CHAPTER 238 Piriformis Syndrome, Obturator Internus Syndrome, Pudendal Nerve Entrapment, and Other Pelvic Entrapments

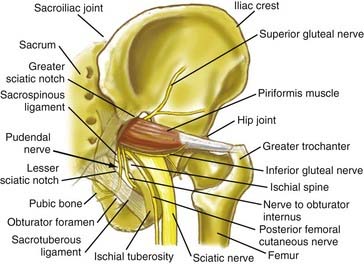

Pain in the upper buttock over the posterior superior iliac spine may also be due to entrapment of the superior cluneal nerves. Nonradiating pain in the mid buttock may be direct pain from the piriformis muscle or may be related to a trochanteric bursitis. Pain involving the piriformis muscle often includes associated radiating nerve pain such as sciatica because the sciatic nerve passes through the sciatic notch along with the piriformis muscle (Fig. 238-1).

Diagnosis and Management of Pelvic Sciatic Syndromes

Physical Examination Findings in Pelvic Sciatic Entrapment Syndromes

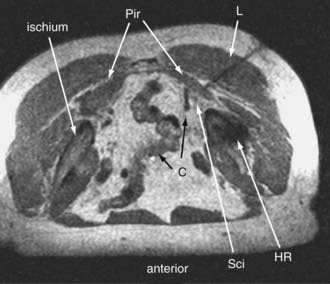

Sciatic entrapments at the sciatic notch often affect all five toes (multiple dermatomes) rather than just the lateral toes (S1 radiculopathy) or medial toes (L5 radiculopathy), which is most commonly seen in those with herniated lumbar disks. The pain of sciatic entrapment more commonly extends primarily only as far as the knee, ankle, or heel—not reaching the toes at all. Straight leg raising is generally negative, but resisted abduction or adduction of the flexed internally rotated thigh usually reproduces the symptoms. Sciatic notch tenderness is present in all patients with piriformis syndromes (Fig. 238-2), so other variant types of pelvic sciatic entrapment should be considered when this examination feature is not present. Trochanteric bursitis responsive to injection of the bursa occurred in 7% of patients diagnosed with muscle-based piriformis syndrome.

