Physical and Chemical Restraint

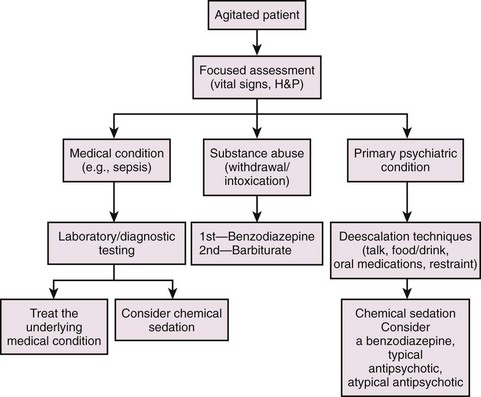

Emergency clinicians often face the challenge of caring for agitated, uncooperative, combative, and violent patients who are unable to participate in their care or make rational health care decisions or are a danger not only to themselves but to medical personnel as well.1,2 Psychiatric illness, acute chemical intoxication or withdrawal, various stages of delirium, medical illness, uncontrolled rage, hypoxia, and rarely, central nervous system infection are causes of agitated or violent behavior in the emergency department (ED).1 Excited delirium syndrome (EXDS), a variant of and the extreme form of agitated delirium, is a recently defined syndrome (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21440403).3 EXDS is at the far end of the spectrum of agitation. It appears to be a specific entity with unique characteristics. EXDS can be fatal, often as a result of severe physiologic and metabolic derangements from the combination of underlying agitation and continued violent exertion, coupled with physical restraint.3 Causes of agitated delirium include manic-depressive disorder, psychosis, chronic schizophrenia, intoxication with sympathomimetics or anticholinergics, cocaine intoxication, alcohol withdrawal, hypoglycemia, the postictal state, or head trauma. Some causes are idiopathic, but many are due to a combination of underlying psychiatric illness and stimulant drugs or alcohol (or both). Because of the variety of causes, management of agitated and combative patients requires a systematic approach (Fig. 70-1).

Any medical condition that leads to brain dysfunction may also result in agitated, combative, or violent behavior (Box 70-1). Well-documented examples include hypoglycemia, hypoxia, medication intoxication, encephalitis, meningitis, intracranial hemorrhage, thyrotoxicosis, traumatic brain injury, febrile illnesses in the elderly, and dementia.4

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, reports of restraint-associated deaths in psychiatric and extended care facilities5 led lawmakers to pass legislation establishing regulations for the use of restraint.6 Since then, the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have created standards governing the use of restraint in a variety of health care settings, including EDs and tertiary care facilities (Box 70-2).7,8 The aforementioned standards allow the use of physical restraint for a limited period. A licensed practitioner must evaluate the patient and determine that less restrictive interventions have been ineffective and physical restraint is required to ensure the patient’s well-being. The standards also include requirements for written policies and procedures governing the use of restraint that must address indications, staff training and education, patient assessment and reevaluation, appropriate documentation, and patient-focused issues such as maintaining dignity and respect. Hospitals and extended care facilities are required by law to report any death or adverse event related to the use of restraint.8

Some authors have advocated “restraint-free” environments in nursing homes, extended care facilities, and acute care hospitals.9 Although this concept is laudable, mandating a restraint-free ED is impractical and potentially dangerous. Clinicians should recognize the risks associated with restraining a patient; however, they should not be deterred from using either physical or chemical restraint when patients demonstrate dangerous behavior toward themselves or others. Indeed, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) recently reaffirmed their policy statement in 2007 by supporting the careful and appropriate use of physical and chemical restraint or seclusion.10

Medicolegal Concerns

Emergency clinicians need to be cognizant of the potential legal ramifications stemming from physically restraining patients. The risk for litigation may be mitigated by strict adherence to written institutional and departmental policies regarding the use of restraint and medications. Unfortunately, no one-size-fits-all protocol is realistic, and each case must be individualized by a clinician at the bedside, often with little data or background on which to base a specific intervention. Emphasis should be placed on timely and comprehensive assessment before restraint, regular patient reevaluation, limitations on the time spent in restraint, and detailed documentation in the ED record. Furthermore, clinicians need to recognize that competent patients do have the legal right to refuse medical treatment even if the result of their refusal is death or serious bodily harm. Competence, however, may be difficult to evaluate or ascertain in the time frame required to make important clinical decisions. There are many gray areas that cannot simply be solved by attempting to obtain a formal psychiatric consultation. In fact, there are no data proving that a psychiatrist is any better than an emergency physician in determining competence in an ED patient within the time frame of the ED evaluation, when important decisions must be made. Individuals with true EXDS are clearly mentally incompetent, but coercive measures, including physical restraint or the threat of physical restraint, should not be used simply because a competent patient refuses treatment or as retaliation for perceived disruptive behavior.11

Patient Assessment

Emergency clinicians must avoid ascribing agitated or abusive behavior to drug or alcohol intoxication or underlying psychiatric disease before considering severe, life-threatening diagnoses (see Box 70-1). Every attempt should be made to obtain a detailed history of issues related to the patient’s condition, as well as the patient’s past medical and psychiatric history, including medications, drug and alcohol use, and previous similar events. In reality, such information is rarely available or accurate, thus leaving only the clinician’s clinical judgment to guide therapy.

Five groups of patients have been identified as being at increased risk for an underlying medical problem: the elderly, those with a history of substance abuse, patients without a previous psychiatric disorder, those with preexisting or new medical complaints, and individuals from lower socioeconomic groups.12,13 Of these, patients with new psychiatric symptoms are especially worrisome and require careful evaluation for underlying medical illness.14

Once a patient has been restrained, frequent periodic reevaluation is paramount to the patient’s safety and is required by the JCAHO (see Box 70-2).15 Reevaluation of restrained patients should include a reassessment of vital signs, neurologic status, respiratory status, skin condition, and perfusion of the extremities (Box 70-3). Physical restraints should be removed as soon as the clinician has determined that patients are no longer a risk to themselves or others.

Deescalation Techniques

Coburn and Mycyk described three phases of escalating violence: anxiety, defensiveness, and finally, physical aggression.16 Recognition of this somewhat predictable pattern may help in defusing a difficult situation before physical or chemical restraint is necessary. Indeed, several deescalation techniques have been shown to assist in quelling agitated and violent patients.2

One simple, yet effective technique is verbally engaging the patient by asking, “how can we help you?” This display of compassion on the part of the treating clinician and staff may calm the patient. Similarly, offering food and drink will often soothe an agitated patient. Along with these displays of caring and empathy, it is important to impress on the patient that violent behavior will not be tolerated and will be dealt with quickly and firmly.2 If the patient continues to demonstrate agitated or violent behavior, enlist the aid of a family member or a specially trained individual, such as a social worker, psychiatric counselor, or member of the clergy.

Types of Patient Restraint

The utility of seclusion in psychiatric evaluation units and inpatient hospital wards is well documented in both adult and pediatric populations.17–20 In the mid-1980s, seclusion was commonly used to calm combative and violent ED patients, but its popularity has declined since then.1,21,22 Reasons for this decline are unclear but probably include lack of adequate space and concerns regarding provision of medical care and compliance with regulatory agencies.22 Nevertheless, at institutions with adequate physical space and well-designed policies and procedures, experience has shown that seclusion is an effective ED practice for selected patients.22,23

Seclusion involves placing agitated and violent patients in an isolated space and confining them to dedicated hospital stretchers or beds that are secured in place to prevent injury. Seclusion is often used in conjunction with chemical sedation, physical restraint, or both.22 The seclusion room should be located near ED staff to allow continuous patient observation. Regularly reassess patients who are placed in seclusion, similar to physically restrained patients (see Box 70-3).

Physical Restraint

Research regarding the application of physical restraint in the ED is limited. In one prospective study of restraint-associated complications in 298 ED patients, minor complications occurred in only 7% of patients, and there were no serious complications or deaths.24 The author of this study concluded that the dangers of ED patient restraint promulgated by professional organizations and health care regulators may be overstated.24 Moreover, this study supports the safe use of restraint by emergency clinicians, who by virtue of their training and experience are experts in recognizing signs of deterioration and skilled in airway management and resuscitation. It should also be noted that JCAHO sentinel event tracking has demonstrated a decreased rate of complications when patients are restrained on their sides.16,25

Although the actual prevalence of patient restraint in EDs is unknown, it has been estimated that 25% of teaching hospitals physically restrain at least one person per day.1

Restraint Devices

Limb Holders (Restraints): Restraining a patient’s extremities is the primary method of physical restraint used in the ED. Limb restraints are constructed from a variety of materials, including leather, synthetic leather, cotton, and single-use foam material. These materials provide restraint that differs in strength, ease of removal, and cleaning.

