Pneumonia

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The host defenses of the lung are constantly challenged by a variety of organisms, including both viruses and bacteria (see Chapter 22). Viruses in particular are likely to avoid or overwhelm some of the upper respiratory tract defenses, causing a transient, relatively mild clinical illness with symptoms limited to the upper respiratory tract. When host defense mechanisms of the upper and lower respiratory tracts are overwhelmed, microorganisms may establish residence, proliferate, and cause a frank infectious process within the pulmonary parenchyma. With particularly virulent organisms, no major impairment of host defense mechanisms is needed; pneumonia may occur even in normal and otherwise healthy individuals. At the other extreme, if host defense mechanisms are quite impaired, microorganisms that are not particularly virulent and unlikely to cause disease in a healthy host may produce a life-threatening pneumonia.

In practice, several factors frequently cause enough impairment of host defenses to contribute to the development of pneumonia, even though individuals with such impairment are not considered “immunosuppressed.” Viral upper respiratory tract infections, ethanol abuse, cigarette smoking, heart failure, and preexisting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are a few of the contributing factors. More severe impairment of host defenses is caused by diseases associated with immunosuppression (e.g., advanced AIDS), various underlying malignancies (particularly leukemia and lymphoma), and use of corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive or cytotoxic drugs. In these cases associated with impairment of host defenses, individuals are susceptible to both bacterial and more unusual nonbacterial infections (see Chapters 24 to 26).

Bacteria

S. pneumoniae, a normal inhabitant of the oropharynx in a large proportion of adults, is a gram-positive coccus seen in pairs or diplococci. Pneumococcal pneumonia is commonly acquired in the community (i.e., in nonhospitalized patients) and frequently occurs following a viral upper respiratory tract infection. The organism has a polysaccharide capsule that interferes with phagocytosis and therefore is an important factor in its virulence. There are many antigenic types of capsular polysaccharide, and for host defense cells to phagocytize the organism, antibody against the particular capsular type must be present. Antibodies contributing in this way to the phagocytic process are called opsonins (see Chapter 22).

Many other types of bacteria can cause pneumonia. Because all of them cannot be covered in this chapter, the interested reader should consult some of the more detailed publications listed in the references at the end of this chapter.

Pathology

Lobar Pneumonia.Lobar pneumonia has classically been described as a process not limited to segmental boundaries but rather tending to spread throughout an entire lobe of the lung. Spread of the infection is believed to occur from alveolus to alveolus and from acinus to acinus through interalveolar pores known as the pores of Kohn. The classic example of a lobar pneumonia is that due to S. pneumoniae, although many cases of pneumonia documented as being due to pneumococcus do not necessarily follow this typical pattern.

Bronchopneumonia.In bronchopneumonia, distal airway inflammation is prominent along with alveolar disease, and spread of the infection and the inflammatory process tends to occur through airways rather than through adjacent alveoli and acini. Whereas lobar pneumonias appear as dense consolidations involving part or all of a lobe, bronchopneumonias are more patchy in distribution, depending on where spread by airways has occurred. Many bacteria, such as staphylococci and a variety of gram-negative bacilli, may produce this patchy pattern.

Interstitial Pneumonia.In some cases of pneumonia, the organisms are not highly destructive to lung tissue even though an exuberant inflammatory process may be seen. Pneumococcal pneumonia classically (although not always) behaves in this way, and the healing process is associated with restoration of relatively normal parenchymal architecture. In other cases, when the organisms are more destructive, tissue necrosis may occur, with resulting cavity formation or scarring of the parenchyma. Many cases of staphylococcal and anaerobic pneumonias follow this more destructive course.

Diagnostic Approach

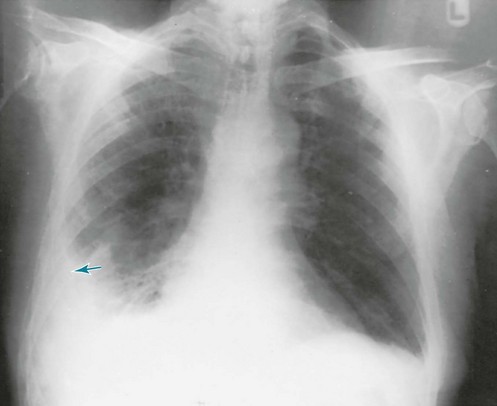

As with other disorders affecting the pulmonary parenchyma, the single most useful tool for assessing pneumonia at the macroscopic level is the chest radiograph. The radiograph not only confirms the presence of a pneumonia, it also shows the distribution and extent of disease and sometimes gives clues about the nature of the etiologic agent. The classic pattern for S. pneumoniae (pneumococcus) and K. pneumoniae is a lobar pneumonia (Fig. 23-1). Staphylococcal and many of the gram-negative pneumonias may be localized or extensive and often follow a patchy distribution (Fig. 23-2). Mycoplasma organisms can produce a variety of radiographic presentations, classically described as being more impressive than the clinical picture would suggest. Pneumonias caused by aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions characteristically involve the dependent regions of lung: the lower lobe in the upright patient or the posterior segment of the upper lobe or superior segment of the lower lobe in the supine patient (Fig. 23-3).

