Patient Safety, Communication, and Recordkeeping

After reading this chapter you will be able to:

Describe how to apply good body mechanics and posture to moving patients.

Describe how to apply good body mechanics and posture to moving patients.

Describe how to ambulate a patient and the potential benefits of ambulation.

Describe how to ambulate a patient and the potential benefits of ambulation.

Write definitions of key terms associated with electricity, including voltage, current, and resistance.

Write definitions of key terms associated with electricity, including voltage, current, and resistance.

Identify the potential physiologic effects that electrical current can have on the body.

Identify the potential physiologic effects that electrical current can have on the body.

State how to reduce the risk of electrical shock to patients and yourself.

State how to reduce the risk of electrical shock to patients and yourself.

Identify key statistics related to the incidence and origin of hospital fires.

Identify key statistics related to the incidence and origin of hospital fires.

List the conditions needed for fire and how to minimize fire hazards.

List the conditions needed for fire and how to minimize fire hazards.

Identify impediments to care and risk in the direct patient environment.

Identify impediments to care and risk in the direct patient environment.

State how communication can affect patient care.

State how communication can affect patient care.

Describe the two patient identifier system.

Describe the two patient identifier system.

List the factors associated with the communication process.

List the factors associated with the communication process.

Describe how to improve your communication effectiveness.

Describe how to improve your communication effectiveness.

Describe how to recognize and help resolve interpersonal or organizational sources of conflict.

Describe how to recognize and help resolve interpersonal or organizational sources of conflict.

List the common components of a medical record.

List the common components of a medical record.

State the legal and practical obligations involved in recordkeeping.

State the legal and practical obligations involved in recordkeeping.

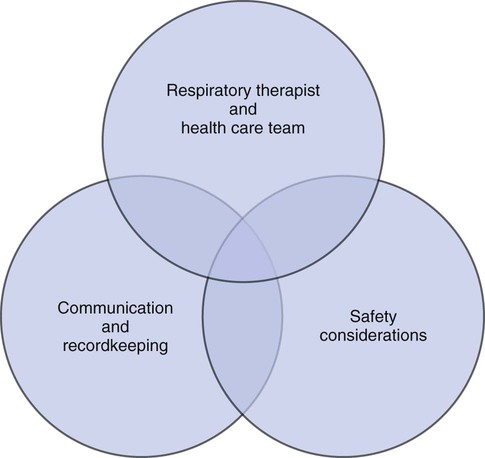

Respiratory therapists (RTs) share the general responsibilities for providing a safe and effective health care environment with nurses and other members of the health care team. The continuum of patient safety requires that the RT have specific technical knowledge of the environment of direct patient care. In addition to technical skills, all health care professionals must be able to communicate effectively with each other and with patients and patients’ families and to document pertinent information. Figure 3-1 shows this relationship for patient safety. This chapter provides the foundation knowledge needed to assume these general aspects of patient care effectively.

Safety Considerations

Patient Movement and Ambulation

Basic Body Mechanics

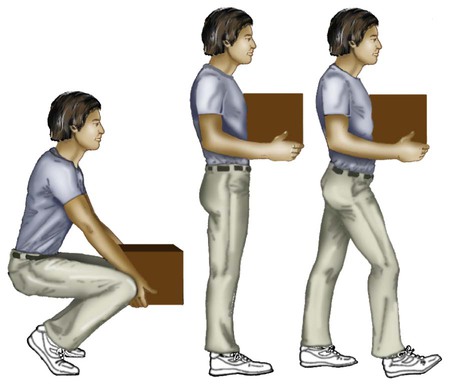

Posture involves the relationship of the body parts to each other. A person needs good posture to reduce the risk of injury when lifting patients or heavy equipment. Poor posture may place inappropriate stress on joints and related muscles and tendons. Figure 3-2 illustrates the correct body mechanics for lifting a heavy object. The correct technique calls for a straight spine and use of the leg muscles to lift the object.

