Chapter 41 Nutritional Requirements

Dietary Reference Intakes

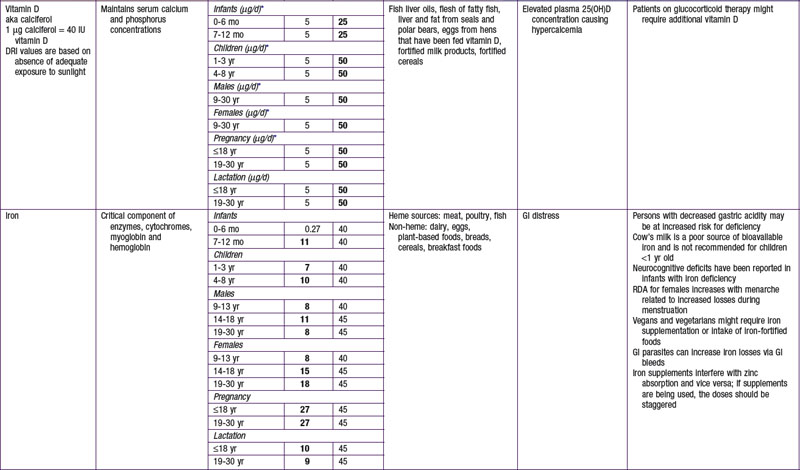

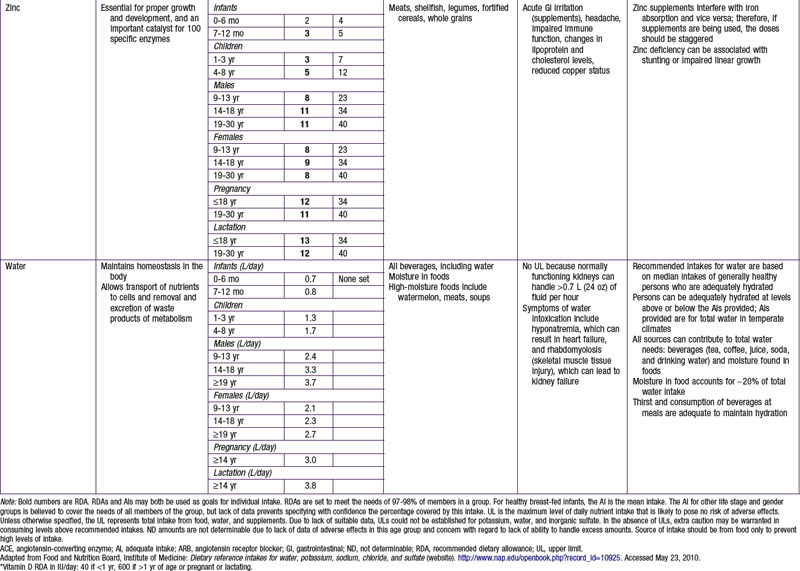

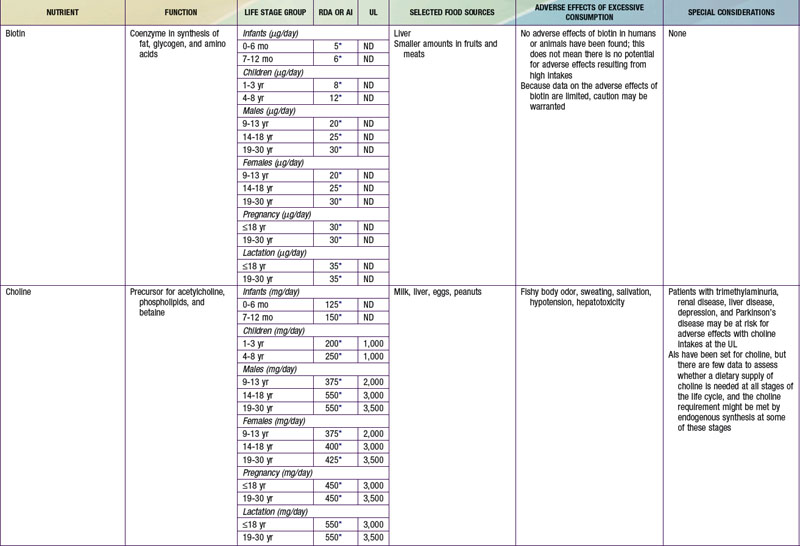

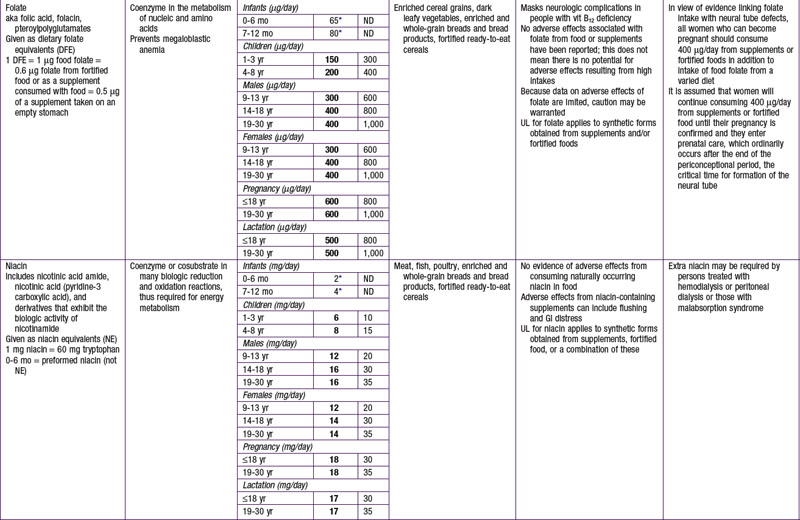

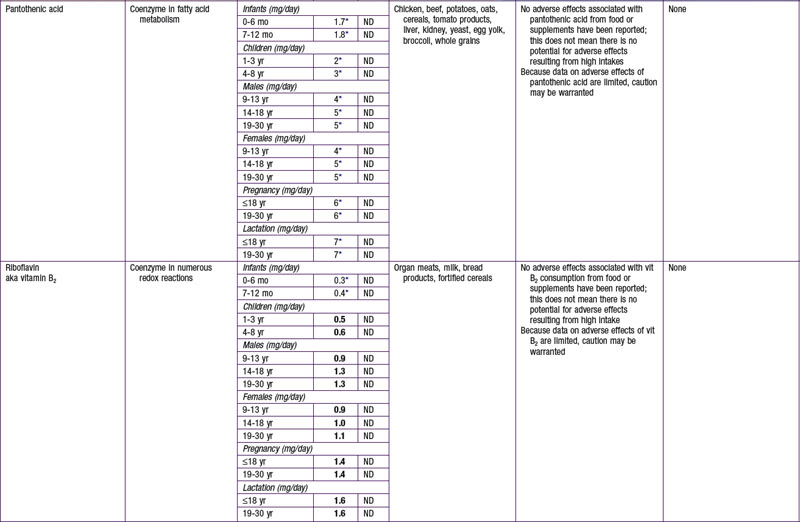

