Chapter 87 Overview of Mortality and Morbidity

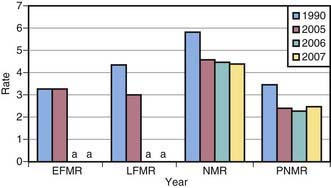

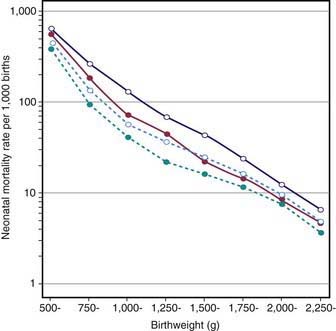

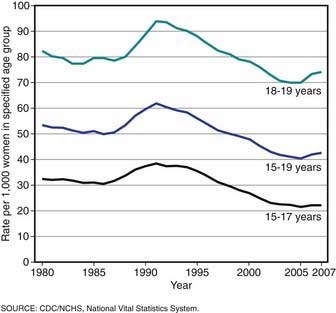

Perinatal mortality is influenced by prenatal, maternal, and fetal conditions and by circumstances surrounding delivery. Perinatal deaths are associated with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR); conditions that predispose the fetus to asphyxia, such as placental insufficiency; severe congenital malformations; and overwhelming early-onset neonatal infections (Table 87-1). The major causes of neonatal mortality are prematurity/low birthweight (LBW) and congenital anomalies. Mortality is highest during the 1st 24 hr after birth. Neonatal mortality (4.27/1,000 in 2008) accounts for about two thirds of all infant deaths (deaths before 1yr of age). Neonatal and postneonatal mortality rates in the USA have declined or remained stable (Fig. 87-1). Factors related to the decline in mortality include improved obstetric and neonatal intensive care management with a significant reduction in birthweight-specific neonatal mortality (Fig. 87-2). Further reduction in neonatal mortality will depend on prevention of preterm delivery and LBW, prenatal diagnosis and early management of congenital anomalies, and effective diagnosis and treatment of diseases that result from adverse factors during pregnancy, labor, and/or delivery (see Table 87-1). In the USA each year, approximately 6 million pregnancies, 4 million live births, 19,000 neonatal deaths, and 28,000 infant deaths occur. Ten per cent of births are to teenage women between the ages of 15 and 19 yr, a proportion that has been decreasing for about 35 yr (Fig. 87-3). Births to girls 10-14 yr, very young mothers who are at great social and medical risk, declined substantially over this period. The proportion of deaths to unmarried women was 40.6% in 2008, the highest ever in U.S. history.

Figure 87-3 Birthrates for teenagers by age, USA, final for 1980-2006 and preliminary for 2007.

(From Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ: Births: preliminary data for 2007, Natl Vital Stat Rep 57:12:1–23, 2009.)

