Chapter 6 Pharmacogenetics

The Promise of Personalized Medicine

Take the example of a new anticancer drug, considered to be a breakthrough therapy for lung cancer. As a collection of diseases rooted in genetics, cancer has become one of the clearest examples of the potential for pharmacogenomics in predicting pharmacodynamics of a given drug in a given patient, as outlined in the following example.

Take the example of a new anticancer drug, considered to be a breakthrough therapy for lung cancer. As a collection of diseases rooted in genetics, cancer has become one of the clearest examples of the potential for pharmacogenomics in predicting pharmacodynamics of a given drug in a given patient, as outlined in the following example. An anticancer drug may be considered successful if 10% to 20% of patients respond to it. From a clinician’s perspective and from the perspective of those 10% to 20% of patients, this is a success, but from a health economist’s perspective, a $30,000-per-year drug that fails in 80% to 90% of patients is not cost-effective. If the annual cost for a new anticancer drug is going to be around $30,000 to $60,000, the only way to make these promising new drugs cost-effective is to administer them to only the 10% to 20% of patients who will benefit from them.

An anticancer drug may be considered successful if 10% to 20% of patients respond to it. From a clinician’s perspective and from the perspective of those 10% to 20% of patients, this is a success, but from a health economist’s perspective, a $30,000-per-year drug that fails in 80% to 90% of patients is not cost-effective. If the annual cost for a new anticancer drug is going to be around $30,000 to $60,000, the only way to make these promising new drugs cost-effective is to administer them to only the 10% to 20% of patients who will benefit from them.Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics

Pharmacogenomics takes a broader view of the influence of an individual’s entire genome on his or her response to drug therapy.

Pharmacogenomics takes a broader view of the influence of an individual’s entire genome on his or her response to drug therapy.One can consider pharmacogenetics to be the original term for this field, coined in the days when tools such as microarrays did not exist and the human genome had not been mapped. In those early days it seemed unlikely or impossible that an entire genome could be analyzed in an efficient enough manner to become a useful tool in everyday medicine. Now that we have the means and the knowledge to envision a genome-wide approach to everyday prescribing, the term pharmacogenomics is often used to refer to this field. Table 6-1 lists some of the terms commonly used in pharmacogenetics.

TABLE 6-1 Definitions of Some Common Terms Used in Pharmacogenetics

| Gene | A sequence of nucleotides that corresponds to a sequence of amino acids in an entire protein or part of a protein. Genes are typically found at a specific location on a chromosome. |

| Genome | The full genetic complement of an individual. |

| Allele | Any of the alternative forms of a gene at a particular locus. These alternative forms may or may not result in different phenotypes. |

| Null allele | A mutation in a gene that leads to a loss of function. Either the gene is not expressed at all (i.e., no protein or RNA) or the product is not functional. |

| Polymorphism | Variation in DNA sequence present at a specific locus within a population. |

| Genotype | The genetic makeup of an individual. |

| Phenotype | The observable physical or biochemical characteristics of an organism. Determined by genotype and environment. |

| Monogenic | Related to or controlled by a single gene |

| Polygenic | Related to or controlled by multiple genes. A polygenic trait is a phenotype that is determined by multiple genes rather than a single gene (monogenic). |

| Germ line | Cellular lineage; genetic information that is passed from one generation to the next. |

| Haplotype | A group of alleles of different genes on a single chromosome that are so closely linked that they are inherited as a unit. |

| Somatic cell | Any cell in the body, with the exception of those involved in reproduction. |

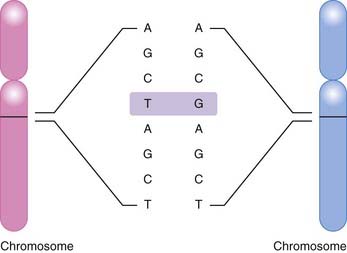

The most common basis for genetic variation, and thus the basis for a pharmacogenomic approach to drug therapy, is the single nucleotide polymorphism, or SNP (Figure 6-1). An SNP occurs when a single nucleotide is exchanged for another at a point in an individual’s genome. It is estimated that the human genome consists of approximately 3 billion nucleotides, which in specific combinations form 25,000 to 40,000 genes and encode approximately 100,000 proteins (at last count). SNPs that occur in coding regions of the genome have the potential to influence protein expression by altering an amino acid within the protein.

Nonsynonymous coding SNPs (cSNPs) or missense SNPs change the identity of an amino acid. Substitution of this amino acid may change the structure or function of the protein.