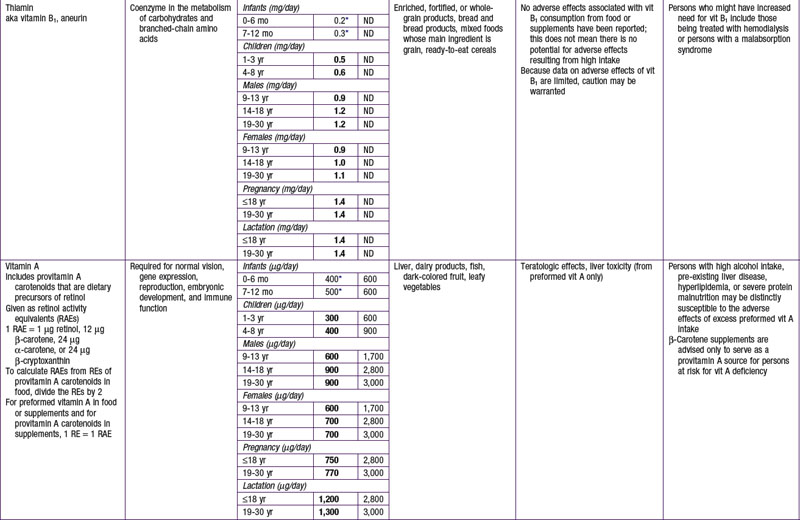

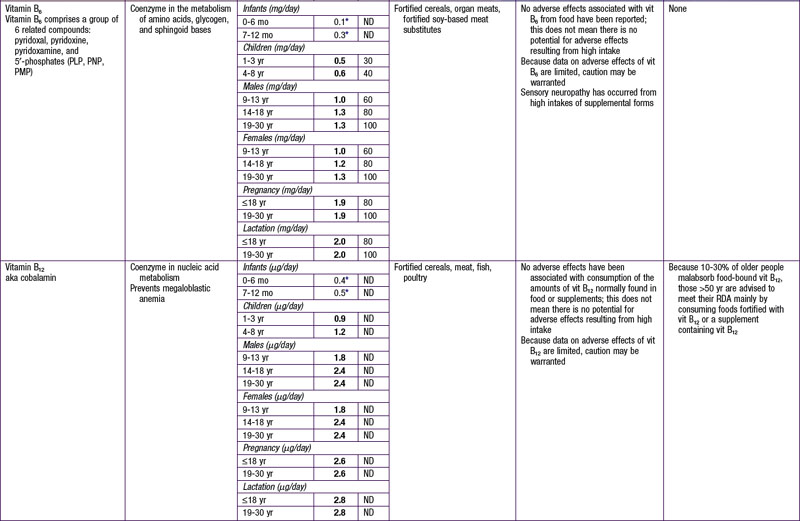

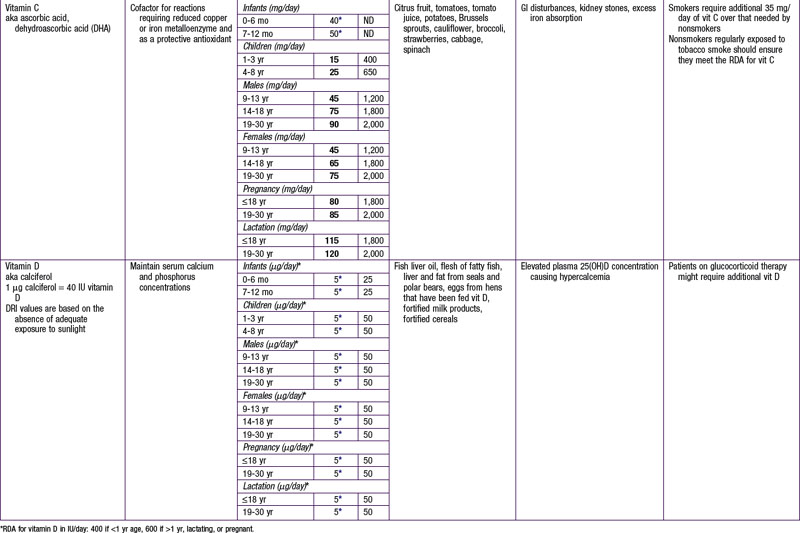

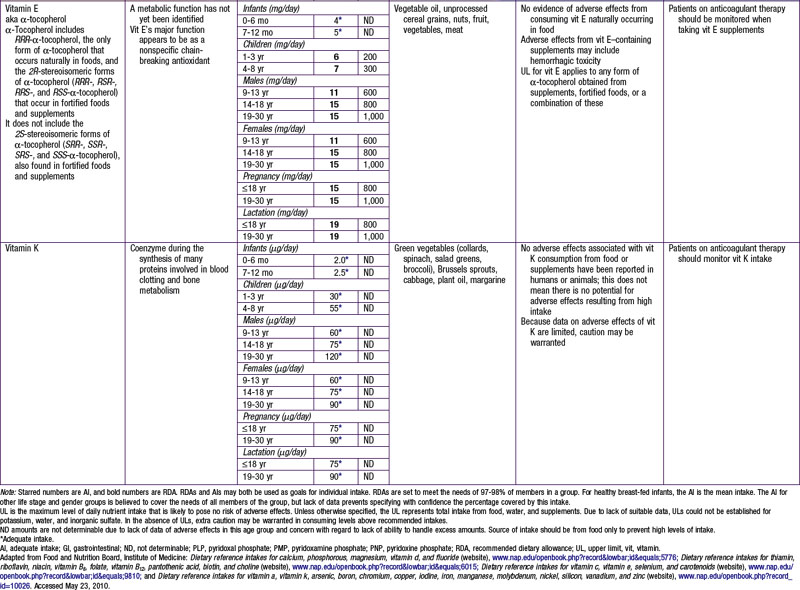

The dietary reference intake (DRI) has been established for most nutrients by the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine using a rigorous process of scientific evidence evaluation (Tables 41-1 to 41-8). The DRI provides guidance as to nutrient needs for individuals and groups across different life stages and by sex. The DRI replaces the former recommended dietary allowances (RDA).

