CHAPTER 185 Plagiocephaly

In the past several years, the incidence of nonsynostotic plagiocephaly has increased significantly, and it is believed to be a result of the Back to Sleep campaign of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), in which a supine sleeping position is recommended to reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).1–3 The AAP recognized studies from the late 1980s finding that there was a greater incidence of SIDS associated with infants sleeping in the prone position. Recommendations were circulated regarding the need to avoid the prone sleeping position in infants, and the frequency of plagiocephaly began to increase. In April 1992, the AAP issued an official recommendation that all parents be advised that infants should sleep in the supine position to prevent SIDS. The incidence of SIDS has been reported to have decreased by nearly 40% since the advent of the Back to Sleep campaign, whereas the incidence of positional plagiocephaly has increased by 600%.4

History

Throughout history, there has been evidence of intentional cultural head molding. People of ancient cultures have modified the shape of their infants’ heads using head wraps or positional devices to achieve a shape that was preferable to them. Ancient Egyptians used head binding to produce a cosmetically pleasing and fashionable elongation of skull shape. Deformation of the skull by pressure to an infant’s head dates back to 2000 BC. Reviews of the medical and anthropologic literature and examinations of anthropologic collections have found evidence of cranial deformation. Conclusions drawn by these reviews indicate that there does not appear to be any evidence of negative effect on the societies that have practiced even very severe forms of intentional cranial deformation (e.g., the Olmec and Maya). Some contemporary civilizations have practiced various forms of intentional and unintentional cranial deformation as well as prehistoric ones.5,6

The same occurrence of unintentional head shape deformity that faces infants today has been present for ages, although we believe that interventions for SIDS may be increasing today’s incidence over that of previous times. Recent publications indicate that the incidence of plagiocephaly seen by pediatric neurosurgeons has greatly increased since the late 1980s and has been directly related to sleep position recommendations for infants to prevent SIDS. During the time that prevalence of occipital plagiocephaly was increasing, there was clearly controversy over the pathogenesis of the misshapen occiput. The disorder was thought to be secondary to lambdoid suture synostosis, partial fusions, or even “sticky sutures.”7 Lambdoid suture abnormalities do play a role in causing synostotic plagiocephaly, but they a rare.8 Many infants with nonsynostotic plagiocephaly may have been managed with surgical reconstruction, especially during the time period when identifying that most children with plagiocephaly were not harboring lambdoid synostosis.9,10 As it became clear that the asymmetry was largely due to positional, gravitational forces, attempts were made to treat the deformation with external orthotic devices and avoid surgery unless clearcut evidence was found for synostosis. Surgery was reserved for those who failed conservative interventions. Many external cranial orthotic devices were devised. As these devices became more expensive and their results appeared to be incomplete in restoring normal head shape, other interventions were devised, including infant repositioning, physical therapy, and treatment of torticollis. Devices to aid the repositioning of the infant and other investigational techniques have been used. Controversy exists over the optimal treatment because reproducible, consistent success has not been found with any treatment as yet.

Scope and Impact

The scope and impact of this problem of plagiocephaly for today’s infants are extensive. The fact that plagiocephaly is occurring more frequently in today’s children is evident by the fact that the entity has been infrequently reported in journals and is absent from most medical texts from 25 years ago. Few infants received treatment before the late 1970s.10 Great concerns arise for parents of infants with significant head shape deformity. Many health care dollars are spent annually attempting to correct the asymmetry. Multiple physician visits are made, imaging studies obtained, expensive orthotic devices applied, and physical therapies instituted, and these interventions, along with occasional litigation of treatment failures, have multiplied the costs of what appears to be a benign disorder. Developers of proprietary devices compete for a portion of health care dollars spent in attempts to correct this deformity. Some children undergo surgical procedures similar to those used for craniosynostosis with the accompanying risks and morbidity. Research studies and publications have indicated that there may also be health concerns secondary to plagiocephaly occurring in the form of developmental delay and ocular, auditory, and mandibular pathology.11–14

Incidence

Estimates indicate that 1 of every 60 neonates may have some degree of plagiocephaly or brachycephaly today.15,16 The incidence of plagiocephaly in children has increased dramatically since the early 1990s and has been correlated with the practice of maintaining infants in the supine position.4,16 Plagiocephaly is common among otherwise normal patients whose parents are unaware of their condition.10 The incidence of plagiocephaly in infants with congenital disorders such as congenital hip dislocation, bat ears, congenital scoliosis, and sternomastoid tumors and torticollis has been reported to be 60%, decreasing to 32% by adolescence. Forty-eight percent of normal healthy infants younger than 1 year had significant degrees of asymmetry, as did 14% of the normal adults.17