Neurography Results for Sciatica of Nondisk Origin

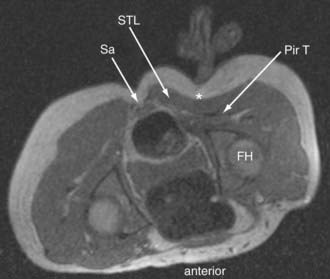

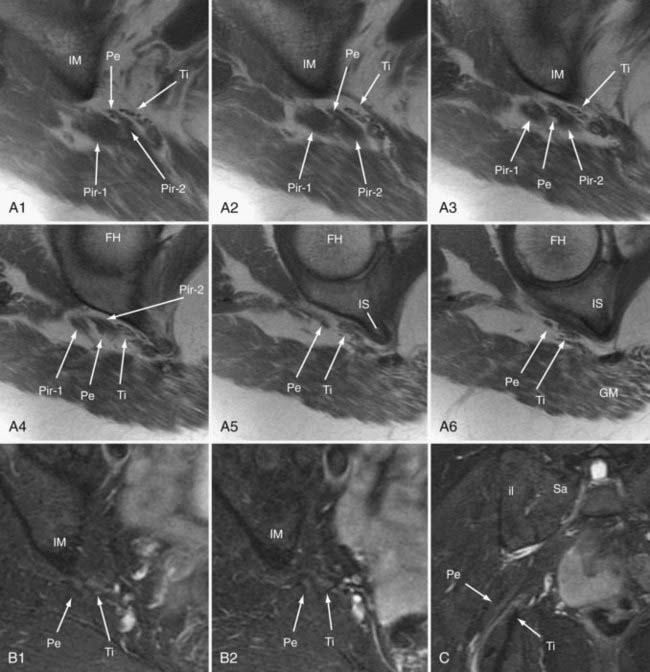

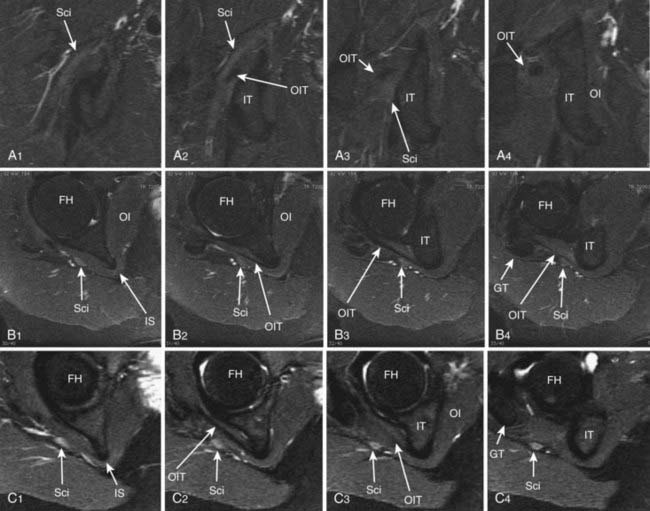

Until recently, objective tests for the existence of piriformis syndrome were very limited, there was no reliable effective treatment, and the pathophysiology was not well understood.1 Piriformis syndrome remains a subject of significant debate within the neurosurgical community.2,3 However, magnetic resonance neurography has proved helpful in providing objective diagnostic criteria.4 Figure 238-3 demonstrates the appearance of the sciatic nerve in a magnetic resonance neurography image in a typical pelvic sciatic entrapment case. Ipsilateral piriformis muscle hypertrophy is a common image finding in piriformis syndrome.5,6 Ipsilateral muscle atrophy occurs in some patients as well. Edema or hyperintensity in the ipsilateral sciatic nerve relative to the contralateral nerve occurs in 88%.4

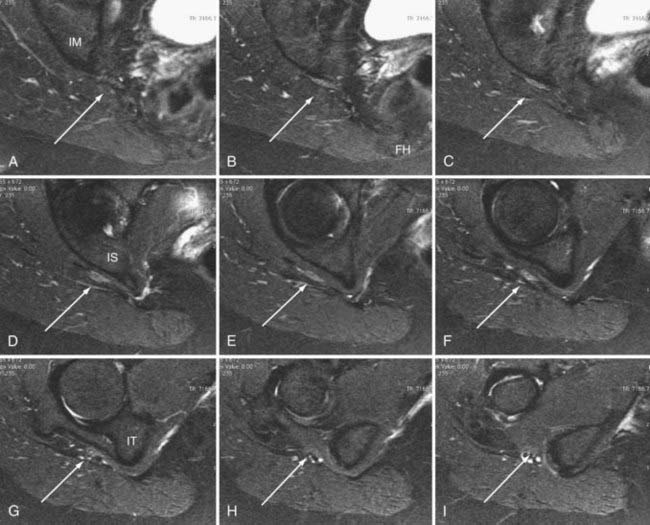

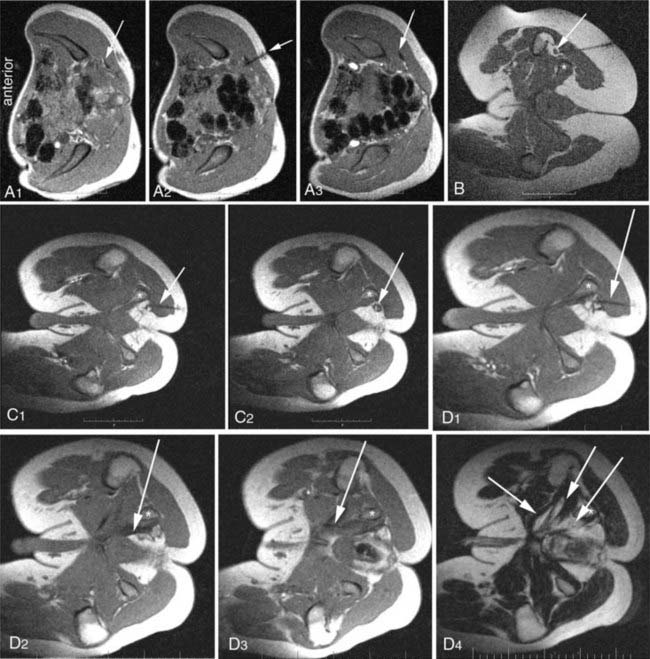

In addition to entrapment at the sciatic notch, the sciatic nerve may be compressed by fibrous bands and by dilated venous varices when the dilated vein arises inside the perineurial sheath. It may suffer entrapment owing to fixation by an artery passing through the nerve and by tendon or muscle passing through the nerve (Fig. 238-4). In some individuals, the sciatic nerve does not contact the tendon of the obturator internus, but in others, it may be entrapped by that tendon (Fig. 238-5). Entrapment also occurs in the lower ischial tunnel adjacent to the hamstring attachments or at the quadratus femoris muscle.

