Obstructive sleep apnea

Epidemiology

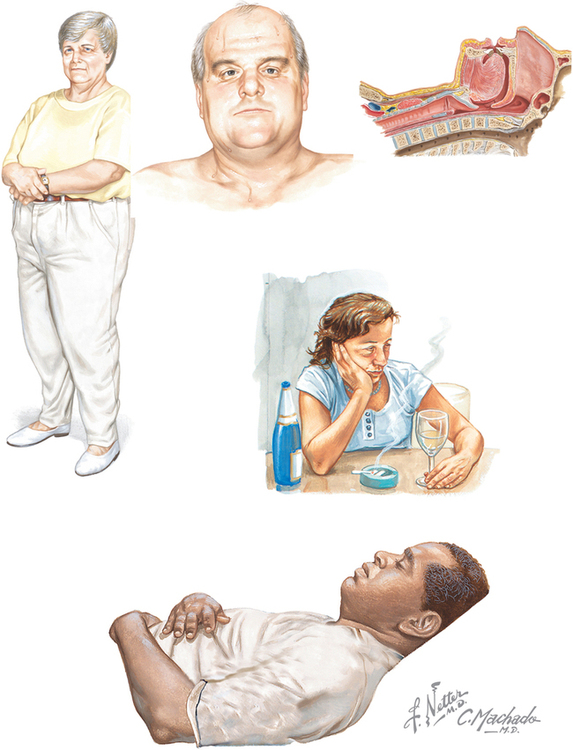

The prevalence of OSA is estimated at 3% to 7% of adult men and 2% to 5% of adult women. Some groups of people have a higher disease prevalence, including older adults and those who are overweight (Figure 108-1). Most OSA remains undiagnosed and, as the population ages and the obesity epidemic explodes, a surge in disease prevalence is expected.

Pathophysiology

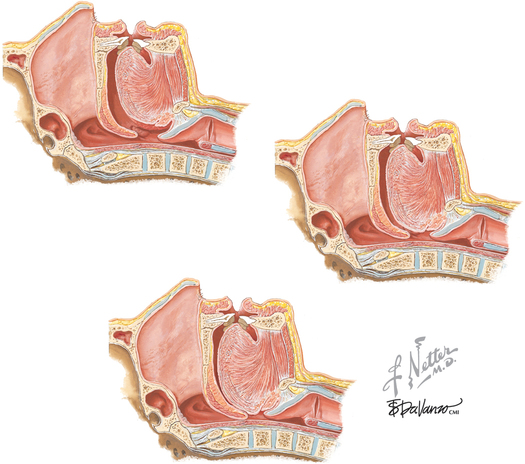

The upper airway from the hard palate to the larynx has evolved as a multipurpose complex structure. Its ability to collapse and change shape is essential for the functions of breathing, swallowing, and speaking. The airways of patients with OSA are narrow and more prone to collapse (Figure 108-2). These individuals are more dependent on increased tone of the airway dilator muscles during wakefulness to maintain airway patency. Decreased tone at the onset of sleep in healthy patients and those with OSA causes breathing instability. Patients who are highly dependent on increased muscle tone during wakefulness are much more vulnerable to airway obstruction during the transition from wakefulness to sleep. Arousal from sleep helps the patient restore normal respiratory patterns, but the end result is poor-quality fragmented sleep.

Obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, cardiovascular risk, and metabolic syndrome

The patient with OSA who presents to the operating room has more than a single condition. These patients have multiple intertwined comorbid conditions that make their care complicated to manage. Obesity, often an accompaniment to OSA, presents the anesthesia provider’s first set of challenges. Deposition of fat in the pharyngeal tissues exacerbates the underlying narrowness and collapsibility of the pharyngeal airway. Obese patients also accumulate more visceral fat, which appears to affect the severity of the OSA. Symptom severity correlates with weight loss and gain. In the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study, the authors demonstrated that a 10% gain in weight in patients with OSA led to a 32% increase in the number of apneas and hypopneas experienced per hour of sleep (i.e., the apnea-hypopnea index, or AHI; Table 108-1). A modest 10% decrease in weight led to a 26% improvement in the AHI. Weight loss results in a dose-dependent decrease in the severity of the syndrome.

