Ocular Melanocytic Tumors

Normal Anatomy

Ocular Melanocytes

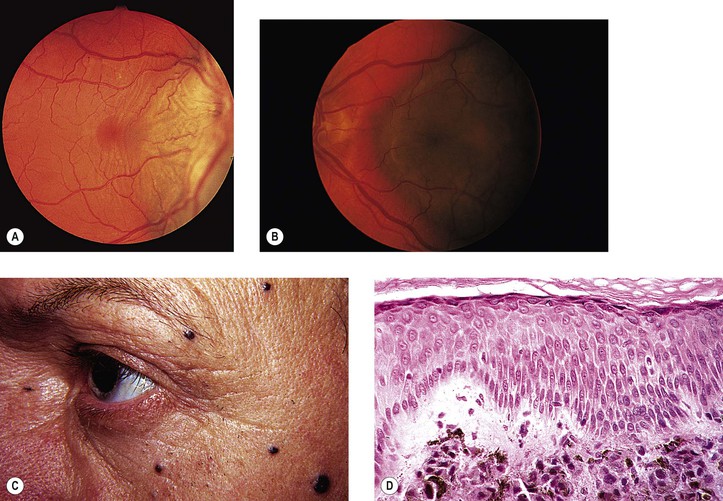

I. Conjunctival and uveal melanocytes (Fig. 17.1) are derived from the neural crest; pigment epithelial (PE) cells are derived from neuroepithelium or the layers of the optic cup.

II. Dermal and conjunctival melanocytes are solitary dendritic cells.

VI. Normal PE tends to vary little, if at all, among the races, and always appears heavily pigmented.

VIII. The PE readily undergoes reactive proliferation but rarely becomes neoplastic.

Melanotic Tumors of Eyelids

Ephelis (Freckle)

Lentigo

I. Lentigo

A. Lentigo is similar clinically to an ephelis but is somewhat larger.

C. Multiple lentigines syndrome

D. Lentigo maligna (melanotic freckle of Hutchinson; circumscribed precancerous melanosis of Dubreuilh; Fig. 17.2)

1. Lentigo maligna occurs as an acquired pigmented lesion, mostly in adults older than 50 years of age.

2. It appears as a brown or black flat lesion, usually on the face, sometimes with involvement of the eyelids and conjunctiva (see subsection Primary Acquired Melanosis in section Melanotic Tumors of Conjunctiva, later), enlarging slowly in an irregular manner.

Nevus1

A. A nevus is a congenital, hamartomatous tumor, flat or elevated, and usually well-circumscribed lesion.

1. It may be pigmented early in life or not until puberty or even early adulthood.

2. The nevus is composed of nevus cells that are atypical but benign-appearing dermal melanocytes.

B. Five types: (1) junctional, (2) intradermal (Fig 17.3), (3) compound (Fig. 17.4), (4) blue (Fig. 17.5), and (5) congenital oculodermal melanocytosis (nevus of Ota) (Fig. 17.6)

C. The familial atypical mole and melanoma (FAM-M) syndrome (dysplastic nevus syndrome; B–K mole syndrome)

2. The nevi appear at an early age (usually during adolescence) and increase in number throughout life.

3. Familial cases are inherited in an autosomal-dominant pattern; sporadic cases also occur.

II. Junctional nevus

A. A junctional nevus is flat, well circumscribed, and a uniform brown color.

B. The nevus cells are located at the “junction” of the epidermis and dermis (see Fig. 17.4C).

C. The nevus has a low malignant potential.

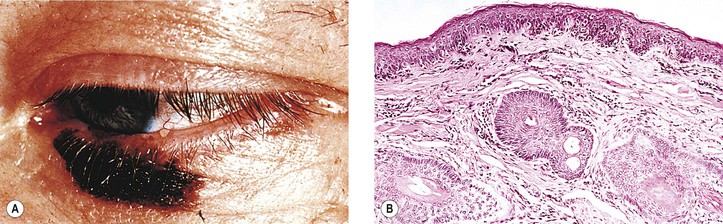

III. Intradermal nevus (common mole; see Fig. 17.3)

B. It has a brown to black color when pigmented; often, however, it is “flesh-colored.”

C. The nevus cells are entirely in the dermis.

2. No inflammatory cells are present unless the nevus is inflamed secondarily.

D. The nevus may be seen with proliferated Schwann elements (i.e., a neural nevus).

E. An unusual intradermal (or subepithelial) nevus is the peripunctal melanocytic nevus.

2. The nevus cells are subepithelial and also infiltrate the orbicularis muscle fibers.

F. Intradermal nevus probably has no malignant potential.

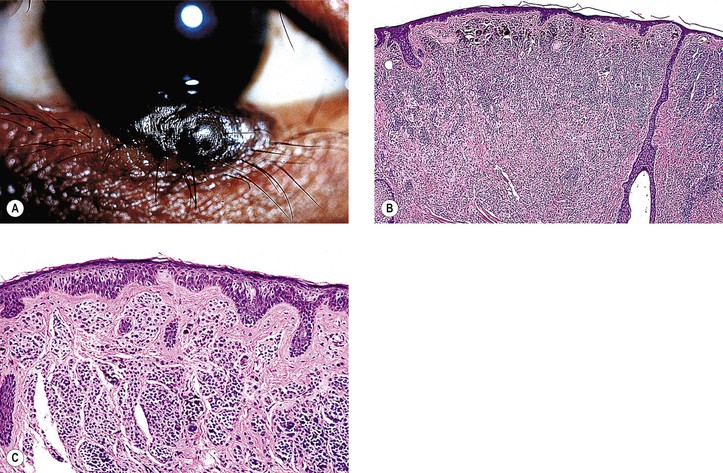

IV. Compound nevus (see Fig. 17.4)

A. It combines junctional and dermal components, and it is usually brown.

B. The dermal component shows a normal polarity (see Fig. 17.4; i.e., cells closest to the epidermis are larger, plumper, rounder, and paler than the deeper cells).

C. Spindle cell nevus (juvenile “melanoma,” Spitz nevus) is a special form of compound nevus that occurs predominantly in children, often as a solitary lesion on the face.