Moving the Patient in Bed

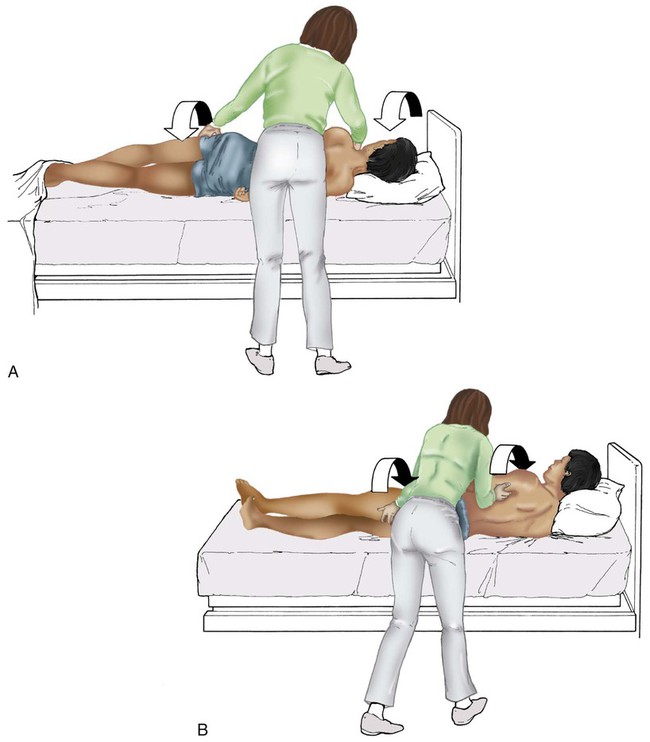

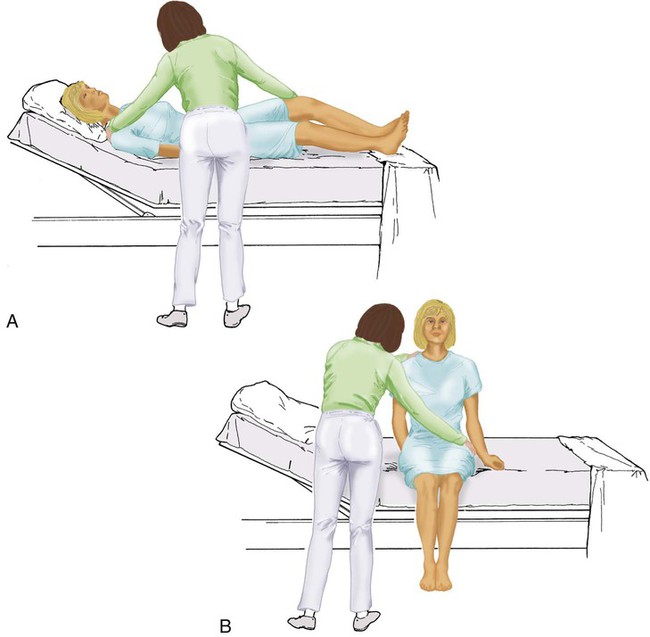

Figure 3-3 shows the correct technique for lateral movement of a bed-bound patient. Figure 3-4 illustrates the ideal method for moving a conscious patient toward the head of a bed. Figure 3-5 shows the proper technique for assisting a patient to the bedside position for dangling his or her legs or transfer to a chair.

Ambulation

Ambulation (walking) helps maintain normal body function. Extended bed rest can cause numerous problems, including bed sores and atelectasis (low lung volumes). Ambulation should begin as soon as the patient is physiologically stable and free of severe pain. Ambulation has been shown to reduce the length of hospital stay after surgery and in patients recovering from community-acquired pneumonia.1,2 Safe patient movement includes the following steps:

1. Place the bed in a low position and lock its wheels.

2. Place all equipment (e.g., intravenous [IV] equipment, nasogastric tube, surgical drainage tubes) close to the patient to prevent dislodgment during ambulation.

3. Move the patient toward the nearest side of bed.

4. Assist the patient to sit up in bed (i.e., arm under nearest shoulder and one under farthest armpit).

5. Place one hand under the patient’s farthest knee, and gradually rotate the patient so that his or her legs are dangling off the bed.

6. Let the patient remain in this position until dizziness or lightheadedness lessens (encouraging the patient to look forward rather than at the floor may help).

7. Assist the patient to a standing position.

8. Encourage the patient to breathe easily and unhurriedly during this initial change to a standing posture.

9. Walk with the patient using no, minimal, or moderate support (moderate support requires the assistance of two practitioners, one on each side of the patient).