Table 41-1 DEFINING THE DIETARY REFERENCE INTAKES

| INFANTS AND YOUNG CHILDREN: EER (kcal/day) = TEE + ED | |

| 0-3 mo | EER = (89 × weight [kg] − 100) + 175 |

| 4-6 mo | EER = (89 × weight [kg] − 100) + 56 |

| 7-12 ms | EER = (89 × weight [kg] − 100) + 22 |

| 13-35 mo | EER = (89 × weight [kg] − 100) + 20 |

| CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS 3-18 yr: EER (kcal/day) = TEE + ED | |

| Boys | |

| 3-8 yr | EER = 88.5 − (61.9 × age [yr] + PA × [(26.7 × weight [kg] + (903 × height [m])] +20 |

| 9-18 yr | EER = 88.5 − (61.9 × age [yr] + PA × [(26.7 × weight [kg] + (903 × height [m])] +25 |

| Girls | |

| 3-8 yr | EER = 135.3 − (30.8 × age [yr] + PA [(10 × weight [kg] + (934 × height [m])] + 20 |

| 9-18 yr | EER = 135.3 − (30.8 × age [yr] + PA [(10 × weight [kg] + (934 × height [m])] + 25 |

ED, energy deposition; EER, estimated energy requirement; PA, physical activity quotient; TEE, total energy expenditure.

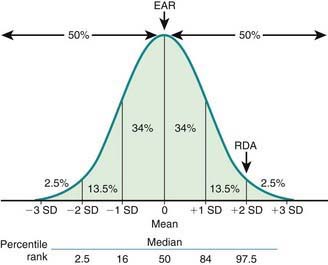

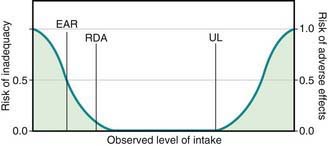

Key DRI concepts include the estimated average requirement (EAR), the recommended dietary allowance (RDA), and the tolerable upper limit of intake (UL) (Fig. 41-1). The EAR is the average daily nutrient intake level estimated to meet the requirements for 50% of the population, assuming normal distribution; the RDA is an estimate of the daily average nutrient intake to meet the nutritional needs of >97% of the individuals in a population, and it can be used as a guideline for individuals to avoid deficiency in the population. When an EAR cannot be derived, an RDA cannot be calculated; therefore, an adequate intake (AI) is developed as a guideline for individuals based on the best available data and scientific consensus. The UL denotes the highest average daily intake at which no adverse health effects are associated for almost all individuals in a particular group. The relationships among EAR, RDA, and UL are characterized in Figure 41-2.

Energy

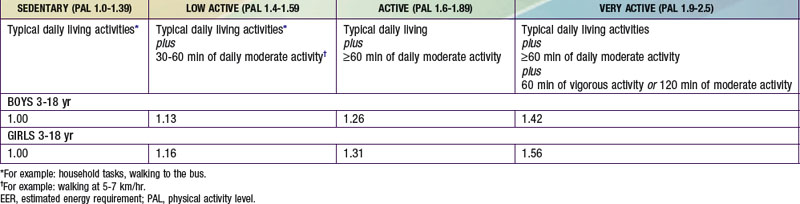

The estimated energy requirement (EER) is the average dietary energy intake predicted to maintain energy balance in a healthy individual of a defined group. The EER accounts for age, gender, weight, stature, and physical activity level (PAL) (see Tables 41-2 and 41-3). The Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the DRI recommend 60 min of moderately intense daily activity for children >2 yr of age to maintain a healthy weight and to prevent or delay progression of chronic noncommunicable diseases such as obesity and cardiovascular disease. The EER was determined based on empirical research in healthy persons at different physical activity levels, including levels different from the recommended levels. They do not necessarily apply to children with acute or chronic diseases. EER is estimated by equations that account for total energy expenditure as well as energy deposition for healthy growth. Note that the EER for infants, relative to body weight, are approximately twice those for adults, due to the increased metabolic rate and requirements for weight maintenance and tissue accretion affecting growth.

