Paraneoplastic disorders

Spread of the neoplasm to the nervous system (see Chapter 46).

Spread of the neoplasm to the nervous system (see Chapter 46).

Systemic metabolic and hemodynamic disturbances (Table 47.1).

Systemic metabolic and hemodynamic disturbances (Table 47.1).

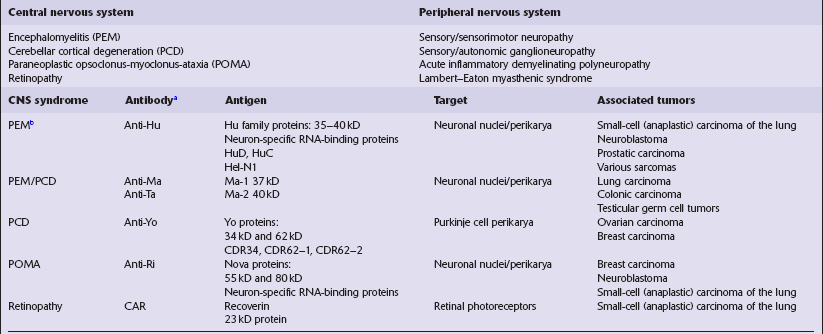

Table 47.1

Cancer-related systemic disorders producing CNS symptomatology

| Metabolic/endocrine disorders | Potential etiology |

| Hepatic failure | Liver metastases |

| Hypoglycemia | Consumption of glucose by disseminated sarcoma |

| Hyponatremia | Syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion |

| Hypercalcemia | Bone metastases/inappropriate parathyroid hormone production |

| Cushing syndrome | Inappropriate (ectopic) ACTH production |

| Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome | Thiamine deficiency secondary to emesis |

| Vascular disorders | Potential etiology |

| Encephalopathy/infarction–hyperviscosity | Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia |

| Infarction–hypercoagulability state | Mucin-secreting adenocarcinomas |

| Infarction | Polycythemia rubra vera |

| Embolic infarction | Marantic endocarditis |

| Hemorrhage | Reduced coagulation factors in hepatic failure |

| Thrombocytopenia in bone marrow failure |

Infections secondary to immunosuppression produced by lymphoreticular neoplasms (Table 47.2).

Infections secondary to immunosuppression produced by lymphoreticular neoplasms (Table 47.2).

Table 47.2

CNS infections particularly associated with lymphomas, leukemias, and myeloma

| Organism | Particular clinical association |

| Varicella zoster virus encephalitis | Hodgkin’s disease |

| Herpes simplex virus encephalitis | Hodgkin’s disease |

| Cytomegalovirus encephalitis | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (JC papovavirus) | Various |

| Listeria infection | Post-splenectomy |

| Streptococcal meningitis | Post-splenectomy |

| Toxoplasmosis | Lymphoma |

| Cryptococcal meningoencephalitis | Various |

| CNS aspergillosis | Various |

Side-effects of cancer therapy (Table 47.3).

Side-effects of cancer therapy (Table 47.3).

Table 47.3

CNS side-effects of cancer treatment

Radiotherapy

Encephalopathy

Delayed myelopathy

Hypothalamic/pituitary disturbances

Oncogenesis – mainly meningioma, sarcoma, glioma

Chemotherapy

Encephalopathy and/or myelopathy (particularly after BCNU, L-asparaginase, intrathecal methotrexate)

Cerebellar disorder (cytosine arabinoside)

Production of antibodies that simultaneously target onconeural antigens on neurons and neoplastic cells (Table 47.4), which is the subject of this chapter.

Production of antibodies that simultaneously target onconeural antigens on neurons and neoplastic cells (Table 47.4), which is the subject of this chapter.

Evidence for an autoimmune process is provided by the demonstration of:

an inflammatory process around targeted neurons.

an inflammatory process around targeted neurons.

onconeural antibodies directed against syndrome-specific neurons and neoplastic cells.

onconeural antibodies directed against syndrome-specific neurons and neoplastic cells.

onconeural antibodies present at higher titer in the cerebrospinal fluid than the serum.

onconeural antibodies present at higher titer in the cerebrospinal fluid than the serum.