Open Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Guided Injections for Piriformis Syndrome

Because of the large volume of bupivacaine, procedures should be carried out in a surgicenter setting. The injection is monitored with fast (10 to 15 seconds) three-slice image sets—a working image and the two adjacent images slices. The needle advance must be maintained in the center slice of the three-slice set so that an accurate depiction of needle depth is seen. Because the piriformis muscle is often no more than 1 to 2 cm thick (Fig. 238-6), and because the bowel is often adjacent just deep to the muscle, it is necessary to reimage once or twice with each movement of the needle. Lower-accuracy alternatives to open MRI include x-ray fluoroscopy with the needle directed toward the space below the sacroiliac joint, computed tomography (CT) guidance, or electromyography with ultrasound.7

Minimal Access Surgery for Pelvic Entrapments of the Sciatic Nerve

Surgery is carried out generally on an outpatient basis using a 3-cm incision for a minimally invasive transgluteal approach with piriformis muscle resection, neuroplasty of the sciatic nerve and of the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve,8 and then placement of Seprafilm (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) as an adhesiolytic agent. A similar approach is used for sciatic entrapments at the level of the ischial tuberosity.

Diagnosis and Management of Pudendal Syndromes

Entrapments of the Pudendal Nerve and the Nerve to the Obturator Internus

Recognition and treatment of pudendal nerve entrapment (PNE) syndrome has an extended history,9,10 and the first large-scale study was published in 1998.11 There are now numerous general publications covering various aspects of diagnosis and treatment.12–17 However, the success rate in treating pudendal neuralgias has not been satisfactory18–20 until recently.21 One problem in the past was a lack of appreciation that there are several subtypes with different anatomic bases and presentations.22–27 Further, the surgical anatomy of the pudendal nerve is subject to significant individual variation.28

Targeting of pudendal nerve injections by electrodiagnostic technique,29 C-arm fluoroscopy,30,31 and CT scan has been described.32–34 Diagnosis has also relied on pudendal nerve latency testing,35,36 but diagnostic imaging has really played very little role in the past. A recent large scale study on treatment of this condition, using magnetic resonance neurography,37–39 open MRI–guided injections4 (Fig. 238-7), and new minimal access surgical techniques has provide significant clarification.21

Pudendal nerve entrapment can be categorized into four major categories based on the location of the entrapment.21 These include type I—exclusively at the level of the piriformis muscle in the sciatic notch only (3.5%), type II—at the level of the ischial spine and sacrotuberous ligament (9%), type III—in Alcock’s canal on the medial surface of the obturator internus 78.5%, and type IV—at distal branches (9%).21

Presentation of Pudendal Syndromes

The symptoms of PNE involve pain, dysfunction, and numbness in all or part of the distribution of the nerve. This includes the saddle area between the legs, including genitalia, rectum, and terminal urinary tract, as well as pelvic floor musculature. In addition, sexual dysfunction and sphincter dysfunction are often seen. Sexual dysfunctions included female continuous arousal as well as lack of sensation, male impotence, and dyspareunia. Aggravation by sitting is common when the obturator internus or piriformis muscles are involved, but there is not always a positional trigger. Most cases are unilateral, even though some patients have difficulty identifying laterality of pain in midline urogenital structures, but bilateral pudendal entrapment occurs in more than 25% of cases. Patients reported in the 2008 study21 ranged in age from 8 to 82 years, and there was no significant male or female preponderance.

Physical Examination Findings in Pudendal Syndromes

The most common finding is sensitivity to palpation at the obturator internus muscle elicited by manual compression on the deep medial aspect of the ischial tuberosity. Reproduction of symptoms with straight leg raising is rare; however, adduction of the thigh in a seated position, passive internal or external rotation of the hip joint, and resisted abduction or adduction of the flexed internally rotated thigh4 also elicited symptoms in some individuals.