Nonsynonymous coding SNPs (cSNPs) or missense SNPs change the identity of an amino acid. Substitution of this amino acid may change the structure or function of the protein. Synonymous coding SNPs or sense SNPs do not change the identity of an amino acid and are not likely to affect the structure or function of the protein.

Synonymous coding SNPs or sense SNPs do not change the identity of an amino acid and are not likely to affect the structure or function of the protein.Pharmacokinetics

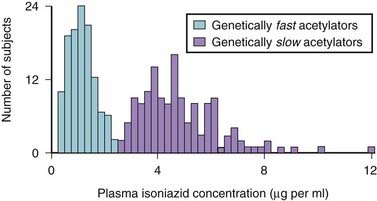

A classic example occurred with the antituberculosis drug isoniazid (Figure 6-2). Isoniazid is acetylated (metabolized) by N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2), and it was observed that some patients metabolized this drug slowly (i.e., were slow metabolizers), whereas others were rapid metabolizers.

A classic example occurred with the antituberculosis drug isoniazid (Figure 6-2). Isoniazid is acetylated (metabolized) by N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2), and it was observed that some patients metabolized this drug slowly (i.e., were slow metabolizers), whereas others were rapid metabolizers. The clinical consequence is that rapid metabolizers would have low plasma levels of the drug, increasing the potential for therapeutic failure, whereas slow metabolizers were predisposed to toxicities associated with the drug.

The clinical consequence is that rapid metabolizers would have low plasma levels of the drug, increasing the potential for therapeutic failure, whereas slow metabolizers were predisposed to toxicities associated with the drug. This wide variation in response to isoniazid led researchers to speculate that genetics might be playing a role. Isoniazid became one of the first drugs to be identified as having a genetic component to its pharmacologic actions.

This wide variation in response to isoniazid led researchers to speculate that genetics might be playing a role. Isoniazid became one of the first drugs to be identified as having a genetic component to its pharmacologic actions.

Figure 6-2 Influence of genetics on isoniazid metabolism.

(Modified from Meyer UA: Pharmacogenetics: five decades of therapeutic lessons from genetic diversity, Nat Rev Genet 2004 5:669, 2004. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers.)

Phase I Reactions, CYP450, and Genetic Polymorphisms

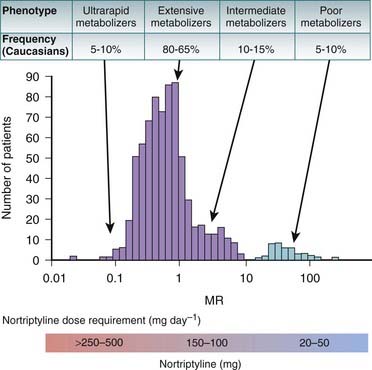

Figure 6-3 demonstrates how these phenotypes can influence the dosage of a drug, in this case the antidepressant nortriptyline. Note that most patients fall into the extensive or intermediate metabolizer category.

Figure 6-3 demonstrates how these phenotypes can influence the dosage of a drug, in this case the antidepressant nortriptyline. Note that most patients fall into the extensive or intermediate metabolizer category. It is the outliers, the poor metabolizers and the ultrarapid metabolizers, however, that require significant changes to the normal dose. Note that although there are fewer people with either of these phenotypes, poor metabolizers and ultrarapid metabolizers are still present in 10% to 20% of this population.

It is the outliers, the poor metabolizers and the ultrarapid metabolizers, however, that require significant changes to the normal dose. Note that although there are fewer people with either of these phenotypes, poor metabolizers and ultrarapid metabolizers are still present in 10% to 20% of this population.

Figure 6-3 Influence of phenotype on dosing.

(Modified from Meyer UA: Pharmacogenetics: five decades of therapeutic lessons from genetic diversity, Nat Rev Genet 2004 5:669, 2004. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers.)

CYP2D6

CYP2D6 is the CYP enzyme that is most associated with genetic polymorphisms. The frequency of polymorphisms varies greatly among ethnicities. For example, 5% to 10% of Caucasians are poor metabolizers, whereas only a small percentage (<1%) of Africans and Asians are poor metabolizers. Much of the phenotype in Caucasians is caused by the *4 null allele.