1. Histologically, it superficially resembles a malignant melanoma, but biologically it is benign.

V. Blue nevus

A. Blue nevus is usually flat and almost always pigmented from birth, appearing blue to slate-gray.

B. Nevus cells are present deep in the dermis in interlacing fasciculi.

1. The cells are located deeper than junctional, dermal, or compound nevus cells.

3. It may be very cellular [i.e., a cellular blue nevus (see Fig. 17.5), which has a low malignant potential].

C. Unless the nevus is the large or giant congenital cellular type, it has no malignant potential.

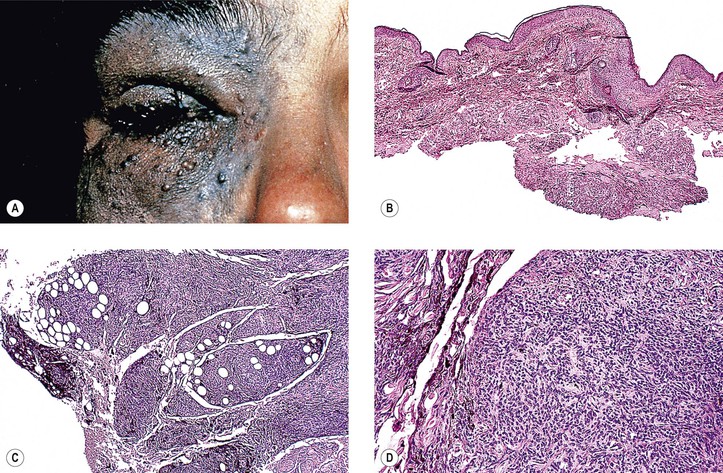

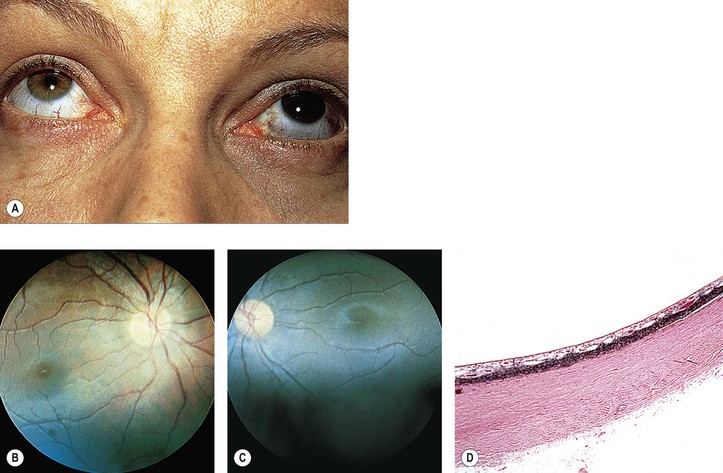

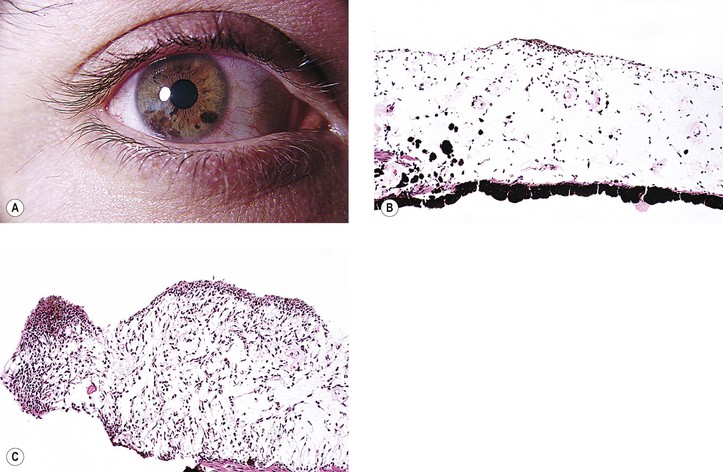

VI. Congenital oculodermal melanocytosis (nevus of Ota; see Fig. 17.6)

A. The condition can be considered a type of blue nevus of the skin around the orbit (in the distribution of the ophthalmic, maxillary, and occasionally mandibular branches of the trigeminal nerve), associated with an ipsilateral blue nevus of the conjunctiva and a diffuse nevus of the uvea (i.e., ipsilateral congenital ocular melanocytosis).

1. Skin pigmentation is usually prominent, but it may be quite subtle.

2. It is quite common in black and Asian patients but unusual in white patients.

3. Rarely, congenital oculodermal melanocytosis is bilateral.

B. The diffuse uveal involvement causes heterochromia iridum (i.e., the involved eye is darker than the uninvolved iris).

Heterochromia iridum (see Table 17.2) is a difference in pigmentation between the two irises, as contrasted to heterochromia iridis, which is an alteration within a single iris (e.g., occasionally, ipsilateral segmental heterochromia is caused by segmental ocular involvement; the alteration of pigmentation in the single iris is properly called heterochromia iridis).

D. Congenital ocular melanocytosis (see earlier)

E. Congenital oculodermal melanocytosis is potentially malignant only when it occurs in white patients.

Malignant melanomas have been reported in the skin, conjunctiva, uvea (most common), orbit (rarely), and even in the meninges.

Malignant Melanoma

I. General information (Figs. 17.7 and 17.8)

2. An emerging epidemic of melanoma appears to be on the horizon.

B. Melanoma involves the lower lid two-thirds more often than the upper lid.

C. Associated histologic findings include solar elastosis, nevus, and basal cell carcinoma.

D. Cuticular melanomas show a nonrandom alteration of chromosome 6.

III. Skin melanomas are not classified according to cell type, as are uveal melanomas.2

B. Superficial spreading malignant melanoma

1. This type has only a vertical growth phase, involves the dermis early, and has the worst prognosis.

D. Acrolentiginous melanoma occurs on the palms, soles, and terminal phalanges.

F. Mucous membrane malignant melanoma (see discussion of conjunctival melanoma, later in this chapter).

Rarely, a primary lid melanoma can occur in conjunction with an ipsilateral primary conjunctival melanoma.

IV. Histology

A. Normal polarity is lost (i.e., the deep cells are indistinguishable from superficial cells).

B. The overlying epithelium is invaded.

C. The cells of the neoplasm are atypical.

1. The nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio is increased, and large abnormal cells may be seen.

2. Mitotic figures may be present, but frequently they are absent.

D. Often, an underlying inflammatory infiltrate of round cells, predominantly lymphocytes, is present.

2. Mitotic figures are usually present in the dermal component.

3. Melanomas greater than 1.5 mm in depth carry a distinctly worse survival rate.

V. Prognosis

B. Superficial, spreading malignant melanoma has a 75% survival rate.

D. The level of expression of at least three integrin subunits is correlated with melanoma progression.

Melanotic Tumors of Conjunctiva

Ephelis (Freckle)

I. An ephelis (freckle) is a brown, patchy, flat lesion with irregular borders, most often involving the bulbar conjunctiva near the limbus but sometimes the bulbar or palpebral conjunctiva.