Open Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Guided Injections for Pudendal Syndromes

In patients obtaining no alteration of symptoms from dense proximal pudendal nerve block, open MRI can be used to guide injection through a lateral subcoccygeal approach to block the ganglion impar to rule out autonomically driven, nonpudendal saddle area pain syndromes. This approach is similar to paramedian approaches40 as opposed to transcoccygeal approaches.41,42

Pudendal Entrapment Surgical Management

Surgery can be done using minimal access approaches on an outpatient or overnight-stay basis. The surgical approach for patients with piriformis muscle involvement is similar to what is described earlier for piriformis surgery.4 Following that approach and any resection of the piriformis muscle, a retrosciatic dissection is commenced. Using an approach over the posterior and inferior surface of the sciatic nerve, and relying on intraoperative stimulation, the nerve to the obturator internus is identified and then tracked proximally into the greater sciatic notch, where it runs deep to the sciatic nerve where progressive release of any adhesions is carried out. The pudendal nerve is then identified through direct nerve stimulation in its typical position adjacent and posterior to the nerve to the obturator internus inside the greater sciatic notch. Neuroplasty of the pudendal nerve from this point and continuing inferiorly across the ischial spine and into the lesser sciatic notch is then carried out. From this access, it is generally possible to dilate Alcock’s canal to a depth of 2 to 3 cm along its course using gentle application of a long tonsil clamp. Care is taken not to disrupt the veins and arteries in the retrosciatic space, but any bleeding should be managed initially with gentle pressure and placement of thrombin-soaked Gelfoam to avoid excessive coagulation near the numerous nerve elements.

In patients with distal branch entrapments (e.g., isolated penile numbness), the incision is centered between the ischial spine and the ischial tuberosity; this approach takes the surgeon directly to the sacrotuberous ligament. After the ligament is exposed, the pudendal nerve can be accessed distally along the course of Alcock’s canal as well as along its proximal approach to the lesser sciatic notch. In patients who have a dense adhesion of the pudendal nerve to the deep surface of the sacrotuberous ligament, it is possible to carry out partial or complete section of the ligament to access the nerve, as some have advocated,20 but most entrapments can be released without sectioning this major structural ligament. Hruby and colleages26 also described direct anterior approaches for decompression of small distal sensory branches of the pudendal nerve.

Anterior Pelvis: Ilioinguinal, Femoral, Obturator, and Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerves

Injury to ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, and iliohypogastric nerves is usually by direct compression, stretch, laceration, suture, or entrapment by scar following abdominal or pelvic surgeries.43–50 Ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, and iliohypogastric nerves are most commonly injured during herniorrhaphies, followed by appendectomies and hysterectomies.45–4749

Patients with ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, and iliohypogastric neuralgias present with chronic groin pain, dysesthesias, or sensory loss. Symptoms may involve the medial thigh as well. The classic diagnostic triad is (1) burning pain in the region of the incision or along the nerve course, radiating into the groin and medial thigh; (2) decreased sensation in the distribution of the nerve; and (3) pain relief following nerve block. Electromyogram may reveal denervation of the pyramidalis muscle, which is specific for ilioinguinal nerve injury. Patients with groin neuralgia should undergo gynecologic or urologic evaluation as appropriate; the differential diagnosis includes tumor, intermittent torsion, hydrocele, varicocele, and inguinal hernia. If the pain recurs after conservative management and local nerve block, resection or neuroplasty of the involved nerves is about 90% successful. The original abdominal incision is opened and extended toward the anterior superior iliac spine, along the course of involved nerve or nerves. The aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle is split in the direction of the muscle fibers, and the nerve is localized by elevating the fascia from the internal oblique muscle. The nerve is then followed medially to the site of entrapment, subject to neuroplasty, or widely resected. A retroperitoneal approach may also be used in the event of extensive scar formation or mesh use in the groin. Postoperative side effects following either approach may include numbness in the distribution of the nerve and loss of the cremasteric reflex.49 Formation of a painful neuroma is always a risk when resection is chosen over neuroplasty.

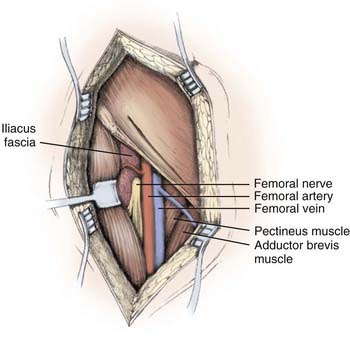

The femoral nerve lies between the iliacus and psoas muscles in the retroperitoneal space. Femoral nerve entrapment at the pelvic level typically results in iliopsoas and quadriceps weakness as well as anterior thigh pain. Penetrating trauma to the abdomen or iatrogenic misadventures may lead to proximal femoral nerve entrapment. Patients with hemophilia or those receiving anticoagulation may develop intramuscular (iliopsoas) clots resulting in femoral nerve injury.51

On examination, iliopsoas weakness is demonstrated by asking the patient to flex the hip. This can be accentuated by flexing the hip against resistance when lying flat. Quadriceps weakness is shown by asking the patient to extend the knee. Surgical exposure of the pelvic portion of the femoral nerve involves a combined retroperitoneal and thigh-level approach, with a vertical anterior incision extending from the inguinal ligament into the femoral triangle (Fig. 238-8).

