Optic Nerve

Congenital Defects and Anatomic Variations

Aplasia

I. Aplasia of the optic nerve (Fig. 13.3) is rare, especially in eyes without multiple congenital anomalies.

IV. Histology

Hypoplasia

I. Although rare, hypoplasia (underdevelopment of the optic nerve) is more common than aplasia (congenital absence of the optic nerve).

A. Hypoplasia of the optic nerve is a major cause of blindness in children.

B. In optic nerve hypoplasia, a small optic disc with central vessels is present.

III. Visual acuity is generally markedly decreased.

IV. The cause is failure of the retinal ganglion cells to develop normally.

B. Histologically, the nerve shows partial or complete absence of neurites.

Dysplasia

Anomalous Shape of Optic Disc and Cup

A. Oval discs (vertically, horizontally, or obliquely elongated) are common.

B. They are congenital and nonprogressive.

II. Myopia (see later in this chapter and see Chapter 11)

III. Congenital excavation of optic disc (i.e., an exaggeration of physiologic cup)

IV. Pseudoneuritis or pseudopapilledema (i.e., the opposite of congenital excavation)

B. Often, it is associated with hypermetropia or drusen of the optic nerve head.

Congenital Crescent or Conus

Congenital (Familial) Optic Atrophies

I. Simple recessive congenital optic atrophy

A. It has an autosomal-recessive inheritance pattern and significant visual disability.

C. Histology—see Optic Atrophy later in this chapter.

II. Behr’s syndrome

B. One form of Behr’s syndrome has been reported in Iraqi Jews who have 3-methylglutaconic aciduria.

C. Histology—see Optic Atrophy later in this chapter.

III. Dominant optic atrophy (Kjer)

B. The visual loss in dominant optic atrophy (Kjer type) has an insidious onset in approximately the first five years of life, with considerable variation in families. Approximately 58% of affected patients have onset of symptoms before the age of 10 years.

1. Long-term visual prognosis is relatively good, with stable or slow progression of visual loss.

C. Histology—see Optic Atrophy later in this chapter.

IV. Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON)

A. LHON, one of the mitochondrial myopathies (see Chapter 14), is inherited through the maternal transmission of one or more mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations.

1. At least 11 pathogenetic point mutations of mtDNA have been described.

4. Class I/II contains two mutations that have an intermediate effect between classes I and II.

C. LHON is characterized by a subacute, sequential, bilateral, central loss of vision mainly in young men (usually between the ages of 18 and 30 years). Color vision is affected early.

D. Histology—see Optic Atrophy later in this chapter.

Coloboma (Table 13.1)