A. The pigmented conjunctiva is movable over the sclera.

B. The lesion is present at birth.

Nevus

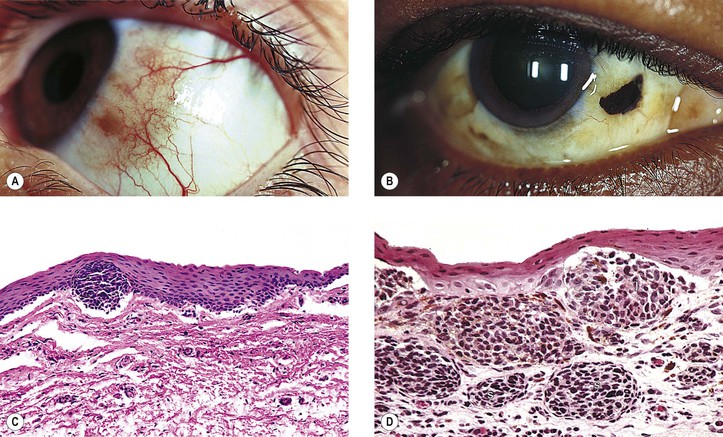

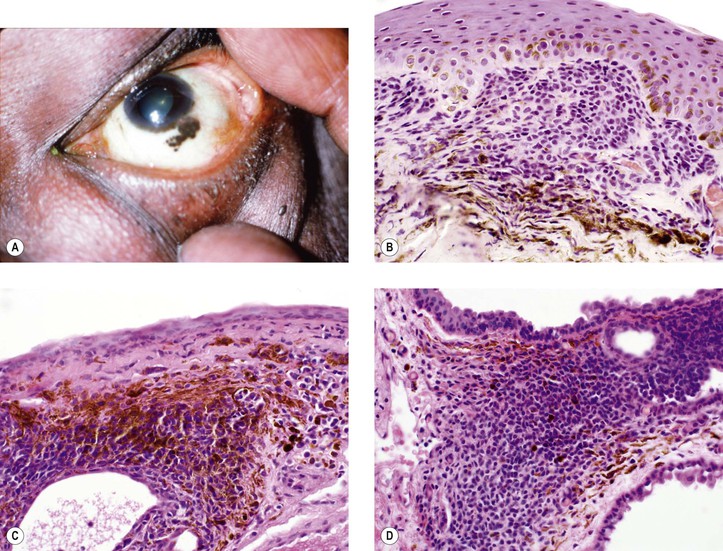

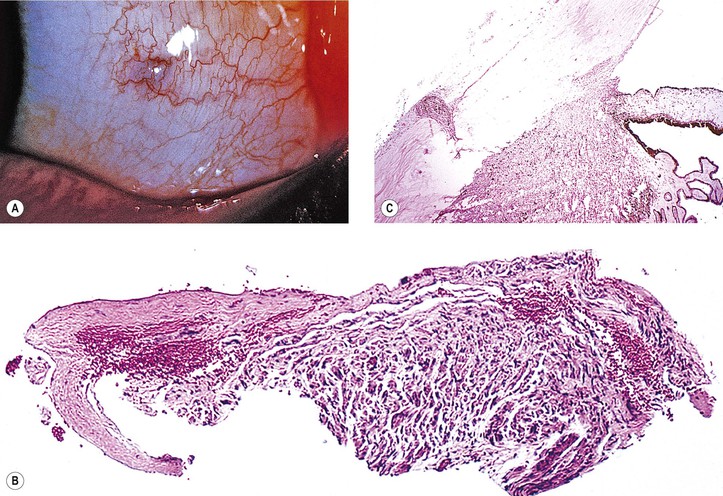

I. General information (Figs. 17.9–17.12)

A. A nevus is a hamartomatous, congenital, flat or elevated, well-circumscribed lesion that may not become pigmented until puberty or early adulthood.

2. They are almost entirely restricted to the epibulbar surface, the plica, the caruncle (see Fig. 17.11), and the lid margin.

4. Nevi are rarely located in the palpebral conjunctiva (1%), fornix (1%), or cornea (<1%).

5. Over time, a change in color may be seen in 13% of lesions, and the size may change in 8%.

C. A nevus is the most common conjunctival tumor and consists of five “classic” types:

1. Junctional

2. Subepithelial (analogous to intradermal nevus of skin)

3. Compound

4. Blue

a. Congenital ocular melanocytosis (melanosis oculi)

b. Congenital oculodermal melanocytosis (nevus of Ota)

6. Unusual types of conjunctival nevi

II. Junctional nevus (Table 17.1; see Fig. 17.9C)

A. It is similar in appearance to junctional nevus of the skin.

B. Nevus moves with conjunctiva over sclera.

C. Histologically, nevus cells appear more “worrisome” than those of skin junctional nevi.

1. Cells tend to be larger and may reach the external surface of the epidermis.

D. Malignant potential is low.

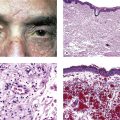

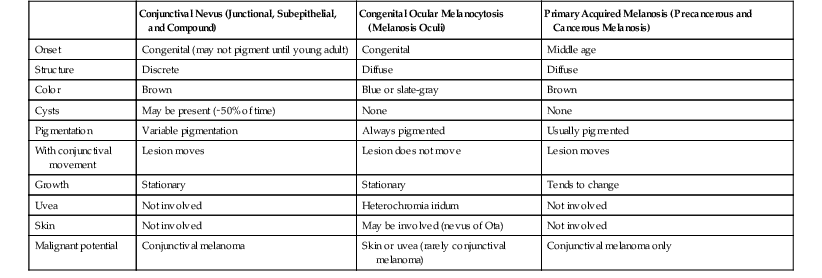

TABLE 17.1

Conjunctival Nevus, Congenital Ocular Melanocytosis, and Primary Acquired Melanosis Compared

| Conjunctival Nevus (Junctional, Subepithelial, and Compound) | Congenital Ocular Melanocytosis (Melanosis Oculi) | Primary Acquired Melanosis (Precancerous and Cancerous Melanosis) | |

| Onset | Congenital (may not pigment until young adult) | Congenital | Middle age |

| Structure | Discrete | Diffuse | Diffuse |

| Color | Brown | Blue or slate-gray | Brown |

| Cysts | May be present (∼50% of time) | None | None |

| Pigmentation | Variable pigmentation | Always pigmented | Usually pigmented |

| With conjunctival movement | Lesion moves | Lesion does not move | Lesion moves |

| Growth | Stationary | Stationary | Tends to change |

| Uvea | Not involved | Heterochromia iridum | Not involved |

| Skin | Not involved | May be involved (nevus of Ota) | Not involved |

| Malignant potential | Conjunctival melanoma | Skin or uvea (rarely conjunctival melanoma) | Conjunctival melanoma only |

