6 New Days for Old Ways in Treating Giant Aneurysms—From Hunterian Ligation to Hunterian Closure?

Hunterian ligation

Hunterian ligation (i.e., proximal artery ligation) was the first surgical method for treating intracranial aneurysms. At the end of 18th century, a Scottish surgeon and scientist, John Hunter, established the procedure more or less in its current fashion by ligating certain peripheral arteries.2,8,12 However, the first planned ICA ligation for the treatment of a preoperatively diagnosed nontraumatic saccular aneurysm was apparently performed in 1928,16 and in subsequent decades several papers reported inconsistent mortality rates of the procedure. In 1966, a highly detailed and one-of-a-kind analysis of nearly 800 cases of Hunterian ligation for aneurysm patients reported an ischemic complication rate of 30% and a mortality rate of 24%.11 However, 89% of the occlusions were CCA occlusions, and they were mainly performed in the acute phase of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Following Hunterian ligation, only 16 (12%) and three (2%) out of 129 patients with unruptured aneurysms experienced ischemic deficits or died, respectively. Hunterian ligation of the ICA had almost a double risk of ischemic complications in comparison to CCA occlusion, even though severely ill and high-risk patients were more frequently selected for CCA rather than ICA occlusion.

The series of Drake and Peerless, which the senior author (JH) has scrutinized, represents the largest and most experienced data of the procedure for giant aneurysms to date; it consists of 732 giant aneurysms, 396 of which were treated with Hunterian ligation before December 1992. Due to their special referral policy, posterior circulation aneurysms outnumbered anterior circulation aneurysms in the series.21 Excluding infraclinoid aneurysms (five petrous and 77 intracavernous carotid aneurysms), more than two thirds (69%) of the 253 giant anterior circulation aneurysms were treated with direct clipping, whereas only one third (32%) of the 397 giant posterior circulation aneurysms were directly clipped. For the remainder, Hunterian ligation was used in the treatment of 48% and 60% of the anterior and posterior circulation aneurysms, respectively.

Today, even though most saccular aneurysms at any site can technically be considered as clippable, especially fusiform, dissecting highly atherosclerotic and giant aneurysms remains cumbersome. Since giant aneurysms often have a very slow or stagnant intra-aneurysmal blood flow, resulting in asymptomatic or symptomatic distal perfusion changes, Hunterian ligation can provide better than expected surgical results in these otherwise inoperable and unfavorable cases. For the aforementioned reasons, Hunterian ligation has remained a useful adjunct to tackle giant aneurysms, often combined with a bypass procedure. Therefore, the number of Hunterian ligation procedures performed at our institution has continued to be more or less the same throughout the years. Disappointing results in using Hunterian ligation for patients with ruptured giant aneurysms have made us cautious in attempting Hunterian ligation in the week following SAH.11,13

Anterior circulation

Giant ICA Aneurysms

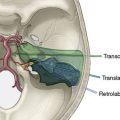

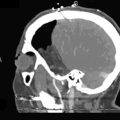

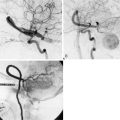

Permanent occlusion of the ICA with or without a prior test occlusion leads to a high cumulative stroke rate and mortality of 26% and 12%, respectively.9 Therefore, a preoperative evaluation of collateral potential of the circle of Willis is necessary. After a diagnostic angiography, we typically perform a test occlusion for a minimum of 30 minutes using an inflated endovascular balloon in the high cervical ICA (at the C1-2 level of the ICA) of a conscious patient. If the patient tolerates the test occlusion without neurological symptoms, and the angiographic architecture of the venous phase does not show substantial asymmetry, Hunterian closure of the ICA can be considered as a treatment option. The venous phase is symmetrical if the venous phase of both cerebral hemispheres is synchronous (venous filling delay is less than 0.5 seconds) after collateral filling via the anterior communicating artery, or if the venous phase of the posterior circulation on vertebral angiography is simultaneous (venous filling delay is less than 0.5 seconds) after collateral filling via the posterior communicating artery.18 We do not routinely use blood flow or perfusion analyses (e.g., MRI-NOVA, perfusion CT, perfusion MRI) during or after the balloon test occlusion. At present, we do not perform Hunterian closure of the CCA, because we have seen retrograde recanalization of the ICA, which increases the risk of aneurysm rupture.11 In addition, we have not found test occlusions of the CCA reliable, and permanent occlusion of the CCA evidently affects EC-IC collateral flow. Whatever the clinical preoperative evaluation of the collateral flow potential of the ICA territory, unexpected ischemic events are always possible after Hunterian closure of the ICA. Even though today it is also possible to measure the blood flow intraoperatively, current flow probes and intraoperative monitoring modalities cannot be used to reliably estimate the circulatory changes after Hunterian closure.

