Noncardiac Implantable Devices

In addition to cardiac pacemakers and defibrillators, a number of noncardiac devices have been developed for electronic neuromodulation and drug delivery.1,2 Although these devices are placed by a variety of subspecialists for the treatment of chronic illnesses, if the devices malfunction, patients may arrive at the emergency department in an acute state, thereby necessitating intervention by the emergency physician.

Insulin Infusion Devices

External insulin infusion devices are becoming increasingly popular since their introduction in 1974. As of 2007, more than 375,000 external insulin infusion pumps are in use.3

Anatomy

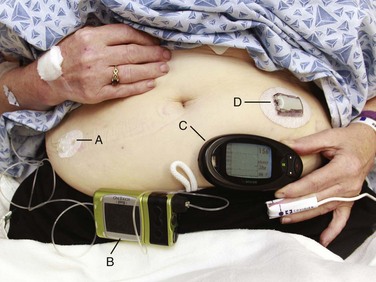

An external insulin infusion pump device consists of a portable, programmable infusion pump connected to a subcutaneously implanted catheter maintained in place with adhesive tape (Fig. 71-1). The implanted catheter site varies, but it is commonly placed on the abdomen in adults and on the buttocks in young children. The thighs, hips, and upper part of the arms are other sites. It is recommended that the implanted catheter be replaced every 2 to 3 days.

Device Complications

In 2010, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published a panel report that highlighted problems associated with insulin infusion devices.3 From the top five device manufacturers, the FDA noted 16,640 adverse events, including 310 deaths, 12,093 injuries, and 4,294 malfunctions. Box 71-1 lists the most frequently reported problems with devices in descending frequency. Box 71-2 lists the most frequently reported patient-oriented adverse reactions, which include hyperglycemia and hospitalization.

Intrathecal Drug Delivery Systems

Intrathecal drug delivery systems (IDDSs) have been in clinical use since the 1980s. Although data are accumulating, very few robust clinical studies of IDDSs have been published.4 The FDA approved the use of intrathecal baclofen in 1992 for severe spasticity secondary to spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, or stroke. In addition, the FDA approved the use of intrathecal morphine in 1995 for chronic pain refractory to traditional medical therapies. An IDDS is also used for the delivery of chemotherapeutic medications for specific oncologic conditions. Moreover, there are numerous off-label uses of various intrathecal medications.

Anatomy

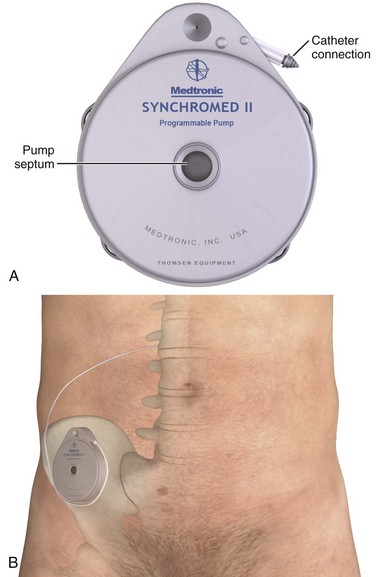

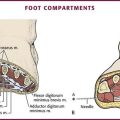

Currently, Medtronic is the only IDDS manufacturer in the United States. Medtronic’s SynchroMed II Programmable Infusion Pump consists of an infusion pump connected to an intrathecal catheter (Fig. 71-2A). The infusion pump is available with a refillable reservoir of either 20 or 40 mL. The pump is powered by a permanent lithium battery that cannot be recharged. The battery must be surgically replaced every 4 to 7 years. Normal refill intervals are usually between 2 and 3 months.

The pump is placed in a subcutaneous pocket, generally in the right lower abdominal region. The intrathecal catheter is inserted slightly lateral to the spinous process into an appropriate lower lumbar interspace and connects to the pump via a subcutaneous tract that wraps around the abdominal wall (see Fig. 71-2B).

Device Complications

Several studies have shown a significant rate of adverse effects in IDDS patients ranging anywhere from 2% to 50%.5,6

Medications currently in use via IDDSs include clonidine, bupivacaine, morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl, ziconotide, and baclofen.7 Of these, bupivacaine and morphine have specific antidotes (Intralipid and naloxone, respectively). Medication overdoses, aside from standard emergency management, can also be treated by accessing the infusion pump reservoir.