Table 108-1

Severity of Obstructive Sleep Apnea

| Severity Category | AHI* |

| None | 0-5 |

| Mild | 6-20 |

| Moderate | 21-40 |

| Severe | >40 |

*The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) is number of apneas plus hypopneas per hour of sleep.

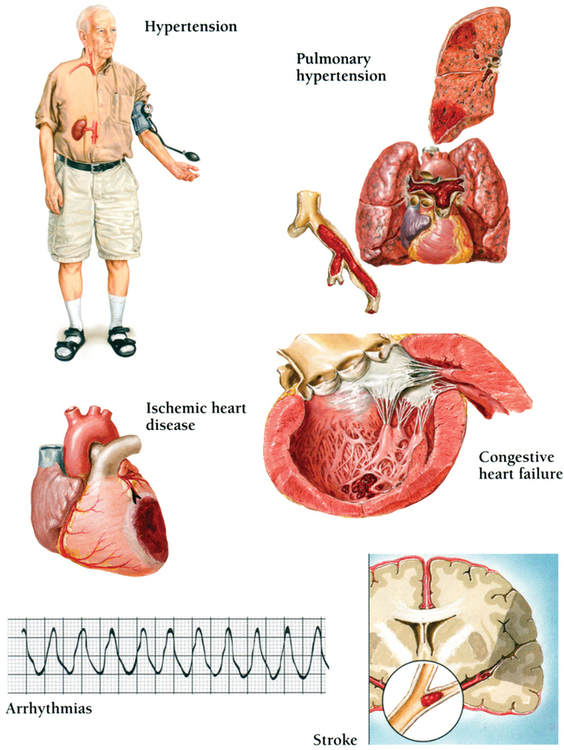

OSA and obesity also play a significant role in cardiovascular morbidity. Obesity increases the risk of hypertension, heart failure, stroke, and coronary heart disease (Figure 108-3). OSA independently increases the risk of cardiovascular disease regardless of age, sex, or comorbid conditions such as tobacco use, alcohol use, diabetes, and obesity. The Sleep Heart Health Study data indicate that the odds ratios of atrial fibrillation, coronary heart disease, and tachycardia are all elevated in patients with OSA. The mechanism of increased cardiovascular risk in patients with OSA has not been entirely delineated but appears to involve the sustained sympathetic activation, oxidative stress, and resulting vascular inflammation that occur with the repetitive episodes of hypercarbia and hypoxia. These patients have higher levels of inflammatory mediators such as C-reactive protein and interleukin 6 in conjunction with elevated levels of endothelin and decreased levels of nitric oxide. Treatment of OSA with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) improves hypertension, decreases levels of inflammatory mediators, and in some patients with dyslipidemia, promotes regression of atherogenic plaque.

Anesthetic management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea

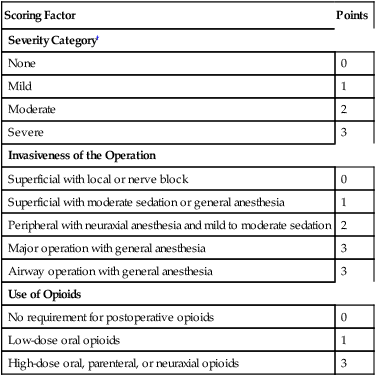

The patient with OSA presents a number of anesthetic challenges. The first critical step is identification of the disease. Upward of 80% to 90% of patients with OSA have not had the syndrome diagnosed. Any patient who presents with obesity, hypertension, or any of the components of metabolic syndrome should be considered at risk for having OSA, and, therefore, the anesthesia provider should perform a detailed history, including questioning of the sleep partner, using the STOP acronym to identify patients with OSA (Snoring, Tiredness, Observed apnea, high blood Pressure). Often, patients are completely unaware of the disease and require education. A simple identification questionnaire and scoring system can help identify at-risk patients, assess perioperative risk, and guide clinical decision making (Box 108-1 and Table 108-2).

