34 Occipital Neuralgia∗

Anatomy

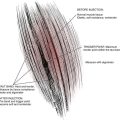

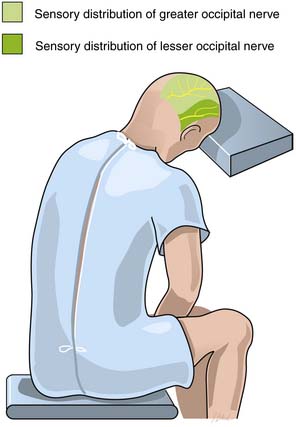

Occipital neuralgia is one type of cervicogenic headache described as pain in the distribution of the greater and/or lesser occipital nerve(s), associated with posterior scalp dysesthesia and/or hyperalgesia. The greater occipital nerve innervates the posterior skull from the suboccipital area to the vertex. It is formed from the medial (sensory) branch of the posterior division of the second cervical nerve.1 It emerges between the atlas and lamina of the axis below the oblique inferior muscle and then ascends obliquely on the latter muscle between it and the semispinalis muscle.1 The course of the greater occipital nerve does not appear to differ in males and females.2

The lesser occipital nerve forms from the medial (sensory) branch of the posterior division of the third cervical nerve, ascends similar to the greater occipital nerve, and pierces the splenius capitis and trapezius muscles just medial to the greater occipital nerve.1,2 It ascends along the scalp to reach the vertex, where it provides sensory fibers to the area of the scalp lateral to the greater occipital nerve. The Occipital neuralgia (for clarity) appears to be more common in females.3

Symptoms

Paroxysmal occipital neuralgia describes pain occurring only in the distribution of the greater occipital nerve. The attacks are unilateral, and the pain is sudden and severe. The pain is described as a lancinating, sharp, throbbing, electric shock-like pain.4–6 The pain may demonstrate a burning characteristic, but this is less common. Although single flashes of pain may occur, multiple attacks are more frequent. The attacks may occur spontaneously or be provoked by specific maneuvers applied to the back of the scalp or neck regions, such as brushing the hair or moving the neck.7

Two broad categories of patients with occipital neuralgia are those with structural pathology and those without apparent etiology.1 Proposed etiologies include myofascial tightening, trauma of C2 nerve root (whiplash injury), prior skull or suboccipital surgery, other type of nerve entrapment, idiopathic causes, hypertrophied atlantoepistrophic (C1-2) ligament, sustained neck muscle contractions, or spondylosis of the cervical facet joints (particularly C2-3 and C3-4).4,6,8–11 Most patients with occipital neuralgia do not have discernible lesions.1

Acute continuous occipital neuralgia often has an underlying etiology. The attacks last for many hours and are typically devoid of radiating symptoms (e.g., trigger zones to the face). The entire episode of neuralgia will continue up to 2 weeks before remission. Exposure to cold is a common trigger.7

In chronic continuous occipital neuralgia, the patient may experience painful attacks that last for days to weeks. These attacks are generally accompanied by localized spasm of the cervical or occipital muscles. The reported pain originates in the suboccipital region up to the vertex and radiates to the frontotemporal region. Radiation to the orbital region is also common. Sensory triggers to the face or skull can initiate a painful episode. Similarly, pain may increase with pressure of the head on a pillow. Prolonged abnormal fixed postures that occur in reading or sleeping positions and hyperextension or rotation of the head to the involved side may provoke the pain. The pain may be bilateral, although the unilateral pattern is more common. Often, a previous history of cervical or occipital trauma or arthritic disease of the cervical spine is obtained. Occasionally, patients may report other autonomic symptoms concurrently such as nausea, vomiting, photophobia, diplopia, ocular and nasal congestion, tinnitus, and vertigo.7 Severe ocular pain has also been described, as well as symptoms in other distributions of the trigeminal nerve.8,12–14 Convergence of sensory input from the upper cervical nerve roots into the trigeminal nucleus may explain this phenomenon.11

Entrapment of the nerve near the cervical spine may result in increased symptoms during flexion, extension, or rotation of the head and neck. Compression of the skull on the neck (Spurling’s maneuver), especially with extension and rotation of the neck to the affected side, may reproduce or increase the patient’s pain if cervical degenerative disease is the cause of the neuralgia.7 Pressure over both the occipital nerves along their course in the neck and occiput, or pressure on the C2-3 or C3-4 facet joints should cause an exacerbation of pain in such patients, at least when the headache is present. Even if the actual pathology is in the cervical spine, tenderness over the occipital nerve at the superior nuchal line is usually present.