(From Kline DG, Hudson KR, Kim DH: Atlas of Peripheral Nerve Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001.)

The obturator nerve exits the obturator foramen and then passes below the inguinal ligament just medial to the femoral vessels. Entrapments of the obturator nerve can be released through a small incision parallel to and just distal to the inguinal ligament, using palpation of the femoral artery and identification of the femoral vein to ensure that they are well distinguished from the femoral nerve branches that emerge from beneath the inguinal ligament lateral to the vessels. Access is available from the distal to the inguinal ligament up to the obturator foramen. Injections to relax the obturator internus muscle21 can help distinguish entrapments proximal to the foramen.

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) travels obliquely over the psoas muscle, then lateral to femoral nerve and medial to the anterior superior iliac spine. The LFCN supplies sensation to the skin of the lateral thigh. Meralgia paresthetica, or entrapment of the LFCN, may be idiopathic or may follow iatrogenic injury. The classic presenting symptoms are numbness, hyperesthesia, and paresthesias in a “pants pocket” distribution, over the anterolateral thigh. Treatment involves neuroplasty with or without resection of the LFCN as it courses medial to the anterior superior iliac spine just below the inguinal ligament, and results in amelioration of symptoms in more than 70% of operations.43,52 Because the LFCN typically divides into at least two branches distal to the inguinal ligament, care must be taken to resect or decompress all the branches to avoid persistent symptoms.

Amarenco G, Kerdraon J. Pudendal nerve terminal sensitive latency: technique and normal values. J Urol. 1999;161:103.

Bascom JU. Pudendal canal syndrome and proctalgia fugax: a mechanism creating pain. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:406.

Benson JT, Griffis K. Pudendal neuralgia, a severe pain syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1663.

Cardosi RJ, Cox CS, Hoffman MS. Postoperative neuropathies after major pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:240.

Choi PD, Nath R, Mackinnon SE. Iatrogenic injury to the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves in the groin: a case report, diagnosis, and management. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;37:60.

Choi SS, Lee PB, Kim YC, et al. C-arm-guided pudendal nerve block: a new technique. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:553.

Filler AG. Diagnosis and management of pudendal nerve entrapment syndromes: impact of MR neurography and open MR-guided injections. Neurosurg Q. 2008;18:1.

Filler AG. Piriformis and related entrapment syndromes: diagnosis and management. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2008;19:609-622.

Filler AG, Haynes J, Jordan SE, et al. Sciatica of nondisc origin and piriformis syndrome: diagnosis by magnetic resonance neurography and interventional magnetic resonance imaging with outcome study of resulting treatment. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:99.

Goldner J, Hall R. Nerve entrapment syndromes of the low back and lower extremities. In Omer G, Spinner M, Van Beek A, editors: Management of Peripheral Nerve Problems, 2nd ed, Philadelphia: Saunders, 1998.

Hruby S, Ebmer J, Dellon AL, et al. Anatomy of pudendal nerve at urogenital diaphragm: new critical site for nerve entrapment. Urology. 2005;66:949.

Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, et al. Intrapelvic and thigh-level femoral nerve lesions: management and outcomes in 119 surgically treated cases. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:989.

Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, et al. Surgical management of 33 ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuralgias at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1013.

Kline DG, Hudson AR, Kim DH. Atlas of Peripheral Nerve Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001.

Labat JJ, Riant T, Robert R, et al. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:820-827.

Loukas M, Louis RGJr, Hallner B, et al. Anatomical and surgical considerations of the sacrotuberous ligament and its relevance in pudendal nerve entrapment syndrome. Surg Radiol Anat. 2006;28:163.

Mahakkanukrauh P, Surin P, Vaidhayakarn P. Anatomical study of the pudendal nerve adjacent to the sacrospinous ligament. Clin Anat. 2005;18:200.

Nahabedian MY, Dellon AL. Outcome of the operative management of nerve injuries in the ilioinguinal region. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:265.