A unique complication related to IDDSs that was identified by the FDA and issued as a warning is the formation of a granuloma at the tip of the intrathecal catheter. This can obstruct infusion of the medication and lead to withdrawal symptoms.8,9

With regard to intrathecal opioids, the degree of lipophilicity of the intrathecal opioid affects its pharmacokinetics. Fentanyl, with its high lipophilicity, is absorbed rapidly by the spinal cord and little is left to ascend in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Thus, it has a rapid onset and shorter duration with fewer adverse effects. Morphine, with its high hydrophilicity, penetrates the spinal cord slowly, which allows a considerable amount of the drug to ascend in CSF. This, in turn, results in a slower onset and longer duration with a higher incidence of adverse effects, including pruritus, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, changes in mental status, and respiratory depression.10,11

Procedure

When there is concern for medication overdose secondary to malfunction of the device, in addition to emergency medical management, the emergency physician can empty the pump reservoir by using the steps outlined in Box 71-3.

Access the Medtronic online manual and review the steps necessary to remove the contents of the pump reservoir and thus prevent further infusion of intrathecal medication (Fig. 71-3).12 Assuming no contraindications, withdraw an additional 30 to 40 mL of CSF by lumbar puncture to reduce the drug’s concentration in CSF.

VNS

Since the 1930s, numerous studies have shown the effects of vagal nerve stimulation on cerebral activity. In 1985, Zabara demonstrated the anticonvulsant effect of vagal nerve stimulation through animal studies.13 In 1997 the FDA approved use of the vagal nerve stimulator (VNS) as an adjunctive treatment of medically refractory partial-onset epilepsy.14 Subsequently, in 2005 the FDA approved use of the VNS as an adjunctive therapy for treatment-resistant depression.15,16

Anatomy

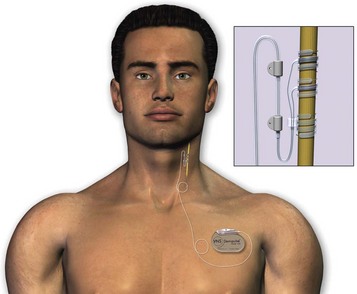

The device is composed of a generator attached to a bipolar VNS lead. The generator is approximately 4 cm long, 6 cm wide, and 7 mm thick and weighs 25 g. Figure 71-4 shows how the generator is implanted into subcutaneous tissue in the left upper part of the chest, with the electrode lead being attached to the left cervical vagus nerve trunk. Interrogation and programming of the device are conducted with a magnetic field–induced, external programming wand connected to a handheld computer. The variable settings that can be adjusted include current output, signal frequency, pulse width, and on/off stimulation times. When reset, the generator is on for 30 seconds, followed by 60 minutes off.17,18

Device Complications

In addition to surgery-related risks and complications, if the patient complains of severe neck pain, worsening hoarseness, choking, or difficulty breathing, always consider device-specific complications. Voice alteration or hoarseness is the most common device-specific adverse effect, with more than 50% of patients being affected. Other common side effects include increased coughing, shortness of breath, and pharyngitis. Less common device-specific adverse effects reported during clinical studies include ataxia, dyspepsia, dysphagia, hypoesthesia, infection, insomnia, laryngismus, nausea, pain, paresthesia, and vomiting.17,18

Procedure

In cases of emergency, diagnostic uncertainty, or significant adverse effects, turn off the pulse generator temporarily by holding a magnet over the generator (Box 71-4). Pass the external VNS magnet over the generator to independently trigger it. This on-demand stimulation, if initiated at the onset of an aura or seizure, may abort the attack or, if initiated during a seizure, may halt its progression. Holding a magnet over the pulse generator causes a reed switch inside the generator to close. When the magnet closes the reed switch, the signal cannot be conducted and the pulse generator is temporarily turned off. When the magnet is removed, the switch opens and the generator is turned back on.17,18

Unlike the typical donut-shaped magnet of a cardiac pacemaker, the VNS magnet is bar shaped, as shown in Figure 71-5. Be aware that patients with VNSs are typically provided with two magnets: one fitted with a wristband and the other fitted with a belt clip.

