Chapter 59 Pancreatic cancer

Duodenal adenocarcinomas

Overview

The first case of duodenal adenocarcinoma was described by Hamburger in 1746 (Hamburger, 1775). In the United States, approximately 5000 patients are diagnosed with small bowel cancer every year, and 1000 of them have duodenal adenocarcinoma (Howe et al, 1999). Duodenal adenocarcinomas are rare tumors that account for approximately 0.3% of all gastrointestinal (GI) malignancies (Spira et al, 1977). Despite the duodenum representing only about 10% of the length of the small bowel, duodenal adenocarcinomas comprise 25% to 45% of small bowel tumors (Alwmark et al, 1980; Sohn et al, 1998); up to half occur near the ampulla of Vater, which explains why some studies group them with other periampullary cancers (Joesting et al, 1981). The incidence of small bowel cancers is estimated to be 1.4 per 100,000, with duodenal adenocarcinoma in approximately 0.17 per 100,000 (DiSario et al, 1994). Other malignant tumors such as carcinoid, gastrointestinal (GI) stromal tumor, lymphoma, and sarcoma can also occur in the duodenum but are far less common there than in the rest of the small intestine.

Presentation

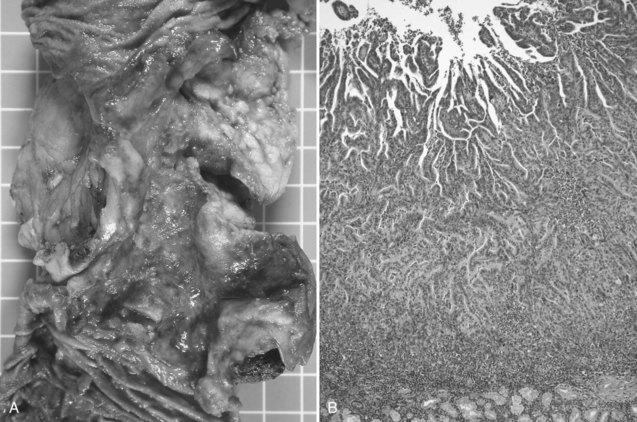

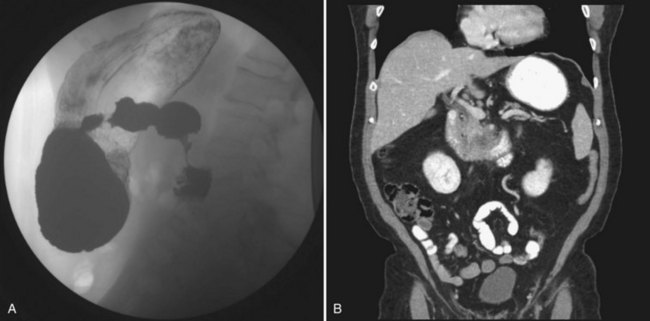

Duodenal adenocarcinoma has a slight male predominance. The median age at presentation is in the sixth and seventh decades of life (DiSario et al, 1994; Rose et al, 1996). Approximately half of the patients with duodenal adenocarcinoma are initially seen with symptoms of abdominal pain or gastric outlet obstruction: nausea, vomiting, early satiety, and anorexia. Duodenal cancers often present as circumferential napkin-ring type lesions (Fig. 59.1). However, patients can also be seen with bleeding, melena, or jaundice. Bauer and colleagues (1994) noted a 21% incidence of a palpable mass on physical exam. A small proportion of patients are asymptomatic; the lesion is identified during the workup of an unrelated medical problem or as a result of screening for familiar adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

Evaluation

The evaluation of any duodenal mass must assess for possible metastases and for resectability of the lesion (see Chapters 16 and 17). Depending on the patient’s presenting symptoms, the initial study that identifies the lesion will vary (see Fig. 59.1). Radiologic findings highly suggestive of malignancy include central necrosis or an intraluminal exophytic mass or intramural mass with ulceration (Fig. 59.2). Patients will need either a computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging to assess resectability and rule out metastatic disease. For the tumor to be considered potentially resectable, there should be no evidence of major vascular encasement, distant lymphadenopathy, or distant metastases (e.g., liver, peritoneum, lung). If patients undergo upper GI endoscopy, the lesion can be biopsied at that time. Additionally, if a segmental resection is being considered, an upper GI series is helpful, and the relationship of the tumor to the ampulla should be evaluated by endoscopy.

Risk Factors

The biology of duodenal adenocarcinoma is poorly understood. An adenoma-to-carcinoma sequence similar to that seen in colon cancer has been suggested. In various series of endoscopically resected adenomas, the incidence of malignancy varied from 10% to 42%, with villous adenomas being at higher risk for malignant transformation (Seifert et al, 1992; Witteman et al, 1993). Carcinoma in situ can be adequately treated with a local submucosal excision; however, it is generally impossible to know the maximal depth of invasion of the entire lesion before resection, and a more extensive procedure should be performed for any patient with invasive carcinoma (Bjork et al, 1990).