PARANEOPLASTIC ENCEPHALOMYELITIS

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

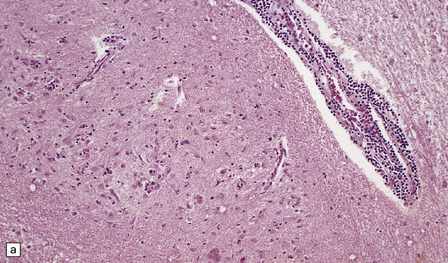

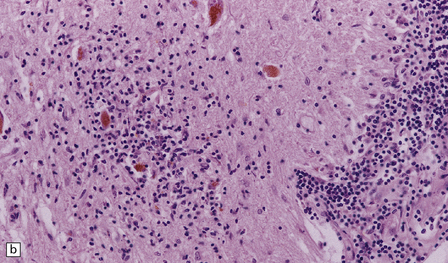

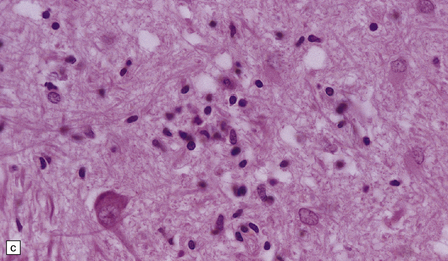

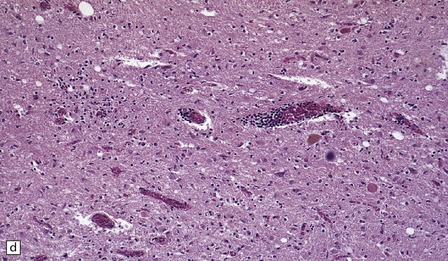

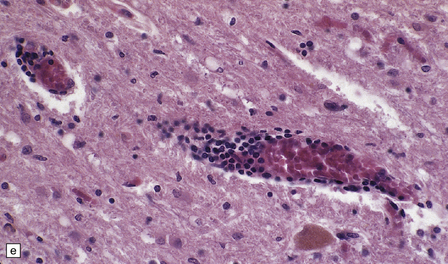

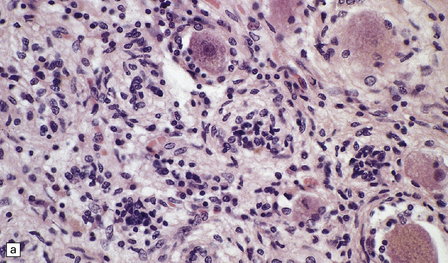

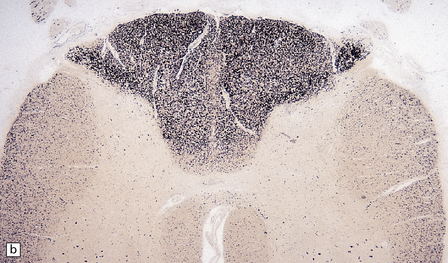

The histologic features of PEM are similar to those of viral encephalitis and myelitis. Neuronal loss, astrocytosis, and an increase in activated microglia are accompanied by an inflammatory infiltrate that consists mainly of lymphocytes and plasma cells and is concentrated in perivascular spaces (Fig. 47.1). The extent of the inflammation is variable and correlates poorly with neuronal loss. Inflammation affects gray matter, but secondary degeneration of white matter tracts can result. A leptomeningitis is nearly always present. No macroscopic abnormalities may be discerned.

47.1 Paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis.

(a,b,c) Perivascular lymphocytic cuffing, neuronophagia and gliosis are seen in the brain stem. (d) There is a diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate in the cervical cord. (e) Higher power view of perivascular lymphocytic cuffing, infiltration by microglia, and reactive astrocytosis.

Cerebral PEM is mainly confined to the medial temporal and inferior frontal structures, insular cortex, and cingulate gyrus (limbic encephalitis).

Cerebral PEM is mainly confined to the medial temporal and inferior frontal structures, insular cortex, and cingulate gyrus (limbic encephalitis).

The medulla is particularly affected in brain stem encephalitis.

The medulla is particularly affected in brain stem encephalitis.

Inflammation in the cerebellum is characteristically leptomeningeal or deep, affecting the dentate nucleus, but sparing the cortex. There is therefore only partial overlap with the histology of cerebellar cortical degeneration.