(From Waldman SD: Greater and lesser occipital nerve block. In Waldman SD (ed): Atlas of Interventional Pain Management, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2004, pp 23-26.)29

The diagnosis of occipital neuralgia is generally made clinically, based on history and physical examination. Imaging may help confirm the diagnosis when there is an anatomic cause such as cervical spondylosis. Diagnostic local anesthetic nerve blocks may be required to obtain a definitive diagnosis; these blocks are done with or without the addition of corticosteroid.1,4,11 The relief of pain after a diagnostic local anesthetic block of the greater/lesser occipital nerves is generally confirmatory of the diagnosis of occipital neuralgia.

Indications for Nerve Block

Appropriate treatment interventions for pain from occipital neuralgia may include oral medications, heat/cold therapy, massage, avoidance of excessive cervical spine flexion/extension or rotation, acupuncture, application of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), physical therapy, nerve block and—in rare cases—neuromodulation/nerve stimulators or surgery.15–19

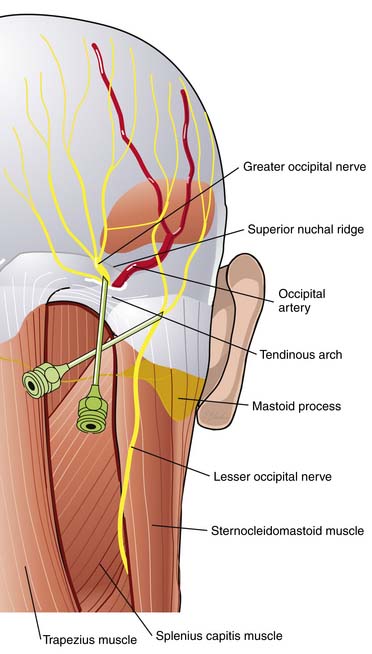

Blockade of the greater or lesser occipital nerve with a local anesthetic is diagnostic and therapeutic (Fig. 34-2). Pain relief can vary from hours to months. In general, at least 50% of patients will experience more than 1 week of relief after one injection. Case reports of isolated pain relief for greater than 17 months have been achieved after a series of five blocks.6 The addition of a corticosteroid preparation is controversial, but it may provide additional benefit.3

Figure 34-2 Corticosteroid/anesthetic nerve block. The patient is placed in a sitting position with the cervical spine flexed and the forehead on a padded bedside table. A total of 8 mL of local anesthetic is drawn up in a 12 mL sterile syringe. A total of 80 mg of depot-steroid is added to the local anesthetic with the first block and 40 mg with subsequent blocks. The occipital artery is palpated at the level of the superior nuchal ridge. After preparation of the skin with antiseptic solution, a 22 or 25 gauge, 1.5-inch needle is inserted just medial to the artery and is advanced perpendicularly until the needle approaches the periosteum of the underlying occipital bone. A paresthesia may be encountered. The needle is then redirected superiorly, and after gentle aspiration 5 mL of solution is injected in a fanlike distribution with care being taken to avoid the foramen magnum. (From Waldman SD: Greater and lesser occipital nerve block. In Waldman SD (ed): Atlas of Interventional Pain Management, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2004, pp 23-26.)29

Botulinum toxin block. The same procedure is used with 50-150 units of botulinum toxin A.30

(From Kapural L, Stillman M, Kapural M, et al: Botulinum toxin occipital nerve block for the treatment of severe occipital neuralgia: A case series. Pain Pract. 7:337-340, 2007.)