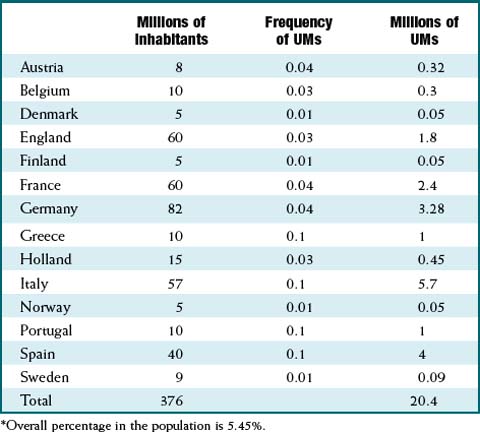

CYP2D6 is the CYP enzyme that is most associated with genetic polymorphisms. The frequency of polymorphisms varies greatly among ethnicities. For example, 5% to 10% of Caucasians are poor metabolizers, whereas only a small percentage (<1%) of Africans and Asians are poor metabolizers. Much of the phenotype in Caucasians is caused by the *4 null allele. Table 6-2 illustrates how much the frequency of CYP2D6 ultrarapid metabolizers can vary within Europe. For example, 10% of Greek citizens are ultrarapid metabolizers, whereas only 1% of people from Finland have this phenotype.

Table 6-2 illustrates how much the frequency of CYP2D6 ultrarapid metabolizers can vary within Europe. For example, 10% of Greek citizens are ultrarapid metabolizers, whereas only 1% of people from Finland have this phenotype. CYP2D6 is most commonly associated with metabolism of antidepressants, including the tricyclics (e.g., nortriptyline), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g., paroxetine), and venlafaxine. Other notable drugs using this isozyme include β-blockers (e.g., metoprolol) and antipsychotics (e.g., risperidone). Other examples include the following.

CYP2D6 is most commonly associated with metabolism of antidepressants, including the tricyclics (e.g., nortriptyline), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g., paroxetine), and venlafaxine. Other notable drugs using this isozyme include β-blockers (e.g., metoprolol) and antipsychotics (e.g., risperidone). Other examples include the following.

CYP3A4

CYP2C9

CYP2C9 is found on chromosome 10, close to CYP2C19 as well as 2C8 and 2C18. Several alleles have been implicated in abnormal metabolism, including *2 and *3, which are much more common in Caucasians (approximately 35%) compared with African and Asian ethnicities. These alleles are associated with impaired metabolism.

CYP2C9 is found on chromosome 10, close to CYP2C19 as well as 2C8 and 2C18. Several alleles have been implicated in abnormal metabolism, including *2 and *3, which are much more common in Caucasians (approximately 35%) compared with African and Asian ethnicities. These alleles are associated with impaired metabolism. This isozyme is responsible for metabolizing a number of drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes, most notably warfarin. Other substrates of note include a number of oral hypoglycemics (e.g., glyburide), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents (NSAIDs) (ibuprofen and several others), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective inhibitors, antiseizure medications (e.g., phenytoin), and angiotensin receptor blockers (e.g., losartan).

This isozyme is responsible for metabolizing a number of drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes, most notably warfarin. Other substrates of note include a number of oral hypoglycemics (e.g., glyburide), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents (NSAIDs) (ibuprofen and several others), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective inhibitors, antiseizure medications (e.g., phenytoin), and angiotensin receptor blockers (e.g., losartan).CYP2C19

The CYP2C19 isozyme has considerable genetic variation. The most common polymorphisms result in two null alleles, resulting in a phenotype of absent CYP2C19. This phenotype is most common in Asians (20%) and occurs in only 3% to 5% of Caucasians and Africans. The most common null alleles in Asians is *3 and in Caucasians is *2.

The CYP2C19 isozyme has considerable genetic variation. The most common polymorphisms result in two null alleles, resulting in a phenotype of absent CYP2C19. This phenotype is most common in Asians (20%) and occurs in only 3% to 5% of Caucasians and Africans. The most common null alleles in Asians is *3 and in Caucasians is *2.CYP1A2

There is wide variation among individuals in CYP1A2 expression and activity. These differences are also marked among different ethnicities, with lower activity found in Asians and Africans compared with Caucasians. As of 2009, 15 variants of CYP1A2 have been identified, and 158 SNPs have been found.

There is wide variation among individuals in CYP1A2 expression and activity. These differences are also marked among different ethnicities, with lower activity found in Asians and Africans compared with Caucasians. As of 2009, 15 variants of CYP1A2 have been identified, and 158 SNPs have been found. This isozyme plays a role in biotransformation of some of the most widely used substances, including nicotine and caffeine, and it is the study of the latter that led to this isozyme being one of the earliest studied for pharmacogenetic differences. Important drugs metabolized by CYP1A2 include the antipsychotics olanzapine and clozapine, the cardiovascular drugs propranolol and verapamil, and acetaminophen. Genotypes conferring both enhanced and reduced metabolism of clozapine have been identified.