Inflammation in the cerebellum is characteristically leptomeningeal or deep, affecting the dentate nucleus, but sparing the cortex. There is therefore only partial overlap with the histology of cerebellar cortical degeneration.

Myelitis may involve the entire cord or only a few segments, generally in the cervical or lumbar regions (see Fig. 47.1).

Myelitis may involve the entire cord or only a few segments, generally in the cervical or lumbar regions (see Fig. 47.1).

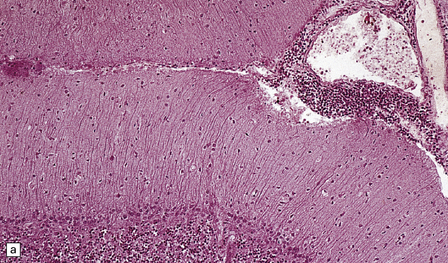

Some cases of PEM are combined with a sensory neuronopathy characterized by ganglionitis, loss of ganglion cells, and secondary degeneration of dorsal column fibers (Fig. 47.2).

47.2 Paraneoplastic ganglioneuronopathy.

(a) The dorsal root ganglion is infiltrated by lymphocytes and contains scattered nodules of Nageotte marking sites of ganglion cell degeneration. (b) A Marchi preparation reveals degeneration of dorsal column fibers in association with the sensory ganglioneuronopathy illustrated in (a).

PARANEOPLASTIC CEREBELLAR DEGENERATION (PCD)

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

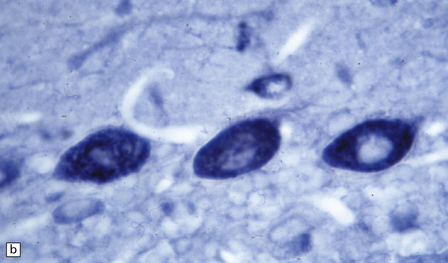

Mild cerebellar atrophy is occasionally observed, but there is generally no macroscopic abnormality in PCD. Histologically, a severe loss of Purkinje cells is evident throughout most of the cerebellar cortex, and is accompanied by variable loss of granule cells, activated microglia, and Bergmann gliosis (Fig. 47.3). An infiltrate of mononuclear leukocytes may be seen in the cortex, and there may be perivascular aggregates of lymphocytes and a leptomeningitis. However, inflammation may be sparse or absent, despite a severe loss of Purkinje cells. In a minority of cases of PCD, there is patchy loss of neurons accompanied by inflammation in other regions of the brain, indicating some overlap with PEM.

47.3 PCD.

(a) Purkinje cells are absent, the number of Bergmann astrocytes is increased, and there is isomorphic gliosis of the molecular layer. (b) Targeting of Purkinje cell perikarya by anti-Yo antibodies is demonstrated in the cerebellum of a patient with breast carcinoma. (Courtesy of Professor Scaravilli, Institute of Neurology, UK.)

REFERENCES

Carpentier, A.F., Delattre, J.Y. The Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol.. 2001;20:155–158.

Dalmau, J., Graus, F., Rosenblum, M.K., et al. Anti-Hu-associated paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis/sensory neuronopathy. A clinical study of 71 patients. Medicine (Baltimore).. 1992;71:59–72.

Dalmau, J., Gultekin, H.S., Posner, J.B., et al. Paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes: pathogenesis and physiopathology. Brain Pathol.. 1999;9:275–284.

Darnell, R.B., Posner, J.B. Paraneoplastic syndromes affecting the nervous system. Semin Oncol.. 2006;33:270–298.

Darnell, R.B., Posner, J.B. Autoimmune encephalopathy: the spectrum widens. Ann Neurol.. 2009;66:1–2.

Graus, F., Keime-Guibert, F., Reñe, R., et al. Anti-Hu-associated paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis: analysis of 200 patients. Brain.. 2001;124:1138–1148.

Henson R.A., Urich H., eds. Cancer and the nervous system. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1982.

McKeon, A., Pittock, S.J. Paraneoplastic encephalomyelopathies: pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol.. 2011;122:381–400.

Rosenfeld, M.R., Dalmau, J. Update on paraneoplastic and autoimmune disorders of the central nervous system. Semin Neurol.. 2010;30:320–331.