III. Subepithelial nevus (see Table 17.1)

B. Nevus moves with conjunctiva over sclera.

C. It is not nearly as common as a junctional or compound nevus.

E. It probably has no malignant potential.

IV. Compound nevus (see Table 17.1 and Figs. 17.9D and 17.10)

A. It is quite similar to compound nevus of the skin; appears brown when pigmented.

B. Nevus moves with conjunctiva over sclera.

D. The subepithelial hamartomatous component, in addition to containing nevus cells, frequently contains epithelial embryonic rests, which may develop into epithelial cysts (i.e., a cystic nevus; see Fig. 17.10).

1. The epithelial component is present in approximately 50% of conjunctival nevi.

E. Spindle cell nevus (Spitz nevus; juvenile melanoma)

1. This special form of compound nevus occurs predominantly in children, but it may be found in adults.

2. Histologically, it is similar to “juvenile melanoma” of the skin.

F. Malignant potential is extremely low.

V. Blue nevus

B. It does not move with the conjunctiva over the sclera.

C. Histologically, nevus cells, mainly deeply pigmented, are seen deep in the subepithelial tissue in interlacing fasciculi.

2. When very cellular, the nevus is called a cellular blue nevus.

a. It appears as a localized blue nodule.

b. It rarely becomes malignant.

E. Only the cellular type is potentially malignant.

F. The combined nevus is composed of nevocellular and blue nevus elements (see Fig. 17.12). The nevocellular component may be pigmented or nonpigmented, and it have a junctional, subepithelial, or compound configuration.

