. Randomised clinical trials: Pragmatic or fastidious? Focus Altern Complementary Ther. 2001;6:179-180.

26. Verhagen A.P., de Vet H.C., de Bie R.A., et al. The Delphi list: A criteria list for quality assessment of randomized trials conducting reviews developed Delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(12):1235-1241.

27. Khan K.M., Cook J.L., Kannus P., et al. Time to abandon the ‘tendinitis’ myth. BMJ. 2002;324:626-627.

28. Bongers P.M. The cost of shoulder pain at work. Variation in work tasks and good job opportunities are essential for prevention. BMJ. 2001;322:64-65.

29. Wilson J.J., Best T.M. Common overuse tendon problems: A review and recommendations for treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:811-818.

30. Khan K.M., Cook J.L., Bonar F., et al. Histopathology of common tendinopathies. Update and implications for clinical management. Sports Med. 1999;27:393-408.

31. Puddu G., Ippolito E., Postacchini F. A classification of Achilles tendon disease. Am J Sports Med. 1976;4:145-150.

32. Johnson G.W., Cadwallader K., Scheffel S.B., Epperly T.D. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:843-848.

33. Verhaar J.A. Tennis elbow: Anatomical, epidemiological and therapeutic aspects. Int Orthop. 1994;18:263-267.

34. Hamilton P.G. The prevalence of humeral epicondylitis: A survey in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1986;36:464-465.

35. Kivi P. The etiology and conservative treatment of humeral epicondylitis. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1983;15:37-41.

36. Gabel G.T. Acute and chronic tendinopathies at the elbow. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:138-143.

37. Ono Y., Nakamura R., Shimaoka M., et al. Epicondylitis among cooks in nursery schools. Occup Environ Med. 1998;55:172-179.

38. Ritz B.R. Humeral epicondylitis among gas and waterworks employees. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1995;21:478-486.

39. Buchbinder R., Green S., White M., et al. Shock wave therapy for lateral elbow pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002:1. CD003524

40. Smidt N., van der Windt D.A., Assendelft W.J., et al. Corticosteroid injections, physiotherapy, or a wait-and-see policy for lateral epicondylitis: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:657-662.

41. Struijs P.A., Smidt N., Arola H., et al. Orthotic devices for the treatment of tennis elbow. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002:1. CD001821

42. Lyftogt J. Subcutaneous prolotherapy treatment of refractory knee, shoulder and lateral elbow pain. Aust Musculoskel Med. 2007;12:110-112.

43. Kvist M. Achilles tendon injuries in athletes. Sports Med. 1994;18:173-201.

44. Zeisig E., Ohberg L., Alfredson H. Extensor origin vascularity related to pain in patients with tennis elbow. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:659-663.

45. Alfredson H., Ohberg L. Sclerosing injections to areas of neovascularization reduce pain in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: A double-blind randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13:338-344.

46. Holmich P., Uhrskou P., Ulnits L. Effectiveness of active physical training as treatment of long-standing adductor-related groin pain in athletes: A randomized trial. Lancet. 1999;353:439-443.

47. Topol G.A., Reeves K.D., Hassanein K.M. Efficacy of dextrose prolotherapy in elite male kicking-sport athletes with chronic groin pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:697-702.

48. Buchbinder R. Clinical practice. Plantar fasciitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2159-2166.

49. Taunton J.E., Ryan M.B., Clement D.B., et al. A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:95-101.

50. Crawford F., Thomson C. Interventions for treating plantar heel pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:3. CD000416

51. Wheeler AH: Low Back Pain and Sciatica. http://www.emedicine.com/neuro/topic516.htm. 2010.

52. Ongley M.J., Klein R.G., Dorman T.A., et al. A new approach to the treatment of chronic low back pain. Lancet. 1987;2:143-146.

53. Klein R.G., Eek B.C., DeLong W.B., Mooney V. A randomized double-blind trial of dextrose-glycerine-phenol injections for chronic, low back pain. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6(1):23-33.