Figure 71-5 Vagal nerve stimulator magnet.

Additional Implantable Devices

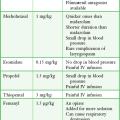

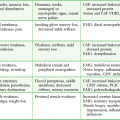

There are several additional noncardiac implantable devices that the emergency physician may encounter, which are outlined in Table 71-1. However, should these devices malfunction, there are no specific procedures to be aware of in the emergency setting beyond supportive treatment.

TABLE 71-1

Additional Noncardiac Implantable Devices

| DEVICE | DESCRIPTION | MALFUNCTION |

| Bladder stimulator or sacral nerve stimulator | Stimulator wire inserted into the S3 sacral foramen adjacent to the sacral nerve for the treatment of urinary incontinence in the setting of severe neurologic disease20 | Hardware complications include infection, skin irritation, and wire migration20 |

| Deep brain stimulator | Stimulator implanted into the thalamus for treatment of Parkinson’s disease, tremor, and dystonia1 | Hardware complications include infection and lead migration21 |

| Gastric pacemaker | Neurostimulator with implanted leads into the gastric musculature to improve gastroparesis22 | Gastric wall perforation, infection, and lead migration22 |

| Phrenic nerve stimulator or diaphragmatic pacemaker | Electrodes implanted into each phrenic nerve with a receiver implanted into subcutaneous tissue. An external transmitter controls the receiver. Used to treat respiratory insufficiency secondary to upper motor neuron paralysis or respiratory drive dysfunction23,24 | Pneumothoraces have been described immediately after implantation. Infection and wire migration have been described.23,24 Failure of the pacemaker is treated by ventilatory support |

MRI and Implantable Devices

For patients with electrically, magnetically, or mechanically activated implants, the FDA requires labeling that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is contraindicated,25 and indeed, manufacturers of gastric, urinary, diaphragmatic, and spinal cord stimulators list these devices as absolute contraindications to MRI.21 However, there are a number of clinical series and case reports indicating the compatibility of certain devices with MRI. For VNSs, a 1.5-T magnet has been studied and deemed compatible with MRI by the manufacturer.21,26,27 However, this compatibility is limited to MRI machines with transmit and receive head coils. MRI machines with transmit body coils and receive-only head coils may cause heat injury and damage the device. For deep brain stimulation, some studies have suggested that MRI is safe in certain circumstances,28 but case reports of patient injury can be found in the literature.29 For IDDSs, pumps have been shown to stop operating while in the magnetic field but resume functioning once removed.25 Insulin pumps may easily be removed in the event that MRI is required.

References

1. Venkatraghavan, L, Chinnapa, V, Peng, P, et al. Non-cardiac implantable electrical devices: brief review and implications for anesthesiologists. Can J Anaesth. 2009;56:320–326.

2. Krames, ES. Neuromodulation devices are part of our “tools of the trade.”. Pain Med. 2006;7(suppl 1):S3–S5.

3. Federal Drug Administration. Federal Drug Administration Panel on General Hospital and Personal Use Medical Device Panel on Insulin Infusion Pumps. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/advisorycommittees/committeesmeetingmaterials/medicaldevices/medicaldevicesadvisorycommittee/generalhospitalandpersonalusedevicespanel/ucm202779.pdf, 2010. [Retrieved from Accessed 9/18/11].

4. Deer, T, Krames, ES, Hassenbusch, SJ, et al. Polyanalgesic Consensus Conference 2007: recommendations for the management of pain by intrathecal (intraspinal) drug delivery: report of an interdisciplinary expert panel. Neuromodulation. 2007;10:300–328.

5. Zuckerbraun, NS, Ferson, SS, Albright, AL, et al. Intrathecal baclofen withdrawal: emergent recognition and management. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:759–764.

6. Stempien, L, Tsai, T. Intrathecal baclofen pump use for spasticity: a clinical survey. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;79:536–541.