This isozyme plays a role in biotransformation of some of the most widely used substances, including nicotine and caffeine, and it is the study of the latter that led to this isozyme being one of the earliest studied for pharmacogenetic differences. Important drugs metabolized by CYP1A2 include the antipsychotics olanzapine and clozapine, the cardiovascular drugs propranolol and verapamil, and acetaminophen. Genotypes conferring both enhanced and reduced metabolism of clozapine have been identified.Pharmacodynamics

Serotonin reuptake transporters in depression. Patients with polymorphisms that lead to reduced expression of serotonin transporters may be more resistant to treatment with SSRIs. The problem with trying to draw a definitive link between this phenotype and treatment failure is the influence of other factors such as psychotherapy and even other genetic factors that may predispose the patient to treatment-resistant depression.

Serotonin reuptake transporters in depression. Patients with polymorphisms that lead to reduced expression of serotonin transporters may be more resistant to treatment with SSRIs. The problem with trying to draw a definitive link between this phenotype and treatment failure is the influence of other factors such as psychotherapy and even other genetic factors that may predispose the patient to treatment-resistant depression. β2 receptors in asthma. Polymorphisms in β2 receptors can lead to either reduced or enhanced efficacy of β2 agonists. One study found that children with a specific polymorphism leading to more rapid response had shorter stays in the ICU after an asthma attack.

β2 receptors in asthma. Polymorphisms in β2 receptors can lead to either reduced or enhanced efficacy of β2 agonists. One study found that children with a specific polymorphism leading to more rapid response had shorter stays in the ICU after an asthma attack. One recent success story occurred with a drug called gefitinib, for advanced non–small cell lung cancer. The response rate, measured by a significant reduction in tumor size, was only 10% in this difficult-to-treat population. However, it was also observed that women of Asian descent with no history of smoking responded particularly well to this drug.

One recent success story occurred with a drug called gefitinib, for advanced non–small cell lung cancer. The response rate, measured by a significant reduction in tumor size, was only 10% in this difficult-to-treat population. However, it was also observed that women of Asian descent with no history of smoking responded particularly well to this drug. Eventually it was discovered that patients whose tumors had mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), the target for gefitinib, responded to the drug with remarkable predictability, whereas patients who lacked these mutations rarely if ever responded to treatment.

Eventually it was discovered that patients whose tumors had mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), the target for gefitinib, responded to the drug with remarkable predictability, whereas patients who lacked these mutations rarely if ever responded to treatment. CML is an ideal disease for personalized medicine, as it is caused by a single oncogene, known as BCR-ABL. BCR-ABL has a very specific marker that is part of the diagnostic process, and results in a gain of function (i.e., excess cell division).

CML is an ideal disease for personalized medicine, as it is caused by a single oncogene, known as BCR-ABL. BCR-ABL has a very specific marker that is part of the diagnostic process, and results in a gain of function (i.e., excess cell division).The Next Step: from Genetics to Genomics

For example, warfarin levels are influenced by alterations in CYP450 expression, as described earlier, but another key polymorphism that influences warfarin response occurs in the enzyme vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR), which is the pharmacodynamic target for warfarin.

For example, warfarin levels are influenced by alterations in CYP450 expression, as described earlier, but another key polymorphism that influences warfarin response occurs in the enzyme vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR), which is the pharmacodynamic target for warfarin. VKOR converts vitamin K to its reduced form, which is the form that activates several clotting factors in the coagulation cascade. Warfarin inhibits this enzyme, therefore inhibiting activation of clotting factors and inhibiting coagulation.

VKOR converts vitamin K to its reduced form, which is the form that activates several clotting factors in the coagulation cascade. Warfarin inhibits this enzyme, therefore inhibiting activation of clotting factors and inhibiting coagulation. Depending on the VKOR phenotype of the patient, he or she may require either higher or lower doses of warfarin. Patients with low VKOR levels require lower doses, and patients with high VKOR expression need higher-than-average doses. This polymorphism is actually thought to have a greater role in determining variations in warfarin dosage than polymorphisms in CYP450.

Depending on the VKOR phenotype of the patient, he or she may require either higher or lower doses of warfarin. Patients with low VKOR levels require lower doses, and patients with high VKOR expression need higher-than-average doses. This polymorphism is actually thought to have a greater role in determining variations in warfarin dosage than polymorphisms in CYP450. Complications in determining clinical impact therefore arise when a patient has both the CYP450 and VKOR polymorphisms, particularly when they occur in opposing directions: one leading to an increased dose requirement, and one to a decreased requirement. In these cases, it would be difficult to predict whether there is no net effect (i.e., the two cancel each other out) or the net direction of effect.