Hard leather and synthetic leather limb holders are virtually impossible to break or tear but are difficult to sterilize if they become soiled with blood or body fluids (Fig. 70-2). They are more rigid than soft restraints, which also makes them somewhat more difficult and time-consuming to apply. More importantly, most leather limb holders require a key to unlock and, as a result, might take longer to remove after an adverse event such as vomiting or respiratory arrest. Leather limb holders are generally used to restrain combative and violent patients in whom the need for indestructible secure restraints outweighs the more time-consuming application and removal process.

Soft limb restraints are usually made from cotton or foam material, or both (Fig. 70-3). They are single-use devices, which obviates the need for cleaning and sterilization. Soft limb restraints are less rigid than leather limb restraints, which makes them easier to apply. In addition, because they are fastened without the use of a key, soft limb restraints are more easily removed. Soft restraints are typically used for agitated but less combative patients because they are not as secure as leather limb holders.

Belts/Fifth-Point Restraint: A fifth-point restraint is a belt apparatus used to supplement the use of four limb restraints by holding down the thighs, chest, or pelvis (Fig. 70-4). A fifth-point restraint is used on patients who continue to be at risk for harming themselves despite adequate limb restraint and whose continued combative behavior interferes with diagnostic or therapeutic interventions. When patients are restrained across the thighs, chest, or pelvis, they may not be able to sit up or turn onto their sides, thus placing them at higher risk for aspiration should vomiting occur. Keep the side rails of the stretcher in the upright position at all times and place the belt snugly enough to prevent the patient from slipping under the device and thereby increasing the risk for accidental suffocation. Fifth-point restraints are usually made of synthetic material and are available with both quick-release and key-release locks.

Jackets and Vests: Jackets and vests are generally used on inpatient wards and extended care facilities for the prevention of falls; they have little utility in the ED (Fig. 70-5). Moreover, these products have been implicated in a number of restraint-associated deaths secondary to choking and suffocation. The use of restraint jackets and vests in the ED is not recommended.

Hobble Leg Restraints: Hobble leg restraints limit movement by securing the patient’s ankles with connecting locking cuffs (Fig. 70-6). Hobble leg restraints are commonly used by law enforcement agencies because they impede running and kicking, which makes them an effective method of transporting potentially violent patients and those who pose a risk for flight. Hobble leg restraints are seldom used in the ED, but their use by law enforcement agencies and prison authorities means that most emergency clinicians will encounter patients placed in these devices. The combination of prone positioning, hobble leg restraints, and binding a patient’s hands behind the back, commonly referred to as hog-tying, was a common method of restraining prisoners and violent psychiatric patients (Fig. 70-7). However, this practice is no longer widely used because of the risk for suffocation (see “Positional Asphyxia,” later).

Indications

Use limb restraints to prevent agitated, combative, or violent patients from harming themselves or others. Frequently, the use of restraints can be delayed while verbal deescalation techniques are attempted (see “Deescalation Techniques,” earlier). However, if a patient is deemed an immediate threat to himself or others, restrain him without delay. Patients with altered mental status may require limb restraints so that diagnostic testing can be completed or appropriate treatment rendered, or both. Use limb restraints also to prevent patients from interfering with devices, such as endotracheal tubes, cardiac monitors, and indwelling intravenous lines and catheters.

Procedure

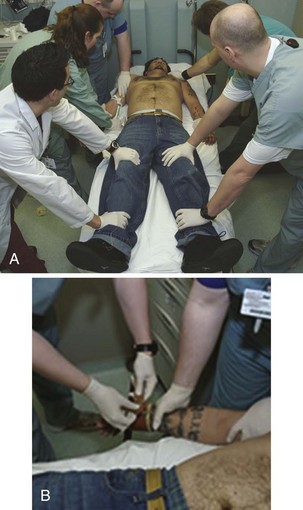

Use a minimum of five people, all trained in restraint techniques and patient safety, to restrain the patient if possible (Fig. 70-8). This show of force may help discourage the patient from resisting and is an important part of the restraint process. The individuals making up the restraint team may include clinicians, nurses, technicians, and police or hospital security. When possible, undress and place the patient in a hospital gown before attempting to apply physical restraint. When this is not practical, restrain the patient, but promptly search for weapons and potentially harmful belongings. Confiscate these items and account for them in accordance with institutional policies.

Always restrain patients in the supine rather than the prone position because the prone position increases the risk for suffocation. Assign one person to hold each limb firmly against the stretcher by applying direct pressure proximal to the elbows and knees. The fifth member of the team places restraints around the wrists and ankles (Fig. 70-9). Control above the elbows and knees reduces the risk for injury to these joints and concentrates force closer to the patient’s center of gravity for better control.

If four-point rather than five-point restraints are applied (i.e., use of extremity restraints only), consider placing one arm up alongside the head and the opposite arm down along the side of the body. In this position it is less likely the patient will be able to overturn the stretcher.16

Once the patient has been safely restrained, frequently assess pulses, capillary refill, skin color and temperature, and motor and sensory function. Reevaluate frequently in accordance with your institution’s policies and procedures because this is key to preventing complications. In general, restraints should have well-defined time limits and should be removed as soon as the patient’s condition has changed sufficiently that the patient is no longer a threat to self or others. For further details regarding rules, regulations, and recommendations for restraint procedures and patient assessment, the reader is referred to the JCAHO website at www.jointcommission.org.

Complications

Increased Agitation: For some patients, placement in physical restraints is so emotionally disturbing that it actually increases agitation and combative behavior. Patients who continue to struggle despite restraints are at risk for a number of potentially serious adverse events, including skin damage, ischemia, metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, hyperthermia, and even death (see “Other Complications,” later). In these patients the addition of chemical sedation is highly recommended (see “Chemical Restraint,” later). In contrast, the use of extremity restraints alone is often effective in an alcohol-intoxicated patient because the natural progression of alcohol intoxication is sedation and sleep. Intoxicated patients may benefit from a brief period of observation before a decision is made to administer chemical sedation. Most of these patients will fall asleep, thereby obviating the need for sedation and the accompanying risks.

Local Skin Complications: Restraints may cause skin irritation or breakdown. Risk factors include restraints that are too tight and those that have been left on for prolonged periods. Leather restraints are more likely than soft restraints to cause skin damage, particularly in patients who continue to struggle despite being placed in restraints. To help prevent skin complications, use soft restraints whenever possible, avoid overly tight restraints, limit restraint time, and reevaluate the patient frequently. In addition, use chemical restraint judiciously to help avoid skin damage in patients who continue to struggle. It is important to not ignore a patient’s complaints of restraint pain without first evaluating the possibility of an adverse event.

Vascular Compromise: Restraints have the rare potential to impede blood flow to the hands and feet. In extreme cases, this could result in ischemia of the distal end of the extremity. Ischemia is more likely to occur in patients whose restraints are placed too tightly and in those in whom swelling develops as a result of an occult injury. Struggling against the restraints may further increase this risk. A thorough search for occult injuries, attention to proper fit, and limited restraint time will help avoid ischemia. Frequent assessment of pulses, capillary refill, skin color and temperature, and motor and sensory function is also extremely important. As mentioned previously, it is also important to not ignore a restrained patient’s complaints regarding extremity pain without first evaluating for the possibility of ischemia.

Respiratory Compromise: Restraints may impair respiratory mechanics in some patients. This is more likely to occur in patients restrained in the prone or hog-tied positions and in those with underlying pulmonary disease.26–30 Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may not tolerate a fifth-point restraint across the chest. Avoid respiratory complications by not restraining patients in the prone or hog-tied position. In addition, use adequate chemical sedation to help negate the need for a supplemental restraint belt in patients with underlying COPD.

Positional Asphyxia: Positional asphyxia is a poorly elucidated respiratory complication often attributed to the use of restraints that results in asphyxia and eventually death. The specifics of respiratory embarrassment secondary to physical restraint are vague and unproven and have not been reproduced in volunteers, who do not experience severe pulmonary compromise from restraint. Thus, though often implicated, the exact contribution of restraint to sudden death is unclear. Obesity, underlying cardiac and pulmonary disease, prone positioning, and concurrent stimulant use are thought to be contributing factors.26,28,30–33 The hog-tied position (see Fig. 70-7), in which a patient’s hands and feet are bound behind the back, places a patient at theoretical risk for positional asphyxia and should therefore not be used in the ED.26–28,33–36 Placing restrained patients in the supine position and frequently reevaluating them will help prevent positional asphyxia. Continuous monitoring of respiratory status, including oxygenation and tidal volume, is indicated in all physically restrained and chemically sedated patients, especially those with obesity, COPD, or intoxication from stimulant drugs.