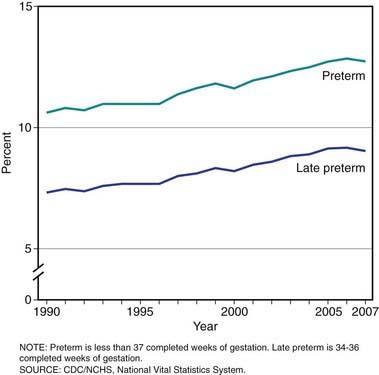

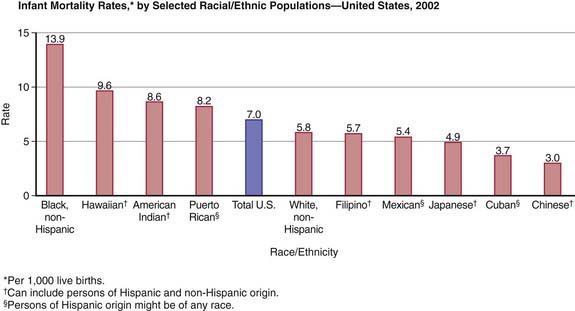

The LBW rate (infants weighing ≤ 2,500 g at birth each year) in the USA increased from 6.6% to 8.2% between 1981 and 2008, whereas the very low birthweight (VLBW) rate (infants weighing ≤1,500 g at birth) increased from 1.1% to 1.46% of all births. In the past decade, LBW has increased among white infants, mainly because of a rise in the number of multiple births (often associated with assisted reproduction) (Fig. 87-4). Nonetheless, LBW and VLBW rates remain highest among black infants. Reasons for the racial disparity in LBW remain unclear. Despite advances in prenatal and obstetric care, racial disparity in birthweight persists, thus suggesting the need for novel prevention programs. Furthermore, although preterm LBW survival is better among black neonates (see Fig. 87-2), overall neonatal and infant mortality rates remain highest among blacks (Fig. 87-5), even for infants born to extremely low-risk mothers (married, aged 20-34 yr, ≥13 yr of education, adequate prenatal care, no medical risk factors, no alcohol or tobacco use during pregnancy). A reduction in the racial disparity in mortality is an important public health issue reflected in Healthy People 2010, the U.S. national health objectives for the year 2010.

Figure 87-4 Preterm birthrates, USA, final for 1990-2006 and preliminary for 2007.

(From Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ: Births: preliminary data for 2007, Natl Vital Stat Rep 57:12:1–23, 2009.)

Figure 87-5 Infant mortality rates by race and ethnicity, 2002. In 2002, the infant mortality rate was highest for infants of non-Hispanic black mothers. Infants of Hawaiian, Native American, and Puerto Rican mothers also had high rates. The lowest rates were observed for infants of Cuban and Chinese mothers. Additional birth data are available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/births.htm.

(Adapted from Mathews TJ, Menacker F, MacDorman MF: Infant mortality statistics from the 2002 period linked birth/infant death data set. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr53/nvsr53_10.pdf. Accessed April 26, 2010.)

Although 99% of births occur in hospitals, only 80-85% of pregnant women receive ideal prenatal care in the 1st trimester. Many women who receive inadequate prenatal care are at risk for perinatal complications. Barriers to prenatal care include lack or insufficiency of money or insurance to pay for care; poor coordination of services, including language and cultural issues; and inadequate effective education about the importance of prenatal care. Successful and adequate provision of high-quality prenatal care requires competent health care professionals and coordination of services among physicians’ offices, clinics, community hospitals, specially regionalized programs for high-risk mothers and infants, and tertiary care centers. Regional perinatal programs should provide continuing education and consultation in both the community and the referral center and transportation for pregnant women and newborn infants to appropriate hospitals; they should also include a regional hospital with facilities, equipment, and personnel for obstetric and neonatal intensive care (Table 87-2).

Table 87-2 LEVELS OF IN-HOSPITAL PERINATAL CARE

| MATERNAL | NEONATE |

|---|---|

| BASIC | |

| Monitor and care for low-risk patients | Resuscitation |

| Stabilization | |

| Triage for high risk for transfer | Well neonatal care |

| Detection and care of unanticipated labor problems | Nursery care |

| Emergency cesarean delivery within 30 min | Visitation |

| General pediatrician staff (capable of neonatal resuscitation) | |

| Blood bank, anesthesia, radiology, ultrasound, and laboratory support | |

| Care of postpartum problems | |

| Obstetrician, nurse, midwife staff | |

| SPECIAL CARE | |

| Basic services plus: | Basic services plus: |

| Care of high-risk pregnancies | Care of high-risk neonate with short-term problems |

| Triage, transfer of high-risk pregnancies (<32 wk, intrauterine growth retardation, preeclampsia, severe maternal medical illness) | Stabilization before transfer (<1,500 g, <32 wk, critically ill) Accept convalescing back (reverse) transfers |

| SUBSPECIALTY CARE | |

| Basic plus specialty care plus: | Basic plus specialty care plus: |

| Experienced perinatologist (24-hr coverage) | Experienced neonatologist (24-hr coverage) |

| Evaluation of high-risk therapies | Inborn plus transferred patients |

| Care for severe maternal medical or obstetric illnesses | Evaluation of high-risk therapies |

| All pediatric medical, radiologic, and surgical subspecialties | |

| High-risk fetal care (Rh disease, nonimmune hydrops, life-threatening anomalies) | Neonatal intensive care unit with operating room capabilities High-risk follow-up |

| Outcomes research | Outcomes research |

| Community education | Community education |

From American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Guidelines for perinatal care, ed 5, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2002, American Academy of Pediatrics.