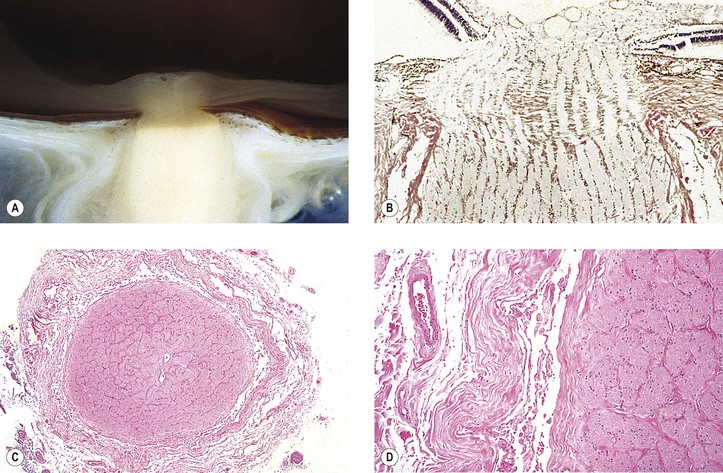

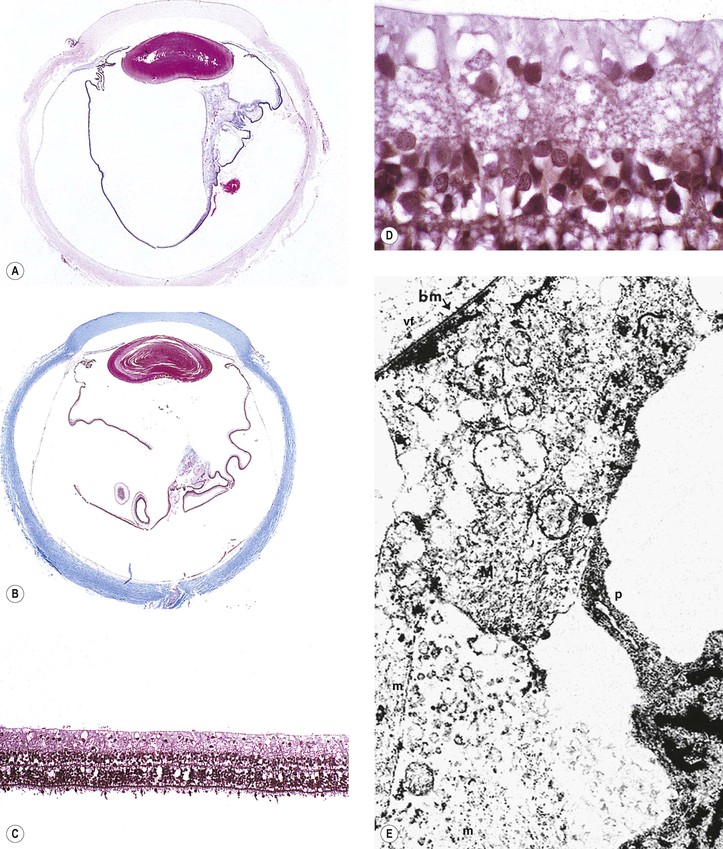

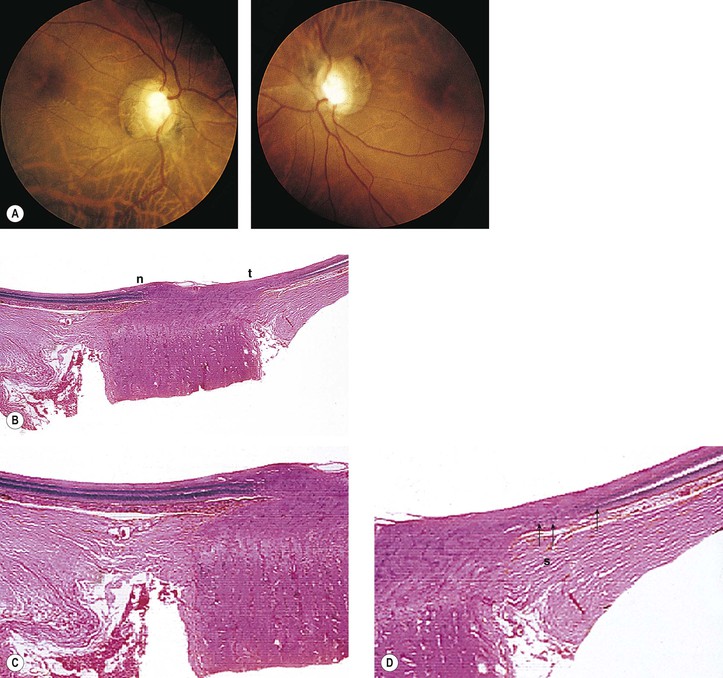

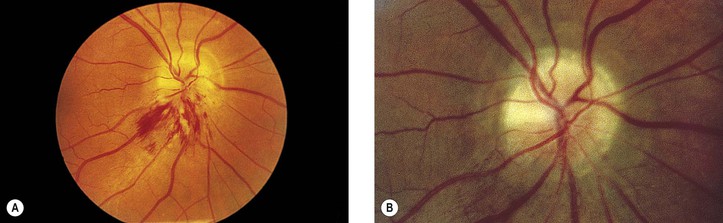

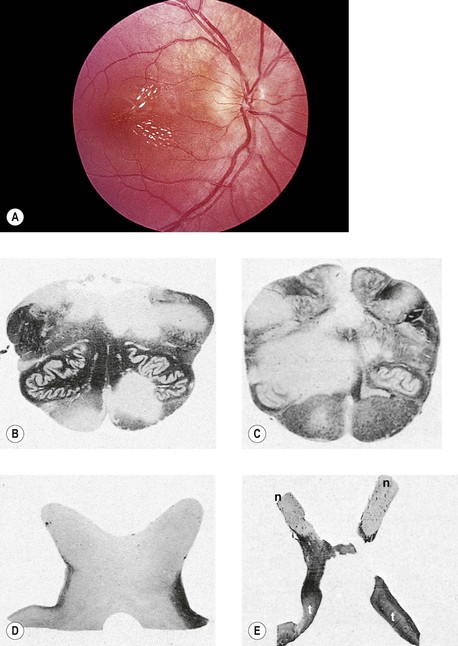

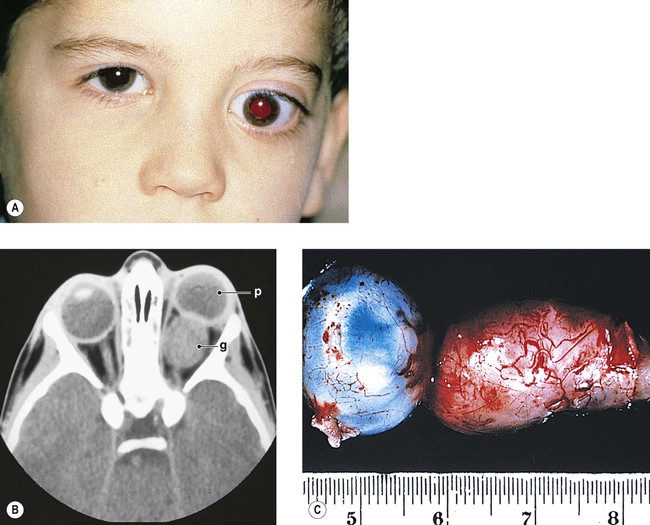

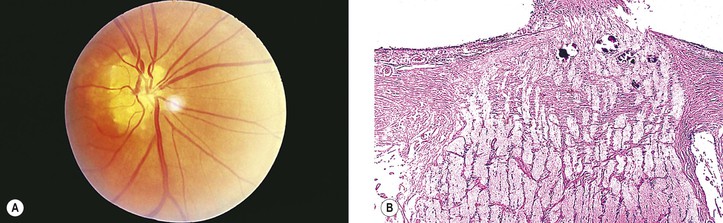

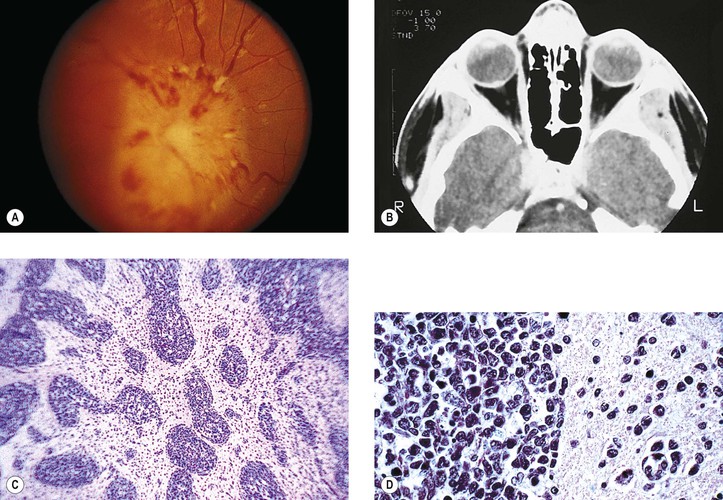

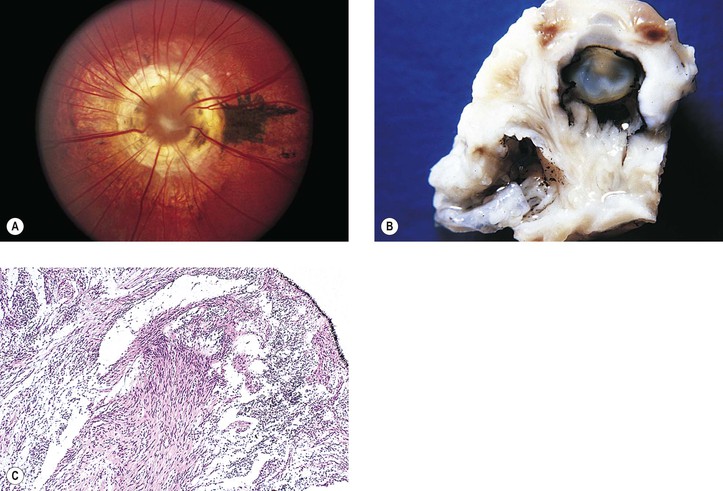

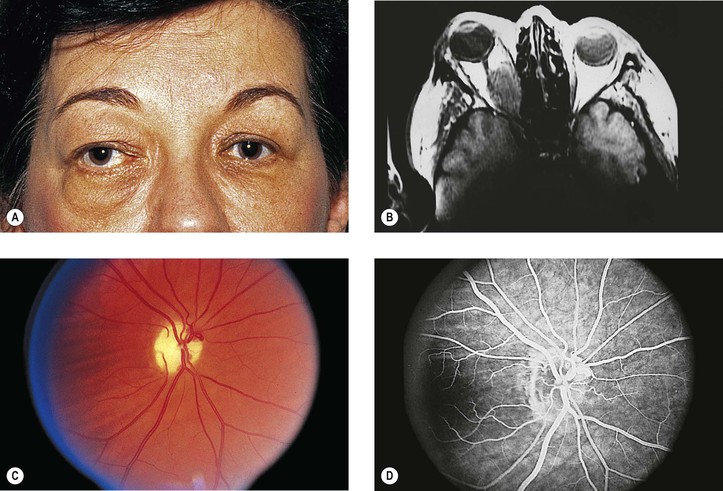

I. A coloboma (Figs. 13.4 and 13.5) may involve the optic disc alone or may be part of a complete coloboma involving the entire embryonic fissure.

B. The surrounding retina may be involved.

IV. Vision may be normal but is usually defective.

V. Histologically, the coloboma appears as a large defect at the side of the nerve usually involving the neural retina, choroid, and sclera.

B. The wall of the defect may contain adipose tissue and even smooth muscle cells.

C. The coloboma may protrude into the retrobulbar tissue and cause microphthalmos with cyst (see Figs. 13.4B and 13.4C and Chapter 14).