If any doubts or objective signs of insufficient collateral flow of the ICA territory exist, it is advisable to do a bypass instead of sole Hunterian closure or a direct attack to the aneurysm. Depending on the degree of the patient’s collateral circulation, either a low-flow or a high-flow replacement or protective bypass is constructed, prior to occlusion of the ICA or direct aneurysm clipping. When a high-flow bypass is needed, we usually construct a nonocclusive, high-flow, laser-assisted Excimer Laser-Assisted Nonocclusive Anastomosis (ELANA) bypass.17 Hunterian closure, trapping, or direct clipping of the giant aneurysm is performed either immediately after the bypass procedure in the same session or later. Giant ICA aneurysms located in the supraclinoid segment of the ICA are usually the most difficult to treat. The most difficult ones are located at the bifurcation, where direct clipping may easily occlude anterolateral central arteries in addition to A1 or M1 origins. Unfortunately, bypass requirements for giant ICA bifurcation aneurysms are also very demanding, since sometimes even a Y-shaped or dual bypass to both A1 and to distal M1 segments is needed in order to treat the lesion. Flow reduction with Hunterian closure without bypass may in rare cases be the only reasonable treatment option, but whether this procedure provides any benefit for patients is unknown.

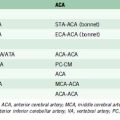

Giant ACA and MCA Aneurysms

The incidence of giant anterior cerebral artery (ACA) aneurysms, especially of ruptured ones, is very low. Before the microsurgery era, Hunterian closure of the dominant/only A1 was a frequently used surgical alternative even when small-size anterior communicating artery aneurysms were to be treated. Sudden occlusion of the dominant A1 causes ischemic complications almost without exception. A giant A1 aneurysm can be rather safely clipped or sometimes even trapped if the contralateral A1 is filling both A2s. According to Drake, leptomeningeal collaterals from the middle cerebral artery (MCA) and posterior cerebral artery (PCA) may fill A2 segments sufficiently, even in a retrograde fashion when both A1s are occluded. Drake used Hunterian closure of the A1 segment in some cases to treat giant aneurysms of the ACA,7 and also a so-called tourniquet occlusion of the A1 segments in conscious patients when direct clipping was not possible. Giant ACA aneurysms are very difficult to treat with direct clipping, but after temporary clipping of both A1s and one or two A2s, it is often possible to dissect the aneurysm sac, evacuate the thrombus, and finally, clip the aneurysm. The problem is how to keep the medial lenticulostriate arteries patent even if blood supply to the A2s is provided by the contralateral A1.

Giant MCA aneurysms are the most common giant aneurysms in Finland, and they represent about 4% of all MCA aneurysms.3 Most of these aneurysms are MCA bifurcation aneurysms, and approximately half of all giant MCA aneurysms can be surgically resected. After the resection, the diseased MCA segment is reconstructed by clipping the aneurysm base—for example, in tandem fashion—and sometimes suturing of the resected aneurysm wall is necessary. A vascular clamp may sometimes be helpful in assisting direct clipping of thick-walled and calcified giant aneurysms.10 For patients whose aneurysms cannot be directly resected and clipped, one option is to revascularize the distal-to-aneurysm branches with a bypass and then induce a flow change and thrombosis of the aneurysm by Hunterian closure.

Posterior circulation

Giant Vertebrobasilar Junction, Basilar Trunk, and Basilar Tip Aneurysms

Vertebrobasilar junction aneurysms, which very often associate with proximal basilar fenestration,14 as well as saccular basilar trunk aneurysms, are extremely rare (<0.1% of all saccular aneurysms). Most of the large and giant vertebrobasilar junction and basilar trunk aneurysms are fusiform or dissecting in nature. We have been successful in treating these aneurysms with direct surgery, which, in practice, is a technically demanding high-risk treatment option. In the presence of a good posterior communicating artery/arteries (>1 mm), unilateral or bilateral Hunterian closure of the VA or direct Hunterian closure of the basilar artery (BA) may be applied to induce thrombosis of the aneurysm due to flow diversion. Therefore if the patient tolerates a unilateral VA test occlusion time of 30 minutes and has symmetrical venous phases, one VA can be sacrificed relatively safely. After 2 to 4 weeks, when natural adaptation of the collateral vasculature has already occurred to some extent, another test occlusion and hopefully permanent occlusion of the remaining patent VA can be performed. Our experience indicates that this “tandem occlusion” strategy may facilitate occlusion of both VAs in cases where this seemed too risky in the first place. If collateral flow through posterior communicating arteries is insufficient, a bypass has to be constructed, such as to the P1 segment prior to occlusion of the BA or VAs. Since most of the giant BA tip aneurysms can less often be safely clipped, and endovascular surgery offers unsatisfactory results, Hunterian closure of the BA in the treatment of giant basilar tip saccular aneurysms is a good option when functioning posterior communication arteries are present. Unfortunately, sometimes the giant aneurysm remains open and growing even after Hunterian closure due to this vivid collateral flow through posterior communicating arteries. In brief, giant BA tip aneurysms are very difficult to treat both surgically and endovascularly, and poor outcome is often observed using either modality.