10. Limit walking to 5 to 10 minutes for the first exercise.

Electrical Safety

Fundamentals of Electricity

< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mml" />

Because current is most important, you should be familiar with the equation used to calculate it:

Currents of 12 mA would cause a tingling sensation but no physical damage.

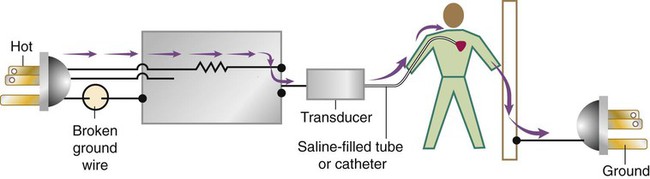

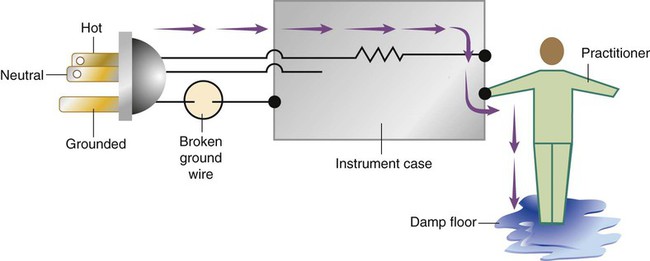

Figure 3-6 shows how current can flow through the body. In this case, a piece of electrical equipment is connected to AC line power via a standard three-prong plug. However, unknown to the practitioner, the cord has a broken ground wire. Normally, current leakage from the equipment would flow back to the ground through the ground wire. However, this pathway is unavailable. Instead, the leakage current finds a path of low resistance through the practitioner to the damp floor (an ideal ground).

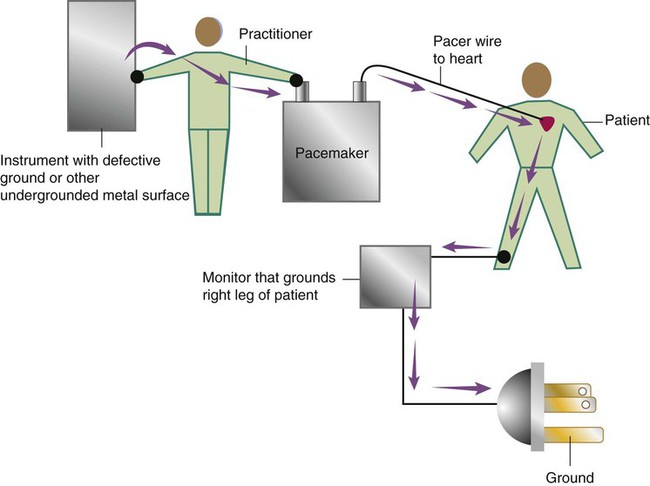

Current can readily flow into the body, causing damage to vital organs when the skin is bypassed via conductors such as pacemaker wires or saline-filled intravascular catheters (Figures 3-7 and 3-8). Even urinary catheters can provide a path for current flow. The heart is particularly sensitive to electrical shock. Ventricular fibrillation can occur when currents of 20 µA (20 microamperes, or 20 millionths of 1 ampere) are applied directly to the heart.

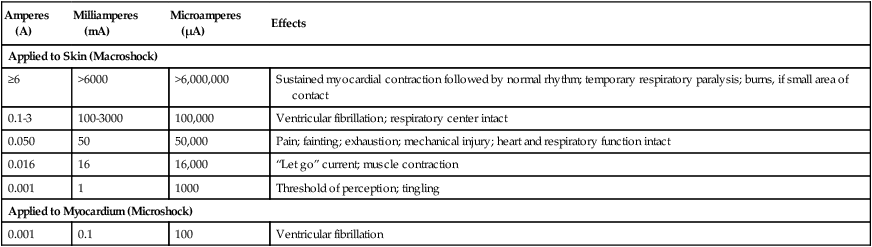

Electrical shocks are classified into two types: macroshock and microshock. A macroshock exists when a high current (usually >1 mA) is applied externally to the skin. A microshock exists when a small, usually imperceptible current (<1 mA) bypasses the skin and follows a direct, low-resistance path into the body. Patients susceptible to microshock hazards are termed electrically sensitive or electrically susceptible. Table 3-1 summarizes the different effects of these two types of electrical shock.