VI. An optic nerve pit (see Fig. 13.5) is a form of coloboma of the optic nerve that shows a small, circular or triangular depression approximately one-eighth to one-half the diameter of the optic disc, usually located in the inferotemporal quadrant of the disc.

B. The optic disc is usually of greater size than the one in the uninvolved fellow eye.

VII. Morning glory syndrome (see Fig. 13.4A) is a form of coloboma of the optic nerve that shows an enlarged, deeply excavated optic disc, resembling the morning glory flower.

A. Although the condition is usually unilateral, rare bilateral cases have been reported.

B. Girls are affected twice as often as boys, and visual acuity is usually poor.

D. The demarcation of the elevated peripapillary tissue and normal surrounding retina is indistinct.

VIII. Choristoma

A. Rarely, choristomatous elements can be found in the optic nerve in the absence of a coloboma.

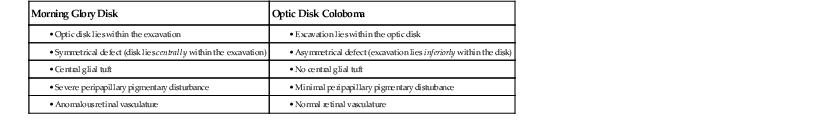

TABLE 13.1

Ophthalmoscopic Findings That Distinguish Morning Glory Disk Anomaly from Optic Disk Coloboma

| Morning Glory Disk | Optic Disk Coloboma |

(From Brodsky MC: Congenital optic disk anomalies. Surv Ophthalmol 39:89, 1994.)