54. Dechow E., Davies R.K., Carr A.J., Thompson P.W. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of sclerosing injections in patients with chronic low back pain. Rheumatology. 1999;38:1255-1259.

55. Yelland M.J., Glasziou P.P., Bogduk N., et al. Prolotherapy injections, saline injections, and exercises for chronic low back pain: A randomized trial. Spine. 2004;29(1):9-16.

56. Yelland M.J., Del Mar C., Pirozzo S., Schoene M.L. Prolotherapy injections for chronic low back pain: A systematic review. Spine. 2004;29:2126-2133.

57. Bellamy N., Carr A., Dougados M., et al. Towards a definition of “difference” in osteoarthritis. J Rheumatology. 2001;28(2):427-430.

58. Redelmeier D.A., Guyatt G.H., Goldstein R.S. Assessing the minimal important difference in symptoms: A comparison of two techniques. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1215-1219.

59. Wells G.A., Tugwell P., Kraag G.R., et al. Minimum important difference between patients with rheumatoid arthritis: The patient’s perspective. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:557-560.

60. Loeser J.D. Point of view. Spine. 2004;29(1):16.

61. Reeves K.D., Klein R.G., DeLong W.B. Letter to the editor. Spine. 2004;29(16):1839-1840.

62. Cusi M., Saunders J., Hungerford B., et al. The use of prolotherapy in the sacroiliac joint. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:100-104.

63. Khan S.A., Kumar A., Varshney M.K., et al. Dextrose prolotherapy for recalcitrant coccygodynia. J Orthop Surg. 2008;16:27-29.

64. Farrar J.T., Young J.P., LaMoreaux L., et al. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical rating scale. Pain. 2001;94:149-158.

65. Miller M.R., Mathews R.S., Reeves K.D. Treatment of painful advanced internal lumbar disc derangement with intradiscal injection of hypertonic dextrose. Pain Physician. 2006;9:115-121.

66. Reeves K.D., Hassanein K. Randomized, prospective, placebo-controlled double-blind study of dextrose prolotherapy for osteoarthritic thumb and finger (DIP, PIP, and trapeziometacarpal) joints: Evidence of clinical efficacy. J Altern Complement Med. 2000;6(4):311-320.

67. Rabago D: The efficacy of prolotherapy in osteoarthritic knee pain. NIH-NCCAM Grant, 1K23 AT001879–01; 2004-2009; manuscripts in progress.

68. Reginster J.Y. The prevalence and burden of arthritis. Rheumatology. 2002;41(suppl 1):3-6.

69. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Prevalence and impact of chronic joint symptoms-seven states, 1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47:345-351.

70. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of disabilities and associated health conditions—United States, 1991-1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43:730-739.

71. Felson D.T., Zhang Y. An update on the epidemiology of knee and hip osteoarthritis with a view to prevention. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(8):1343-1355.

72. Wilson M.G., Michet C.J., Ilstrup D.M., Melton L.J. Ideopathic symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: A population-based incidence study. Mayo Clic Proc. 1990;65:1214-1221.

73. Oliveria S.A., Felson D.T., Klein R.A., et al. Estrogen replacement therapy and the development of osteoarthritis. Epidemiology. 1996;7:415-419.

74. Levy E., Ferme A., Perocheau D., et al. Socioeconomic costs of osteoarthritis in France. [Article in French]. Rev Rhum Ed Fr. 1993;60:63S-67S.

75. Felson D.T., Lawrence R.C., Hochberg M.C., et al. Osteoarthritis: new insights, part 2: treatment approaches. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:726-737.

76. Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1905-1915.

77. Samson D.J., Grant M.D., Ratko T.A., et al. Treatment of primary and secondary osteoarthritis of the knee. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2007;157:1-157.

78. Hill C.L., Gale D.G., Chaisson C.E., et al. Knee effusions, popliteal cysts, and synovial thickening: Association with knee pain in osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol, 28. 2001:1330-1337.