TABLE 3-1

| Amperes (A) | Milliamperes (mA) | Microamperes (µA) | Effects |

| Applied to Skin (Macroshock) | |||

| ≥6 | >6000 | >6,000,000 | Sustained myocardial contraction followed by normal rhythm; temporary respiratory paralysis; burns, if small area of contact |

| 0.1-3 | 100-3000 | 100,000 | Ventricular fibrillation; respiratory center intact |

| 0.050 | 50 | 50,000 | Pain; fainting; exhaustion; mechanical injury; heart and respiratory function intact |

| 0.016 | 16 | 16,000 | “Let go” current; muscle contraction |

| 0.001 | 1 | 1000 | Threshold of perception; tingling |

| Applied to Myocardium (Microshock) | |||

| 0.001 | 0.1 | 100 | Ventricular fibrillation |

*Physiologic effects of AC shocks applied for 1 second to the trunk or directly to the myocardium.

Fire Hazards

In 1980, approximately 13,000 health care facility fires were officially reported in the United States.3 During the period 2004-2006, the average annual number of fires in health care facilities was 6400.4 This significant reduction in health care facility fires is primarily due to education and enforcement of strict fire codes.

About 23% of fires in health care facilities occur in hospitals, and 44% occur in nursing homes; the most common site of origin of the fire is the kitchen.3 About 15% of hospital fires start in patient care rooms and are usually due to patients or visitors smoking or using open flames to light tobacco products. Medical facility fires cause an annual average of five civilian deaths and approximately $34 million in damage.4

Pull the pin—there may be an inspection tag attached

Aim the nozzle—aim low at the bottom of the fire

Squeeze the handle—the extinguisher has less than 30 seconds of spray time

The core fire plan follows the acronym RACE:

Rescue patients in the immediate area of the fire. The person discovering the fire should perform the rescue.

Alert other personnel about the fire so that they can assist in the rescue and can relay the location of the fire to officials. This step also involves pulling the fire alarm.

Contain the fire. After rescuing patients, shut doors to prevent the spread of the fire and the smoke. In patient care areas, follow your hospital policy regarding turning off oxygen zone valves.

Evacuate other patients and personnel in the areas around the fire who may be in danger if the fire spreads.

General Safety Concerns

In addition to electrical and fire safety, RTs need to be aware of general safety concerns, including the direct patient environment, disaster preparedness, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) safety, and medical gas safety. Medical gas safety is discussed in more detail in Chapter 37.

Medical Gas Cylinders

Storage of medical grade gases is regulated by National Fire Protection Association Standards 99 Health Care Facilities (2005 edition) and monitored by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Quantities of oxygen or nitrous oxide of 300 cubic feet or less (about 12 E-cylinders) in a patient care area not to exceed 2100 m2 are required to be secured properly but do not have special storage room requirements.5 Storing 300 to 3000 cubic feet of oxygen or nitrous oxide requires noncombustible or limited combustible storage rooms with self-closing doors and at least a  hour fire rating.5 Cylinders must be stored 20 feet from any combustibles (5 feet if room is equipped with a sprinkler system).5 Follow your hospital policies and procedures when handling, transporting, or storing medical gas cylinders.

hour fire rating.5 Cylinders must be stored 20 feet from any combustibles (5 feet if room is equipped with a sprinkler system).5 Follow your hospital policies and procedures when handling, transporting, or storing medical gas cylinders.

Communication

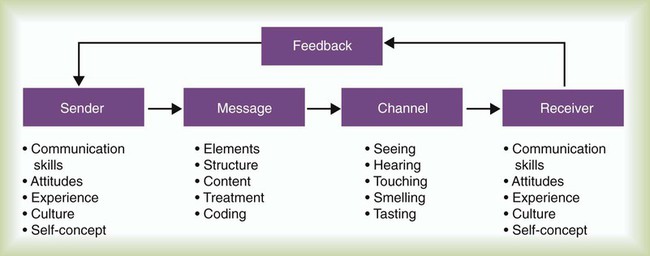

Communication is a dynamic human process involving sharing of information, meanings, and rules. Communication has five basic components: sender, message, channel, receiver, and feedback (Figure 3-9).

