Tuberculosis and Nontuberculous Mycobacteria

Now more than 125 years since identification of the tubercle bacillus by Robert Koch in 1882, we still cannot become complacent about the disease. It has been estimated that approximately one third of the world’s current population, or over 2 billion people, have been infected (i.e., have either latent or active infection) with the tubercle bacillus, with 8 to 10 million new cases of active tuberculosis and approximately 2 to 3 million deaths occurring worldwide each year. The overwhelming majority of cases of active tuberculosis occur in developing countries. Some 70 million of the 88 million cases of tuberculosis during the 1990s were from Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where coinfection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a major contributor to the increase in infections. Tuberculosis remains an important public health problem in the United States, particularly in indigent and immigrant populations and patients with AIDS (see Chapter 26). Reported cases of tuberculosis in the United States were decreasing until the mid-1980s, at which time the AIDS epidemic and immigration from countries with a high prevalence of tuberculosis combined to result in an increasing frequency of cases. Fortunately, since 1991 the number of cases reported annually in the United States has again been decreasing. Perhaps most alarming, both in the United States and throughout the world, is the relatively recent emergence of drug-resistant strains of the organism, some of which are resistant to multiple antituberculous drugs.

Diagnostic Approach

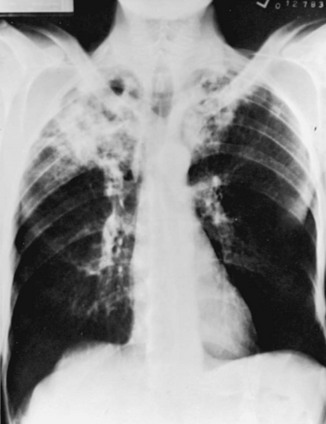

With reactivation tuberculosis, the most common sites of disease are the apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes and, to a lesser extent, the superior segment of the lower lobes. A variety of patterns can be seen: infiltrates, cavities, nodules, and scarring and contraction (Fig. 24-1). The presence of abnormal findings on a chest radiograph does not necessarily indicate active disease. The disease may be old, stable, and currently inactive, and it is difficult, if not impossible, to gauge activity on the basis of radiographic appearance.

Nontuberculous Mycobacteria

The nontuberculous mycobacteria are primarily responsible for disease in two settings: (1) the patient with underlying lung disease, in whom local host defense mechanisms presumably are impaired, and (2) the patient with a defect in systemic immunity, particularly AIDS (see Chapter 26). Nevertheless, these organisms cause disease in a small number of patients without either of these risk factors. Overall recognition of disease from nontuberculous mycobacteria has increased over the past 10 to 20 years, in large part because of its occurrence in patients with AIDS.

American Thoracic Society. Diagnostic standards and classification of tuberculosis in adults and children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1376–1395.

Anadash, A, Dheda, K, Keane, J, et al. Novel developments in the epidemic of human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis coinfection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:987–997.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends in tuberculosis incidence—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:333–337.

Connell, DW, Berry, M, Cooke, G, Kon, OM. Update on tuberculosis: TB in the early 21st century. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20:71–84.

Escalante, P. In the clinic: tuberculosis. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:ITC610–614.

Lawn, SD, Zumla, AI. Tuberculosis. Lancet. 2011;378:57–72.

Yew, WW, Leung, CC. Update in tuberculosis 2007. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:479–485.

Barnes, PF, Cave, MD. Current concepts: molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1149–1156.

Quast, TM, Browning, RF. Pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of pulmonary tuberculosis. Dis Mon. 2006;52:413–419.

Schluger, NW. The pathogenesis of tuberculosis: the first one hundred (and twenty-three) years. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:251–256.

Schluger, NW, Rom, WN. The host immune response to tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:679–691.

Schwander, S, Dheda, K. Human lung immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis: insights into pathogenesis and protection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:696–707.

Smith, I, Nathan, C, Peavy, HH. Progress and new directions in genetics of tuberculosis: an NHLBI working group report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1491–1496.

van Crevel, R, Ottenhoff, TH, van der Meer, JW. Innate immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis,. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:294–309.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Approach

Alvarez, S, McCabe, WR. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis revisited: a review of experience at Boston City and other hospitals. Medicine. 1984;63:25–55.

American Thoracic Society. Diagnostic standards and classification of tuberculosis in adults and children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1376–1395.

American Thoracic Society. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:S221–S247.

Dosanjh, DPS, Hinks, TSC, Innes, JA, et al. Improved diagnostic evaluation of suspected tuberculosis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:325–336.

Gopi, A, Madhavan, SM, Sharma, SK, Sahn, SA. Diagnosis and treatment of tuberculous pleural effusions in 2006. Chest. 2007;131:880–889.

Horsbaugh, CR, Rubin, EJ. Clinical practice: Latent tuberculosis infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1441–1448.

Jacob, JT, Mehta, AK, Leonard, MK. Acute forms of tuberculosis in adults. Am J Med. 2009;122:12–17.

Lalvani, A. Diagnosing tuberculosis infection in the 21st century. New tools to tackle an old enemy. Chest. 2007;131:1898–1906.

Schluger, NW. Changing approaches to the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:2020–2024.

Schluger, NW, Burzynski, J. Recent advances in testing for latent TB. Chest. 2010;138:1456–1463.

Weir, MR, Thornton, GF. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Med. 1985;79:467–478.

American Thoracic Society. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:S221–S247.

American Thoracic Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treatment of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:603–662.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with extensive resistance to second-line drugs—worldwide, 2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:301–305.

Cohn, DL. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Semin Respir Infect. 2003;18:249–262.

Jasmer, RM, Nahid, P, Hopewell, PC. Latent tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1860–1866.

Leung, CC, Rieder, HL, Lange, C, Yew, WW. Treatment of latent infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis: update 2010. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:690–711.

Nahid, P, Gonzalez, LC, Rudoy, I, et al. Treatment outcomes of patients with HIV and tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1199–1206.

Richeldi, L. An update on the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:736–742.

Small, PM, Fujiwara, PI. Management of tuberculosis in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:189–200.

World Health Organization. Treatment of tuberculosis guidelines, 4th edition. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241547833_eng.pdf, 2010. Accessed July 17, 2012

Yew, WW, Lange, C, Leung, CC. Treatment of tuberculosis: Update 2010. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:441–462.

American Thoracic Society, Infectious Disease Society of America. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367–416.

Ellis, SM, Hansell, DM. Imaging of non-tuberculous (atypical) mycobacterial pulmonary infection. Clin Radiol. 2002;57:661–669.

Field, SK, Fisher, D, Cowie, RL. Mycobacterium avium complex pulmonary disease in patients without HIV infection. Chest. 2004;126:566–581.

Glassroth, J. Pulmonary disease due to nontuberculous mycobacteria. Chest. 2008;133:243–251.

Holland, SM. Nontuberculous mycobacteria. Am J Med Sci. 2001;321:49–55.

Jones, D, Havlir, DV. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in the HIV infected patient. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:665–674.

Zumla, AI, Grange, J. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infections. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:369–379.