Pathogenesis and Pathology

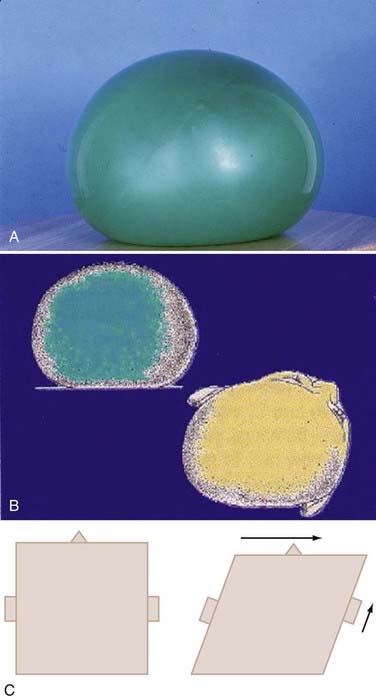

The most common scenario whereby infants develop plagiocephaly involves positioning for sleep when they go home from the hospital after delivery. The infant is usually placed in the same position each night and other times that they sleep. The infant may turn its head toward the activity in the room. The child may have a preference of head turning secondary to neck tightness (torticollis) from perinatal causes. For what ever reason flatness is present, from birth or within the first month, a flat area develops behind one ear. Gravitational forces tend to further flatten the head. These forces are able to deform the skull rapidly owing to the mobility of the sutures and plasticity of the brain. These loose sutures allow for extensive head shape changes during delivery and passage of the head through the birth canal. The ability of the sutures to shift decreases quite rapidly during the first 2 months of life. A good example of gravitational deformation of the infant head is demonstrated by the shape changes seen in a balloon filled with water resting on a flat surface in Figure 185-1A.The bottom of the balloon becomes very flat. The top of the balloon flattens but to a lesser degree. The sides bulge but also sag, creating an asymmetric bulge in the sides of the balloon. Once the flatness of the skull begins, the infant’s head naturally rolls toward the flat spot, pulled by gravity, and it takes significant effort for the infant to hold the head in a neutral position. For the first 5 to 6 months, the flatness continues to increase. There is a compensatory asymmetry that is seen in the entire skull base, resulting in shift of ears, mandible, and orbits (Fig. 185-1B). The anterior cranial fossa also shows asymmetry. There is a parallelogram effect that explains the shift of the skull base (Fig. 185-1C). As the flatness begins on one side of the occiput, the occipital bone structures are pushed to the opposite side, resulting in a protrusion of the contralateral occipital structures. The frontal skull is misshapen because gravitational forces are acting in a greater force to the highest surface of the skull, and as gravity flattens the area contralateral to the occipital flatness, a similar shift of bony structures occurs in the forehead, resulting in a frontal protrusion. The sides of the head tilt toward the side of occipital flatness, and the shift to that side causes the ears to appear misaligned. In fact, the shift of structures in this manner involves the entire skull base, and thus there is shift of facial features, mandible, and orbits. When the infant begins to move and change position during sleep times and begins to roll over and spend more time upright, the progression of asymmetry arrests and over the next several months begins to correct itself by normal continued head growth. Seldom, however, will the asymmetry completely resolve. Studies have shown persistent asymmetry up to age 5 years.18 I re-examined more than 300 children treated for plagiocephaly 3 to 5 years after treatment and found the cranial vault asymmetry to average 5.4 mm. Asymmetry is occasionally found to persist into adulthood.

Other, less frequent causes of asymmetry include multiple pregnancies, in which multiple infants share a restricted space in the womb and forces on the head are constant because of lack of room for the fetus to reposition.19 This restricted space in the womb also contributes to prenatal torticollis, thus complicating the ability to reposition the infant after delivery. Uterine malformations may contribute to the development of fetal plagiocephaly.19,20 These infants are born with various types of deformation of the cranium. Many exhibit a form of “cranial scoliosis,” appearing like a “windswept” deformity in which the vertex of the cranium is pushed off to one side above the ears. These children usually exhibit associated variations of torticollis in which the neck is tilted to the side. This form of torticollis is difficult to correct because the muscle, ligaments, and at times, bones have grown in an asymmetric manner. The inverted position of the fetus with the head resting against bony prominences in the mother’s pelvis can also result in asymmetry. The development of plagiocephaly is more likely in the presence of torticollis. Torticollis is also presumed to occur because of neck position and stretch to the cervical musculature and ligaments during delivery, resulting in a painful “wry” neck.