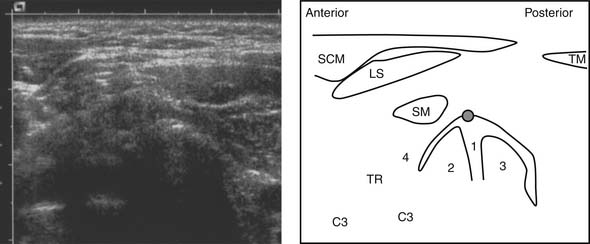

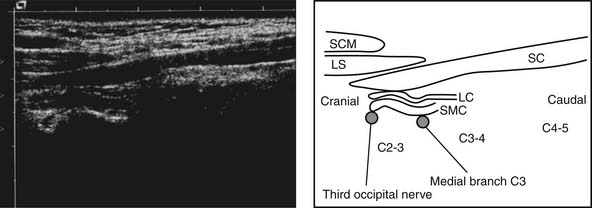

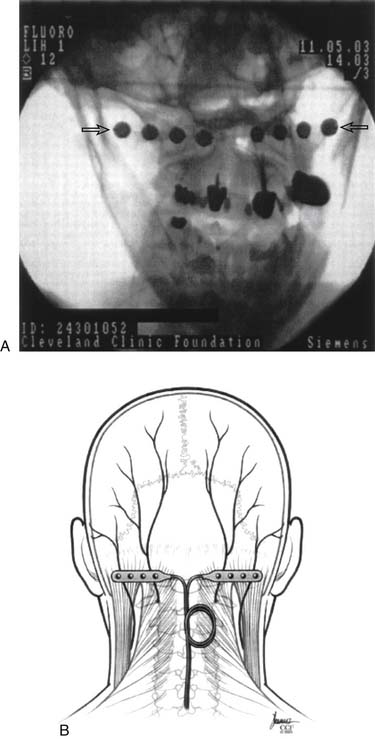

Blockade of the third occipital nerve (formed by the medial or sensory branch of C3) with local anesthetic alone or with corticosteroid as it crosses the C2-3 zygapophysial joint can also be diagnostic and therapeutic for occipital neuralgia, especially where blockade of the greater/lesser occipital nerve does not provide sustained relief, or where there is both spondylitic neck pain and symptoms of occipital neuralgia.20 Both fluoroscopically and ultrasound-guided techniques have been described for this (Figs. 34-4 to 34-6).20,21 If blockade of this nerve(s) provides only temporary relief, radiofrequency lesioning (RFL) can be performed of the third occipital nerve and C3 medial branch to provide long-lasting relief of occipital neuralgia.22,23

Potential Treatment Complications

Surgery with dorsal rhizotomy of C1-4, has been described with about 71% to 77% of patients reporting significant benefit.6,24–26 Before dorsal rhizotomy, local anesthetic blockade of the suspected medial (sensory) branches should be performed for diagnostic purposes. Surgical neurolysis with excision of the greater and/or lesser occipital nerve has been described with 80.5% of patients experiencing 50% or greater pain relief.27 Botulinum toxin A injection into the greater occipital nerve has also been described.3,28

1. Loeser J.D., editor. Bonica’s Management of Pain. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

2. Natsis K., Baraliakos X., Appell H.J., et al. The course of the greater occipital nerve in the suboccipital region: A proposal for setting landmarks for local anesthesia in patients with occipital neuralgia. Clin Anat. 2006;19:332-336.

3. Volcy M., Tepper S.J., Rapoport A.M., et al. Botulinum toxin A for the treatment of greater occipital neuralgia and trigeminal neuralgia: A case report with pathophysiological considerations. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:336-340.

4. Slavin K.V., Nersesyan H., Wess C. Peripheral neurostimulation for treatment of intractable occipital neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:112-119.

5. Kapural L., Mekhail N., Hayek S.M., et al. Occipital nerve electrical stimulation via the midline approach and subcutaneous surgical leads for treatment of severe occipital neuralgia: A pilot study. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:171-174.