Myopia

I. Even before the onset of juvenile myopia, children of myopic parents have longer-than-normal eyes (Fig. 13.6; see Chapter 11).

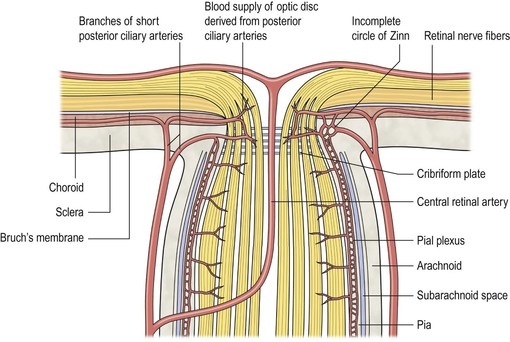

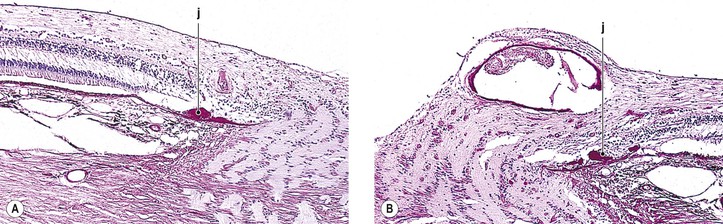

IV. Histologically, the optic nerve passes obliquely through the scleral canal.

A. Temporal side of optic disc

1. The RPE and Bruch’s membrane do not extend to the temporal margin of the optic disc.

Optic Disc Edema

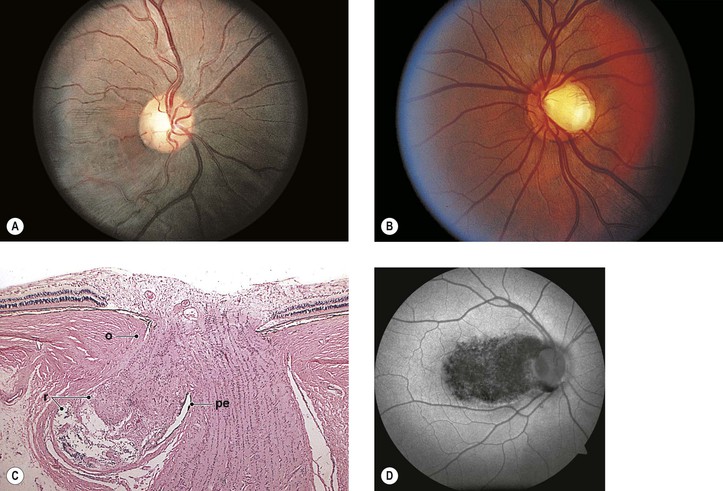

General Information (Fig. 13.7; see Fig. 13.22)

Causes

Pseudopapilledema

Optic disc edema may be simulated by hypermetropic optic disc, drusen of optic nerve head, congenital developmental abnormalities, optic neuritis and perineuritis, and myelinated (medullated) nerve fibers.

Histology of Optic Disc Edema

I. Acute (see Fig. 13.7)

A. Edema and vascular congestion of the nerve head result in increased tissue volume.

1. Hemorrhages may be seen in the optic nerve or in the retinal nerve fiber layer.

2. The increased tissue mass causes the physiologic cup to narrow.

B. The aforementioned changes result in a displacement of the neural retina away from the edge of the optic disc.

1. The outer layers of the neural retina may buckle (retinal and choroidal folds are seen clinically).

2. The rods and cones are displaced away from the end of Bruch’s membrane.

II. Chronic

Optic Neuritis

In general, visual acuity is severely affected.

Causes

I. Secondary to ocular disease (e.g., acute corneal ulcer, anterior or posterior uveitis, endophthalmitis or panophthalmitis, and retinochoroiditis; see Fig. 4.26)