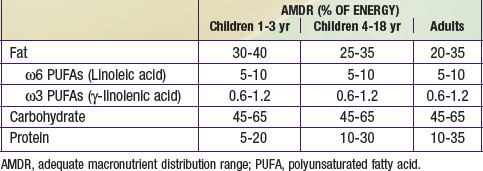

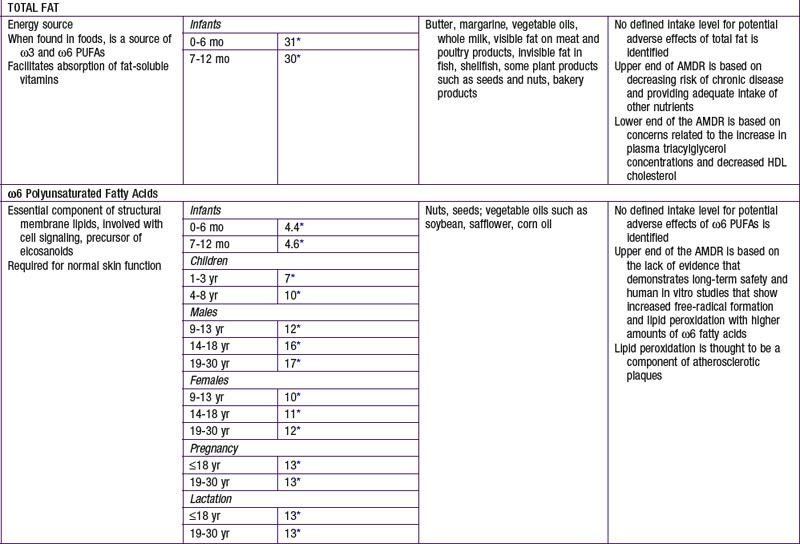

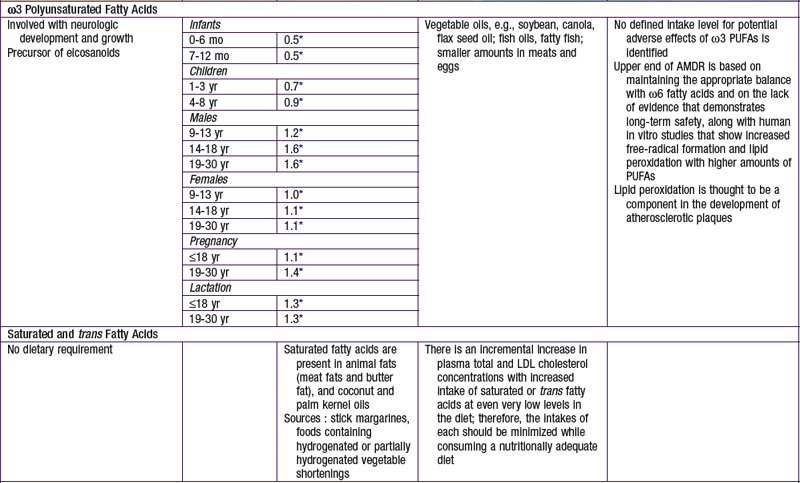

The nutrients that provide energy intake in the child’s diet are fats (∼ 9 kcal/g), carbohydrates (∼ 4 kcal/g), and proteins (∼ 4 kcal/g). They are referred to as macronutrients. Alcohol intake can also contribute to energy intake (∼ 7 kcal/g). The EER does not specify the relative energy contributions of carbohydrates, fats, or proteins. Once the minimal intakes of each of the respective macronutrients are attained to meet physiologic requirements and to achieve adequacy (sufficient protein intake to meet specific amino acid requirements), the remainder of the intake is used to meet energy requirements with some degrees of freedom and interchangeability among fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. This forms the basis for the acceptable macronutrient distribution ranges (AMDR) (see Table 41-4), expressed as a function of total energy intake. In the following sections, each macronutrient is reviewed.