Peng PW, Tumber PS. Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures for patients with chronic pelvic pain: a description of techniques and review of literature. Pain Physician. 2008;11:215.

Popeney C, Ansell V, Renney K. Pudendal entrapment as an etiology of chronic perineal pain: diagnosis and treatment. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:820.

Ramsden CE, McDaniel MC, Harmon RL, et al. Pudendal nerve entrapment as source of intractable perineal pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82:479.

Siu TL, Chandran KN. Neurolysis for meralgia paresthetica: an operative series of 45 cases. Surg Neurol. 2005;63:19.

Thoumas D, Leroi AM, Mauillon J, et al. Pudendal neuralgia: CT-guided pudendal nerve block technique. Abdom Imaging. 1999;24:309.

Tiel RL. Piriformis and related entrapment syndromes: myth and fallacy. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2008;19:623-627.

Whiteside JL, Barber MD, Walters MD, et al. Anatomy of ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves in relation to trocar placement and low transverse incisions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1574.

1 Spinner RJ, Thomas NM, Kline DG. Failure of surgical decompression for a presumed case of piriformis syndrome: case report. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:652.

2 Filler AG. Piriformis and related entrapment syndromes: diagnosis and management. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2008;19:609-622.

3 Tiel RL. Piriformis and related entrapment syndromes: myth and fallacy. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2008;19:623-627.

4 Filler AG, Haynes J, Jordan SE, et al. Sciatica of nondisc origin and piriformis syndrome: diagnosis by magnetic resonance neurography and interventional magnetic resonance imaging with outcome study of resulting treatment. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:99.

5 Jankiewicz JJ, Hennrikus WL, Houkom JA. The appearance of the piriformis muscle syndrome in computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;262:205-209.

6 Rossi P, Cardinali P, Serrao M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in piriformis syndrome: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:519.

7 Peng PW, Tumber PS. Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures for patients with chronic pelvic pain: a description of techniques and review of literature. Pain Physician. 2008;11:215.

8 Vandertop WP, Bosma NJ. The piriformis syndrome: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:1095.

9 Darget R. [Treatment of pelvic pain by the enervation by gluteal route of the pudendal nerve.]. J Urol Med Chir. 1955;61:98.

10 Turner ML, Marinoff SC. Pudendal neuralgia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:1233.

11 Robert R, Prat-Pradal D, Labat JJ, et al. Anatomic basis of chronic perineal pain: role of the pudendal nerve. Surg Radiol Anat. 1998;20:93.

12 Pisani R, Stubinski R, Datti R. Entrapment neuropathy of the internal pudendal nerve: report of two cases. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1997;31:407.

13 Antolak SJJr, Hough DM, Pawlina W, et al. Anatomical basis of chronic pelvic pain syndrome: the ischial spine and pudendal nerve entrapment. Med Hypotheses. 2002;59:349.

14 Ramsden CE, McDaniel MC, Harmon RL, et al. Pudendal nerve entrapment as source of intractable perineal pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82:479.

15 Benson JT, Griffis K. Pudendal neuralgia, a severe pain syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1663.

16 Popeney C, Ansell V, Renney K. Pudendal entrapment as an etiology of chronic perineal pain: diagnosis and treatment. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:820.

17 Labat JJ, Riant T, Robert R, et al. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:820-827.

18 Mauillon J, Thoumas D, Leroi AM, et al. Results of pudendal nerve neurolysis: transposition in twelve patients suffering from pudendal neuralgia. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:186.

19 Beco J, Climov D, Bex M. Pudendal nerve decompression in perineology: a case series. BMC Surg. 2004;4:15.

20 Robert R, Labat JJ, Bensignor M, et al. Decompression and transposition of the pudendal nerve in pudendal neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial and long-term evaluation. Eur Urol. 2005;47:403.

21 Filler AG. Diagnosis and management of pudendal nerve entrapment syndromes: impact of MR Neurography and open MR-guided injections. Neurosurg Q. 2008;18:1.

22 Shafik A. Pudendal canal decompression in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Arch Androl. 1994;32:141.

23 Oberpenning F, Roth S, Leusmann DB, et al. The Alcock syndrome: temporary penile insensitivity due to compression of the pudendal nerve within the Alcock canal. J Urol. 1994;151:423.

24 Bascom JU. Pudendal canal syndrome and proctalgia fugax: a mechanism creating pain. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:406.