2. The lesion may be found in children.

3. Combined nevi may involve the tarsal conjunctiva.

G. Multifocal blue nevus of the conjunctiva may simulate malignant melanoma.

VI. Congenital melanocytosis (see Table 17.1)

A. Congenital ocular melanocytosis (melanosis oculi; see Fig. 17.6)

1. Probably it is best considered as a diffuse blue nevus of the conjunctiva.

2. The condition is usually unilateral and is mainly present in dark races (blacks and Asians).

3. The lesion is blue or slate-gray from birth, and it does not move with the conjunctiva.

B. Congenital oculodermal melanocytosis (nevus of Ota; see previously in this chapter).

VII. Unusual types of conjunctival nevi

A. Recurrent nevus—recurrence of an incompletely excised nevus

C. Dysplastic nevus (see previously in this chapter)

D. Spindle-cell nevus (Spitz nevus; juvenile melanoma; see previously in this chapter)

E. Balloon cell nevus—probably represents lipidized melanocytes

F. Epithelioid cell nevus—composed entirely of epithelioid melanocytes

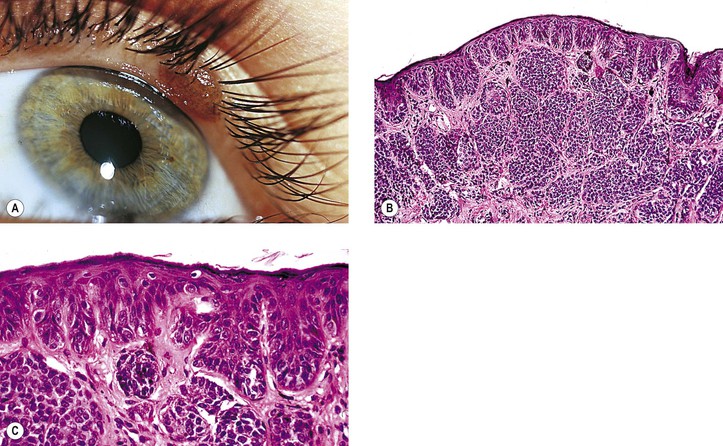

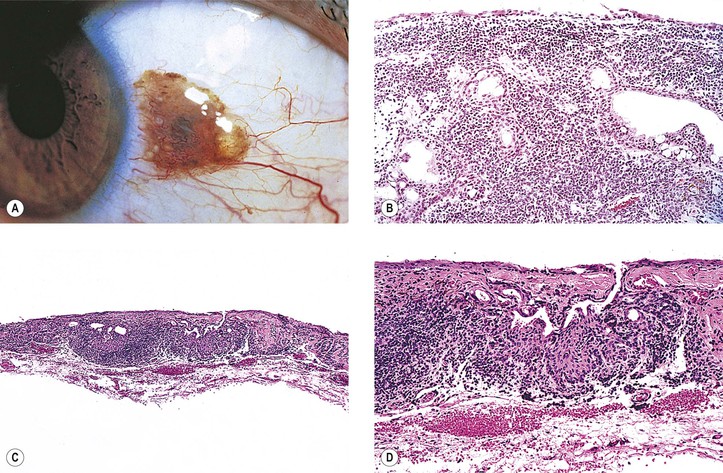

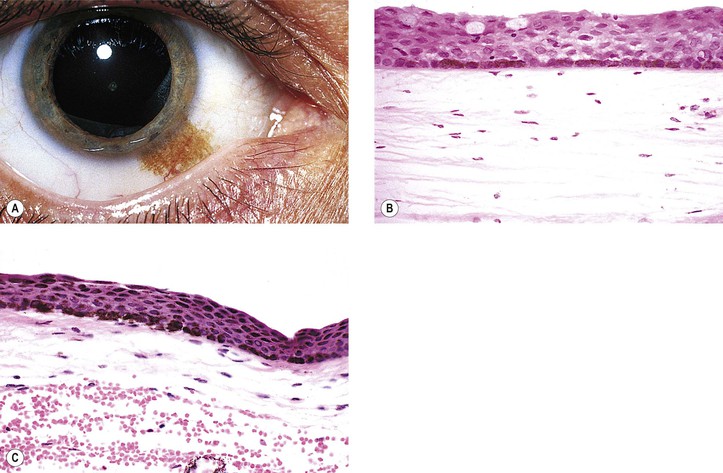

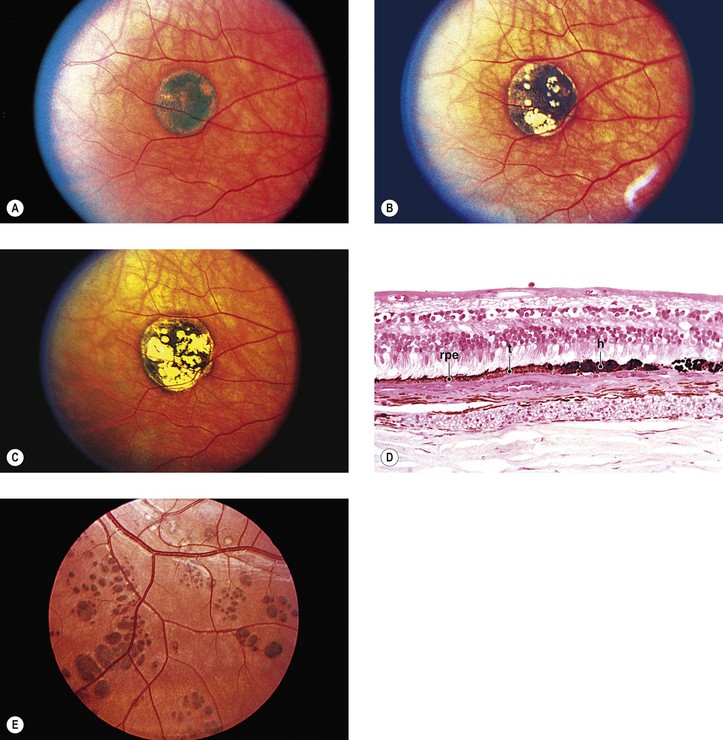

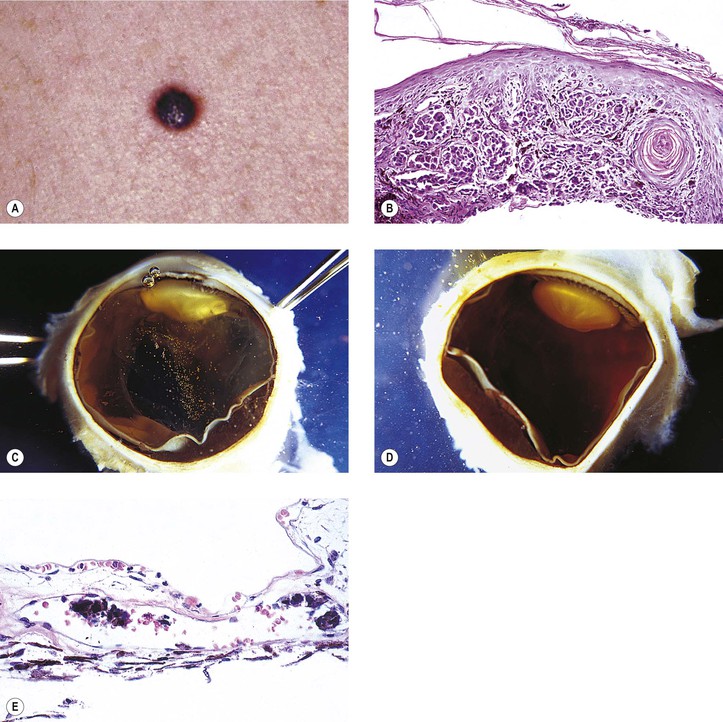

Primary Acquired Melanosis (Figs. 17.13 and 17.14; see also Table 17.1)

B. The mean age at diagnosis is 56 years, with 62% women and 96% whites.

1. Over 10 years, PAM may enlarge in 35% and transform to melanoma in 12%.

2. Progression to melanoma occurs in 0% of lesions lacking atypia and in 13% of PAM with severe atypia.

C. The condition has a variable and protracted course.

2. Approximately 17% become malignant, usually 5–10 years after onset.

D. The age of onset is approximately 40–50 years of age.

E. Rarely, PAM may be associated with malignant melanomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses.

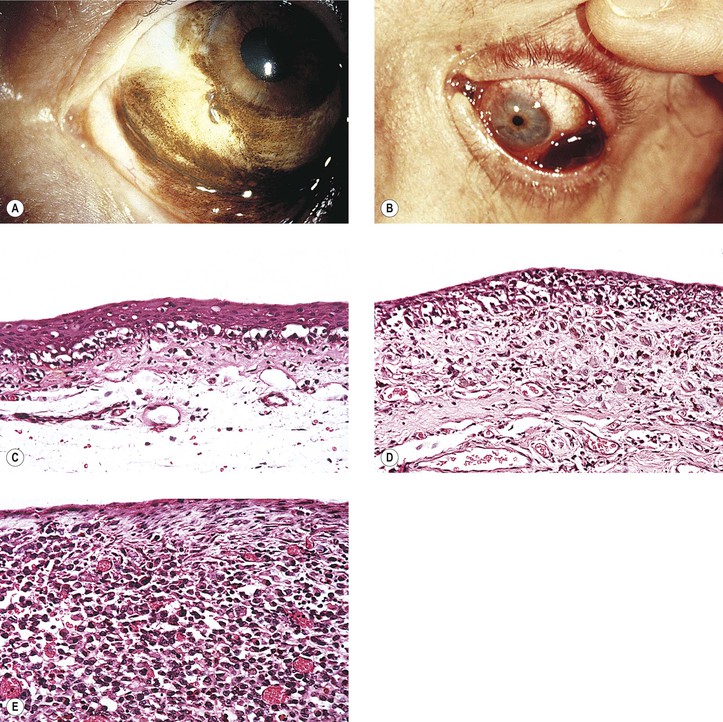

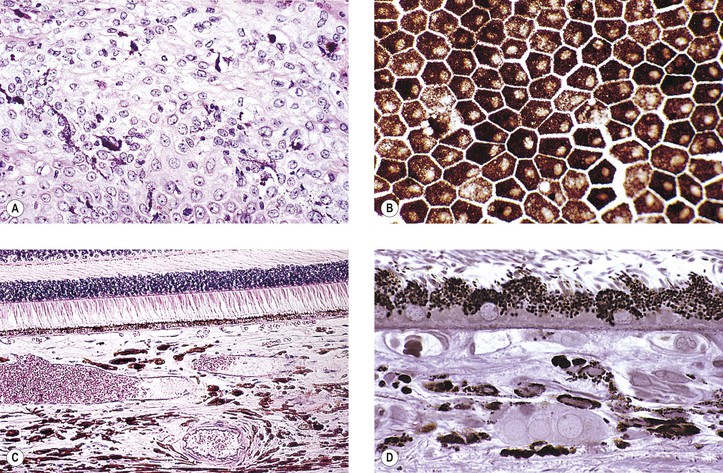

II. Classification of unilateral PAM

A. Stage I: Benign acquired melanosis (precancerous melanosis)

1. Stage IA shows minimal melanocytic hyperplasia.

a. Hyperpigmentation of the epithelium may be the only finding (see Fig. 17.13).