Cocaine-Associated Agitated Delirium: Cocaine-associated agitated delirium is a syndrome consisting of hyperthermia with delirium and severe agitation that can progress to multisystem failure, coagulopathy, respiratory arrest, and death.28,30,32,34,37 Much of the pathology may be due to cocaine alone, but restrained patients appear to be at particularly high risk for this syndrome. The syndrome was first described in 1985, but its incidence increased significantly in the 1990s because of the popularity of crack cocaine.34,35

The pathophysiology of cocaine-associated agitated delirium is a complex process involving downregulation of dopamine receptors with subsequent dopamine excess during times of cocaine binges.34,38–40 When patients with cocaine-associated agitated delirium are restrained, especially in the prone position, interference with normal respiratory mechanics increases the likelihood of hypoventilation, hypercapnia, and hypoxemia and ultimately leads to asphyxia and death. It has also been suggested that the stress caused by the restraining process increases the risk for fatal cardiac arrhythmias secondary to catecholamine surge in an already cocaine-sensitized myocardium.34 Chronic stimulant use leads to adrenergic-induced cardiomyopathy, which is often clinically silent until the individual is severely stressed. The potential for malignant arrhythmias is unknown, but they have been implicated in some cases of sudden death in restrained patients.

Metabolic Acidosis: In patients who have been restrained, continued agitation and struggling can lead to severe metabolic acidosis.37 Their pH is often lower than 7.0. The etiology of this acidosis is unclear but probably involves the production of lactic acid from physical exertion compounded by sympathetic-induced vasoconstriction. Such vasoconstriction may result from agitation or cocaine (and other stimulant) use and is believed to enhance exercise-induced lactic acidosis by impeding clearance of lactate by the liver.41,42 In some patients the buildup of lactate is further increased by the presence of psychosis and delirium, which may alter pain sensation and allow exertion far beyond normal physiologic limits.37 In addition, some restraint positions (e.g., prone, hog-tied) may not allow adequate respiratory compensation, thereby resulting in further enhancement of the acidosis. A common scenario is an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in which a severely agitated individual suddenly stops struggling and experiences a bradycardic, asystolic death that is not immediately recognized. Such patients may have been subdued by force, by TASER, or by mace or pepper spray, which has led to unproven speculation that these interventions may have caused the change in patient status.

Regardless of the etiology, profound metabolic acidosis has been associated with cardiovascular collapse and sudden and unexpected death in restrained patients.37 Individuals suffer a bradycardic, pulseless electrical activity, asystolic cardiac arrest, and resuscitation is unlikely once cardiac arrest ensues. Patients who remain combative despite restraints, especially those who have used cocaine or other sympathomimetic agents, are at particularly high risk for death.37 Clues to the presence of metabolic acidosis include severe agitation, abnormal vital signs (e.g., persistent tachycardia, tachypnea, and hyperpyrexia), and decreased or concentrated urine output despite adequate intravenous fluid administration. Laboratory testing, including arterial blood gas analysis, serum electrolytes, and serum creatine phosphokinase, is recommended in patients with signs and symptoms suggestive of metabolic acidosis and in those with potentially lethal co-ingestion (e.g., salicylates and toxic alcohols).

Restrained patients with severe metabolic acidosis should receive aggressive saline hydration and sedation with benzodiazepines to counteract the sympathetic hyperactivity.37 The utility of sodium bicarbonate is unknown and it is probably best reserved for patients with a pH below 7.0.

Chemical Restraint

Chemical restraint, more aptly termed chemical sedation, describes the act of quelling an agitated patient by the administration of approved sedative-hypnotic, antipsychotic, or dissociative medications. Early, liberal use of appropriate anxiolytic and sedating medications permits thorough evaluation of a patient’s medical condition. In some cases, administration of anxiolytic drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines) may be the optimal treatment of a person with an undifferentiated delirious state such as delirium tremens.43 This is supported by Khan and associates, who identified an association between the use of physical restraint and death in patients with delirium tremens.44 Although a clear causal relationship between restraint and death is lacking, early use of chemical sedation may be safer than physical restraint for treatment of an undifferentiated delirium.

The CMS states that chemical restraint is “a medication used to control behavior or to restrict the patient’s freedom of movement and is not a standard treatment for the patient’s medical or psychiatric condition.”8 The JCAHO defines chemical restraint as “the inappropriate use of a sedating psychotropic drug to manage or control behavior.”15 These definitions lack perspective on the use of chemical sedation in the ED, where these medications are typically used after all other measures fail and the health and safety of the patient or staff are threatened. Such statements do not reflect standard care in the ED and should not be interpreted as prohibition of the appropriate short-term use of chemical sedation.

The pathogenesis of agitation is poorly understood; however, the advent of anxiolytic and antipsychotic medications has revolutionized the treatment of acute agitation. Not only has sedation become safer, but many of these new agents also have the added benefit of treating underlying psychotic states.4 Benzodiazepines, with rare exception, have replaced barbiturates for the treatment of acute agitation. Recently, intramuscular preparations of “atypical antipsychotic” medications such as olanzapine, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole have provided additional treatment options for rapid control of acute psychosis.45,46

Oral administration of a medication implies consent on behalf of patients since they must cooperate to ingest it. Previous reports have shown that patients prefer oral formulations of medications during the treatment of psychotic episodes.47 Furthermore, patients may feel as though they are participating in their own care plan.48 Oral lorazepam and oral risperidone have demonstrated increased efficacy when compared with the intramuscular administration of haloperidol.49 However, in the ED setting, where rapid tranquilization is usually the goal, medications are typically administered IV or intramuscularly (IM). Obtaining early intravenous access allows titration of rapidly acting medications but may not be possible in some patients. When intravenous access is not possible, intramuscular administration is recommended and in some cases has been shown to be as efficacious and safe as intravenous administration.50 Other routes (oral, transmucosal) may be used when parenteral administration is not practical or feasible.

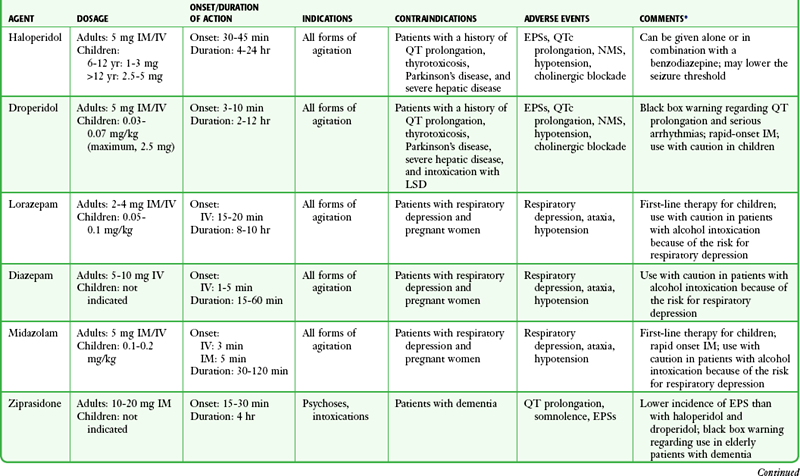

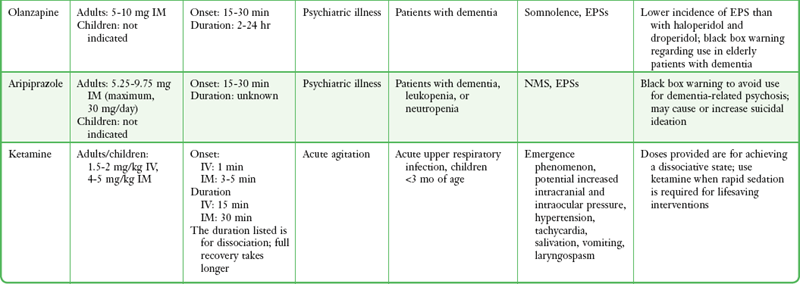

An ideal drug for chemical sedation in the ED should have multiple routes of administration (e.g., intravenous, intramuscular, transmucosal), a rapid onset of action, negligible hemodynamic effects, and a good safety record with minimal adverse effects. Although no medication fits this profile perfectly, with proper patient assessment and careful drug selection, most ED patients can be rapidly and safely sedated. The remainder of this chapter discusses the safety, efficacy, side effect profile, and recommended dosages of the medications most commonly used for chemical sedation. Recommendations for drug selection are also discussed (Table 70-1).