Communication in Health Care

Effective communication is the most important aspect of providing safe patient care. The first two 2010 National Patient Safety Goals of The Joint Commission are to improve accuracy of patient identification and to improve effectiveness of communicating critical test values among caregivers.6 All health care personnel must correctly identify patients before initiating care using a two patient identifier system. The patient identifiers can include any two of the following: name, birth date, and medical record number. Effectively communicating critical test values should include a “read back” scenario verifying the reporter and the receiver of the information and accurate reporting and recording of test values. Each institution may have specific values as critical test values; for example, RTs may be expected to report blood gas values of a pH less than 7.2 or a PO2 less than 50 mm Hg. The process of the “read back” scenario is described in Box 3-1.

Factors Affecting Communication

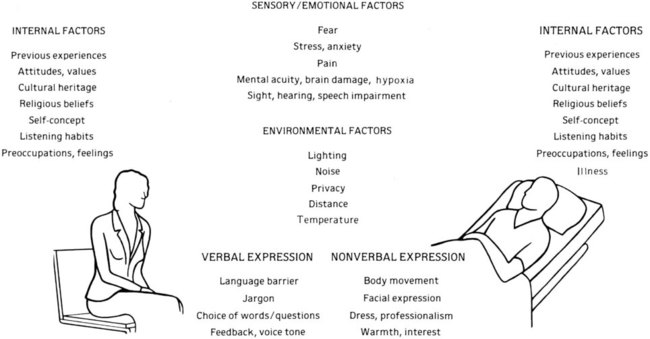

Many factors affect communication in the health care setting (Figure 3-10). The uniquely human or “internal” qualities of sender and receiver (including their prior experiences, attitudes, values, cultural backgrounds, and self-concepts and feelings) play a large role in the communication process.

Effective Communication in Health Care

RTs must be effective communicators. Effective communication occurs when the intent or purpose of the interaction is achieved. Several key purposes of communication are summarized in Box 3-2. The RT must consider the roles involved, the message, the channel, and the appropriate feedback to help achieve these purposes when communicating.

Improving Communication Skills

Practitioner as Sender

• Share information rather than telling. Health professionals often provide information in an authoritative manner by telling colleagues or patients what to do or say. This approach can cause defensiveness and lead to uncooperative behavior. Conversely, sharing information creates an atmosphere of cooperation and trust.

• Seek to relate to people rather than control them. This is of particular significance during communication with patients. Health care professionals often attempt to control patients. Few people like to be controlled. Patients feel much more important if they are treated as an equal partner in the relationship. Explaining procedures to patients and asking their permission to proceed is a way to make them feel a part of the decision making regarding their care.

• Value disagreement as much as agreement. When individuals express disagreement, make an attempt to understand what they are saying and do not become defensive. Be prepared for disagreement and be open to the input of others.

• Use effective nonverbal communication techniques. The nonverbal communication that you use is just as important as what you say. Nonverbal techniques include good eye contact, effective gesturing, facial expressions, and voice tone. It is important that your nonverbal communication matches what you are saying. If you are trying to establish rapport with a patient but do not look him or her in the eye, your communication will not be as effective. Your eye contact and facial expressions help convey what you are trying to say and cause your words to have more impact. Appropriate eye contact also conveys to the patient that you are a professional who is self-confident.

Practitioner as Receiver and Listener

• Work at listening. Listening is often a difficult process. It takes effort to hear what others are saying. Focus your attention on the speaker and on the message.

• Stop talking. Practice silent listening and avoid interrupting the speaker during an interaction. Interrupting the patient is a sure way to diminish effective communication.

• Resist distractions. It is easy to be distracted by surrounding noises and conversations. This is particularly true in a busy environment such as a hospital. When you are listening, try to tune out other distractions and give your full attention to the person who is speaking.

• Keep your mind open; be objective. Being open-minded is often difficult. All people have their own opinions that may influence what they hear. Try to be objective in your listening so that you treat everyone fairly.

• Hear the speaker out before making an evaluation. Do not just listen to the first few words of the speaker. This is a common mistake made by listeners. Often, listeners hear the first sentence and tune out the rest, assuming that they know what is being said. It is important to listen to the entire message; otherwise, you may miss important information.

• Maintain composure; control emotions. Allowing emotions, such as anger or anxiety, to distort your understanding or drawing conclusions before a speaker completes his or her thoughts or arguments is a common error in listening.