When sputum is not spontaneously expectorated by the patient, other methods for obtaining respiratory secretions (or even material directly from the lung parenchyma) may be necessary. Techniques that have been used—flexible bronchoscopy, needle aspiration of the lung, and occasionally surgical lung biopsy—are described in greater detail in Chapter 3. Techniques for testing urine for the presence of pneumococcal antigens are becoming increasingly useful.

Therapeutic Approach: General Principles and Antibiotic Susceptibility

No definitive forms of therapy are available for most viral pneumonias, although rapid advances in this field may lead to development of more clinically useful therapeutic agents. Influenza vaccine (see Chapter 22) is effective in preventing influenza in the majority of individuals who receive it, whereas antiviral agents (amantadine or rimantadine for influenza A, a neuraminidase inhibitor such as zanamivir or oseltamivir for influenza A or B) may reduce the duration or severity of the illness if given soon after onset of clinical symptoms.

Other modalities of therapy are mainly supportive. Chest physical therapy and other measures to assist clearance of respiratory secretions are useful for some patients with pneumonia, particularly if neuromuscular disease or other factors impair the effectiveness of the patient’s cough. If patients have inadequate gas exchange as demonstrated by significant hypoxemia, administration of supplemental O2 is beneficial. Occasionally, frank respiratory failure develops, and appropriate supportive measures are instituted (see Chapter 29).

Initial Management Strategies Based on Clinical Setting of Pneumonia

Community-Acquired Pneumonia

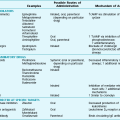

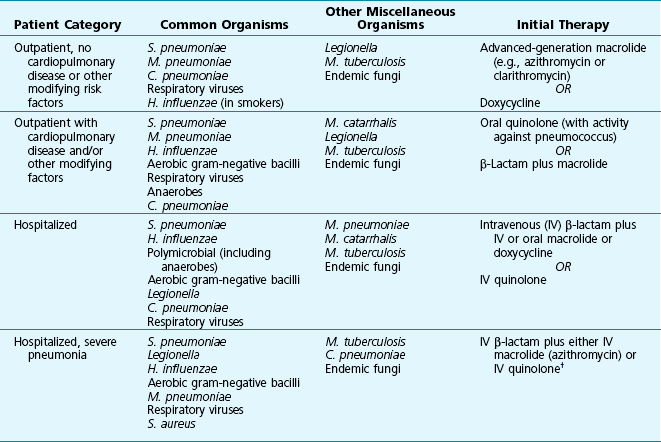

Table 23-1 summarizes the etiology and initial management of four broad subcategories of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. The first group comprises patients who do not have coexisting cardiopulmonary disease or other modifying risk factors, who have not used antibiotics in the previous 3 months, and who do not require hospitalization. The most common pathogens in this group of patients include S. pneumoniae, M. pneumoniae, C. pneumoniae, respiratory viruses, and in smokers, H. influenzae. The preferred therapeutic regimen is one of the advanced-generation macrolide antibiotics such as azithromycin or clarithromycin.

Table 23-1

ETIOLOGY AND INITIAL MANAGEMENT OF COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA*

*Excludes patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection.

†If high risk for Pseudomonas, adjust regimen to include two antipseudomonal agents.

Adapted from Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Thoracic Society: Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults, Clin Infect Dis 44(Suppl 2):S27–S72, 2007.

The third and fourth groups differ from the first two on the basis of severity of the pneumonia. The third group is defined by a need for hospitalization. The fourth group includes patients with the most severe disease, that which necessitates admission to an intensive care unit (ICU). These patients still commonly have pneumonia caused by S. pneumoniae or the other organisms found in outpatients, but with additional concern for gram-negative bacilli, Legionella, and sometimes S. aureus. Therapy for these patients is adjusted accordingly (see Table 23-1). Antibiotics such as a quinolone or an advanced-generation macrolide plus a β-lactam (particularly a third-generation cephalosporin), a carbapenem, or an extended-spectrum penicillin with β-lactamase inhibitor are typically used in these settings, sometimes in combination with vancomycin.

Nosocomial (Hospital-Acquired) Pneumonia

Organisms of particular concern in patients who develop hospital-acquired pneumonia are enteric gram-negative bacilli and S. aureus, but other organisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Legionella can be involved. Diagnostic evaluation is difficult and often complicated by the need to distinguish bacterial colonization of the tracheobronchial tree from true bacterial pneumonia. The clinical issues involved with diagnostic testing and optimal forms of therapy are beyond the scope of this discussion but can be found in the references at the end of this chapter.