TABLE 70-1

Drugs Used for Chemical Restraint in the ED

*Many of the caveats concerning the safety and efficacy of long-term use cannot be equated to short-term ED use. These medications are currently often used in doses far exceeding those recommended by the manufacturer or under other clinical circumstances; safety and efficacy for short-term sedation have been demonstrated in clinical ED practice.

Other Methods of Drug Delivery

Under most circumstances. sedative medications are best administered IV. A peripheral vein is adequate but may be difficult to access or maintain in a struggling patient. Although an indwelling catheter is preferable, to titrate escalating doses, the first dose may be directly administered into a peripheral vein via a syringe/needle, so-called mainlining (Fig 70-10). A large extremity vein in the arm or leg is usually available if the extremity can be adequately immobilized. The external jugular vein presents another route. The head can often be more easily stabilized than a muscular extremity, and the external jugular vein is usually quite prominent in a struggling patient. Note that some antipsychotics, such as olanzapine and ziprasidone, have indications only for use IM. Haloperidol is universally administered IV, although it has no formal indication for this route. Intranasal midazolam is another alternative route of administration that may have prehospital utility.

Neuroleptic Agents

Neuroleptic medications or “typical antipsychotics” have been used safely and effectively for years to manage patients with undifferentiated agitated delirium in the ED. The antipsychotic effects of neuroleptic agents do not usually take place for 7 to 10 days, but the onset of sedation is rapid, thus making them useful to calm an acutely agitated patient. Potent neuroleptic agents such as haloperidol and droperidol are preferred because they lack tolerance after repeated uses, have a low addiction potential, and possess a high therapeutic index. Low-potency neuroleptics such as chlorpromazine are less desirable because of a higher incidence of hypotension, seizures, and anticholinergic effects.51

Contraindications: Haloperidol and droperidol are contraindicated in patients with thyrotoxicosis (neurotoxicity may develop), Parkinson’s disease, or severe hepatic disease. These drugs can lower the seizure threshold, so they should be used with caution or be avoided altogether in patients with a history of seizures or those who may be at known risk for the development of seizures (i.e., meningitis, sympathomimetic intoxication). Nevertheless, droperidol has been used safely to manage patients with known seizure disorders.52 In addition, like all neuroleptic agents, haloperidol and droperidol can cause QT prolongation. Therefore, they should be used with caution in patients at risk for QT prolongation and torsades de pointes (Box 70-4). Droperidol has also been associated with serotonin syndrome in patients taking lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and should be avoided in these patients.51,53

Adverse Effects: Adverse effects common to all neuroleptic agents include extrapyramidal symptoms (EPSs), QTc prolongation, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), hypotension, and cholinergic receptor antagonism.

A potentially deadly, but exceedingly rare effect of neuroleptic drug use is prolongation of the QTc interval, which can lead to torsades de pointes, a polymorphic ventricular arrhythmia that can progress to ventricular fibrillation and sudden death.4 Droperidol has been the most publicized agent associated with QTc prolongation. It is currently the only neuroleptic agent that has received a “black box warning” for its propensity to cause QTc prolongation and sudden death.54 In addition, a number of case reports and small case series have documented QTc prolongation and torsades de pointes after the administration of haloperidol.55 Risk factors for QTc prolongation and torsades de pointes are listed in Box 70-4.

Patients in whom symptoms of NMS develop exhibit autonomic instability, including rigidity of the extremities, hyperthermia, and delirium. Treatment includes cooling measures, sedation with benzodiazepines, and in severe cases, bromocriptine, dantrolene, neuromuscular paralysis, and endotracheal intubation.51

Haloperidol: Haloperidol is a neuroleptic and a butyrophenone. It is categorized as a high-potency neuroleptic because of its strong antidopaminergic activity. The antidopaminergic activity is responsible for both its intended effects against delusions, hallucinations, and psychomotor agitation and its unintended parkinsonian symptoms. Administration of haloperidol both alone and in combination with benzodiazepines has been evaluated in a large number of clinical trials.56–61 These studies have demonstrated the use of haloperidol IM to be both safe and effective for the management of acute agitation from virtually any cause.

Dosage and Administration.: Haloperidol can be administered PO, IV, and IM and has a low incidence of oversedation regardless of which route is chosen.4 Despite a lack of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use IV, haloperidol is typically administered IV. The recommended starting dosage to achieve sedation is 5 mg IM or IV, titrated to effect. There is no absolute maximum dose, and in cases of severe EXDS, doses of 10 to 30 mg are common. Occasionally, extrapyramidal reactions occur but are easily treated. The dose should be halved when administered to elderly patients. In children 6 to 12 years of age, the dosage is 1 to 3 mg IM every 4 to 8 hours with a maximum of 0.15 mg/kg/day. Children older than 12 years can receive the adult dosage. Haloperidol administered IM has a peak clinical effect within 30 to 45 minutes and may last up to 24 hours when given for acute agitation. Haloperidol is metabolized by the liver and excreted by the kidneys.62

Droperidol: Droperidol, an analogue of haloperidol, is a high-potency butyrophenone with rapid sedating effects. It also possesses significant antidopaminergic activity. Droperidol acquired FDA approval in 1970 first as an antiemetic and antipsychotic agent. Soon thereafter, psychiatric EDs found it useful for chemical sedation.63 Many physicians prefer droperidol to haloperidol because of its more rapid onset and shorter duration of action.

Use of droperidol as a chemical sedative continued until 2001, at which time the FDA issued a “black box” warning regarding the potential for fatal dysrhythmias.64 Many hospitals and pharmacies subsequently sought to restrict or prohibit its use. However, two large retrospective studies encompassing more than 15,000 patients failed to demonstrate increased morbidity or mortality associated with the use of droperidol for the management of acute agitation.52,63 This controversy prompted an independent review of the data submitted to the FDA that led to the black box warning. The authors of this review found a number of anomalies and duplicate reports. They concluded that droperidol is a safe drug when used at the recommended dosage (i.e., 5 to 10 mg).65 Despite an apparent lack of evidence behind the black box warning, use of droperidol has declined dramatically.66

Studies comparing a variety of agents for rapid sedation have found that droperidol provides more rapid and effective control than do lorazepam,67 haloperidol,56 midazolam,68,69 and ziprasidone.68 In addition, droperidol has been proved to be safe in patients with head injuries, alcohol and cocaine intoxication, and seizure disorders.52

Benzodiazepines

All benzodiazepines enhance the neurotransmission of γ-aminobutyric acid and thereby result in anxiolysis, sedation, hypnosis, and muscle relaxation. This combination makes them an excellent choice for tranquilization of agitated patients. Because of an excellent safety profile, benzodiazepines are an excellent choice for sedating medically undifferentiated patients. The differences in clinical effects (e.g., onset, duration, adverse effects) are primarily related to dosage, route of administration, and pharmacokinetics. Benzodiazepines can be used as single agents or in combination with an antipsychotic drug. Lorazepam and midazolam are the benzodiazepines most commonly used for chemical sedation. This is probably due to their rapid and predictable absorption when given IV or IM, as well as a long history of safety and efficacy. Unlike neuroleptics, benzodiazepines do not treat underlying psychiatric disorders. Some clinicians prefer to administer diazepam IV for the treatment of delirium related to sedative-hypnotic withdrawal.43

Contraindications: There are few contraindications to the use of benzodiazepines as a chemical sedating agent. Because of the possibility of respiratory depression, use benzodiazepines with caution in patients in respiratory distress.

Adverse Effects: As discussed previously, benzodiazepines may cause respiratory depression. Additionally, hypotension, deep sedation, and paradoxical agitation have been reported. However, when administered in the doses recommended for agitation, adverse events are rare, thus making benzodiazepines the drugs of choice in most circumstances.