Providing Feedback

• Attending. Attending involves the use of gestures and posture that communicates one’s attentiveness. Attending also involves confirming remarks, such as, “I see what you mean.”

• Paraphrasing. Paraphrasing, or repeating the other’s response in one’s own words, is a technique useful in confirming that understanding is occurring between the parties involved in the interaction. However, overuse of paraphrasing can be irritating.

• Requesting clarification. Requesting clarification begins with an admission of misunderstanding on the part of the listener, with the intent being to understand the message better through restating or using alternative examples or illustrations. Overuse of this technique, as with paraphrasing, can hamper effective communication, especially if it is used in a condescending or patronizing manner. Requests for clarification should be used only when truly necessary and should always be nonjudgmental in nature.

• Perception checking. Perception checking involves confirming or disproving the more subtle components of a communication interaction, such as messages that are implied but not stated. For example, the RT might sense that a patient is unsure of the need for a treatment. In this case, the RT might check this perception by saying, “You don’t seem to be sure that you need this treatment. Is that correct?” By verifying or disproving this perception, both the health care professional and the patient understand each other better.

• Reflecting feelings. Reflecting feelings involves the use of statements to determine better the emotions of the other party. Nonjudgmental statements, such as, “You seem to be anxious about (this situation),” provide the opportunity for patients to express and reflect on their emotions and can help them confirm or deny their true feelings.

Minimizing Barriers to Communication

• Use of symbols or words that have different meanings. Words and symbols (including nonverbal communication) can mean different things to different people. These differences in meaning derive from differences in the background or culture between the sender and receiver and the context of the communication. For example, RTs often use the letters “COPD” to refer to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease caused by long-term smoking. Patients may hear “COPD” used in reference to them and be confused about the meaning and interpret COPD to mean a fatal lung disease. Never assume that the patient has the same understanding as you in the interpretation of commonly used symbols or phrases.

• Different value systems. Everyone has his or her own value system, and many people do not recognize the values held by others. A large difference between the values held by individuals can interfere with communication. A clinical supervisor may inform students of the penalties for being late with clinical assignments. If a student does not value timeliness, he or she may not take seriously what is being said.

• Emphasis on status. A hierarchy of positions and power exists in most health care organizations. If superiority is emphasized by individuals of higher status, communication can be stifled. Everyone has experienced interactions with professionals who make it clear who is in charge. Emphasis on status can be a barrier to communication not only among health care professionals but also between health care professionals and patients.

• Conflict of interest. Many people are affected by decisions made in health care organizations. If people are afraid that a decision will take away their advantage or invade their territory, they may try to block communication. An example might be a staff member who is unwilling to share expertise with students. This person may feel that a student is invading his or her territory.

• Lack of acceptance of differences in points of view, feelings, values, or purposes. Most of us are aware that people have different opinions, feelings, and values. These differences can thwart effective communication. To overcome this barrier, an effective communicator allows others to express their differences. Encouraging individuals to communicate their feelings and points of view benefits everyone. Most of us think we are always correct. Accepting input from others promotes growth and cooperation.

• Feelings of personal insecurity. It is difficult for people to admit feelings of inadequacy. Individuals who are insecure do not offer information for fear that they appear ignorant, or they may be defensive when criticized, blocking clear communication. Many of us have worked with individuals who are insecure, realizing the difficulty in communicating with them.

Recordkeeping

Components of a Traditional Medical Record

Each health care facility has its own specification for the medical records it keeps. Although the forms themselves vary among institutions, most acute care medical records share common sections (Box 3-3).