Postneonatal mortality refers to deaths between 28 days and 1yr of life. Historically, these infant deaths were due to causes outside the neonatal period, such as SIDS, infections (respiratory, enteric), and trauma. With the advent of modern neonatal care, many VLBW and preterm infants who would have died in the 1st mo of life now survive the neonatal period only to succumb to the sequelae listed in Table 87-3. This delayed neonatal mortality is an important contributor to postneonatal mortality and explains its lack of decline during the last years.

Table 87-3 MORBIDITIES AND SEQUELAE OF PERINATAL AND NEONATAL ILLNESS

| MORBIDITIES | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM | |

| Spastic diplegic-quadriplegic cerebral palsy | Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, periventricular leukomalacia, undetermined antenatal factors |

| Choreoathetotic cerebral palsy | Bilirubin encephalopathy (kernicterus) |

| Microcephaly | Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, intrauterine infection (rubella, CMV) |

| Communicating hydrocephalus | Intraventricular hemorrhage, meningitis |

| Seizures | Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, hypoglycemia |

| Encephalopathy | Congenital infections (rubella, CMV, HIV, toxoplasmosis) |

| Educational failure and/or mental retardation | Immaturity, hypoxia, hypoglycemia, cerebral palsy, intraventricular hemorrhage, low socioeconomic status |

| SENSATION—PERIPHERAL NERVES | |

| Reduced visual acuity (blindness) | Retinopathy of prematurity |

| Strabismus | Undetermined, prematurity |

| Hearing impairment (deafness) | Drug toxicity (furosemide, aminoglycosides), bilirubin encephalopathy, hypoxia ± hyperventilation |

| Poor speech | Immaturity, chronic illness, hypoxia, prolonged endotracheal intubation, hearing deficit |

| Paralysis-paresis | Birth trauma—brachial plexus, phrenic nerve, spinal cord |

| RESPIRATORY | |

| BPD | Oxygen toxicity, barotrauma |

| Subglottic stenosis | Endotracheal tube injury |

| Sudden infant death syndrome | Prematurity, BPD, infant of illicit drug user |

| Choanal stenosis, nasal septum destruction | Nasotracheal intubation |

| Growth failure | |

| CARDIOVASCULAR | |

| Cyanosis | Precorrective palliative care of congenital cyanotic heart disease, cor pulmonale from BPD, reactive airway |

| Heart failure | Precorrective palliative care of complex congenital heart disease, BPD, ventricular septal defect |

| GASTROINTESTINAL | |

| Short-gut syndrome | Necrotizing enterocolitis, gastroschisis, malrotation-volvulus, cystic fibrosis, intestinal atresia |

| Cholestatic liver disease (cirrhosis, hepatic failure) | Hyperalimentation toxicity, sepsis, short-gut syndrome |

| Failure to thrive | Short-gut syndrome, cholestasis, BPD, cerebral palsy, severe congenital heart disease |

| Inguinal hernia | Unknown |

| MISCELLANEOUS | |

| Cutaneous scars | Chest tube or intravenous catheter placement, hyperalimentation, subcutaneous infiltration, fetal puncture, intrauterine varicella, cutis aplasia |

| Absence of radial artery pulse | Frequent arterial puncture |

| Hypertension | Renal thrombi, repair of coarctation of aorta |

BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; CMV, cytomegalovirus.

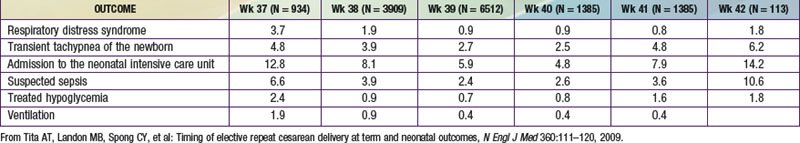

Late preterm infants are at risk for hypothermia, hypoglycemia, respiratory distress, apnea, jaundice, feeding difficulties, dehydration, and suspected sepsis. They are also at risk of having rehospitalizations. Even term infants born at 37 and 38 wk by cesarean section are at increased risk for respiratory distress syndrome, transient tachypnea of the newborn, suspected sepsis, hypoglycemia, need for ventilatory support, and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (Table 87-4).