Protein

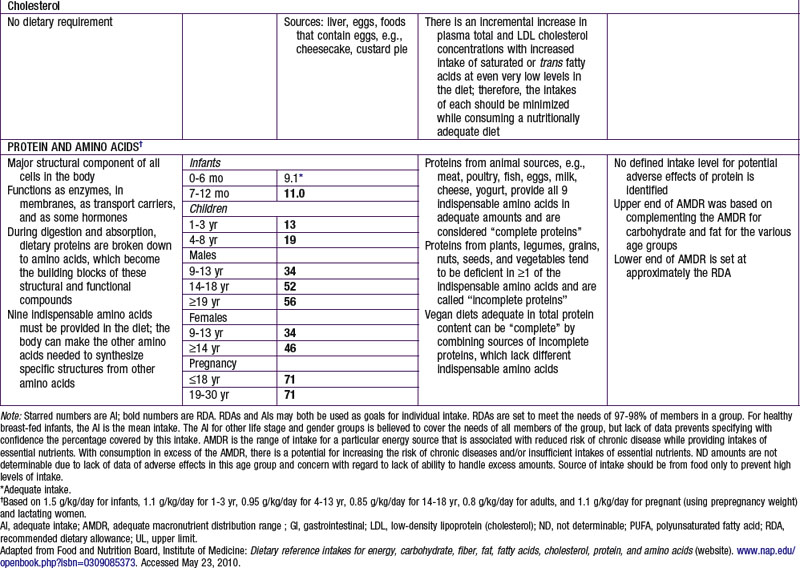

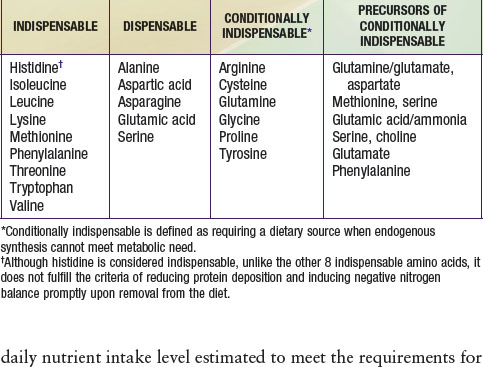

Proteins and amino acids have structural and functional roles in every cell in the body. Proteins also provide about 4 kcal/g (see Table 41-4 for the AMDR). Dietary protein requirements are determined by nitrogen balance studies and are used to determine the EAR and DRI for various age groups.

DRI for protein is provided in Table 41-5. Specific recommendations for appropriate dietary protein sources to meet indispensable amino acid requirements are available for groups adopting specific diets, such as vegetarians and vegans. Use of a variety of food sources to provide all of the required amino acids is a strategy advocated for vegetarians and vegans. A UL for protein has not been set per se, but excessive protein intake may be related to increased risk for gout in some patients. Intake of proteins or specific amino acids needs to be limited in some health conditions, such as renal disease and several rare metabolic diseases in which specific amino acids can be toxic. Specialized medical and nutritional care should be provided for these patients.