Viral illnesses in the first month of life may result in a wry neck and torticollis. Torticollis may also result from constant preference of the infant to turn its head to only one side and then further add to the difficulty of repositioning later to correct the deformity. A retrospective study found that 95% of referrals for torticollis presented with plagiocephaly or facial asymmetry. The authors concluded that torticollis was secondary to plagiocephaly in 88% of patients.21

Prematurely born infants often develop various types of deformational skull deformity. These may be occipital plagiocephaly but usually result in scaphocephaly or dolichocephaly owing to the need to maintain airway for ventilation, which required the head be placed in a side-to-side position. Premature infants have even greater plasticity of skull and brain, and positional deformity can occur rapidly. Children with delayed neurological development or perinatal or infant brain injury due to infarction or trauma develop plagiocephaly many times owing to constant positioning in one direction or lack of head turning and activity.22 They remain in the supine position for greater lengths of time. Infants with neurological deficits due to brain development problems or perinatal injury may show a preference for turning their head to one side over the other owing to spasticity, dystonia, weakness, or neglect syndromes. Occipital flatness may occur on one side or the other, or the occiput may become symmetrically flat, depending on in what position the infant’s head remains. Treatment and reversal of this form of plagiocephaly are more difficult in these children because they are usually less likely to begin to increase their mobility to remain off the flat area because of their deficits. Furthermore, infants with hydrocephalus who undergo ventriculoperitoneal shunting are at increased susceptibility to deformational plagiocephaly due to the loss of physiologic maintenance of their cerebrospinal fluid dynamics.

Some studies have reported that plagiocephaly may cause developmental delay. One study reported that 39.7% of patients with persistent deformational plagiocephaly had received special educational services. Their siblings were used as controls and were found to have only a 7.7% incidence of receiving special educational services.23 Another study reported that mental developmental index and the psychomotor developmental index scores were significantly different from the expected norms in plagiocephalic children evaluated with Bayley Scales of Infant Development II. In this study, 8.7% of children were categorized as severely delayed on the mental development index, compared with the expected normal population occurrence of 2.5%.24,25 These studies have not indicated that delays persisted into adulthood. These studies suggest an association between plagiocephaly and developmental delay; they cannot determine a causal effect. For example, it is possible that children with preexisting development delays or weakness are likely to remain in one position for extended periods of time, increasing their risk for plagiocephaly. I have not seen such a high incidence of developmental delays consistent with these reports. Another review assessed the neurological profile of 49 infants ranging in age from 4 months to 13 months with nonsynostotic plagiocephaly, compared with 50 age-matched concurrent controls. There was no difference between the groups on the overall Hammersmith infant neurological assessment.26

Ophthalmologic findings of unilateral or bilateral astigmatism have been reported in 24% of patients with plagiocephaly compared with 19% prevalence in the normal population.12 Infants with plagiocephaly exhibited smaller amplitudes in responses recorded in auditory event–related potentials compared with controls.11 It is not clear in these studies whether developmental delay preceded the development of plagiocephaly given that delayed children have a higher incidence of developing plagiocephaly and would be expected to have increased auditory and ophthalmologic abnormalities. The relationship between plagiocephaly in infants and long-term health outcomes remains unclear.13,24

Evaluation of the Infant with Plagiocephaly

Infants with asymmetry to the cranium are often referred to the neurosurgeon by the primary care physician to assess the cause of the asymmetry.27–29 Craniosynostosis must be diagnosed early and is generally treated surgically. Early diagnosis of fused sutures allows early correction through surgical procedures, and generally the outcomes are better when these deformities are corrected at an earlier age. Several imaging studies have been useful in identifying these infants with synostosis. Skull radiographs usually suffice to identify closed sutures and differentiate synostotic from nonsynostotic plagiocephaly. Although there have been descriptions of sutural synostoses identified using cranial ultrasound and radionuclide studies, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) remain the current definitive studies to identified fused sutures. Three-dimensional reconstructions of the skull are helpful in the identification of synostosis. Many neurosurgeons develop the ability to identify nonsynostotic plagiocephaly by clinical appearance and physical examination. In these cases, infants are treated for plagiocephaly and are only imaged after failure of improvement of asymmetry with nonoperative treatment and observation time.