Patients with FAP are at significant risk for duodenal or ampullary adenomas, with an incidence as high as 88% (Church et al, 1992), and they have an increased relative risk of duodenal cancer of 330 compared with the general population (Offerhaus et al, 1992). Groves and colleagues (2002) prospectively followed 114 patients with FAP for 10 years, beginning at a median age of 42 years. Patients underwent upper endoscopy three times a year with a side-viewing duodenoscope. During this time three patients developed duodenal adenocarcinoma and three developed ampullary cancers. This occurred at a median of 6 years’ follow-up and at a median age of 68 years. All patients were classified according to the Spigelman classification: 3 were stage 0, 15 were stage I, 44 were stage II, 41 were stage III, and 11 were stage IV. Stage progression was seen in 0, 3, 7, 5, and 4 patients, respectively. Of the patients who developed invasive carcinoma, 4 were classified as Spigelman IV, but 2 were classified as Spigelman II and III, underscoring the need for surveillance in this population. Soravia and colleagues (1997) prospectively screened 74 patients over 5 years, during which time 11 patients (15%) developed advanced polyposis, and one patient developed duodenal cancer. The patient with adenocarcinoma presented at age 66 years, and the median age for duodenal polyposis for the group was 69 years (range, 38 to 66 years). All the patients in the study who underwent local resection of duodenal polyps developed recurrent polyps at sites of previous local resection. Duodenal and ampullary carcinomas are the second most common cause of death after colon cancer in patients with FAP, underscoring the need for aggressive surveillance.

Gardner syndrome is another condition associated with a high risk for duodenal adenocarcinoma. Patients present with GI polyposis, osteomas, and soft tissue tumors. The risk of malignant degeneration in duodenal polyps is between 3% and 12%, requiring these patients to also undergo an aggressive surveillance program (Sinha & Williamson, 1988). Patients with Peutz-Jehgers syndrome are also at risk, but it is lower than that seen in patients with Gardner syndrome or FAP.

The pathogenesis of duodenal adenocarcinoma is poorly understood. It appears to have a biology similar to, yet distinct from, colon cancer and other pancreatohepatobiliary tumors. Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes that appear to contribute to the malignant progression include KRAS, TP53, ERBB2, and TGFBRII (Achille et al, 1998; Younes et al, 1997; Zhu et al, 1996). In patients with FAP, the normal duodenal mucosa and duodenal polyps have a higher COX-2 expression than patients with sporadic duodenal adenomas (Brosens et al, 2005). This increased expression may explain the poorer response to inhibitory COX-2 chemoprevention in these lesions.

Therapy

Surgical

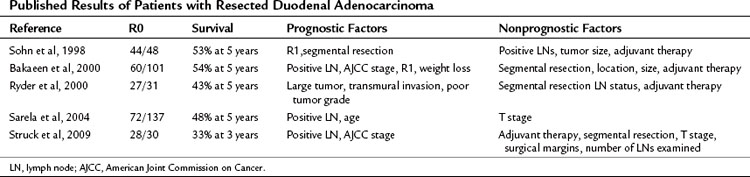

Surgical resection is the strongest predictor of long-term survival. Most series of resected duodenal carcinoma document a 5-year overall survival of more than 40%, which is twofold better than that of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (Table 59.1).

Debate is active and ongoing as to the role of segmental resection of the duodenum in patients with duodenal adenocarcinoma not involving the ampulla. This consideration is typically germane only to lesions in the distal aspect of the duodenum. A number of clinical series from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, and Duke University have shown no difference in survival between pancreaticoduodenectomy and a segmental resection (Cecchini et al, 2011; Rose et al, 1996). On the other hand, some series suggest that a more radical resection may improve overall survival (Alwmark et al, 1980; Dabaja et al, 2004). It is not unexpected that multiple small series of patients demonstrate no adverse effect of performing local en bloc resections for lesions in the third or fourth portions of the duodenum; because the lymphatic drainage to this area should be into the small bowel mesentery and not via the pancreatoduodenal lymphatic basins. Whether a pancreatoduodenectomy or a segmental resection is performed depends on the tumor’s location with respect to the ampulla and the ability to achieve a complete resection, which ultimately is the most important prognostic factor.

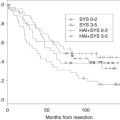

Unlike many other GI tumors, metastatic disease to regional lymph nodes is not a consistent predictor of poor outcome. In the series by Joesting and colleagues (1981) and Ouriel and Adams (1984), lymph nodes did not predict an adverse outcome. More recent series from MGH and the Mayo Clinic, on the other hand, have identified that lymph node involvement was associated with an adverse outcome (Cecchini et al, 2011; Bakaeen et al, 2000). In both series, overall survival decreased from 65% to 25% in the MGH series and from 68% to 22% in the Mayo Clinic series when lymph nodes were involved. The MSKCC group evaluated lymph node status in the setting of the number of nodes evaluated. Similar to gastric cancer, resection and assessment of more than 15 lymph nodes assessed improved the disease staging and the prognostic value of finding no lymph node metastases (Sarela et al, 2004). The modern series from MGH was the first to identify perineural invasion as the most powerful independent predictor of survival (Cecchini et al, 2011). The 5-year overall survival was 56% versus 19% for patients with and without perineural invasion, respectively.

Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Therapy

The role of neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy for duodenal adenocarcinoma has not been studied in a Phase III prospective randomized trial. Duodenal cancers were treated in the cohort of periampullary tumors in a European Phase III adjuvant trial without any evidence of improved survival. However, a high rate of chemotherapy and radiation therapy noncompliance was reported, and the duodenal cancers were not analyzed separately; therefore the results must be interpreted with caution. The largest retrospective review from the National Cancer Database documented that only 15% of patients received adjuvant radiation therapy, and 21% received chemotherapy (Howe et al, 1999). The study from Johns Hopkins included 14 node-positive patients who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy and adjuvant chemoradiation therapy who had improved local control and median survival, but no difference was reported in 5-year overall survival (Swartz et al, 2007). Therefore no conclusive decisions can be made based on the current data in the literature regarding the role of adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Patterns of Recurrence

The patterns of recurrence have not been well defined in duodenal adenocarcinoma. Approximately 17% to 44% of patients will be seen with locoregional recurrences, mainly in the operative bed and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. In the MGH series, the first site of recurrence was distant in 21%, locoregional in 19%, and both in 5% at a median follow-up of 14.5 months. In the MDACC series, 17% of patients had locoregional recurrences and 33% had distant recurrences (Barnes et al, 1994). In the series from Duke, 44% of patients were seen with locoregional recurrences (Kelsey et al, 2007).

Achille A, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of sporadic duodenal cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:760-765.

Alwmark A, Andersson A, Lasson A. Primary carcinoma of the duodenum. Ann Surg. 1980;191:13-18.

Bakaeen FG, et al. What prognostic factors are important in duodenal adenocarcinoma? Arch Surg. 2000;135:635-641. discussion 641-642

Barnes GJr, et al. Primary adenocarcinoma of the duodenum: management and survival in 67 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 1994;1:73-78.

Bauer RL, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the small intestine: 21-year review of diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 1994;1:183-188.

Bjork KJ, et al. Duodenal villous tumors. Arch Surg. 1990;125:961-965.

Brosens LA, et al. Increased cyclooxygenase-2 expression in duodenal compared with colonic tissues in familial adenomatous polyposis and relationship to the -765G -> C COX-2 polymorphism. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4090-4096.

Church JM, et al. Gastroduodenal polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:1170-1173.

Dabaja BS, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel: presentation, prognostic factors, and outcome of 217 patients. Cancer. 2004;101:518-526.

DiSario JA, et al. Small bowel cancer: epidemiological and clinical characteristics from a population-based registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:699-701.

Groves CJ, et al. Duodenal cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): results of a 10-year prospective study. Gut. 2002;50:636-641.

Hamburger G. Disputationes ad morborum historium et curationem facientes. Lausanne, Switzerland: MM Bousquet; 1775.

Howe JR, et al. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel: review of the National Cancer Data Base, 1985-1995. Cancer. 1999;86:2693-2706.

Joesting DR, et al. Improving survival in adenocarcinoma of the duodenum. Am J Surg. 1981;141:228-231.

Kelsey CR, et al. Duodenal adenocarcinoma: patterns of failure after resection and the role of chemoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1436-1441.

Offerhaus GJ, et al. The risk of upper gastrointestinal cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1980-1982.

Ouriel K, Adams JT. Adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. Am J Surg. 1984;147:66-71.

Rose DM, et al. Primary duodenal adenocarcinoma: a ten-year experience with 79 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:89-96.

Ryder NM, et al. Primary duodenal adenocarcinoma: a 40-year experience. Arch Surg. 2000;135:1070-1074.

Sarela AI, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the duodenum: importance of accurate lymph node staging and similarity in outcome to gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:380-386.

Seifert E, Schulte F, Stolte M. Adenoma and carcinoma of the duodenum and papilla of Vater: a clinicopathologic study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:37-42.

Sinha J, Williamson RC. Villous adenomas and carcinoma of the duodenum in Gardner’s syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1988;64:899-902.

Sohn TA, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the duodenum: factors influencing long-term survival. J Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2:79-87.

Soravia C, et al. Management of advanced duodenal polyposis in familial adenomatous polyposis. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:474-478.

Spira IA, Ghazi A, Wolff WI. Primary adenocarcinoma of the duodenum. Cancer. 1977;39:1721-1726.

Swartz MJ, et al. Adjuvant concurrent chemoradiation for node-positive adenocarcinoma of the duodenum. Arch Surg. 2007;142:285-288.

Witteman BJ, et al. Villous tumours of the duodenum: an analysis of the literature with emphasis on malignant transformation. Neth J Med. 1993;42:5-11.

Younes N, et al. The presence of K-12 ras mutations in duodenal adenocarcinomas and the absence of ras mutations in other small bowel adenocarcinomas and carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 1997;79:1804-1808.

Zhu L, et al. Adenocarcinoma of duodenum and ampulla of Vater: clinicopathology study and expression of p53, c-neu, TGF-alpha, CEA, and EMA. J Surg Oncol. 1996;61:100-105.