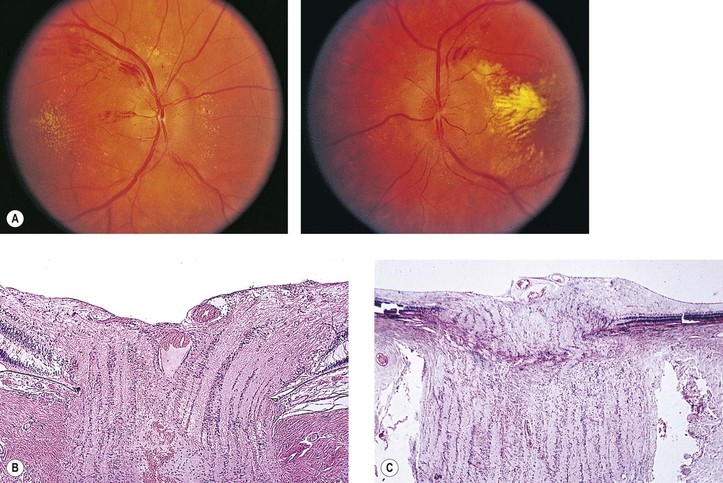

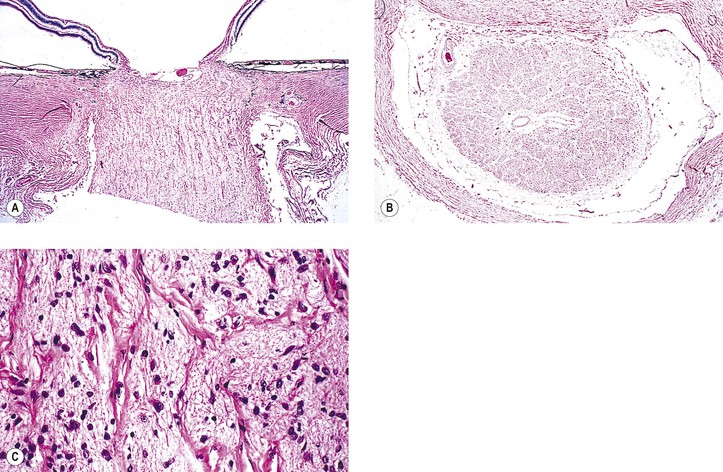

II. Secondary to orbital disease [Fig. 13.8; e.g., as bilateral idiopathic inflammation of the optic nerve sheaths, cellulitis (may be primary but more commonly secondary to sinusitis), thrombophlebitis, arteritis, and midline granuloma syndrome]

III. Secondary to intracranial disease (e.g., meningitis, encephalitis, and meningoencephalitis)

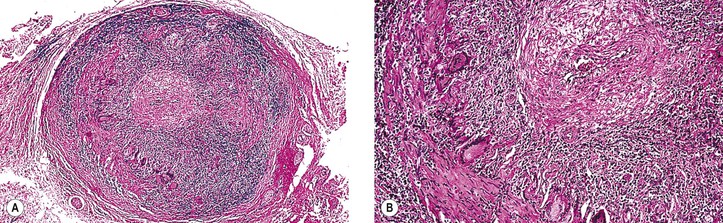

V. Secondary to vascular disease [Figs. 13.9 and 13.10; e.g., temporal arteritis, periarteritis nodosa, pulseless (Takayasu’s) disease, and arteriosclerosis]

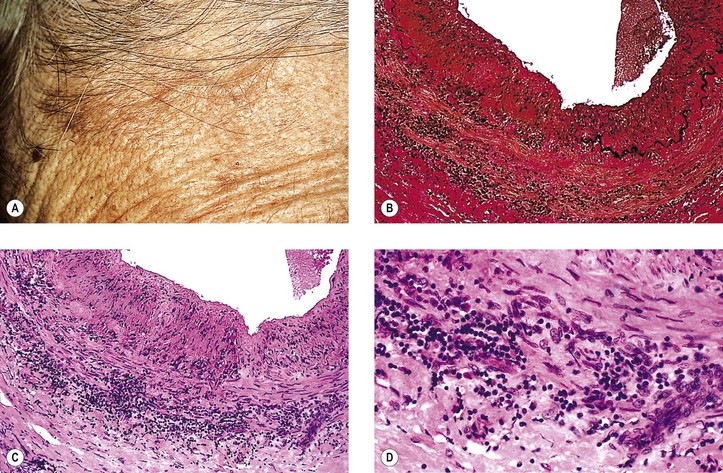

A. Temporal (cranial, giant cell) arteritis (see Figs. 13.9 and 13.10)

5. Marked impairment of visual acuity, often with involvement of the second eye within days or weeks of involvement of the first eye, is the most frequent ocular problem, but ptosis and muscle palsies may also occur.

a. Approximately 14–27% of patients have permanent visual loss.

7. Histologically, a granulomatous reaction centering about a fragmented internal elastic lamina and spreading into the media and adventitia of the temporal artery is characteristic.

a. Giant cells are frequently present (see Fig. 13.10) but may be absent (see Fig. 13.9). Rarely, a chronic nongranulomatous reaction with lymphocytes and plasma cells without epithelioid or giant cells is seen (see Fig. 13.9).

B. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (ANION; Fig. 13.11)

3. The other eye is involved in approximately 15% of patients over a five-year period.

4. The ESR is usually less than 44 mm/hour, unlike the elevated ESR in temporal arteritis.

6. A condition that has numerous similarities to ANION (abrupt onset, absence of ocular pain, altitudinal field loss, and lack of subsequent improvement) is called neuroretinitis (previously called Leber’s stellate maculopathy).

VI. Secondary to demyelinating disease

A. Multiple sclerosis (Fig. 13.12; see Fig. 13.11)

b. The ophthalmoscopic appearance may be normal, or papillitis may simulate optic disc edema.

c. Associated sheathing of retinal veins is seen in 10–20% of patients.

B. Neuromyelitis optica (encephalomyelitis optica; Devic’s disease) consists of bilateral optic atrophy and paraplegia.

a. The loss of vision is acute in onset and rapid in progression, even to complete blindness.

2. Extraocular muscle palsies and nystagmus may be seen infrequently.

C. Diffuse cerebral sclerosis primarily involves white matter of the CNS and includes Schilder’s disease (Fig. 13.13), Krabbe’s disease, Pelizaeus–Merzbacher syndrome, adrenoleukodystrophy, and metachromatic leukodystrophy.