Lambdoid synostosis may result in asymmetry similar to nonsynostotic plagiocephaly. The incidence of lambdoid synostosis is low compared with other forms of synostosis. Only 1 of 115 patients with plagiocephaly was found to have lambdoid synostosis in one prospective study.30 Another study found lambdoid synostosis in 5.5% of patients in a population of infants born with any type of craniosynostosis.10,31 Another study from Minnesota indicated that confirmed and suspected craniosynostosis occurred in 3.1 and 13.6 cases per 10,000 births, respectively.32 These studies indicate that isolated lambdoid synostosis should occur about 3 times in 100,000 births (0.003%, or about 100 times less frequently than myelomeningocele).10 In the recent past, operations to correct lambdoid synostosis were performed more frequently than they are today, possibly indicating that some have treated deformational plagiocephaly with surgical correction. In a review of cases managed for craniosynostosis at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto between 1972 and 1984, 18% of patients were reported to have premature closure of the lambdoid suture.33 Rekate reviewed several studies and suggested that the difference in incidence appears to reflect the authors’ definition of lambdoid craniosynostosis.10 In only 3 of the 74 patients operated on for lambdoid synostosis was the suture found to be pathologically fused. If incidence is recalculated on the basis of this conclusion, pathologically distinct lambdoid craniosynostosis occurred in 3 of 333 children with craniosynostosis, or less than 1% of craniosynostosis treated at that institution.

Various studies have attempted to quantify the asymmetry using measuring techniques, imaging studies, and computer-assistive devices.34–41 There has been no single method identified that is consistently reproducible and accurate, making the investigation of various treatment paradigms impossible to compare to identify the best overall treatment. Techniques used to quantify asymmetry of the infant’s head in the neurosurgeon’s daily clinical practice must be simple and cost-effective. At best, these methods are likely to have variations from observer to observer depending on the individual obtaining the measurement. Many publications have shown various anthropometric points on the skull for which measurement can be made and compared from different skulls. Specialists in anthropology practice these measurement techniques; however, they are not often practiced on living subjects with soft tissue mobility, making the measurements much more difficult. These descriptions and measurements can become complex, and again, they may be difficult to make and exhibit inconsistency from observer to observer. Measurements are made more difficult when they are made in the clinical setting. The infant’s hair and scalp cause the accuracy of measurements to decline, especially if there is difficulty in getting the subject to remain immobile during the measurement. One study evaluated differences in measurements made by different observers and found variability of cranial vault asymmetry (CVA) by a mean of 2.2 mm with a standard deviation of 6.5 mm.42 The authors concluded that measurements used in these anthropometric assessments may be unreliable. They further noted that identifying the posterior landmarks (the most prominent part of the occiput and the flattest part) for measurement of CVA is somewhat subjective.

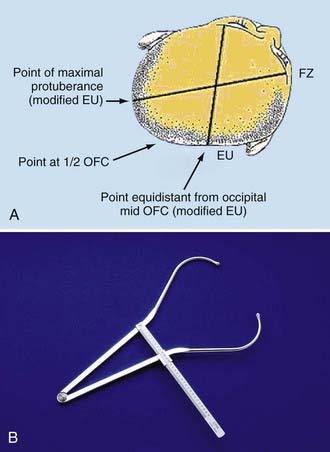

I have found it efficacious to obtain cross-diagonal measurements to determine CVA (Fig. 185-2A). Large calipers are placed at the frontozygomaticus (FZ) and modified euryon (EU) points to measure the difference in length as an indication of asymmetry to assess comparative changes. The FZ point is more easily identified because of the lateral supraorbital bony prominence present in most infants. The contralateral point on the parietal bone is more difficult because of lack of a fixed prominence or palpable reference point. The first measurement is made to measure the long axis of the plagiocephaly to capture the longest measurement possible on the side opposite the flat occiput. Calipers are placed on the FZ point and moved over the prominent occipital bulge made by the plagiocephaly. This defines a “modified” EU point. The midpoint of occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) is marked on the occiput to determine the second parietal point equidistant to the contralateral parietal-occipital point for the opposite cross-diagonal measurement. As shown in Figure 185-2, the occipital point of reference must be chosen as a point equidistant from the midline in the axial plane of the infant’s head. These measurements can be quickly done in the clinical setting to help judge changes in head asymmetry. The changes can be followed by simply recording the difference in length of the long and short axis of the head. To account for OFC changes and differences, the measurement can be expressed as a ratio by calculating the short axis divided by the long axis measurement.

Infants with brachycephaly can be thought of as simply having bilateral plagiocephaly. Medical dictionaries and anthropologic sources define brachycephaly as a cranial index (cranial index = width ÷ length × 100%) greater than 81%.43 Measurement in these children is done by recording anteroposterior and biparietal lengths. The same problems exist in accurately quantifying cranial index in these patients as those described previously.