Table 108-2

Obstructive Sleep Apnea Scoring System*

| Scoring Factor | Points |

| Severity Category† | |

| None | 0 |

| Mild | 1 |

| Moderate | 2 |

| Severe | 3 |

| Invasiveness of the Operation | |

| Superficial with local or nerve block | 0 |

| Superficial with moderate sedation or general anesthesia | 1 |

| Peripheral with neuraxial anesthesia and mild to moderate sedation | 2 |

| Major operation with general anesthesia | 3 |

| Airway operation with general anesthesia | 3 |

| Use of Opioids | |

| No requirement for postoperative opioids | 0 |

| Low-dose oral opioids | 1 |

| High-dose oral, parenteral, or neuraxial opioids | 3 |

*Patients with a score of 5 or higher may be at significantly increased risk for developing perioperative complications associated with obstructive sleep apnea.

†Subtract 1 point if the patient has been fitted for and uses continuous positive airway pressure via a mask.

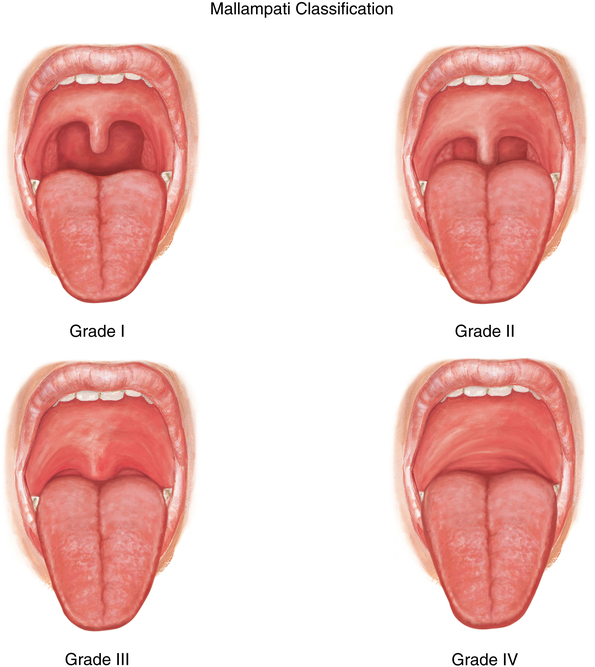

When general anesthesia is chosen, many issues should be considered. The underlying pathophysiology of OSA also makes these patients at high risk for having difficult airway management. Patients older than 55 years, who have a body mass index of more than 35 kg/m2, or who snore are at risk for having difficult mask ventilation. Patients with a Mallampati score of 3 or 4, whose neck circumference is greater than 17 inches, who are unable to protrude the jaw, or who have significant submandibular tissue are at risk for experiencing a difficult intubation (Figure 108-4). These patients are also prone to developing rapid and severe desaturations resulting from higher metabolic demand, decreased functional reserve capacity, and increased collapsibility and obstruction of the pharyngeal airway.

The anesthetic plan must also take into account the significant morbidity and possible fatality associated with OSA. Patients who score a 5 or higher using the criteria listed in Table 108-2 may be at significant risk of developing postoperative airway obstruction or apnea or of dying. If the anesthetic cannot be managed with local anesthesia or regional anesthesia with minimal sedation, the risk of postoperative complications is higher. Patients who have been treated with CPAP should resume therapy in the postanesthesia care unit. Some patients will require initiation of CPAP while in the hospital. This can be accomplished in consultation with the respiratory therapy department. Patients with OSA, particularly those at high risk, should be observed overnight with continuous pulse oximetry and capnometry. The use of opioids should be minimized, and nonopioid adjuncts should be utilized, including a continuous peripheral nerve block via a catheter, an epidural infusion of a local anesthetic agent, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and acetaminophen.