Respiratory compromise is dose dependent and typically occurs only in the presence of other respiratory depressants.71,72 Because of an increased risk for respiratory depression, administer benzodiazepines cautiously to elderly patients and those with chronic pulmonary diseases such as apnea and COPD. In healthy patients, particularly those suffering from agitated delirium, respiratory depression is very unlikely to occur, even when large doses of benzodiazepines are used. If available, end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring (e.g., capnography) may assist the practitioner in detecting the onset of respiratory depression before it becomes clinically significant.73,74

Lorazepam: Lorazepam is the benzodiazepine most frequently studied for the management of acute agitation. It enjoys popularity as part of the well-known “five and two” treatment regimen, which consists of haloperidol, 5 mg IM, and lorazepam, 2 mg IM.75 In a number of clinical trials, lorazepam was shown to be an effective drug for rapid chemical sedation.57,60,61,67 In these studies lorazepam had no extrapyramidal effects and was better tolerated than the neuroleptics. However, when compared with haloperidol, droperidol, midazolam, and a combination of haloperidol and lorazepam, the onset of sedation after administering lorazepam IM was more delayed.57,60,67

Dosage and Administration.: When used alone, lorazepam is usually given in 2- to 4-mg doses and can be administered PO, sublingually, IM, IV, or rectally. No maximum dose has been established. Following an injection of lorazepam IM, adequate sedation is usually achieved in 30 to 45 minutes.67 When given IV, sedation occurs in 15 to 20 minutes.60 The elimination half-life is 12 to 15 hours, which produces a duration of effect of 8 to 10 hours. This makes lorazepam a better choice when long-term sedation is the goal. Lorazepam is rapidly conjugated to an inactive glucuronide. This does not require involvement of the cytochrome P-450 system, so lorazepam has few drug-drug interactions. Preparations of lorazepam intended for use IV or IM must be refrigerated, thus potentially limiting its use in underdeveloped countries and in the prehospital setting.4

Midazolam: Midazolam has been shown to be effective for rapid sedation.59,60,68,69 It has a more rapid onset and shorter duration of action than other benzodiazepines do, which makes it a good choice when rapid short-term sedation is desired. Midazolam also compares favorably with haloperidol, droperidol, and ziprasidone for the treatment of acute agitation in the ED. 59,60,69 With the exception of droperidol, which had a similar time until onset (5 to 10 minutes), midazolam had a more rapid onset of sedation than the other drugs did in these studies. The studies also noted that midazolam, as expected, had a shorter duration of sedation.

Dosage and Administration.: The initial dosage for an agitated adult is 5 mg IV or IM, and it may be repeated at 5- to 10-minute intervals. No maximum dose has been established. Nasal administration is also an option. The onset of sedation occurs approximately 3 minutes after intravenous administration, 5 minutes after an intramuscular injection, and 15 minutes after nasal administration. Midazolam is hydroxylated by the cytochrome P-450 system to its primary metabolite, α-hydroxymidazolam, which undergoes glucuronide conjugation before being excreted in urine. Its duration of action is between 30 and 120 minutes and does not vary significantly by route of administration.60,76

Diazepam: Diazepam has a long history of safe use in the management of agitated delirium, especially delirium tremens and alcohol withdrawal.43,77 For patients experiencing delirium tremens the usual dose is 5 to 10 mg IV every 5 to 10 minutes until the desired level of sedation is achieved (lower doses are appropriate for less severe agitation or agitation from other causes). No maximum dose has been established, and doses of up to 2000 mg have been used safely over a 24-hour period in patients experiencing delirium tremons.43,78 Because of erratic absorption, intramuscular administration of diazepam is not recommended. Following the administration of diazepam, peak sedation is reached in about 5 to 6 minutes, which allows additional titrated doses if the desired clinical effect is not achieved initially.

Atypical Antipsychotic Agents

Atypical antipsychotic agents have high affinity for 5-HT (serotonin) receptors and less affinity for D1 and D2 receptors. As a result, they have a lower incidence of EPSs than haloperidol and droperidol do.62 In the past, medications in this class were available only in an oral formulation, thus limiting their use in the management of acute agitation. Recently, formulations of ziprasidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole intended for administration IM have been developed. When administered IM, all three drugs are effective for the treatment of acute agitation.79 Moreover, the combination of administration IM and the low incidence of EPSs makes these newer agents an attractive option for rapid sedation of ED patients with undifferentiated agitation. This is particularly true for patients with a history of mental illness, for whom this class of medications is now considered to be appropriate first-line management.80

Contraindications: In 2005, a metaanalysis of placebo-controlled trials demonstrated an increased risk for death associated with the atypical antipsychotic agents used to treat elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis.81 This report led the FDA to issue a black box warning regarding the use of atypical antipsychotics for “behavioral disorders” in elderly patients with dementia. Such warnings have not resulted in the prohibition of such agents for short-term use in the ED. The FDA has also advised caution with ziprasidone because of its tendency to prolong the QTc interval, especially when used in patients taking other drugs or with medical conditions that increase the risk for prolongation of the QTc interval (see Box 70-4).81 Ziprasidone prolongs the QTc interval more frequently than haloperidol, droperidol, and olanzapine do,4 but the degree of prolongation is considered minor and is rarely greater than 500 msec.82 To date, there have been no clinical reports of adverse events as a result of QTc prolongation with the short-term ED use of atypical antipsychotic agents. Experience with these agents in undifferentiated acutely agitated patients in the ED is limited, but their use is increasing, and although initial reports are supportive, they are not yet definitive.

Adverse Effects: Atypical antipsychotic agents may cause somnolence, EPSs (though less often than with haloperidol and droperidol), QTc prolongation, and rarely, anticholinergic symptoms and NMS.

Ziprasidone: Ziprasidone is a benzylisothiazolylpiperazine antipsychotic agent whose effects are the result of dopamine and serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonism.4,79,83 This was the first atypical antipsychotic agent available in a fast-acting preparation administered IM. In a double-blind, randomized study, Martel and coworkers68 noted that ziprasidone was as effective as midazolam and droperidol in controlling acute agitation. Patients receiving ziprasidone and droperidol took longer to be sedated (30 minutes as compared with 15 minutes for midazolam) but were more deeply sedated at 60 and 120 minutes.68 In a prospective, open-label study, ED patients receiving ziprasidone exhibited progressive improvement in anxiety, hostility, and cooperativeness starting at 15 minutes and continuing through the 90-minute study period.46 In an observational study of agitated psychiatric ED patients with nonspecific psychosis, alcohol intoxication, or substance-induced psychosis, ziprasidone, 20 mg IM, was effective in sedating patients as early as 15 minutes.84 Ziprasidone has not been approved by the FDA for the treatment of dementia-related psychosis.83

Dosage and Administration.: The recommended dosage of ziprasidone is 10 mg IM, which can be repeated at 2 hours, or 20 mg IM, which may be repeated at 4 hours. The drug reaches peak plasma concentrations in 30 to 45 minutes and has an elimination half-life of 2 to 4 hours. Following an intramuscular injection, sedation usually begins within 15 to 30 minutes and peaks at around 2 hours. The clinical effects usually last at least 4 hours.85

Olanzapine: Olanzapine is a second-generation thienobenzodiazepine antipsychotic agent that is thought to exert its effects through antagonism of both dopamine and serotonin type 2 receptors. Olanzapine in an intramuscular formulation has recently been approved by the FDA for the treatment of agitation in acutely psychotic patients. Intramuscular olanzapine is comparable to haloperidol or lorazepam monotherapy for acute agitation associated with schizophrenia and dementia58,86,87 and superior to lorazepam monotherapy in the management of agitation associated with bipolar disorder.88 To date, there have been no clinical trials using intramuscular olanzapine for undifferentiated agitation in the ED, but its use is increasing.

Dosage and Administration.: The recommended dosage is 5 to 10 mg IM. Additional doses may be considered 2 to 4 hours after the preceding dose with a maximum recommended dose of 30 mg/day IM. Olanzapine reaches peak plasma concentrations in 15 to 45 minutes and has an elimination half-life of 21 to 54 hours. The onset of sedation usually begins 15 to 30 minutes after intramuscular administration and typically lasts at least 2 hours. In some patients, the clinical effects have lasted as long as 24 hours. The drug is metabolized via direct glucuronidation and cytochrome P-450–mediated oxidation.89

Aripiprazole: Aripiprazole is an atypical antipsychotic that acts at both serotonin and dopamine receptors. Rates of EPSs are lower than with other antipsychotics, which may be a result of the drug’s partial agonistic activity at dopamine receptors. Intramuscular administration has been approved for acute agitation related to schizophrenia and bipolar mania. To date, there have been no clinical trials using aripiprazole IM for undifferentiated agitation in the ED.

Dissociative Agents

Ketamine: Ketamine is a dissociative agent that has been used safely throughout the world for major surgery and with minimal monitoring.90 Many clinicians are familiar with ketamine as a safe and rapidly effective dissociative agent for tracheal intubation and for children undergoing painful procedures in the ED, where its use has become standard practice. Ketamine has no significant adverse effects on blood pressure or respiration. It inhibits the reuptake of catecholamines promoting bronchodilation and increases in both heart rate and blood pressure. Commonly raised as a caution, there is no proven issue with ketamine causing harmful increased intracranial pressure.91,92 Possible side effects of ketamine include salivation, vomiting, laryngospasm, and emergence phenomena consisting of nightmares, short-lived bizarre thoughts, and hallucinations. Fortunately, emergence phenomena have not been described as significant issues following ED use.