Treatment

Treatment of underlying or associated torticollis is beneficial to prevent further positional deformity and to aid in treatment of plagiocephaly whether through repositioning techniques or use of cranial orthotic devices. Infants with rotational torticollis may benefit from physiotherapy referrals. I teach the parents to place the infant supine and slowly rotate the head and neck to the opposite side of the torticollis bringing the chin within 1 to 2 cm of the shoulder, as shown in Figure 185-3. The child is allowed to raise the opposite shoulder if desired to prevent undue stresses on the neck. This maneuver is recommended to be performed for 1 full minute several times daily for as long as it takes for the infant to easily move the head to either side equally without discomfort. The usual length of time for cervical physiotherapy to show resolution of tightness and neck turning preference is 3 to 4 weeks. Neck stretching exercises are used at the same time as repositioning or cranial orthotic treatment. Improvement in head shape asymmetry has been reported by repositioning the infant head to allow gravitational forces to act in the opposite direction that is believed to have caused the deformity. Active counter-positioning treatment of deformational occipital plagiocephaly has been described.44,45 Repositioning of the infant is accomplished by turning the infant a “quarter-turn” to the side or to a “half-supine” position opposite the occipital flattening by placing a blanket roll or other positioning device behind the infant’s torso (not head) such that the baby’s head rests on the protuberant side away from the flat area on the occiput. The gravitational pressures that readily flattened the skull initially may then begin to exert forces on the protuberance to flatten that area, shifting the skull back into normal position. Placing the blanket roll or positioning device directly on the mattress under the bedding more easily prevents the child from pushing the propping device away. A second blanket roll may be used in front of the infant placed in front of the chest and abdomen to maintain the child from turning into the prone position. This “saddle” allows for the child to be more easily maintained in the position that applies the greatest gravitational pressure to the deformity on the occiput. Some investigators have advocated supervised “tummy time” in the prone position to reduce the asymmetry of the head. One must remember that the child must be encouraged to turn the head such that the long axis of the deformity is perpendicular to gravitational forces. For example, an infant with left occipital plagiocephaly (flatness on the left occiput) should be turned to the right when supine, and the head should also be turned to the right when resting in the prone position during “tummy time.” When children are placed in an infant bed, they may have a tendency to turn toward activity in the room; thus, it would be beneficial to change the bed position or how the infant is placed in the bed to promote turning the head in the desired direction to either reduce or prevent plagiocephaly.

FIGURE 185-3 Photographs of child against repositioning device (A) and in neck stretching exercise (B).

In 1996, the Task Force on Infant Positioning and SIDS provided an update to the June 1992 AAP policy, Infant Positioning and SIDS, which recommended that healthy term infants be placed on their sides or backs to sleep. They indicated that new data suggested that the supine position confers the lowest risk; however, the side position is still significantly safer than the prone position.46 The AAP Task Force on SIDS changed this concept, stating that the AAP no longer recognizes side sleeping as a reasonable alternative to fully supine sleeping and also stressed the need to avoid redundant soft bedding and soft objects in the infant’s sleeping environment. They stressed the importance of educating secondary caregivers and neonatology practitioners on the importance of the Back to Sleep program and strategies to reduce the incidence of positional plagiocephaly associated with supine positioning.47 This latest recommendation could also be construed to include repositioning as well as cranial orthotic devices.

Improvement in head shape asymmetry has been reported by the use of external orthotic devices (e.g., helmets, head bands, and cupping devices). The manner in which the devices achieve improvement in the head shape is not clear. They have been described to achieve better symmetry through the molding device by leaving extra room over the flat area of skull for the head to grow into a better shape. When pressure is applied to the skull with active cranial orthotic devices (e.g., Velcro, rubber bands), complications of scalp compression occur (e.g., blisters, pressure sores). I believe that these orthotic devices provide a round surface for the back of the infant’s head to roll more easily from side to side and prevent the head from simply rolling to the flat spot on the occiput, thus allowing gravitational forces to round out the occipital plagiocephaly. Studies comparing their effectiveness with that of repositioning treatments found that the devices had better outcomes.48–51 Other studies have shown no difference in treatment with cranial orthotic devices compared with repositioning.18,45 Another study showed improved outcomes with repositioning over orthotic treatment.52 Most importantly, when these studies are all reviewed, the data uniformly show that asymmetry persists long after treatment, and no study has shown that these treatments result in satisfactory consistent elimination of cranial vault asymmetry caused by plagiocephaly. Controversy remains regarding the use of orthotic devices compared with repositioning techniques. Reviewers have found technical difficulties with these comparative studies regarding randomization, control populations, and measurements and have pointed out that it may be very difficult to design a study that accurately compares the available devices and treatments. They further indicated that results should be interpreted with caution because of commercial interests by some of the investigators.50 In 2007, the National Health Service Quality Improvement Scotland issued an Evidence Note on the use of cranial orthosis treatment for infant deformational plagiocephaly, stating that no evidence-based conclusions could be reached because of the limited methodologic quality of the available trials.53,54