VIII. Secondary to hereditary conditions (see later in this chapter)

Histology of Optic Neuritis

B. Topographic histologic classification of optic neuritis

II. Specific types of tissue reaction

A. Inflammatory disease: the types of inflammatory disease of the optic nerve depend on the cause (see Figs. 13.8 and 13.13; see also Fig. 4.26; see section on Inflammation in Chapter 1 and see Chapters 3 and 4).

B. Vascular disease: the clinicopathologic picture depends on the type of vascular disease involving the optic nerve.

1. Temporal (cranial) arteritis: a granulomatous arteritis (see Figs. 13.9 and 13.10)

2. Nonarteritic (ischemic) optic neuropathy (see Fig. 13.11)

4. Pulseless disease and arteriosclerosis: coagulative or ischemic type of necrosis

1. Demyelinating stage (see Figs. 13.11–13.13)

a. Early breakdown of myelin sheaths occurs. Macrophages phagocytose the disintegrated myelin.

2. Healing stage (see Fig. 13.13B)

a. Astrocytic response occurs in areas of demyelination.

b. Ultimately, the area of involvement shows gliosis.

D. Nutritional or toxic or metabolic diseases

Optic Atrophy*

Causes

A. The primary lesion is in the neural retina or optic disc—for example, glaucoma* (see Figs. 16.32 and 16.33), retinochoroiditis,† retinitis pigmentosa,† traumatic or secondary retinitis pigmentosa,† central retinal artery occlusion* (see Fig. 11.10), chronic optic disc edema,† toxic or nutritional causes (e.g., chloroquine*), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD).*

1. AD

B. The secondary effects are on the optic nerve and white tracts in the brain.

A. The primary lesion is in the brain or optic nerve [e.g., tabes dorsalis,* Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease,* hydrocephalus,* meningioma* (see Figs. 13.18 and 13.19), ONG,* and traumatic transection of the optic nerve*]; toxic or nutritional causes (e.g., methyl alcohol*); and genetically determined disorders* [e.g., Schilder’s disease (see Fig. 13.13), Pelizaeus–Merzbacher syndrome, adrenoleukodystrophy, and Krabbe’s disease].

B. The secondary effects are on the optic disc and neural retina.

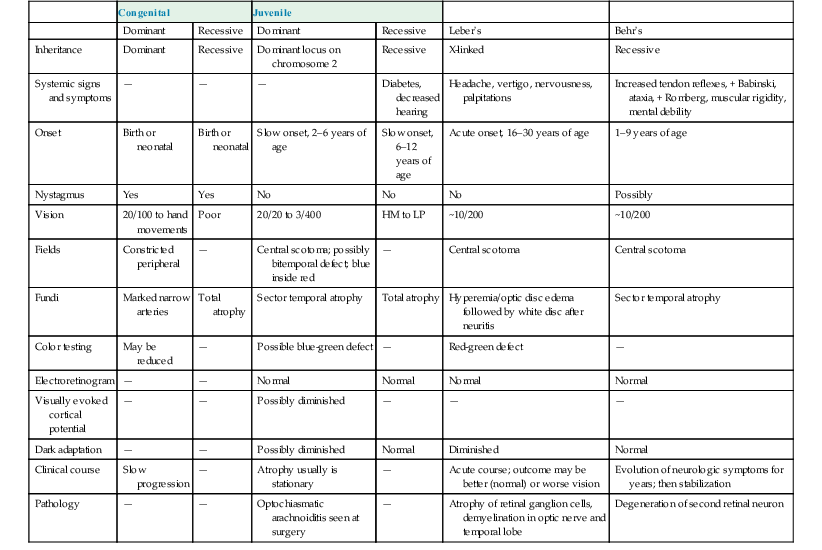

A. Familial optic atrophies (Table 13.2; see subsection Congenital (Familial) Optic Atrophies in this chapter)

TABLE 13.2

Optic Atrophies

| Congenital | Juvenile | |||||

| Dominant | Recessive | Dominant | Recessive | Leber’s | Behr’s | |

| Inheritance | Dominant | Recessive | Dominant locus on chromosome 2 | Recessive | X-linked | Recessive |

| Systemic signs and symptoms | — | — | — | Diabetes, decreased hearing | Headache, vertigo, nervousness, palpitations | Increased tendon reflexes, + Babinski, ataxia, + Romberg, muscular rigidity, mental debility |

| Onset | Birth or neonatal | Birth or neonatal | Slow onset, 2–6 years of age | Slow onset, 6–12 years of age | Acute onset, 16–30 years of age | 1–9 years of age |

| Nystagmus | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Possibly |

| Vision | 20/100 to hand movements | Poor | 20/20 to 3/400 | HM to LP | ~10/200 | ~10/200 |

| Fields | Constricted peripheral | — | Central scotoma; possibly bitemporal defect; blue inside red | — | Central scotoma | Central scotoma |

| Fundi | Marked narrow arteries | Total atrophy | Sector temporal atrophy | Total atrophy | Hyperemia/optic disc edema followed by white disc after neuritis | Sector temporal atrophy |

| Color testing | May be reduced | — | Possible blue-green defect | — | Red-green defect | — |

| Electroretinogram | — | — | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Visually evoked cortical potential | — | — | Possibly diminished | — | — | — |

| Dark adaptation | — | — | Possibly diminished | Normal | Diminished | Normal |

| Clinical course | Slow progression | — | Atrophy usually is stationary | — | Acute course; outcome may be better (normal) or worse vision | Evolution of neurologic symptoms for years; then stabilization |

| Pathology | — | — | Optochiasmatic arachnoiditis seen at surgery | — | Atrophy of retinal ganglion cells, demyelination in optic nerve and temporal lobe | Degeneration of second retinal neuron |

(Modified from Caldwell JBH, Howard RO, Riggs LA: Dominant juvenile optic atrophy: A study of two families and review of the hereditary disease in childhood. Arch Ophthalmol 85:133–147, 1971. © American Medical Association. All rights reserved.)

B. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G-6-PD) Worcester

Histology of Optic Atrophy

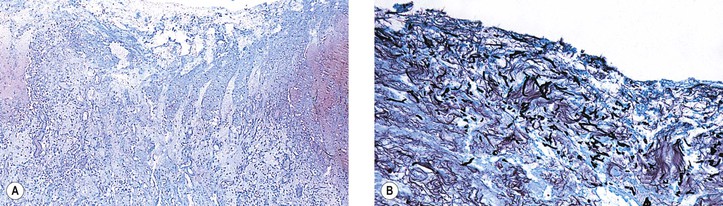

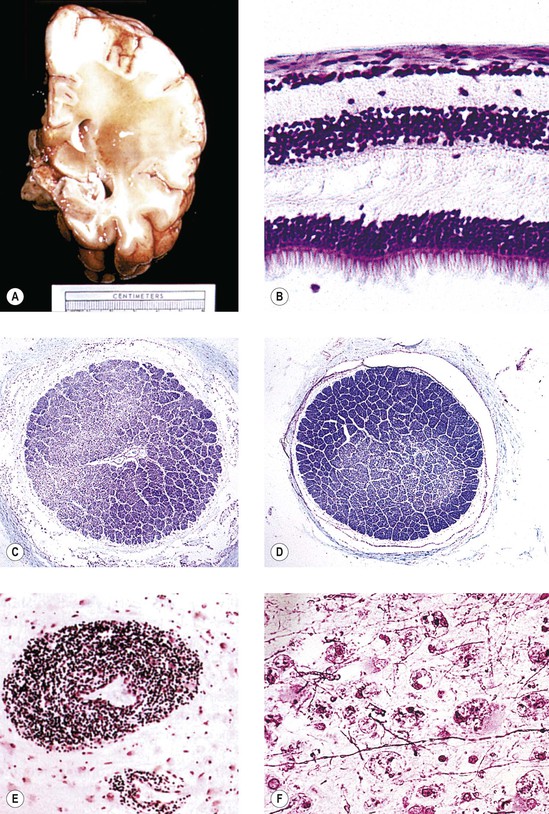

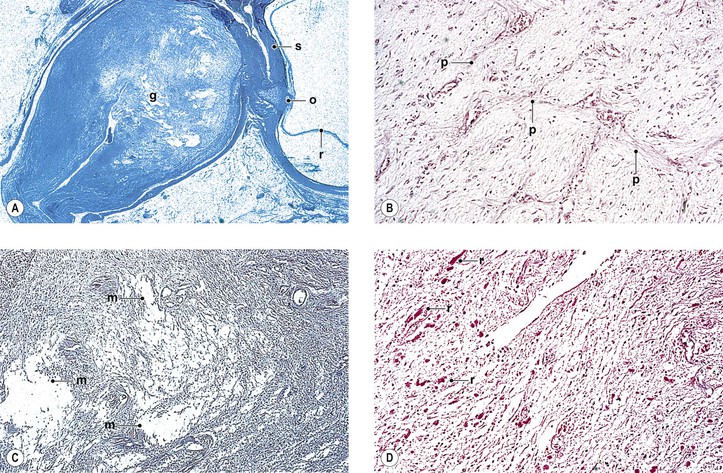

I. Shrinkage or loss of parenchyma and loss of both myelin and axis cylinders are seen (Figs. 13.14 and 13.15; see Fig. 13.13).

A. Shrinkage results in widening of the subarachnoid and subdural spaces and redundancy of the dura.

B. Pial septa widen to occupy the space made by the loss of parenchyma.

C. The normal spongy texture of the optic nerve is lost.

II. Optic nerve gliosis and proliferation of astrocytes are prominent.

III. The physiologic cup widens or deepens and results in a baring of the lamina cribrosa.

A. Glial proliferation on the surface of the disc results in a “secondary” optic atrophy.

B. Hyaluronic acid accumulates in the anterior portion of the optic nerve [i.e., cavernous (Schnabel’s) optic atrophy; see Fig. 16.33] after long-standing glaucoma (see Chapter 16).

Injuries

See Chapter 5.

Tumors

Primary

I. “Glioma” (more properly called juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma) of optic nerve (Figs. 13.16 and 13.17)

A. The prevalence is slightly greater in girls than in boys.

B. Proptosis, predominantly temporal, is the most common presenting sign; loss of vision is the next most common sign.

D. Optic disc edema followed by optic atrophy is a frequent clinical finding.

E. The ONG is most often located in the orbital portion of the optic nerve alone, with combined involvement of both orbital and intracranial portions next most common (Table 13.3).