Carbohydrates

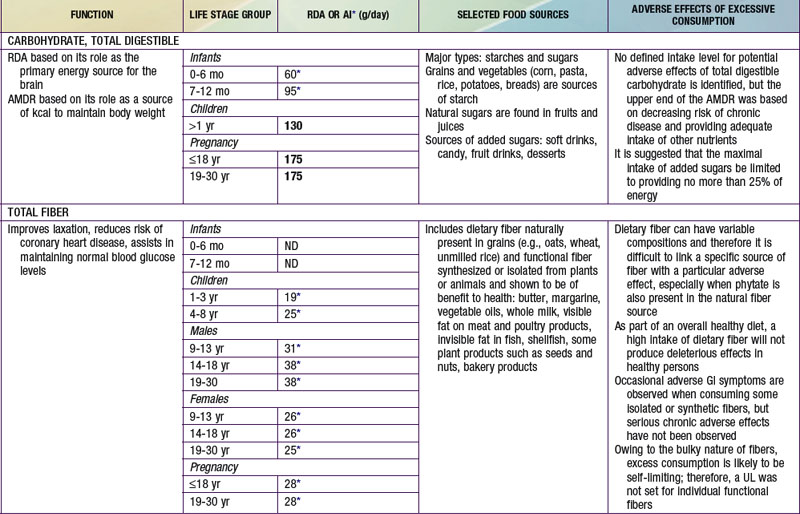

AMDR for carbohydrates is in Table 41-4. The minimum intake is based on estimated brain requirements. Chronic low carbohydrate intake results in ketosis, for which the long-term effects on growth and development have not been established. Although a UL for carbohydrates has not been set, a maximal intake of <25% or <10% of total energy intake from added sugars has been proposed in various dietary guidelines. Higher intakes of added sugar can displace other macro- and micronutrients and increase risk for nutrient deficiency and excessive energy intake. There is no distinct advantage or benefit obtained from discretionary calorie intake such as that provided by the consumption of added sugars. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans endorses diets with carbohydrates from a variety of fiber-rich fruits, vegetables, and whole grains in addition to the recommendations for reduced added sugar (sucrose) intake.

Fiber

Data are insufficient to establish an EAR; an AI for dietary fiber has been established based on the intake levels associated with reducing risk for cardiovascular disease and in lowering or normalizing serum cholesterol (see Table 41-5). A UL has not been established for fibers, which are not thought to be harmful to human health.

Micronutrients

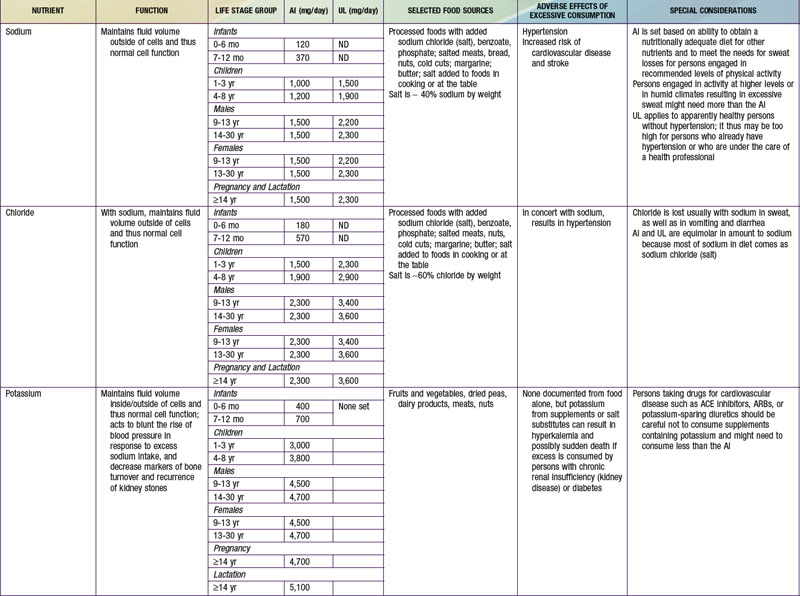

Potassium and sodium are the main intra- and extracellular cations, respectively, and involved in transport of fluids and nutrients across the cellular membrane. There is an AI set for potassium related to its effects in maintaining lower blood pressure, to reduce risk for nephrolithiasis, and to support bone health. Moderate potassium deficiency can occur even in the absence of hypokalemia and can result in increased blood pressure, stroke, and other cardiovascular disease. Most American children have potassium intake below the current recommendations. African-Americans in particular are at increased risk for potassium deficiency. For persons at increased risk for hypertension and who are salt sensitive, reducing sodium intake and increasing potassium intake is advised. Leafy green vegetables, vine fruit (such as tomatoes) and root vegetables are good food sources of potassium (see Table 41-7). Conversely, persons with impaired renal function might need to reduce their potassium intake; hyperkalemia can increase risk for fatal cardiac arrhythmias among these patients.