Comparison of cost of orthotic treatment to that of repositioning treatment is the one factor that is significantly divergent, with the cost of cranial orthotic treatment often approaching the cost of surgeries for the same condition. Comparison studies have been made to assess the outcomes of orthotic devices and repositioning techniques and remain inconclusive. I have followed children with the aforementioned measurement techniques for almost 20 years. Mild to moderate asymmetry has been defined as 9 to 12 mm of cross-diagonal cranial vault asymmetry. Greater than 12 mm has been defined as moderate to severe asymmetry. Initial studies demonstrated that the infants with mild to moderate asymmetry had the same amount of correction at the end of treatment regardless of treatment choice. Infants with asymmetry greater that 12 mm had a slightly better outcome with orthotic treatment.45 Later follow-up of these infants 3 to 5 years after treatment showed that the asymmetries in the repositioned group and in the orthotically treated group remain similar without clear distinction as to the better treatment. More important, these later follow-up studies showed that persistent asymmetry, averaging about 5.4 mm, exists in both treatment groups of children. Hence, treatment to completely reverse the asymmetry of plagiocephaly has not yet been described.

Conclusion

The health outcomes of untreated nonsynostotic plagiocephaly are uncertain. There are no published data showing that plagiocephaly caused the neuropsychological deficits, developmental delay, temporomandibular joint disorders, or psychosocial concerns related to a perceived abnormal appearance. The major reason for intervention is to optimize the cranial contour to achieve an acceptable appearance, not to prevent or correct adverse developmental consequences. Remarkably few adults have deformities of cranial symmetry or shape, suggesting that the abnormality is either self-correcting or effectively masked by a combination of increased cranial circumference and hair growth. The available data do not clearly support one treatment technique as superior to another. Moreover, the degree of cranial asymmetry that constitutes an abnormality warranting intervention compared with normal human variation cannot be determined from the available data.15

Medical problems without definitive consistent successful treatment resulting in complete resolution of the disorder often have many variable treatment recommendations without a clear successful cure, which is clearly the case with plagiocephaly in children. The incidence of plagiocephaly in this population has had a strong correlation with the practice of maintaining infant sleep position on the back. The impact of social, economic, and developmental factors is so extensive that, in the lack of definitive successful treatment or complete cure of the disorder, one must conclude that preventive measures during the first 2 months of life is the best method for managing plagiocephaly. Altering positional gravitational forces on the infant’s head during the first 2 months of life will reduce the incidence of plagiocephaly and result in much better long-term outcomes. Plagiocephaly resulting from prenatal factors needs early and aggressive treatment. The AAP Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine Section on Plastic Surgery and Section on Neurological Surgery recommended, “Pediatricians need to be able to properly diagnose skull deformities, educate parents on methods to proactively decrease the likelihood of the development of occipital flattening, initiate appropriate management, and make referrals when necessary.” When infants are discharged to home after delivery, they usually are scheduled for follow-up with their pediatrician or primary care physician 6 weeks to 2 months later. By the time they are seen, the occipital flatness can be considerable and difficult to correct. Referral to specialists and insurance approvals often increase the delay in treatment. It is for this reason that education about plagiocephaly prevention must be coupled with the education for supine sleep positioning that parents receive in caring for their newborn children.55

De Chalain TM, Park S. Torticollis associated with positional plagiocephaly: a growing epidemic. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:411-418.

Kordestani RK, Patel S, Bard DE, et al. Neurodevelopmental delays in children with deformational plagiocephaly. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:207-218.

Miller RI, Clarren SK. Long-term developmental outcomes in patients with deformational plagiocephaly. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E26.

Panchal J, Amirsheybani H, Gurwitch R, et al. Neurodevelopment in children with single suture craniosynostosis and plagiocephaly without synostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1492-1498.

Proctor MR. The Use of Cranial Orthoses for Positional Plagiocephaly. San Jose del Cabo, Mexico: ASPN; February 4-8, 2008.

Scrutton D. Position as a cause of deformity in children with cerebral palsy (1976). Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:404.

1 Argenta LC, David LR, Wilson JA, Bell WO. An increase in infant cranial deformity with supine sleeping position. J Craniofac Surg. 1996;7:5-11.