6. Kapoor V., Rothfus W.E., Grahovac S.Z., et al. Refractory occipital neuralgia: Preoperative assessment with CT-guided nerve block prior to dorsal cervical rhizotomy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:2105-2110.

7. Rizzo T.D. Occipital neuralgia. In: Frontera W.R., Silver J.K., editors. Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 2001.

8. Hammond S.R., Danta G. Occipital neuralgia. Clin Exp Neurol. 1978;15:258-270.

9. Star M.J., Curd J.G., Thorne R.P. Atlantoaxial lateral mass osteoarthritis. A frequently overlooked cause of severe occipitocervical pain. Spine. 1992;17(Suppl 6):S71-S76.

10. Kuhn W.F., Kuhn S.C., Gilberstadt H. Occipital neuralgias: Clinical recognition of a complicated headache. A case series and literature review. J Orofac Pain. 1997;11:158-165.

11. Hecht J.S. Occipital nerve blocks in postconcussive headaches: A retrospective review and report of ten patients. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2004;19:58-71.

12. Mason J.O .III, Katz B., Greene H.H. Severe ocular pain secondary to occipital neuralgia following vitrectomy surgery. Retina. 2004;24:458-459.

13. Knox D.L., Mustonen E. Greater occipital neuralgia: An ocular pain syndrome with multiple etiologies. Trans Sect Ophthalmol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 79, 1975. OP513-9

14. Fredriksen T.A., Hovdal H., Sjaastad O. “Cervicogenic headache”: clinical manifestation. Cephalalgia. 1987;7:147-160.

15. Franzini A., Leone M., Messina G., et al. Neuromodulation in treatment of refractory headaches. Neurol Sci. 2008;1:S65-S68.

16. Amin S., Buvanendran A., Park K.S., et al. Peripheral nerve stimulator for the treatment of supraorbital neuralgia: A retrospective case series. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:355-359.

17. Gille O., Lavignolle B., Vital J.M. Surgical treatment of greater occipital neuralgia by neurolysis of the greater occipital nerve and sectioning of the inferior oblique muscle. Spine. 2004;29:828-832.

18. Rasskazoff S., Kaufmann A.M. Ventrolateral partial dorsal root entry zone rhizotomy for occipital neuralgia. Pain Res Manag. 2005;10:43-45.

19. Stojanovic M.P. Stimulation methods for neuropathic pain control. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2001;5:130-137.

20. Eichenberger U., Greher M., Kapral S., et al. Sonographic visualization and ultrasound-guided block of the third occipital nerve: Prospective for a new method to diagnose C2-C3 zygapophysial joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:303-308.

21. Bogduk N. The neck and headaches. Neurol Clin. 2004;22:151-171.

22. Lord S.M., Barnsley L., Wallis B.J., et al. Percutaneous radio-frequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1721-1726.

23. McDonald G.J., Lord S.M., Bogduk N. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with cervical radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic neck pain. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:61-67.

24. Koch D., Wakhloo A.K. CT-guided chemical rhizotomy of the C1 root for occipital neuralgia. Neuroradiology. 1992;34:451-452.

25. Ehni G., Benner B. Occipital neuralgia and the C1-2 arthrosis syndrome. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:961-965.

26. Dubuisson D. Treatment of occipital neuralgia by partial posterior rhizotomy at C1-3. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:581-586.

27. Ducic I., Hartmann E.C., Larson E.E. Indications and outcomes for surgical treatment of patients with chronic migraine headaches caused by occipital neuralgia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1453-1461.

28. Martelletti P., van Suijlekom H. Cervicogenic headache: Practical approaches to therapy. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:793-805.

29. Waldman S.D. Greater and lesser occipital nerve block. In: Waldman S.D., editor. Atlas of Interventional Pain Management. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:23-26.

30. Kapural L., Stillman M., Kapural M. Botulinum toxin occipital nerve block for the treatment of severe occipital neuralgia: A case series. Pain Pract. 2007;7:337-740.