Complications in determining clinical impact therefore arise when a patient has both the CYP450 and VKOR polymorphisms, particularly when they occur in opposing directions: one leading to an increased dose requirement, and one to a decreased requirement. In these cases, it would be difficult to predict whether there is no net effect (i.e., the two cancel each other out) or the net direction of effect.Detection of Genetic Polymorphisms

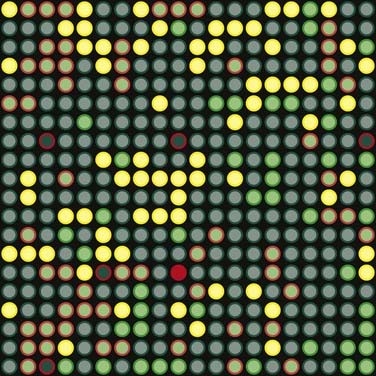

A microarray is a collection of immobilized single-stranded DNA fragments that contain a known nucleotide sequence that is used to identify and sequence DNA samples (Figure 6-4). Microarrays can be used in the analysis of gene expression. A microarray provides an automated means for identifying genes in a given sample. For example, cancerous and healthy cells may be analyzed from a single patient in order to determine the differences in gene expression between these two types of cells.

cDNA copies of the mRNA are made, and the cDNA is labeled with a fluorescent dye, one color (green) for one type of tissue, and another color (red) for the other tissue.

cDNA copies of the mRNA are made, and the cDNA is labeled with a fluorescent dye, one color (green) for one type of tissue, and another color (red) for the other tissue. Microarrays contain thousands of wells, each containing many identical copies of the same gene. Each well contains a different gene. The computer has a “map” of the microarray and knows which gene is contained in each well.

Microarrays contain thousands of wells, each containing many identical copies of the same gene. Each well contains a different gene. The computer has a “map” of the microarray and knows which gene is contained in each well. The cDNA is then pipetted onto each well and hybridizes with its complementary DNA strands in the microarray. The cDNA from the samples that do not bind is washed away.

The cDNA is then pipetted onto each well and hybridizes with its complementary DNA strands in the microarray. The cDNA from the samples that do not bind is washed away. The microarray is then placed into a scanner that identifies where each of the red and green samples have bound. In wells that have bound both samples, the color changes to yellow.

The microarray is then placed into a scanner that identifies where each of the red and green samples have bound. In wells that have bound both samples, the color changes to yellow. Therefore an expression pattern can be determined, in which certain genes are expressed only in cancerous tissue whereas other genes are not expressed in cancerous tissue but are expressed in normal tissue. This information can then be used to identify genes that can be selectively targeted with drug therapy.

Therefore an expression pattern can be determined, in which certain genes are expressed only in cancerous tissue whereas other genes are not expressed in cancerous tissue but are expressed in normal tissue. This information can then be used to identify genes that can be selectively targeted with drug therapy.Limitations of Pharmacogenomics

Access to therapy. The ability to target new drug development to specific genes has lead to concerns over whether patients with unusual genotypes or phenotypes will be ignored in the process. Although this is a valid concern, a counterargument is that in the past, drugs that unintentionally targeted these rare genotypes likely did not make it to market, as they were unable to prove efficacy in a wide enough population.

Access to therapy. The ability to target new drug development to specific genes has lead to concerns over whether patients with unusual genotypes or phenotypes will be ignored in the process. Although this is a valid concern, a counterargument is that in the past, drugs that unintentionally targeted these rare genotypes likely did not make it to market, as they were unable to prove efficacy in a wide enough population. Complexity. The integration of pharmacogenetics as a regular aspect of the prescribing process will need information technology to make it feasible for busy clinicians. The advent of electronic medical records and electronic prescribing should facilitate this process, but there will be a significant knowledge gap between earlier generations and current clinicians who were trained in the genomics era.

Complexity. The integration of pharmacogenetics as a regular aspect of the prescribing process will need information technology to make it feasible for busy clinicians. The advent of electronic medical records and electronic prescribing should facilitate this process, but there will be a significant knowledge gap between earlier generations and current clinicians who were trained in the genomics era. Time and expense. Even with the aid of information systems, pharmacogenetics will add another step to the prescribing process. Testing is also expensive at present, with a single test using AmpliChip technology costing around U.S. $1000. The advantage, however, is that the results can be used for a lifetime.

Time and expense. Even with the aid of information systems, pharmacogenetics will add another step to the prescribing process. Testing is also expensive at present, with a single test using AmpliChip technology costing around U.S. $1000. The advantage, however, is that the results can be used for a lifetime.Resources for Pharmacogenetic Information

The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) funds a Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base, which is available at www.pharmgkb.org. The site offers pharmacogenetic data categorized by genes, pathways (e.g., renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system), SNPs, and drugs.