2 Caccamese J, Costello BJ, Ruiz RL, Ritter AM. Positional plagiocephaly: evaluation and management. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2004;16:439-446.

3 Turk AE, McCarthy JG, Thorne CH, Wisoff JH. The “back to sleep campaign” and deformational plagiocephaly: is there cause for concern? J Craniofac Surg. 1996;7:12-18.

4 Kane AA, Mitchell LE, Craven KP, Marsh JL. FAAP Observations on a recent increase in plagiocephaly without synostosis. Pediatrics. 1996;97:877-885.

5 Bridges SJ, Chambers TL, Pople IK. Plagiocephaly and head binding. Arch Dis Child. 2002;86:144-145.

6 Lekovic GP, Baker B, Lekovic JM, Preul MC. New World cranial deformation practices: historical implications for pathophysiology of cognitive impairment in deformational plagiocephaly. [comment in: J Craniofac Surg 2008;19:292]. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(6):1137-1146.

7 Losee JE, Feldman E, Ketkar M, et al. Nonsynostotic occipital plagiocephaly: radiographic diagnosis of the “sticky suture.”. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1860-1869.

8 Mulliken JB, Vander Woude DL, Hansen M, et al. Analysis of posterior plagiocephaly: deformational versus synostotic. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 1999;103:371-380.

9 Jackson IT, Costanzo C, Marsh WR, Adham M. Orbital expansion in plagiocephaly. Br J Plast Surg. 1988;41:16-19.

10 Rekate HL. Occipital plagiocephaly: a critical review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:24-30.

11 Balan P, Kushnerenko E, Sahlin P, et al. Auditory ERPs reveal brain dysfunction in infants with plagiocephaly. J Craniofac Surg. 2002;13:520-526.

12 Gupta PC, Foster J, Crowe S, et al. Ophthalmologic findings in patients with nonsyndromic plagiocephaly. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:529-532.

13 Siatkowski RM, Fortney AC, Nazir SA, et al. Visual field defects in deformational posterior plagiocephaly. J AAPOS. 2005;9:274-278.

14 St John D, Mulliken JB, Kaban LB, Padwa BL. Anthropometric analysis of mandibular asymmetry in infants with deformational posterior plagiocephaly [erratum in: J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:419]. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:873-877.

15 Blue Cross Blue Shield Association. 1999 TEC Assessment. Tab 21: Technology Evaluation Center Assessments (TEC).

16 Peitsch WK, Keefer CH, LaBrie RA, Mulliken JB. Incidence of cranial asymmetry in healthy newborns. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e72.

17 Watson GH. Relation between side of plagiocephaly, dislocation of hip, scoliosis, bat ears, and sternomastoid tumours. Arch Dis Child. 1971;46:203-210.

18 Steinbok P, Lam D, Singh S, et al. Long-term outcome of infants with positional occipital plagiocephaly. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23:1275-1283.

19 Littlefield TR, Kelly KM, Pomatto JK, Beals SP. Multiple-birth infants at higher risk for development of deformational plagiocephaly. II. Is one twin at greater risk? Pediatrics. 2002;109:19-25.

20 Proctor MR. The Use of Cranial Orthoses for Positional Plagiocephaly. San Jose del Cabo, Mexico: ASPN; February 4-8, 2008.

21 de Chalain TM, Park S. Torticollis associated with positional plagiocephaly: a growing epidemic. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:411-418.

22 Scrutton D. Position as a cause of deformity in children with cerebral palsy (1976). Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:404.

23 Miller RI, Clarren SK. Long-term developmental outcomes in patients with deformational plagiocephaly. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E26.

24 Kordestani RK, Patel S, Bard DE, et al. Neurodevelopmental delays in children with deformational plagiocephaly. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:207-218.

25 Panchal J, Amirsheybani H, Gurwitch R, et al. Neurodevelopment in children with single suture craniosynostosis and plagiocephaly without synostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1492-1498.

26 Fowler EA, Becker DB, Pilgram TK, et al. Neurologic findings in infants with deformational plagiocephaly. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:742-747.

27 Ehret FW, Whelan MF, et al. Differential diagnosis of the trapezoid-shaped head. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;41(1):13-19.

28 Huang MHA, Gruss JS, Clarren SK, et al. The differential diagnosis of posterior plagiocephaly: true lambdoid synostosis versus positional molding. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 1996;98:765-774.

29 Huang MHS, Mouradian WE, Cohen SR, Gruss JS. The differential diagnosis of abnormal head shapes: separating craniosynostosis from positional deformities and normal variants. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1998;35:204-211.