7. Johnson, ML, Visser, EJ, Goucke, CR. Massive clonidine overdose during refill of an implanted drug delivery device for intrathecal analgesia: a review of inadvertent soft-tissue injection during implantable drug delivery device refills and its management. Pain Med. 2011;12:1032–1040.

8. Follett, KA, Naumann, CP. A prospective study of catheter-related complications of intrathecal drug delivery systems. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19:209–215.

9. Kamaran, S, Wright, BD. Complications of intrathecal drug delivery systems. Neuromodulation. 2001;4:111–115.

10. Ruan, S. Drug-related side effects of long-term intrathecal morphine therapy: a focused review. Pain Physician. 2007;10:357–366.

11. Ruan, X, Couch, JP, Shah, R, et al. Respiratory failure following delayed intrathecal morphine pump refill, a valuable, but costly lesson. Pain Physician. 2010;13:337–341.

12. Medtronic. Indications, drug stability, and emergency procedures; SynchroMed and IsoMed implantable infusion systems reference manual. http://professional.medtronic.com/wcm/groups/mdtcom_sg/@mdt/@neuro/documents/documents/pump-indc-refmanl.pdf, 2009. [Retrieved from Accessed 9/18/11].

13. Zabara, J. Peripheral control of hypersynchronous discharge in epilepsy. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1985;61:162.

14. DeGiorgio, CM, Schachter, SC, Handforth, A, et al. Prospective long-term study of vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of refractory seizures. Epilepsia. 2000;41:1195–1200.

15. Rush, AJ, Marangell, LB, Sackeim, HA, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a randomized, controlled acute phase trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:347–354.

16. Daban, CC, Martinez-Aran, A, Cruz, N, et al. Safety and efficacy of vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression. A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2008;110:1–15.

17. Cyberonics. Physician’s Manual, VNS Therapy Pulse Model 102 Generator and VNS Therapy Pulse Duo Model 102R Generator. Part I—Introduction—Indications, Warnings, and Precautions. http:// dynamic.cyberonics.com/manuals, 2011. [Retrieved from Accessed 2/15/13].

18. Cyberonics. Epilepsy Physician’s Manual, NeuroCybernetic Prosthesis System NCP Pulse Generator Models 100 and 101. http:// dynamic.cyberonics.com/manuals, 2002. [Retrieved from Accessed 2/15/13].

19. Hatton, K, McLarney, J, Pitmann, T, et al. Vagal nerve stimulation: overview and implications for anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:1241–1249.

20. Jezernik, S, Craggs, M, Grill, WM, et al. Electrical stimulation of the treatment of bladder dysfunction: current status and future possibilities. Neurol Res. 2002;24:413–430.

21. Levin, G, Ortiz, AO, Katz, DS. Noncardiac implantable pacemakers and stimulators: current role and radiographic appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:984–991.

22. Lin, Z, Forster, J, Sarosiek, I, et al. Treatment of gastroparesis with electrical stimulation. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:837–848.

23. Chervin, RD, Guilleminault, C. Diaphragm pacing for respiratory insufficiency. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1997;14:369–377.

24. Weese-Mayer, DE, Morrow, AS, Brouillette, RT, et al. Diaphragm pacing in infants and children: a life-table analysis of implanted components. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:974–979.

25. Schueler, BA, Parrish, TB, Lin, JC, et al. MRI compatibility and visibility assessment of implantable medical devices. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9:596–603.

26. Sucholeiki, R, Alsaadi, TM, Morris, GL, et al. fMRI in patients implanted with a vagal nerve stimulator. Seizure. 2002;11:157–162.

27. Cyberonics. Physician’s Manual, VNS Therapy Pulse Model 102 Generator and VNS Therapy Pulse Duo Model 102R Generator. MRI with the VNS Therapy System. http://dynamic.cyberonics.com/manuals, 2011. [Retrieved from Accessed 2/15/13].

28. Tronnier, VM, Staubert, A, Hähnel, S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging with implanted neurostimulators: an in vitro and in vivo study. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:118–125.

29. Rezai, AR, Phillips, M, Baker, KB, et al. Neurostimulation system used for deep brain stimulation (DBS): MR safety issues and implications of failing to follow safety recommendations. Invest Radiol. 2004;39:300–303.