G. The mortality rate is significant.

2. With involvement of the intracranial optic nerve, the prognosis is guarded.

H. Histology

1. Three main patterns may all be present in different parts of the same tumor:

c. Astrocytic areas: the areas resemble juvenile astrocytomas of the cerebellum and are probably the same type of tumor.

1) The cellular areas show spindle cell formation.

2) Rosenthal fibers, which are cytoplasmic, eosinophilic structures in astrocytes, may be prominent.

a. Infiltration by the ONG through the pia with resultant arachnoid hyperplasia is seen.

b. The tumor itself may enlarge the optic foramen (as may proliferating meningothelial cells).

c. The ONG may cause edema or atrophy of the optic nerve.

d. The ONG may infiltrate the optic nerve head or compress or occlude the central retinal vein.

TABLE 13.3

Juvenile Pilocytic Astrocytoma of the Optic Nerve: Location of Astrocytoma

| Location | No. | % |

| Orbital | 27 | 47 |

| Intracranial and orbital | 15 | 26 |

| Intracranial | 6 | 10 |

| Intracranial and chiasm | 7 | 12 |

| Chiasm | 3 | 5 |

| Total | 58 | 100 |

(Adapted from Yanoff M et al.: Juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma [“glioma”]. In Jakobiec FA, ed: Ocular and Adnexal Tumors. Birmingham, AL, Aesculapius, 1978:685.)

II. Other astrocytic neoplasms

A. Oligodendrocytomas are rare.

B. Rarely, malignant astrocytic neoplasms may involve the optic nerve primarily, most commonly in adults. Histologically, the neoplasms are marked by areas of anaplasia and classed as low-grade astrocytomas, anaplastic astrocytomas, and glioblastoma multiforme.

1. Necrosis is the sine qua non of glioblastoma multiforme.

2. DNA analysis, combined with histologic grading, improves prognosis designation.

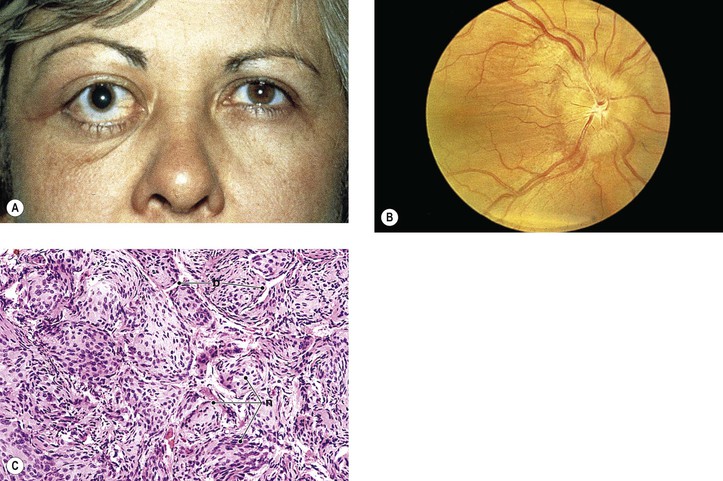

III. Meningioma (Figs. 13.18 and 13.19)

B. The average age at onset is 32 years (range, 3.5–73 years), with the median 38 years.

C. The main clinical presentations are loss of vision and progressive exophthalmos.

D. Optociliary (opticociliary) shunt vessels may be seen in approximately 25% of cases.

E. There may be associated neurofibromatosis (mainly NF-2) in 16% of patients.

F. The prognosis for life depends somewhat on age at onset.

G. Histologically, the tumors have a meningotheliomatous or a mixed-type pattern.

1. Fibroblastic and angiomatous types of meningiomas rarely occur primarily in the orbit.

2. Frequently, meningiomas extend extradurally to invade the orbital tissue.

3. Uncommonly, they invade the optic nerve and sclera and may even invade into the choroid and retina.

IV. Melanocytoma (see Chapter 17)

V. Hemangioma is usually associated with the phakomatoses (see Chapter 2).

VI. Medulloepithelioma may rarely arise from the distal end of the optic nerve (see Chapter 17).

VII. Giant drusen of the anterior portion of the optic nerve are astrocytic hamartomas usually associated with tuberous sclerosis (see Chapter 2).

VIII. Ordinary drusen of the anterior portion of the optic nerve (Fig. 13.20)

D. Hemorrhage of the optic disc is a rare complication.

1. The hemorrhage may extend into the vitreous or under the surrounding retina.

2. Peripapillary subretinal neovascularization may occur.

X. Corpora amylacea—these are intracellular, basophilic, periodic acid–Schiff-positive structures often observed in the white matter of the brain, including optic nerve and neural retina (mainly nerve fiber layer).

B. They have no clinical significance and are considered an aging phenomenon.

XI. Corpora arenacea (psammoma bodies)

A. These are laminated, basophilic bodies produced by the arachnoid meningothelial cells.

B. They are of no clinical significance and are an aging phenomenon.

XIII. Choristoma

XIV. Buscaiano bodies resemble corpora amylacea but are fixation artifacts.

Secondary

II. Malignant melanoma of choroid

III. Pseudotumor of RPE

VI. Glioblastoma multiforme of brain

VII. Lymphoma or leukemia (Fig. 13.22)

VIII. Macroscopically, artifacts may simulate secondary (or primary) optic nerve tumors (e.g., myelin).

Access the complete reference list online at ![]()