79. Guermazi A., Zaim S., Taouli B., et al. MR findings in knee osteoarthritis. Eur Radiol, 13. 2003;:1370-1386.

80. Hayes C.W., Jamadar D.A., Welch G.W., et al. Osteoarthritis of the knee: Comparison of MR imaging findings with radiographic severity measurements and pain in middle-aged women. Radiology. 2005;237:998-1007.

81. Sowers M.F., Hayes C., Jamadar D., et al. Magnetic resonance-detected subchondral bone marrow and cartilage defect characteristics associated with pain and x-ray-defined knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 11. 2003;:387-393.

82. Link T.M., Steinbach L.S., Ghosh S., et al. Osteoarthritis: MR imaging findings in different stages of disease and correlation with clinical findings. Radiology, 226. 2003:373-381.

83. Wluka A.E., Ding C., Jones G., Cicuttini F.M. The clinical correlates of articular cartilage defects in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: A prospective study. Rheumatology, 44. 2005:1311-1316.

84. Bellamy N., Buchanan W.W., Goldsmith C.H., et al. Validation study of WOMAC: A health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes in antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833-1840.

85. Peterfy C., Woodworth T., Altman R. Workshop for consensus on osteoarthritis imaging: MRI of the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:44-45.

86. Peterfy C.G., Gold G., Eckstein F., et al. MRI protocols for whole-organ assessment of the knee in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 14. 2006:A95-A111.

87. Gedney E. Special technic hypermobile joint: a preliminary report. Osteopath Prof. 1937;4(9):30-31.

88. Shuman D. Luxation recurring in the shoulder. Osteopath Prof. 1941;8(6):11-14.

89. Bahme B.B. Observations on the treatment of hypermotile joints by injection. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1945;45(3):101-109.

90. Gedney E.H. Disk syndrome: New approach in the treatment of symptomatic intervertebral disk. Osteopath Prof. 1951;18(12):11-14.

91. Gedney E.H. Technique for sclerotherapy in the management of hypermobile sacroiliac. Osteopath Prof. 1952;19:37-38.

92. Hackett G.S. Joint stabilization through induced ligament sclerosis. Ohio Med. 1953;49(10):877-884.

93. Shuman D. Sclerotherapy: Statisitics on its effectiveness of unstable joint conditions. Osteopath Prof. 1954;21:11-15. 37–38

94. Hackett G.S. Shearing injury to the sacroiliac joint. J Int Coll Surg. 1954;22:631-642.

95. Neff F. Low back pain and disability. West Med. 1960;1:12-14. 27-33

96. Myers A. Prolotherapy treatment of low back pain and sciatica. Bull Hosp Joint Dis. 1961;22:48-55.

97. Hackett G.S., Huang T.C., Raftery A. Prolotherapy for headache. Pain in the head and neck, and neuritis. Headache. 1962;2:20-28.

98. Kayfetz D.O., Blumenthal L.S., Hackett G.S., et al. Whiplash injury and other ligamentous headache—its managment with prolotherapy. Headache. 1963;3:21-28.

99. Kayfetz D.O. Occipito-cerivical (whiplash) injuries treated by prolotherapy. Med Trial Tech Q. 1963;9:9-29.

100. Peterson T.H. Injection treatment for back pain. Am J Orthop. 1963;5:320-321.

101. Barbor R. A treatment for chronic low back pain. Paris: Paper presented at: Proceedings of IV Internationhal Congress of Physical Medicine; 1964. 6-11

102. Blumenthal L. Injury to the cervical spine as a cause of headache. Postgrad Med. 1974;56:147-153.

103. Leedy R., Kulik A.L. Analysis of 50 low back cases 6 years after treatment by joint ligament sclerotherapy (prolotherapy). Osteopathic Med. 1976;6:15-22.