2. Stage IB shows atypical melanocytic hyperplasia.

a. Stage IB1 shows mild to moderately severe atypical melanocytic hyperplasia (see Fig. 17.14C).

2) Histologically, it appears identical to a congenital, conjunctival, junctional nevus.

3. Stage IB2 shows severe atypical melanocytic hyperplasia (“in situ” malignant melanoma).

B. Stage II: Malignant acquired melanosis

1. Stage IIA shows superficially invasive melanoma (tumor thickness <1.5 mm; see Fig. 17.14D).

2. Stage IIB shows significantly invasive melanoma (tumor thickness >1.5 mm; see Fig. 17.14E). The condition in stage IIB is analogous to nodular melanoma of skin (vertical growth phase).

III. Prognosis

A. The probability for development of a stage IA lesion into a malignant melanoma is quite low.

IV. Causes of secondary acquired melanosis

A. Radiation

B. Metabolic disorders (e.g., Addison’s disease and pregnancy)

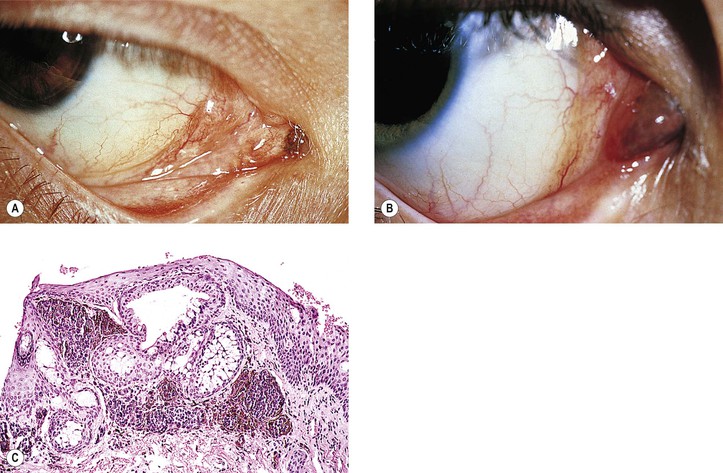

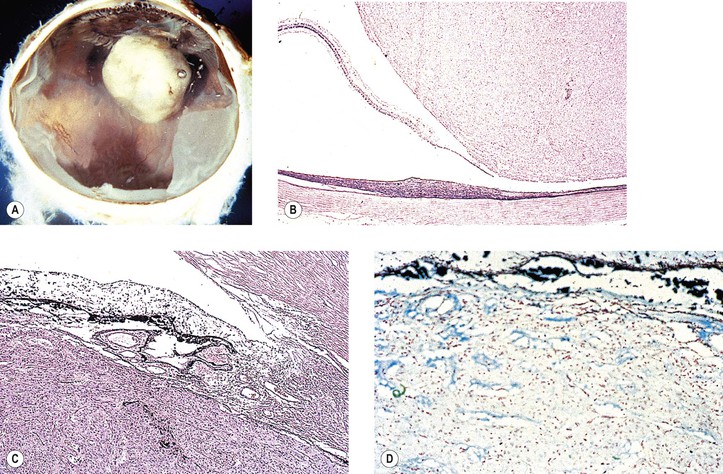

Primary Malignant Melanoma of Conjunctiva (Fig. 17.15; see also Fig. 17.14)