Although ketamine is not commonly used to control agitated and delirious patients, the drug’s pharmacologic profile lends itself to use for acute agitation. For example, ketamine has been used successfully in aeromedical transport as a sedative agent for patients with agitation.93 It has also been effective in the prehospital management and transport of patients with severe EXDS and in combative trauma patients (including those with head injury),94 acutely agitated cocaine-intoxicated patients,95 and agitated suicidal patients.96

Dosage and Administration.: The dose of ketamine to produce profound dissociation is 1.5 to 2.0 mg/kg IV or 4 to 5 mg/kg IM. Intramuscular administration is ideal in the ED when access for intravenous administration is not readily available. The anterior aspect of the thigh is a preferred site of injection for rapid tranquilization. Time of onset may vary slightly, but both routes have a rapid onset of action (30 seconds IV, 3 to 5 minutes IM). At the current time, ketamine is undergoing resurgence in popularity among emergency physicians, and the role of ketamine for the chemical control of acutely agitated and delirious patients in the ED is evolving.

Choosing the Best Agent

Undifferentiated Agitation: The safest agent for undifferentiated agitation in the ED has traditionally been a benzodiazepine administered IV, often combined with judicious doses of haloperidol. Ketamine and newer atypical antipsychotics are gaining favor, but their track record is short. Administering escalating doses of benzodiazepines seem to be a prudent choice in such circumstances when the clinician is comfortable prescribing a drug from this class. There is little concern for respiratory or cardiovascular depression with the prudent use of carefully titrated intravenous benzodiazepines in the monitored setting. Figure 70-1 suggests a possible management approach to an acutely agitated patient in the emergency setting. It must be emphasized that benzodiazepine doses considered exceeding high or even toxic by other standards are routinely and safely administered in the ED when aggressive sedation and chemical control are mandated as clinical priorities. In severe cases, benzodiazepines alone will not be totally effective.

Agitation Caused by Alcohol and Drugs of Abuse: For patients who are suspected of intoxication from alcohol or other sedative agents, haloperidol, droperidol, or ziprasidone will provide rapid, safe, and effective tranquilization.52,63,69 Benzodiazepines should be administered with caution to alcohol-intoxicated patients and those taking sedative agents because of the possibility of respiratory depression.71,72 In contrast, benzodiazepines are the drugs of choice in patients who are agitated as a result of alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal. Large doses may be required, and the safety profile is wide. Patients who are agitated because of sympathomimetic agents such as cocaine or methamphetamines or hallucinogens such as PCP or LSD may be treated safely with large doses of benzodiazepines, butyrophenones, or a combination of the two.52,57,67 Droperidol has been associated with serotonin syndrome in patients taking LSD and should be avoided in these patients.51,53

Agitation Caused by Medical Illness: In patients whose agitation is due to medical illness, treatment should be aimed at correcting the underlying pathology. If rapid sedation is required, typical antipsychotics or benzodiazepines should be used as first-line therapy. If the patient is frail or elderly or is known to have renal impairment, consider using smaller doses of a single agent.

Agitation Caused by an Underlying Psychiatric Disorder: Patients with an established psychiatric history and agitation attributed to schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or the manic phase of bipolar disorder may be treated with typical antipsychotic agents, atypical antipsychotic agents, or benzodiazepines. However, a growing body of evidence seems to support the use of atypical antipsychotic agents in this circumstance.46,58,68,84,86,87,95,97,98

Agitation in Children: Because of years of experience and a proven safety record, benzodiazepines are considered first-line therapy for the management of agitation in children. The intramuscular dose of lorazepam is 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg and the intramuscular dose of midazolam is 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg. Neuroleptic agents have also been used to manage agitation in children. The intramuscular dose of haloperidol is 0.025 to 0.075 mg/kg, with a maximum dose of 2.5 mg. Children older than 12 years can receive the adult dose, usually 2.5 to 5.0 mg IM (see Table 70-1). Although droperidol is a highly effective drug for rapid sedation of adults, there is a paucity of literature supporting its use in children. The pediatric dose of droperidol is 0.03 to 0.07 mg/kg with a maximum initial dose of 2.5 mg.51 Combination therapy is not generally recommended for children.75

Agitation in Pregnancy: Psychotropic and anxiolytic medications should be used during pregnancy only when the potential risk to the fetus from exposure is outweighed by the risk of not treating the disorder in the mother.99 Based on years of accumulated clinical experience but very few scientific data, conventional antipsychotic agents such as haloperidol and droperidol (pregnancy class C) are recommended to control agitation in pregnant women.100 In pregnancy, benzodiazepines (pregnancy class D) may be associated with teratogenicity (especially craniofacial abnormalities) when used for an extended period.101 Although clear causation has not been proved, benzodiazepines are generally avoided during the first trimester to minimize the risk for fetal malformation.102 Judicious benzodiazepine administration should be considered a viable option in the acute ED setting in the second and early third trimesters.

Agitation in Older Patients: Patients 65 years or older are particularly susceptible to adverse drug reactions because of coexisting medical illness, use of multiple prescription medications (which increase the risk for drug-drug interactions), and age-associated changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Research suggests that conventional antipsychotic medications such as haloperidol and droperidol are safe and effective for both psychotic symptoms and nonpsychotic agitated behavior.103 Low doses (e.g., half the usual dose) of benzodiazepines can also be used but require close observation for respiratory depression. Continued use (>8 to 10 weeks) of atypical antipsychotic agents has been associated with increased rates of death in cases of dementia-related psychosis.81

Conducted Electrical Weapons

CEWs, including TASERs (TASER International, Inc., Scottsdale, AZ) and stun guns, are used by law enforcement agencies throughout the world. These nonlethal weapons use a temporary high-voltage low-current electrical discharge to overcome a body’s voluntary muscle-triggering mechanisms, which results in widespread involuntary muscle contractions that incapacitate the victim. The current is delivered by direct contact with a handheld device (i.e., electric shock prods) or via a small dart-like electrode fired from a gun using small gas charges (e.g., TASER) similar to some air rifle propellants. There are also electrical weapons that cause intense pain without incapacitating the target, so-called drive stun devices. Law enforcement and correctional personnel typically use drive stun devices as a pain compliance technique. A TASER may deliver approximately 1200 V but can reach up to 50,000 V across clothes without direct skin contact.104

The exact street scenario of EXDS, physical restraint, and a TASER-linked death will probably never be studied with unchallenged scientific accuracy, and hence one is left with animal and human volunteer data to intuit the cause and effect of untoward events. Despite claims of lethality in the press, emotional testimony and unscientific reports from human rights organizations, and poorly documented claims in case reports, there have been no documented deaths directly and indisputably attributable to a TASER discharge in humans.105 Volunteer studies and animal models fail to provoke cardiac arrest or significant cardiopulmonary or metabolic derangements after standard electrical discharges, even when animal models include stimulant toxicity and human volunteers are exercised to exhaustion.104 Nevertheless, CEWs have been temporally linked to a number of fatalities.104–106 The majority of these cases involved sympathomimetic drug intoxication (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamines), prolonged physical exertion, or both.106 The role of severely altered metabolic and autonomic parameters, drug intoxication, or underlying comorbid conditions, including cardiomyopathy, obscures the exact contribution of CEW use in unexpected deaths. A complete discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this chapter, but it has been well reviewed elsewhere.107 The darts from a CEW often penetrate the skin and must be removed, so the remainder of this section focuses on the procedure for removing embedded TASER electrodes.

Electronic Control Devices

TASER is an acronym for “Thomas A. Swift’s Electric Rifle” and has been in existence since the early 1990s (Fig. 70-11). More than 11,000 law enforcement, correctional, and military agencies in 44 countries deploy TASER devices, and many municipalities in the United States allow civilians to purchase and carry these weapons for personal protection.108 A TASER uses compressed nitrogen to propel two electrode-tipped barbs at 180 ft/sec at the target. The electrode-tipped barbs are attached to the electric device via two thin 21-foot wires and are similar in size to a No. 8 fishhook measuring 4 mm in length (Fig. 70-12). The barbs may attach to clothing and fail to penetrate the skin, or they may become embedded in skin and must be removed.

Figure 70-11 TASER electrical control device.

Figure 70-12 TASER dart/electrode-tipped barb. Note: the groove in the shaft (arrow) lines up with the barb tip to aid in removal.