Table 87-4 INCIDENCE OF ADVERSE OUTCOME ACCORDING TO COMPLETED WEEK OF GESTATION AT DELIVERY FOR INFANTS BORN BY CAESAREAN SECTION

Alexander GR, Wingate MS, Bader D, et al. The increasing racial disparity in infant mortality rates: composition and contributors to recent US trends. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:51.e1-51.e9.

Ambalavanan N, Baibergenova A, Carlo WA, et al. Early prediction of poor outcome in extremely low birth weight infants by classification tree analysis. Trial of Indomethacin Prophylaxis in Preterms (TPIPP) Investigators. J Pediatr. 2006;148:438-444.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Policy statement—hospital stay for healthy term newborns. Pediatrics. 2010;125:405-409.

Baker LC, Afendulis CC, Chandra A, et al. Differences in neonatal mortality among whites and Asian American subgroups. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:69-76.

Bhandari V, Bizzarro MJ, Shetty A, et al. Familial and genetic susceptibility to major neonatal morbidities in preterm twins. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1901-1906.

Bruckner TA, Saxton KB, Anderson E, et al. From paradox to disparity: trends in neonatal death in very low birth weight non-Hispanic black and white infants, 1989–2004. J Pediatr. 2009;155:482-487.

Bukowski R, Malone FD, Porter FT, et al. Preconceptional folate supplementation and the risk of spontaneous preterm birth: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000061.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Apparent disappearance of the black-white infant mortality gap—Dane County, Wisconsin, 1990–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:561-565.

de Jonge A, van der Goes BY, Ravelli ACJ, et al. Perinatal mortality and morbidity in a nationwide cohort of 529 688 low-risk planned home and hospital births. BJOG. 2009;116:1177-1184.

Engle WA, Tomashek KM, Wallman C. Late-preterm infants: a population at risk. Committee on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1390-1401.

Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, et al. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75-84.

Goodman DC, Fisher ES, Little GA, et al. The relation between the availability of neonatal intensive care and neonatal mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1538-1544.

Gross SJ, Mettelman BB, Dye TD, et al. Impact of family structure and stability on academic outcome in preterm children at 10 years of age. J Pediatr. 2001;138:169-175.

Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: preliminary data for 2007. Natl Vital Stats Rep. 2009;57(12):1-23.

Heron M, Sutton PD, Xu J, et al. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2007. Pediatrics. 2010;125:4-15.

Howell EA, Hebert P, Chatterjee S, et al. Black/white differences in very low birth weight neonatal mortality rates among New York City hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e407-e415.

Kramer MS. Late preterm births: appreciable risks, rising incidence. J Pediatr. 2009;154:159-160.

Lawn JE, Cousens S, Bhutta ZA, et al. Why are 4 million newborn babies dying each year? Lancet. 2004;364:399-401.

MacDorman MF, Mathews TJ. Recent trends in infant mortality in the United States. NCHS Data Brief. 2008;9:1-8.

March of Dimes Foundation. White paper on preterm birth. http://marchofdimes.com/files/WhitePaperFINAL21Sep09.pdf#9. Accessed April 26, 2010

Mathews TJ, Minino AM, Osterman MJK, et al. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2008. Pediatrics. 2011;127:146-157.

Muglia LJ, Katz M. The enigma of spontaneous preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:529-535.

Tita AT, Landon MB, Spong CY, et al. Timing of elective repeat cesarean delivery at term and neonatal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:111-120.

Tyson JE, Parikh NA, Langer J, et al. Intensive care for extreme prematurity—moving beyond gestational age. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1672-1681.

U.S. Health and Human Services: Healthy people 2010, ed 2, vol 1–2, Washington, DC, 2000, US Government Printing Office (Conference ed in 2 vol) (GPO stock No. 017-001-00547-9).