V. It is rare for a melanoma to arise from congenital ocular melanocytosis.

VII. Clinical lack of pigmentation in amelanotic conjunctival melanomas may lead to delay in diagnosis.

VIII. Histology (for histology of PAM, see previously in this chapter)

A. Remnants of a conjunctival nevus may be found in or contiguous to the melanoma.

B. Normal polarity is lost (i.e., deep cells are indistinguishable from superficial cells).

C. The overlying epithelium is invaded.

1. Invasion of the underlying subepithelial tissue occurs concurrently with epithelial invasion.

D. The cells of the neoplasm are atypical.

1. The nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio is increased, and large, abnormal cells may be seen.

2. Mitotic figures may be present, but they are frequently absent.

E. Often, an underlying inflammatory infiltrate of round cells, predominantly lymphocytes, is present.

IX. Secondary—these tumors may arise from intraocular melanomas or may be metastatic.

X. Prognosis

B. If it arises from PAM, the mortality rate is approximately 40%.

C. If it arises de novo or its origin is indeterminate, the mortality rate is approximately 40%.

D. An accurate parameter for predicting prognosis is tumor thickness at the time of extirpation.

1. In general, if the thickness is no greater than 1.5 mm, the prognosis for life is excellent.

2. If the tumor thickness is greater than 1.5 mm, the prognosis for life is extremely grave.

Lesions That May Simulate Primary Conjunctival Nevus or Malignant Melanoma

I. See previous discussion of secondary acquired melanosis in this chapter.

II. See preceding discussion of secondary malignant melanoma of conjunctiva in this chapter.

III. Nevus of sclera—blue nevus, cellular blue nevus, and melanocytoma can occur in the sclera.

A. Blue sclera (see Chapter 8)

B. Ectatic sclera lined by choroid (i.e., staphyloma) may simulate a conjunctival melanoma.

C. Scleromalacia perforans (see Chapter 8)

A. Blood, especially its oxidation product (i.e., hemosiderin), may simulate a conjunctival melanoma.

B. Bile

1. In acute icterus, bilirubin is deposited predominantly in the conjunctiva, not in the sclera.

A. Ochronosis (alkaptonuria; see Chapter 8)

A. Epinephrine plaques (see Chapter 7)

C. Mascara

D. Industrial hazards (e.g., quinones and aniline dyes)

E. Iron

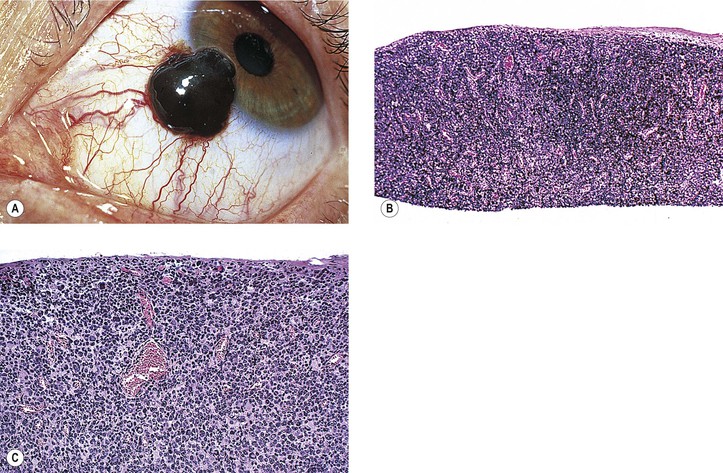

VIII. Pigment spots of the sclera (Fig. 17.16)

A. Pigment spots of the sclera are most commonly found with darkly pigmented irises.

C. They decrease in frequency from superior to inferior to temporal to nasal quadrants.

D. The conjunctiva is freely movable over the pigment spot.

F. Pigment spots of the sclera may be confused with conjunctival nevi, melanomas, and foreign bodies (see Fig. 17.16).

IX. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva may simulate malignant melanoma.

Melanotic Tumors of Pigment Epithelium of Iris, Ciliary Body, and Retina

Reactive Tumors

3. It may result from intrauterine inflammation, trauma, or unknown causes.

5. Histologically, the PE proliferates in cords, tubes, or cystic structures.

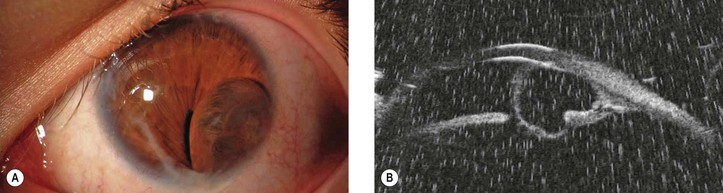

6. Primary cysts of the iris stroma arise within the stroma and are lined by nonkeratinized squamous epithelium and not by iris pigment epithelium (Fig. 17.17). In contrast, as the name implies, cysts of the posterior epithelium are lined by iris pigment epithelium.

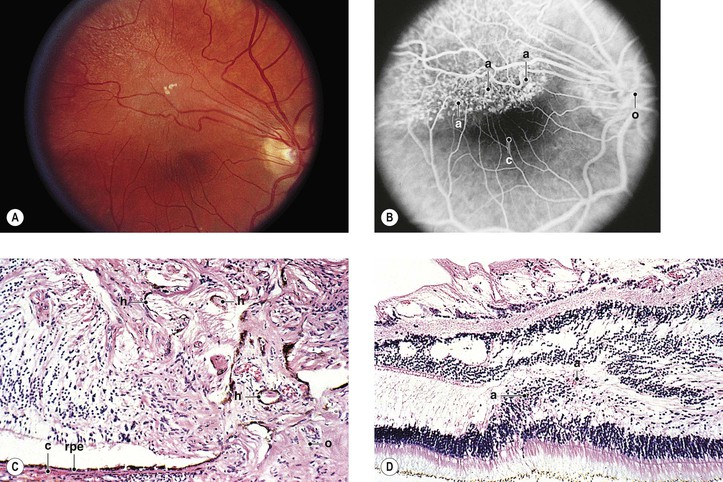

C. Combined hamartoma (idiopathic reactive hyperplasia) of the retina and retinal PE (Fig. 17.18)

1. The lesion is mainly juxtapapillary but may be located peripherally.

2. It is mostly seen in young men between the ages of 20 and 45 years (range, 12–63 years).

3. Clinically, the lesion usually appears as a solitary grayish mass with variable pigmentation and vascularity.

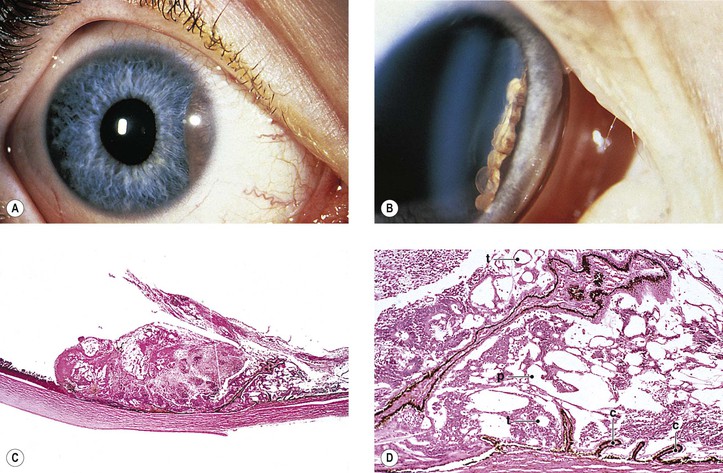

D. Medulloepithelioma (diktyoma)

1. Medulloepithelioma is a unilateral, solitary ocular tumor.

c. The tumor grows slowly and is only locally aggressive.

d. Glaucoma may be the presenting sign.

e. Delay in diagnosis is common.

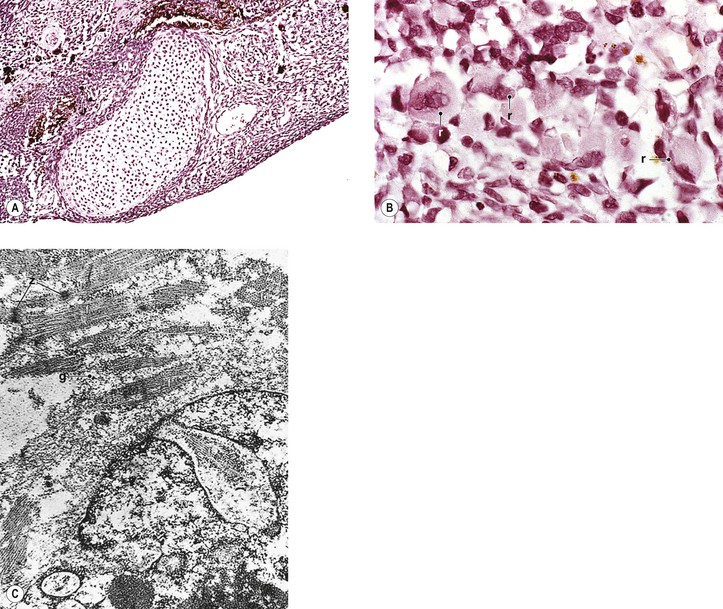

2. Medulloepithelioma (nonteratoid medulloepithelioma) may be benign (Fig. 17.19) or malignant.

3. Heteroplastic elements may be present, in which case the tumor is termed a teratoid medulloepithelioma, benign or malignant (Fig. 17.20).