Removal Techniques: Barbs embedded in soft tissue can easily be removed with direct pressure. Place one hand on the skin surrounding the barb to hold the skin taut and use the other hand to apply direct pressure to the barb108,109 (Fig. 70-13). If the patient cannot tolerate the procedure, inject a small amount of local anesthetic near the barb and use a No. 11 scalpel blade to cut down through the soft tissue to the tip of the barb.108 Because of the small size and linear shape of the barb, there is no need to advance the barb through the skin to remove the tip as is commonly performed during the removal of fishhooks.109 After removal, clean and dress the wound (see Chapter 34), but do not suture it. Analgesics (e.g., nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, acetaminophen) may be administered.

Complications: Because of the small size of the barb, the risk for significant injury to the heart, lungs, or bowel from a TASER device is small. Theoretical risk for injury to vascular structures and genitalia exists, although no cases have been reported in the literature. There have been case reports of serious intraocular and intracranial injuries resulting from a TASER barb, but these are rare.110–113 A barb embedded in a vascular structure can probably be removed with manual traction followed by direct pressure on the wound because the size of the barb is similar to the size of devices used to obtain central venous access.109 Consultation with a vascular surgeon may be required in complicated cases. Severe involuntary muscle contraction from the electrical discharge has been implicated as a cause of acute thoracic compression fractures.114,115 Based on a literature review in 2011 by Vilke and colleagues, there is currently no indication for routine diagnostic or laboratory testing in asymptomatic patients following short-duration exposure (<15 seconds) to a CEW.116

TASER Use in the ED: While data are difficult to confirm, it has been estimated that about 150 hospitals allow hospital security guards to carry TASERS. Those equipped with TASERS should have specific training, and policies on the use of the TASER in the hospital setting should be in place and training periodically updated. CMS regulations do not disallow TASERS in the hospital, but CMS and most states do not sanction the use of such devices to restrain a patient or to make them comply with medical treatment. Whenever possible, the least restrictive methods should be used to deescalate aggressive behavior, or calm agitated or disruptive individuals, such as a quiet and low-stimulation environment, reasonable bargaining, redirection of the patient, involvement of family, reality orientation, talk down, or a show of force. It is a gray area, indeed, as to when, or to what extent, any intervention is considered necessary to restrain a patient, or to protect a patient or medical personnel from harm. Every situation is somewhat unique so dogmatic approaches cannot be used. When a mentally incompetent or potentially suicidal patient wants to leave the ED against medical advice, and does not have insight into the adverse effects of such an egress, involuntary commitment is initiated. Effective measures are usually initiated by the emergency physician because psychiatric evaluation on such short notice is impractical or unavailable and important decisions must be made immediately with limited data. Such patients may assault those attempting to keep them from leaving the ED in their incompetent mental state, when medical consequences, suicide, or harm to others could be the ultimate outcome.

In one small nonvalidated study, Ho et al117 concluded that the introduction of the TASER into the health care setting (a large urban tertiary care teaching hospital) demonstrated the ability to avert and control situations that could result in injury to medical personnel and patients, by simple TASER presentation or rarely actual use. In that study there was a reduction in personnel injury rates and the contention that one suicide was averted. Further study is required before definitive statements can be made. In summary, the use of the TASER in the ED has not yet been clarified, and there are advocates as well as critics. Any weapon, including the TASER, should not be used to force a patient to comply or to induce restraint in the absence of reasonable suspicion of impending harm or actual assault of medical personnel.

References

1. Lavoie, FW, Carter, GL, Danzl, DF, et al. Emergency department violence in United States teaching hospitals. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:1227–1233.

2. Dubin, W. Evaluating and managing the violent patient. Ann Emerg Med. 1981;10:481.

3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21440403.

4. Battaglia, J. Pharmacological management of acute agitation. Drugs. 2005;65:1207–1222.

5. Weiss, E. Deadly restraint: a nationwide pattern of death. The Hartford Courant. 1998.

6. Public Law No. 100-203, Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987, 22 December 1987. Annu Rev Popul Law. 1987;14:473–475.

7. Standards for restraint and seclusion. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Jt Comm Perspect. 1996;16:RS1–RS8.

8. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Patients’ Rights; Final Rule. Vol 71. No. 236, Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, 2006.

9. Sullivan-Marx, EM, Strumpf, NE. Restraint-free care for acutely ill patients in the hospital. AACN Clin Issues. 1996;7:572–578.

10. American College of Emergency Physicians. Use of Patient Restraints. http://www.acep.org/Content.aspx?id=29836, 2007. [Available at Accessed December 2, 2011].

11. Annas, GJ. The last resort—the use of physical restraints in medical emergencies. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1408–1412.

12. Gregory, RJ, Nihalani, ND, Rodriguez, E. Medical screening in the emergency department for psychiatric admissions: a procedural analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:405–410.

13. Anfinson, TJ, Kathol, RG. Screening laboratory evaluation in psychiatric patients: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14:248–257.

14. Lukens, TW, Wolf, SJ, Edlow, JA, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the diagnosis and management of the adult psychiatric patient in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:79–99.

15. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Restraint and Seclusion: Complying with Joint Commission Standards. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: JCAHO; 2002.

16. Coburn, VA, Mycyk, MB. Physical and chemical restraints. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2009;27:655–667. [ix].

17. Mattson, MR, Sacks, MH. Seclusion: uses and complications. Am J Psychiatry. 1978;135:1210–1213.

18. Schwab, PJ, Lahmeyer, CB. The uses of seclusion on a general hospital psychiatric unit. J Clin Psychiatry. 1979;40:228–231.

19. Erickson, WD, Realmuto, G. Frequency of seclusion in an adolescent psychiatric unit. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983;44:238–241.

20. Fassler, D, Cotton, N. A national survey on the use of seclusion in the psychiatric treatment of children. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1992;43:370–374.

21. Zun, L. The use of seclusion in emergency medicine. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:365–371.

22. Zun, LS, Downey, L. The use of seclusion in emergency medicine. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:365–371.

23. Zun, LS. Evidence-based treatment of psychiatric patient. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:277–283.

24. Zun, LS. A prospective study of the complication rate of use of patient restraint in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:119–124.

25. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Preventing Restraint Deaths. http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/SentinelEventAlert, 1998. [Available at Accessed December 2, 2011].

26. Bell, MD, Rao, VJ, Wetli, CV, et al. Positional asphyxiation in adults. A series of 30 cases from the Dade and Broward County Florida Medical Examiner Offices from 1982 to 1990. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1992;13:101–107.

27. Reay, DT, Fligner, CL, Stilwell, AD, et al. Positional asphyxia during law enforcement transport. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1992;13:90–97.

28. Stratton, SJ, Rogers, C, Green, K. Sudden death in individuals in hobble restraints during paramedic transport. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:710–712.

29. Ross, DL. An analysis of in-custody deaths and positional asphyxiation. Police Marksman. 1996;March/April:16–18.

30. Glatter, K, Karch, SB. Positional asphyxia: inadequate oxygen, or inadequate theory? Forensic Sci Int. 2004;141:201–202.

31. Reay, DT, Howard, JD, Fligner, CL, et al. Effects of positional restraint on oxygen saturation and heart rate following exercise. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1988;9:16–18.

32. Pollanen, MS, Chiasson, DA, Cairns, JT, et al. Unexpected death related to restraint for excited delirium: a retrospective study of deaths in police custody and in the community. CMAJ. 1998;158:1603–1607.

33. O’Halloran, RL, Lewman, LV. Restraint asphyxiation in excited delirium. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1993;14:289–295.

34. Wetli, CV, Fishbain, DA. Cocaine-induced psychosis and sudden death in recreational cocaine users. J Forensic Sci. 1985;30:873–880.

35. Wetli, CV, Mash, D, Karch, SB. Cocaine-associated agitated delirium and the neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:425–428.

36. Kupas, DF, Wydro, GC. Patient restraint in emergency medical services systems. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2002;6:340–345.

37. Hick, JL, Smith, SW, Lynch, MT. Metabolic acidosis in restraint-associated cardiac arrest: a case series. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:239–243.

38. Staley, J, Basile, M, Wetli, C, et al. Differential regulation of the dopamine transporter in cocaine overdose deaths. NIDA Res Monogr. 1994;141:32.

39. Staley, J, Hearn, L, Ruttenber, A, et al. High affinity cocaine recognition sites on the dopamine transporter are elevated in fatal cocaine overdose victims. J Pharm Exp Ther. 1994;271:1678.

40. Staley, J, Wetli, C, Ruttenber, A, et al. Altered dopaminergic synaptic markers in cocaine psychosis and sudden death. NIDA Res Monogr. 1995;153:491.