104. Leedy R.F. Applications of sclerotherapy to specific problems. Osteopathic Med. 1977;2:79-97.

105. Leedy R. The challenge of a new skill. N Jersey Assoc Osteopat Phys Surg J. 1982;81(7):9-13.

106. Bourdeau Y. Five-year follow-up on sclerotherapy/prolotherapy for low back pain. Manual Med. 1988;3:155-157.

107. Ongley M.J., Dorman T.A., Eck B.C., et al. Ligament instability of knees: A new approach to treatment. Manual Med. 1988;3:152-154.

108. LaCourse M., Moore K., David K., et al. A report on the asymmetry of iliac inclincations. J Orthop Med. 1990;12(3):69-72.

109. Dorman T.A. Treatment for spinal pain arising in ligaments-using prolotherapy: A retrospective study. J Orthop Med. 1991;13(1):13-19.

110. Schwartz R.G., Sagedy N. Prolotherapy: A literature review and retrospective study. J Neurol Orth Med S. 1991;12:220-223.

111. Hirschberg G.G., Williams K.A., Byrd J.B. Diagnosis and treatment of ileocostal friction syndromes. West J Med. 1992;14(2):35-39.

112. Reeves K.D. Treatment of consecutive severe fibromyalgia patients with prolotherapy. J Orthopaedic Med. 1994;16(3):84-89.

113. Dorman T.A., Cohen R.E., Dasig D., et al. A. Energy efficiency during human walking before and after prolotherapy. J Orthop Med. 1995;17(1):24-26.

114. Matthews J.N., Altman D.G., Campbell M.J., Royston P. Analysis of serial measurements in medical research. BMJ. 1990;300:230-235.

115. Reeves K.D., Harris A.I. Recurrent dislocation of total knee prostheses in a large patient: Case report of dextrose proliferant use. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:1039.

116. Reeves K.D., Hassanein K.M. Long-term effects of dextrose prolotherapy for anterior cruciate ligament laxity. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(3):58-62.

117. Hooper R.A., Ding M. Retrospective case series on patients with chronic spinal pain treated with dextrose prolotherapy. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10:670-674.

118. Hooper R.A., Sherman S.T., Frizzell J.B. Case report of whiplash related chronic neck pain treated with intra-articular prolotherapy. J Whiplash Rel Disord. 2005;2:23-27.

119. Lazzara M.A. The non-surgical repair of a complete Achilles tendon rupture by prolotherapy: biological reconstruction. A case report. J Orthop Med. 2005;27:128-132.

120. Naeim F., Froetscher L., Hirschberg G.G. Treatment of the chronic iliolumbar syndrome by infiltration of the iliolumbar ligament. West J Med. 1982;136(4):372-374.

121. Glick R.M., Day R.D., Stone D.A., Cortazzo M. Prolotherapy for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: A double-blind pilot study. Edmonton, Canada: Paper presented at: North American Research Conference on Complementary and Integrative Medicine; 2006.

122. Rabago D., Zgierska A., Mundt M., et al. Efficacy of prolotherapy for knee osteoarthritis: Results of a prospective case series (poster presentation). North American Research Conference on Complementary and Integrative Medicine. 2009.

123. AbbottLabs: FDA indications for 50% dextrose. http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/nda/98/19445-s4-s6.htm; 2004.

124. AbbottLabs: Approval documentation for 25% dextrose submitted to FDA by Abbott Laboratories. [Online documentation].

125. Schneider R.C., Williams J.J., Liss L. Fatality after injection of sclerosing agent to precipitate fibro-osseous proliferation. J Am Med Assoc. 1959;170(15):1768-1772. 1959

126. Keplinger J.E., Bucy P.C. Paraplegia from treatment with sclerosing agents—report of a case. JAMA. 1960;173(12):1333-1336.

127. Hunt W.E., Baird W.C. Complications following injection of sclerosing agent to precipitate fibro-osseous proliferation. J Neurosurg. 1961;18:461-465.

128. Dagenais S., Ogunseitan O., Haldeman S., et al. Side effects and adverse events related to intraligamentous injection of sclerosing solutions (prolotherapy) for back and neck pain: A survey of practitioners. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:909-913.