25 Shafik A. Pudendal canal syndrome: a cause of chronic pelvic pain. Urology. 2002;60:199.

26 Hruby S, Ebmer J, Dellon AL, et al. Anatomy of pudendal nerve at urogenital diaphragm: new critical site for nerve entrapment. Urology. 2005;66:949.

27 Loukas M, Louis RGJr, Hallner B, et al. Anatomical and surgical considerations of the sacrotuberous ligament and its relevance in pudendal nerve entrapment syndrome. Surg Radiol Anat. 2006;28:163.

28 Mahakkanukrauh P, Surin P, Vaidhayakarn P. Anatomical study of the pudendal nerve adjacent to the sacrospinous ligament. Clin Anat. 2005;18:200.

29 Naja MZ, Al-Tannir MA, Maaliki H, et al. Nerve-stimulator-guided repeated pudendal nerve block for treatment of pudendal neuralgia. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2006;23:442.

30 Abdi S, Shenouda P, Patel N, et al. A novel technique for pudendal nerve block. Pain Physician. 2004;7:319.

31 Choi SS, Lee PB, Kim YC, et al. C-arm-guided pudendal nerve block: a new technique. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:553.

32 Thoumas D, Leroi AM, Mauillon J, et al. Pudendal neuralgia: CT-guided pudendal nerve block technique. Abdom Imaging. 1999;24:309.

33 Calvillo O, Skaribas IM, Rockett C. Computed tomography-guided pudendal nerve block: a new diagnostic approach to long-term anoperineal pain: a report of two cases. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2000;25:420.

34 Hough DM, Wittenberg KH, Pawlina W, et al. Chronic perineal pain caused by pudendal nerve entrapment: anatomy and CT-guided perineural injection technique. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:561.

35 Amarenco G, Kerdraon J. Pudendal nerve terminal sensitive latency: technique and normal values. J Urol. 1999;161:103.

36 Robert R, Labat JJ, Riant T, et al. Neurosurgical treatment of perineal neuralgias. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 2007;32:41.

37 Filler AG, Kliot M, Howe FA, et al. Application of magnetic resonance neurography in the evaluation of patients with peripheral nerve pathology. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:299.

38 Filler AG, Maravilla KR, Tsuruda JS. MR neurography and muscle MR imaging for image diagnosis of disorders affecting the peripheral nerves and musculature. Neurol Clin. 2004;22:643.

39 Filler AG, Howe FA, Hayes CE, et al. Magnetic resonance neurography. Lancet. 1993;341:659.

40 McAllister RK, Carpentier BW, Malkuch G. Sacral postherpetic neuralgia and successful treatment using a paramedial approach to the ganglion impar. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:1472.

41 Munir MA, Zhang J, Ahmad M. A modified needle-inside-needle technique for the ganglion impar block. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:915.

42 Toshniwal GR, Dureja GP, Prashanth SM. Transsacrococcygeal approach to ganglion impar block for management of chronic perineal pain: a prospective observational study. Pain Physician. 2007;10:661.

43 Kline DG, Hudson AR. Nerve Injuries: Operative Results for Major Nerve Injuries, Entrapments, and Tumors, 1st ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995.

44 Goldner J, Hall R. Nerve entrapment syndromes of the low back and lower extremities. In Omer G, Spinner M, Van Beek A, editors: Management of Peripheral Nerve Problems, 2nd ed, Philadelphia: Saunders, 1998.

45 Whiteside JL, Barber MD, Walters MD, et al. Anatomy of ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves in relation to trocar placement and low transverse incisions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1574.

46 Nahabedian MY, Dellon AL. Outcome of the operative management of nerve injuries in the ilioinguinal region. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:265.

47 Cardosi RJ, Cox CS, Hoffman MS. Postoperative neuropathies after major pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:240.

48 El-Minawi AM, Howard FM. Iliohypogastric nerve entrapment following gynecologic operative laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:871.

49 Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, et al. Surgical management of 33 ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuralgias at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1013.

50 Choi PD, Nath R, Mackinnon SE. Iatrogenic injury to the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves in the groin: a case report, diagnosis, and management. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;37:60.

51 Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, et al. Intrapelvic and thigh-level femoral nerve lesions: management and outcomes in 119 surgically treated cases. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:989.

52 Siu TL, Chandran KN. Neurolysis for meralgia paresthetica: an operative series of 45 cases. Surg Neurol. 2005;63:19.