41. Buzzoto, TM. Severe metabolic acidosis secondary to exertional hyperlactemia. Am J Emerg Med. 1988;6:134.

42. Bethke, RA, Gratton, M, Watson, MA. Severe hyperlactemia and metabolic acidosis following cocaine use and exertion. Am J Emerg Med. 1990;8:369.

43. Gold, JA, Rimal, B, Nolan, A, et al. A strategy of escalating doses of benzodiazepines and phenobarbital administration reduces the need for mechanical ventilation in delirium tremens. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:724–730.

44. Khan, A, Levy, P, DeHorn, S, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with delirium tremens. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:788–790.

45. Tulloch, KJ, Zed, PJ. Intramuscular olanzapine in the management of acute agitation. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:2128–2135.

46. Fulton, JA, Axelband, J, Jacoby, JL, et al. Intramuscular ziprasidone: an effective agent for sedation of the agitated ED patient. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:254–255.

47. Allen, MH, Carpenter, D, Sheets, JL, et al. What do consumers say they want and need during a psychiatric emergency? J Psychiatr Pract. 2003;9:39–58.

48. Rund, DA, Ewing, JD, Mitzel, K, et al. The use of intramuscular benzodiazepines and antipsychotic agents in the treatment of acute agitation or violence in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2006;31:317–324.

49. Currier, GW, Simpson, GM. Risperidone liquid concentrate and oral lorazepam versus intramuscular haloperidol and intramuscular lorazepam for treatment of psychotic agitation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:153–157.

50. Calver, LA, Downes, MA, Page, CB, et al. The impact of a standardised intramuscular sedation protocol for acute behavioural disturbance in the emergency department. BMC Emerg Med. 2010;10:14.

51. Sorrentino, A. Chemical restraints for the agitated, violent, or psychotic pediatric patient in the emergency department: controversies and recommendations. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2004;16:201–205.

52. Chase, PB, Biros, MH. A retrospective review of the use and safety of droperidol in a large, high-risk, inner-city emergency department patient population. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1402–1410.

53. Heard, K, Daly, FF, O’Malley, G, et al. Respiratory distress after use of droperidol for agitation. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:410–411.

54. FDA Public Health Advisory. Deaths with Antipsychotics in Elderly Patients with Behavioral Disturbances. April 11, 2005. Available at http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/advisory/antipsychotics.htm. [Accessed December 2, 2011].

55. Haddad, PM, Anderson, IM. Antipsychotic-related QTc prolongation, torsades de pointes and sudden death. Drugs. 2002;62:1649–1671.

56. Thomas, H, Jr., Schwartz, E, Petrilli, R. Droperidol versus haloperidol for chemical restraint of agitated and combative patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:407–413.

57. Battaglia, J, Moss, S, Rush, J, et al. Haloperidol, lorazepam, or both for psychotic agitation? A multicenter, prospective, double-blind, emergency department study. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15:335–340.

58. Breier, A, Meehan, K, Birkett, M, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled dose-response comparison of intramuscular olanzapine and haloperidol in the treatment of acute agitation in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:441–448.

59. TREC Collaborative Group. Rapid tranquillisation for agitated patients in emergency psychiatric rooms: a randomised trial of midazolam versus haloperidol plus promethazine. BMJ. 2003;327:708–713.

60. Nobay, F, Simon, BC, Levitt, MA, et al. A prospective, double-blind, randomized trial of midazolam versus haloperidol versus lorazepam in the chemical restraint of violent and severely agitated patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:744–749.

61. Alexander, J, Tharyan, P, Adams, C, et al. Rapid tranquillisation of violent or agitated patients in a psychiatric emergency setting. Pragmatic randomised trial of intramuscular lorazepam v. haloperidol plus promethazine. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:63–69.

62. American Society of Health System Pharmacists. Butyrophenones. Bethesda, MD: ASHSP; 2006.

63. Shale, JH, Shale, CM, Mastin, WD. A review of the safety and efficacy of droperidol for the rapid sedation of severely agitated and violent patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:500–505.

64. Food and Drug Administration. Inapsine (droperidol) Black Box Warning. http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm172364.htm, 2001. [Available at Accessed December 2nd, 2011].

65. Mullins, M, Van Zwieten, K, Blunt, JR. Unexpected cardiovascular deaths are rare with therapeutic doses of droperidol. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:27–28.

66. Jacoby, JL, Fulton, J, Cesta, M, et al. After the black box warning: dramatic changes in ED use of droperidol. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:196.

67. Richards, JR, Derlet, RW, Duncan, DR. Chemical restraint for the agitated patient in the emergency department: lorazepam versus droperidol. J Emerg Med. 1998;16:567–573.

68. Martel, M, Sterzinger, A, Miner, J, et al. Management of acute undifferentiated agitation in the emergency department: a randomized double-blind trial of droperidol, ziprasidone, and midazolam. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1167–1172.

69. Knott, JC, Taylor, DM, Castle, DJ. Randomized clinical trial comparing intravenous midazolam and droperidol for sedation of the acutely agitated patient in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:61–67.

70. American Society of Health System Pharmacists. Anxiolytics, Sedatives, Hypnotics. Bethesda, MD: AHFSD; 2006.

71. Bailey, PL, Pace, NL, Ashburn, MA, et al. Frequent hypoxemia and apnea after sedation with midazolam and fentanyl. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:826–830.

72. Wright, SW, Chudnofsky, CR, Dronen, SC, et al. Midazolam use in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 1990;8:97–100.

73. Deitch, K, Miner, J, Chudnofsky, CR, et al. Does end tidal CO2 monitoring during emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia with propofol decrease the incidence of hypoxic events? A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:258–264.

74. Nagler, J, Krauss, B. Capnography: a valuable tool for airway management. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2008;26:881–897. [vii].

75. Allen, MH, Currier, GW, Hughes, DH, et al. Treatment of behavioral emergencies: a summary of the expert consensus guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2003;9:16–38.

76. Nordt, SP, Clark, RF. Midazolam: a review of therapeutic uses and toxicity. J Emerg Med. 1997;15:357–365.

77. Hack, JB, Hoffmann, RS, Nelson, LS. Resistant alcohol withdrawal: does an unexpectedly large sedative requirement identify these patients early? J Med Toxicol. 2006;2(2):55–60.

78. Nolop, KB, Natow, A. Unprecedented sedative requirements during delirium tremens. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:246–247.

79. Zimbroff, DL. Pharmacological control of acute agitation: focus on intramuscular preparations. CNS Drugs. 2008;22:199–212.

80. Allen, MH, Currier, GW, Carpenter, D, et al. The Expert Consensus Guideline Series. Treatment of behavioral emergencies 2005. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11(suppl 1):5–108. [quiz 110-102].

81. Schneider, LS, Dagerman, KS, Insel, P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294:1934–1943.

82. Taylor, D. Ziprasidone in the management of schizophrenia: the QT interval issue in context. CNS Drugs. 2003;17:423–430.

83. Pfizer Inc, Geodon [prescribing information]. New York, 2005.

84. Preval, H, Klotz, SG, Southard, R, et al. Rapid-acting IM ziprasidone in a psychiatric emergency service: a naturalistic study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:140–144.

85. Brook, S. Intramuscular ziprasidone: moving beyond the conventional in the treatment of acute agitation in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(suppl 19):13–18.

86. Meehan, KM, Wang, H, David, SR, et al. Comparison of rapidly acting intramuscular olanzapine, lorazepam, and placebo: a double-blind, randomized study in acutely agitated patients with dementia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:494–504.

87. Wright, P, Birkett, M, David, SR, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of intramuscular olanzapine and intramuscular haloperidol in the treatment of acute agitation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1149–1151.

88. Meehan, K, Zhang, F, David, S, et al. A double-blind, randomized comparison of the efficacy and safety of intramuscular injections of olanzapine, lorazepam, or placebo in treating acutely agitated patients diagnosed with bipolar mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:389–397.

89. Spina, E, de Leon, J. Metabolic drug interactions with newer antipsychotics: a comparative review. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;100:4–22.

90. Reich, DL, Silvay, G. Ketamine: an update on the first twenty-five years of clinical experience. Can J Anaesth. 1989;36:186–197.

91. Roberts, DJ, Hall, RI, Kramer, AH, et al. Sedation for critically ill adults with severe traumatic brain injury: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2743–2751.

92. Bourgoin, A, Albanese, J, Wereszczynski, N, et al. Safety of sedation with ketamine in severe head injury patients: comparison with sufentanil. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:711–717.