American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:388–416.

Bartlett, JG. Diagnostic tests for agents of community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 4):S296–S304.

Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. A randomized trial of diagnostic techniques for ventilator-associated pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2619–2630.

Chastre, J, Fagon, J-Y. Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:867–903.

Durrington, HJ, Summers, C. Recent changes in the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults. BMJ. 2008;336:1429–1433.

Fine, MJ, Auble, TE, Yealy, DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:243–250.

Herzig, SJ, Howell, MD, Ngo, LH, et al. Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2009;301:2120–2128.

Kollef, MH. Prevention of hospital-associated pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1396–1405.

Leong, JR, Huang, DT. Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86:1409–1429.

Lim, WS, van der Eerden, MM, Laing, R, et al, Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax 2003;58:377–382. http://ajrccm.atsjournals.org/cgi/ijlink?linkType=ABST&journalCode=thoraxjnl&resid=58/5/377

Lim, WS, Baudouin, SV, George, RC, et al. BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Pneumonia Guidelines Committee of the BTS Standards of Care Committee. Thorax. 2009;64(Suppl 3):iii1–ii55.

Lorente, L, Blot, S, Rello, J. New issues and controversies in the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:870–876.

Mandell, LA, Wunderink, RG, Anzueto, A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–S72.

Mizgerd, JP. Acute lower respiratory tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:716–727.

Niederman, M. In the clinic. Community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Intern Med. 151, 2009. ITC4-2-ITC4-14

Niederman, MS. Recent advances in community-acquired pneumonia: inpatient and outpatient. Chest. 2007;131:1205–1215.

Porzecanski, I, Bowton, DL. Diagnosis and treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2006;130:597–604.

Waterer, GW, Rello, J, Wunderink, RG. Management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:157–164.

Pneumonia Caused by Specific Organisms

Burillo, A, Bouza, E. Chlamydophila pneumonia,. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2010;24:61–71.

Cunha, BA. Legionnaires’ disease: clinical differentiation from typical and other atypical pneumonias. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2010;24:73–105.

Dockrell, DH, Whyte, MKB, Mitchell, TJ. Pneumococcal pneumonia. Mechanisms of infection and resolution. Chest. 2012;142:482–491.

File, TM. Streptococcus pneumoniae and community-acquired pneumonia: a cause for concern. Am J Med. 2004;117(suppl 3A):39S–50S.

Gupta, SK, Sarosi, GA. The role of atypical pathogens in community-acquired pneumonia. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85:1349–1365.

Hall, CB. Respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1917–1928.

Hammerschlag, MR. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2001;14:181–186.

Harwell, JI, Brown, RB. The drug-resistant pneumococcus. Clinical relevance, therapy, and prevention. Chest. 2000;117:530–541.

Kaye, MG, Fox, MJ, Bartlett, JG, et al. The clinical spectrum of Staphylococcus aureus pulmonary infection. Chest. 1990;97:788–792.

Lednicky, JA. Hantaviruses. A short review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:30–35.

Mansel, JK, Rosenow, EC, III., Smith, TF, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Chest. 1989;95:639–646.

Marik, PE. Aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:665–671.

Peiris, JS, Yuen, KY, Osterhaus, AD, et al. The severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2431–2441.

Ruuskanen, O, Lahti, E, Jennings, LC, et al. Viral pneumonia. Lancet. 2011;377:1264–1275.

Stout, JE, Yu, VL. Legionellosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:682–687.

van der Poll, T, Opal, SM. Pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia. Lancet. 2009;374:1543–1556.

Wiedemann, HP, Rice, TW. Lung abscess and empyema. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;7:119–128.

Whitney, CG, Farley, MM, Hadler, J, et al. Increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Program of the Emerging Infections Program Network. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1917–1924.

Wilson, R, Dowling, RB. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other related species. Thorax. 1998;53:213–219.

Writing Committee of the Second World Health Organization Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Human Infection with Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus. Update on avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infection in humans. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:261–273.

Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1708–1719.

Respiratory Infections Associated with Bioterrorism

Bellamy, RJ, Freedman, AR. Bioterrorism. QJM. 2001;94:227–234.

Bush, LM, Abrams, BH, Beall, A, Johnson, CC. Index case of fatal inhalational anthrax due to bioterrorism in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1607–1610.

Centers for Disease Control. Recognition of illness associated with the intentional release of a biologic agent. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:893–897.

Inglesby, TV, O’Toole, T, Henderson, DA, et al. Anthrax as a biological weapon, 2002. Updated recommendations for management. Working Group on Civilian Biodefense. JAMA. 2002;287:2236–2252.

Prentice, MB, Rahalison, L. Plague. Lancet. 2007;369:1196–1207.

Swartz, MN. Recognition and management of anthrax—an update. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1621–1626.

Sweeney, DA, Hicks, CW, Cui, X, et al. Anthrax infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1333–1341.