30 Mulliken JB, Vander Woude DL, Hansen M, et al. Analysis of posterior plagiocephaly: deformational versus synostotic. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 1999;103:371-380.

31 Shuper A, Merlob P, Grunebaum M, et al. The incidence of isolated craniosynostosis in the newborn infant. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139:85-86.

32 French LR, Jackson IT, Melton LJIII. A population-based study of craniosynostosis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:69-73.

33 Muakkassa KF, Hoffman HJ, Hinton DR, et al. Lambdoid synostosis. Part 2. Review of cases managed at the Hospital for Sick Children, 1972-1982. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:340-347.

34 Chang PY, Chien YW, Huang FY, et al. Computer-aided measurement and grading of cranial asymmetry in children with and without torticollis. Clin Orthod Res. 2001;4:200-205.

35 Frühwald J, Schicho KA, Figl M, et al. Accuracy of craniofacial measurements: computed tomography and three-dimensional computed tomography compared with stereolithographic models. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:22-26.

36 Hutchison BL, Hutchison LA, Thompson JM, Mitchell EA. Quantification of plagiocephaly and brachycephaly in infants using a digital photographic technique. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2005;42:539-547.

37 Littlefield TR, Kelly KM, Cherney JC, et al. Development of a new three-dimensional cranial imaging system. J Craniofac Surg. 2004;15:175-181.

38 Netherway DJ, Abbott AH, Gulamhuseinwala N, et al. Three-dimensional computed tomography cephalometry of plagiocephaly: asymmetry and shape analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2006;43:201-210.

39 Plank LH, Giavedoni B, Lombardo JR, et al. Comparison of infant head shape changes in deformational plagiocephaly following treatment with a cranial remolding orthosis using a noninvasive laser shape digitizer. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17:1084-1091.

40 van Vlimmeren LA, Takken T, van Adrichem LN, et al. Plagiocephalometry: a non-invasive method to quantify asymmetry of the skull. A reliability study. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165:149-157.

41 Zonenshayn M, Kronberg E, Souweidane MM. Cranial index of symmetry: an objective semiautomated measure of plagiocephaly. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(suppl):537-540.

42 Mortenson PA, Steinbok P. Quantifying positional plagiocephaly: reliability and validity of anthropometric measurements. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17:413-419.

43 Graham JMJr, Kreutzman J, Earl D, et al. Deformational brachycephaly in supine-sleeping infants. J Pediatr. 2005;146:253-257.

44 Hellbusch JL, Hellbusch LC, Bruneteau RJ. Active counter-positioning treatment of deformational occipital plagiocephaly. Nebr Med J. 1995;80:344-349.

45 Moss SD. Nonsurgical, nonorthotic treatment of occipital plagiocephaly: what is the natural history of the misshapen neonatal head? J Neurosurg. 1997;87:667-670.

46 Malloy MH. Positioning and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): update. Pediatrics. 1996;98:1216-1218.

47 Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. The changing concept of sudden infant death syndrome: diagnostic coding shifts, controversies regarding the sleeping environment, and new variables to consider in reducing risk. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1245-1255.

48 Boere-Boonekamp MM, van der Linden-Kuiper LL. Positional preference: prevalence in infants and follow-up after two years. Pediatrics. 2001;107:339-343.

49 Losee JE, Mason AC, Dudas J, et al. Nonsynostotic occipital plagiocephaly: factors impacting onset, treatment, and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:1866-1873.

50 McGarry A, Dixon MT, Greig RJ, et al. Head shape measurement standards and cranial orthoses in the treatment of infants with deformational plagiocephaly: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:568-576.

51 Rogers GF, Miller J, Mulliken JB. Comparison of a modifiable cranial cup versus repositioning and cervical stretching for the early correction of deformational posterior plagiocephaly. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:941-947.

52 Loveday BP, de Chalain TB. Active counterpositioning or orthotic device to treat positional plagiocephaly? J Craniofac Surg. 2001;12:308-313.

53 NHS Quality Improvement. The use of cranial orthosis treatment for infant deformational plagiocephaly. Evidence Note No. 16, April 2007. Retrieved May 1, 2008, from http://www.nhshealthquality.org/nhsqis/files/Infant%20plagiocephaly%20final%20May%202007.pdf

54 Bialocerkowski AE, Vladusic SL, Howell SM. Conservative interventions for positional plagiocephaly: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:563-570.

55 Persing J, James H, Swanson J, et al. Prevention and management of positional skull deformities in infants. American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Report. Pediatrics. 2003;112:199-202.