4. Histologically, nonteratoid medulloepithelioma consists of poorly differentiated neuroectodermal tissue that in some areas resembles embryonic retina.

c. The neuroblastic cells are usually positive for neuron-specific enolase and synaptophysin.

II. Drusen (see Chapter 11)

III. Pseudoneoplastic proliferations

B. Intraneural retinal (usually from RPE)

1. Intraneural retinal reactive RPE proliferations may occur in abiotrophic diseases such as retinitis pigmentosa (see Fig. 11.36).

3. Ringschwiele or demarcation line (see Chapter 11)

C. Intravitreal (usually from ciliary PE or RPE, but may be from iris PE)

1. Intravitreal pseudoneoplastic proliferations of the PE are most common after trauma.

2. They may follow purulent endophthalmitis or other ocular inflammations.

D. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the ciliary body epithelium

May simulate a malignant melanoma

IV. Metaplastic

B. Bone formation (osseous metaplasia; see Fig. 3.14)

2. Intraocular osseous metaplasia is not preceded by cartilage formation.

3. It is common after trauma, long-standing uveitis, and endophthalmitis.

V. Atrophic changes other than as part of age-related macular degeneration.

Nonreactive Tumors

I. Congenital

1. Glioneuromas are rare, benign, choristomatous tumors.

2. Histologically, the tumor is composed of only brain tissue, containing neurons and glial cells and lacking the embryonic retina, ciliary epithelium, and primitive vitreous found in medulloepitheliomas.

Immunohistochemistry shows positivity in the neuronal cells for neuron-specific enolase, synaptophysin, and neurofilaments; in the glial cells for vimentin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and S-100 protein; and in the neuroepithelial cells for cytokeratins, vimentin, neuron-specific enolase, and S-100 protein (suggesting ciliary epithelial origin).

B. Grouped pigmentation (bear tracks; Fig. 17.22; see Chapter 11)

C. RPE hypertrophy (melanotic RPE nevus; benign “melanoma” of the RPE of Reese and Jones; see Fig. 17.22)

D. Congenital hypertrophy of the RPE (CHRPE) presents clinically as a round or oval, jet-black, flat (or slightly elevated) lesion usually surrounded by a halo (due to partial or complete RPE hypopigmentation), most commonly found in the temporal fundus.

5. CHRPE may be associated with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) of the colon and the variant, Gardner’s syndrome.

a. CHRPE is present in 70% of families with FAP.

b. FAP has a 100% incidence of colonic adenocarcinoma if untreated.

8. Hamartomas of the RPE are divided into at least three types: (1) a monolayer of hypertrophic RPE cells (CHRPE), (2) a mound of pigmented cells interposed between Bruch’s membrane and RPE basement membrane, and (3) a small mound of hyperplastic RPE cells (nodular RPE hypertrophy).

a. Hamartomas of the RPE are most helpful in the diagnosis of Gardner’s syndrome.

b. Hamartomas of the RPE are detectable before the development of intestinal polyps.

e. There is no association between CHRPE characteristics and specific FAP variants.

a. The surrounding halo is due to atrophy or loss of pigment from the adjacent RPE or both.

b. Degeneration of the overlying neural retinal photoreceptor cells may be found.

11. Congenital hypertrophy of the RPE can give rise to adenocarcinoma.

Acquired Neoplasms

I. Fuchs’ adenoma (proliferation rather than neoplasm; see Fig. 9.17)

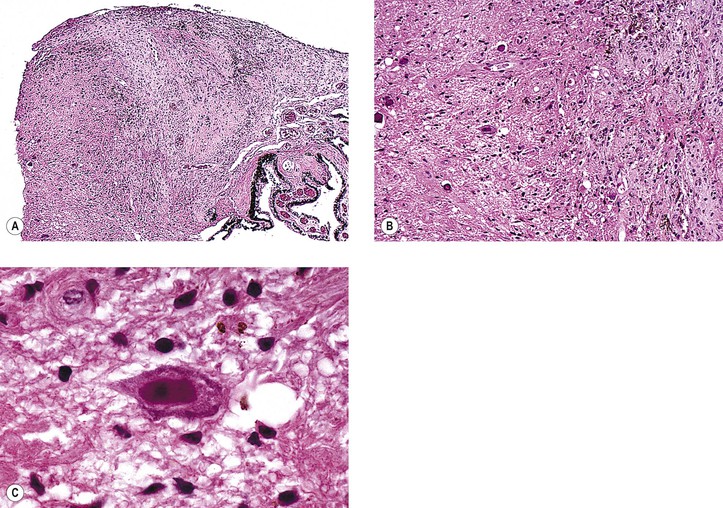

II. Adenoma (epithelioma; Fig. 17.23)

A. Adenomas may arise from the ciliary epithelium or RPE.

D. Histologically, the epithelial cells appear polyhedral and have variable pigmentation.

2. The heavily pigmented cells are frequently vacuolated.

3. Nuclear atypia is common, but mitotic figures are rare.

6. Histologically, adenoma may be difficult to differentiate from reactive proliferations of the PE.

8. Transmission electron microscopy reveals tight junctions between cells.

III. Adenocarcinoma

C. Adenocarcinoma is a histologic diagnosis based on cellular atypia.

IV. Leiomyoepithelioma of iris PE

V. Melanotic neuroectodermal (retinal anlage) tumor of infancy

Melanotic Tumors of the Uvea

Iris

I. Ephelis (freckle; Fig. 17.24)

B. There is no discrete mass or nodule.

II. Nevus (see Fig. 17.24)

C. An increased incidence of iris nevi occurs in people who have neurofibromatosis (see Fig. 2.4) but probably not in those who have ciliary body or choroidal malignant melanomas.

E. An acquired, diffuse nevus of the iris may be associated with the iris nevus syndrome, part of the iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome (see Chapter 16).

III. Heterochromia (Table 17.2)

IV. Malignant melanoma (Figs. 17.25 and 17.26; see also Fig. 16.18)

A. Iris malignant melanomas have no sex predilection; the average age of involvement is 64 years.

B. They are the most common primary malignant neoplasm of the iris and constitute approximately 5–8% of all uveal melanomas; they usually arise from the anterior border layer tissue of the iris (as do iris nevi).