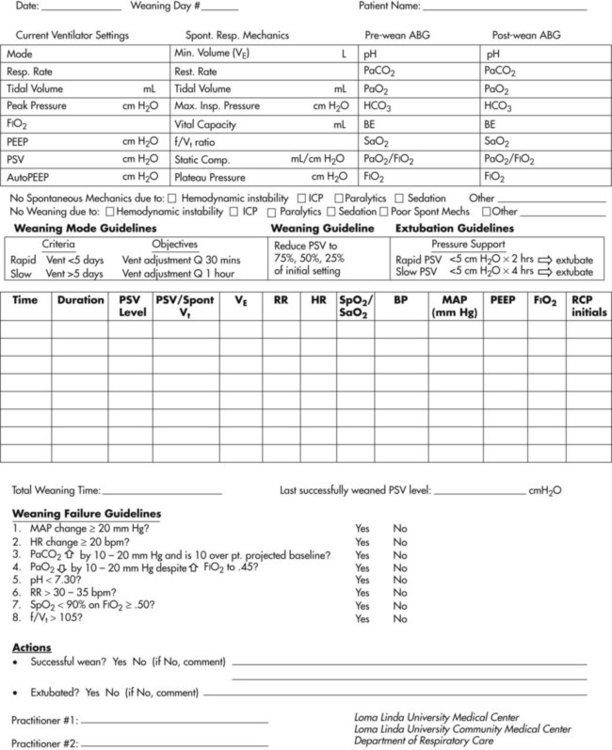

Figure 3-11 provides an example of a desaturation study for home oxygen therapy qualification. Documentation sheets are designed to report data briefly and to decrease time spent in documentation. Entries can include many measurements, and review of a sequence of entries can reveal trends in patient status.

Practical Aspects of Recordkeeping

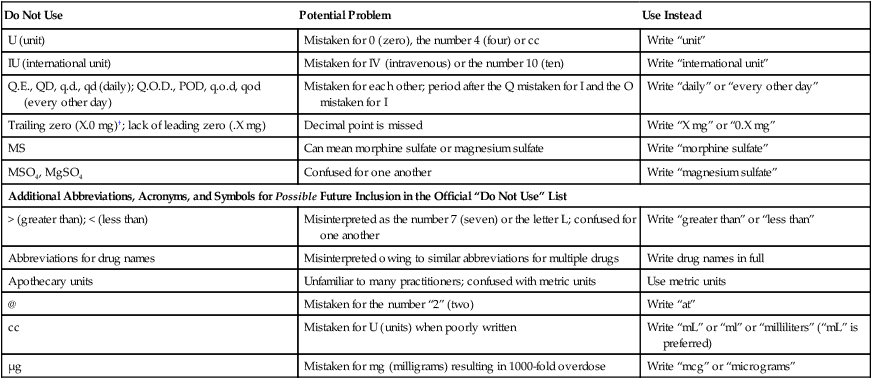

Recordkeeping is one of the most significant duties that a health care professional performs. Documentation is required for each medication, treatment, or procedure. Accounts of the patient’s condition and activities must be charted accurately and in clear terms. Brevity is essential, although a complete account of each patient encounter is needed. The use of standardized terms and abbreviations is acceptable; however, The Joint Commission has published a “Do Not Use” abbreviation list developed to reduce potential errors (Table 3-2).7 Documentation of consultations with the attending physician that include the date and time of the conversation is recommended.

TABLE 3-2

The Joint Commission “Do Not Use” List*

| Do Not Use | Potential Problem | Use Instead |

| U (unit) | Mistaken for 0 (zero), the number 4 (four) or cc | Write “unit” |

| IU (international unit) | Mistaken for IV (intravenous) or the number 10 (ten) | Write “international unit” |

| Q.E., QD, q.d., qd (daily); Q.O.D., POD, q.o.d, qod (every other day) | Mistaken for each other; period after the Q mistaken for I and the O mistaken for I | Write “daily” or “every other day” |

| Trailing zero (X.0 mg)†; lack of leading zero (.X mg) | Decimal point is missed | Write “X mg” or “0.X mg” |

| MS | Can mean morphine sulfate or magnesium sulfate | Write “morphine sulfate” |

| MSO4, MgSO4 | Confused for one another | Write “magnesium sulfate” |

| Additional Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Symbols for Possible Future Inclusion in the Official “Do Not Use” List | ||

| > (greater than); < (less than) | Misinterpreted as the number 7 (seven) or the letter L; confused for one another | Write “greater than” or “less than” |

| Abbreviations for drug names | Misinterpreted owing to similar abbreviations for multiple drugs | Write drug names in full |

| Apothecary units | Unfamiliar to many practitioners; confused with metric units | Use metric units |

| @ | Mistaken for the number “2” (two) | Write “at” |

| cc | Mistaken for U (units) when poorly written | Write “mL” or “ml” or “milliliters” (“mL” is preferred) |

| µg | Mistaken for mg (milligrams) resulting in 1000-fold overdose | Write “mcg” or “micrograms” |

*Applies to all orders and all medication-related documentation that is handwritten (including free-text computer entry) or on preprinted forms.