Water

The water requirement and content as a proportion of body weight are highest in infants and decrease with age. Water intake is achieved with liquid and food intake, and losses include excretion in the urine and stool as well as insensible evaporative and vapor losses through the skin, respiratory tracts, and mucosal membranes. An AI has been established for water (see Table 41-7). Special considerations are required by life stages and by basal metabolic rate, physical activity, body proportions (surface area to volume), environment, and underlying medical conditions. Breast milk and infant formula provide adequate water, and additional water intake is not required until complementary foods are introduced. Although water contains no calories, the concern is that water intake might actually decrease breast milk intake and displace the intake of essential nutrients during this metabolically very active life stage. The high ratio of body surface area to volume in infancy, as well as the high respiratory rate, increases insensible water losses, which in part explain the increased fluid needs in infants and young children.

Bhargava A, Amialchuk A. Added sugars displaced the use of vital nutrients in the National Food Stamp Program Survey. J Nutr. 2007;137:453-460.

Bhutta ZA. Childhood iron and zinc deficiency in resource poor conuntries. BMJ. 2007;334:104-105.

Bibbins-Dormingo K, Chertow GM, Coxson PG, et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:590-598.

Devaney B, Ziegler P, Pac S, et al. Nutrient intakes of infants and toddlers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:s14-s21.

Fischer Walker CL, Ezzati M, Black RE. Global and regional child mortality and burden of disease attributable to zinc deficiency. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:591-597.

Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LL, et al. American Heart Association: Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: a guide for practitioners. Pediatrics. 2006;117:544-559.

Havas S, Roccella EJ, Lenfant C. Reducing the public health burden from elevated blood pressure levels in the United States by lowering intake of dietary sodium. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:19-22.

Holick MF, Chen TC. Vitamin D deficiency: a worldwide problem with health consequences. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1080S-1086S.

Kleinman RE, editor. Pediatric nutrition handbook, ed 6, Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009.

Lazzerini M. Effect of zinc supplementation on child morality. Lancet. 2007;370:1194-1195.

Ludwig DS. The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2002;287:2414-2423.

Maqbool A. Colon: structure and function. In: Caballero B, Allen L, Prentice A, editors. Encyclopedia of human nutrition. ed 2. London: Elsevier; 2006:449-460.

Maqbool A, Shingara IO, Stallings VA. Clinical assessment of nutritional status. In: Walker WA, Watkins JB, Duggan C, editors. Nutrition in pediatrics. ed 4. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker; 2008:5-13.

National Center for Health Statistics. CDC growth charts (website). www.cdc.gov/GrowthCharts/. Accessed May 23, 2010

Institute of Medicine. Otten JJ, Hellwig JP, Meyers LD, editors. Dietary reference intakes: the essential guide to nutrient requirements. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2006.

Reeds PJ. Dispensable and indispensable amino acids for humans. J Nutr. 2000;130:1835S-1840S.

Rovner AJ, O’Brien KO. Hypovitaminosis D among healthy children in the United States: a review of the current evidence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:513-519.

Saintonge S, Bang H, Gerber LM. Implications of a new definition of vitamin D deficiency in a multiracial US adolescent population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Pediatrics. 2009;123:797-803.

Schroeder DG, Martorell R, Rivera JA. Age differences in the impact of nutritional supplementation on growth. J Nutr. 1995;125(4 Suppl):1051S-1059S.

Simopoulos AP. Essential fatty acids in health and chronic disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(3 Suppl):560S-569S.

Committee on Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Stallings VA, Yaktine AL, editors. Nutrition standards for foods in schools. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2007.

Stoltzfus RJ. Iron deficiency: global prevalence and consequences. Food Nutr Bull. 2003;24(4 Suppl):S99-S103.

United Nations Children’s Fund. The state of the world’s children 2008 (website). www.unicef.org/sowc08/. Accessed July, 2010

United States Department of Agriculture. Dietary guidelines for Americans (website). www.healthierus.gov/dietaryguidelines. Accessed May 23, 2010

United States Department of Agriculture. MyPyramid (website). www.mypyramid.gov/. Accessed May 23, 2010

United States Food and Drug Administration. Claims that can be made for conventional foods and dietary supplements (website). www.fda.gov/Food/LabelingNutrition/LabelClaims/ucm111447.htm. Accessed July 1, 2010

Vos MB, Kimmons JE, Gillespie C, et al. Dietary fructose consumption among US children and adults: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Medscape J Med. 2008;10:160.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO child growth standards (website). www.who.int/childgrowth/en/. Accessed May 23, 2010

World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. WHO Technical Report Series # 916. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.