†Exception: A “trailing zero” may be used only where required to show the level of precision of the value being reported, such as for laboratory results, imaging studies that report size of lesions, or catheter/tube sizes. It may not be used in medication orders or other medication-related documentation.

From The Joint Commission: 2010 TJC “Do Not Use” list. http://www.jointcommission.org/ accessed December 17, 2010.

Accounts of care and the patient’s condition are generally printed by hand or handwritten. In some institutions, computerized patient information systems facilitate data entry by selection from menus of choices or direct typing. In either case, you must document only what is—not an interpretation or a judgment. Assessments of data must be clearly within one’s professional domain. When a practitioner cannot interpret the data obtained, he or she should state so in the record and contact another health care professional for advice or referral and document the referral in the patient’s medical record. Other general rules for medical recordkeeping are listed in Box 3-4. In addition to these general rules, each institution has its own policies governing medical recordkeeping.

Problem-Oriented Medical Record

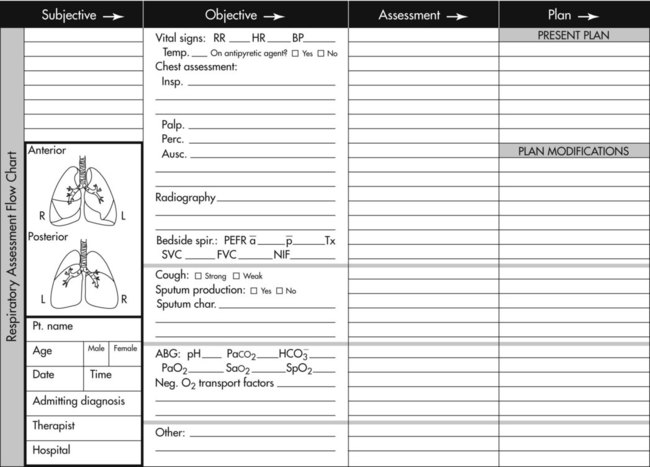

The POMR progress notes contain the findings (subjective and objective data), assessment, plans, and orders of the physicians, nurses, and other practitioners involved in the care of the patient. The format used is often referred to as SOAP (S = subjective information, O = objective information, A = assessment, P = plan of care). Figure 3-12 shows a representative SOAP form for respiratory care progress notes. Box 3-5 provides an example of a SOAP entry. Table 3-3 lists common objective data gathered by RTs and examples of applicable assessments and plans. In many institutions, all caregivers chart on the same form, using the SOAP format.

TABLE 3-3

Examples of Objective Data, Assessments, and Plans Typical for Documentation Using SOAP Notes

| Objective Data | Assessment | Plan |

| Sputum Production | ||

| Thick, purulent | Respiratory infection | Humidity therapy, antibiotics |

| Auscultation | ||

| Expiratory wheezing | Bronchospasm | Bronchodilator |

| Stridor | Upper airway obstruction | Racemic epinephrine, possible intubation |

| Late-inspiratory crackles | Atelectasis | Lung expansion therapy |

| Breathing Pattern | ||

| Prolonged expiratory time | Bronchospasm | Bronchodilators |

| Prolonged inspiratory time | Upper airway obstruction | Racemic epinephrine; consider need for intubation |

| Rapid and shallow | Restrictive lung disease | Notify physician, perform additional assessment, consider lung expansion therapy |

| Vital Signs | ||

| Acute tachycardia/tachypnea | Acute respiratory failure | Get ABGs, chest radiograph; call physician |

| Abnormal sensorium | Acute hypoxia | Assess patient further; oxygen therapy |

| ABGs | ||

| PaO2 40-60 mm Hg | Moderate hypoxemia | Give oxygen via cannula or mask |

| PaO2 < 40 mm Hg | Severe hypoxemia | Give high concentration oxygen as needed and consider positive pressure ventilation with PEEP or CPAP |

| Chest Radiograph | ||

| Low lung volumes or infiltrates | Atelectasis | Lung expansion therapy |

| Air in pleural space | Pneumothorax | Insert chest tube |