Giant PCA Aneurysms

In the Drake’s series of 31 PCA aneurysms, 13 were giant aneurysms.5,6 In the series of 174 giant intracranial aneurysms, 13 (7.5%) were giant PCA aneurysms, of which nine P1 and P2 aneurysms were treated with Hunterian closure or trapping.5 According to Drake, only one patient (trapped P2 segment giant aneurysm) developed a visual field defect, and it was speculated that good collateral circulation was the main reason for the lack of serious neurological sequelae.5 Yasargil has also reported good results after trapping five nonclippable fusiform and giant aneurysms in the P1 and P2 segments.20 There are several reports on giant PCA aneurysms treated with Hunterian closure or trapping, without any serious neurological deficits. The decision between trapping and Hunterian closure is ultimately based on the intraoperative evaluation of the presence of perforators originating from the diseased segment. If there is any danger of causing iatrogenic thalamic syndrome (occlusion of the thalamogeniculate artery), it is advisable to do Hunterian closure alone instead of trapping.

Discussion

Based on the International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms (ISUIA) data, the lifetime rupture risk of giant aneurysms has been estimated to exceed 87% in a 30-year-old patient and 71% in a 50-year-old patient.1 Thus, it is evident that most of the giant intradural ICA aneurysms should be treated. Except for the ICA bifurcation aneurysms, giant ICA aneurysms are very satisfactorily and safely treated with Hunterian closure of the ICA, if the patient tolerates the occlusion. Only a minority of giant ICA aneurysms remain unchanged in size after ICA occlusion,4 and symptoms of mass effect are cured or improved in more than 90% of patients.4 Since Hunterian closure of the ICA is a simple, safe, and effective therapy for these patients,4 it is fair to say that there are still some scientific grounds for Hunterian closure in the treatment of giant ICA aneurysms. However, because ICA occlusion may cause progressive degenerative processes in the brain due to changes in cerebral oxygen metabolism,19 we try to avoid ICA occlusion in patients aged <50 years. Furthermore, ICA occlusion is far from optimal for intracranial aneurysms due to its ischemic and embolic complication risks. In recent years, new endovascular techniques capable of sparing vessel patency have become available. Indeed, these new microcatheter-delivered, self-expanding, and stent-like endovascular constructs (i.e., flow-diverting stents) are engineered specifically for the treatment of intracranial aneurysms, and they completely exclude the aneurysm from circulation. These devices represent a revolutionary remodeling tool for aneurysm treatment, especially for the treatment of symptomatic cavernous sinus aneurysms. However, these devices are not yet established widely enough, and objective reports of complication rates and long-term results have yet to be published.

In contrast to the P1, A1, and M1 segments, microsurgery in the treatment of giant P2, basilar trunk, vertebrobasilar junction, and VA aneurysms has become a secondary option in a number of institutions. This also applies to surgical Hunterian closure. Despite the giant steps of the ongoing endovascular revolution, “aneurysm surgeons should maintain technical proficiency with difficult lesions.”15 Indeed, we believe that in very experienced hands, the procedural risk of surgery of giant aneurysms in any location is acceptable and comparable to that of endovascular treatments. Unorthodox ideas, innovative applications, and imagination are required to revolutionize neurovascular surgery again, such as in the 1960s.

1 Chang H.S. Simulation of the natural history of cerebral aneurysms based on data from the International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:188-194.

2 Cooper B.B. Lectures on the Principles and Practice of Surgery. Philadelphia: Blanchard and Lee, 1852.

3 Dashti R., Hernesniemi J., Niemela M., et al. Microneurosurgical management of middle cerebral artery bifurcation aneurysms. Surg Neurol. 2007;67:441-456.

4 de Gast A.N., Sprengers M.E., van Rooij W.J., et al. Midterm clinical and magnetic resonance imaging follow-up of large and giant carotid artery aneurysms after therapeutic carotid artery occlusion. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:1025-1029. discussion 1029–1031

5 Drake C.G. Giant intracranial aneurysms: experience with surgical treatment in 174 patients. Clin Neurosurg. 1979;26:12-95.

6 Drake C.G. The treatment of aneurysms of the posterior circulation. Clin Neurosurg. 1979;26:96-144.

7 Drake C.G., Peerless S.J., Ferguson G.G. Hunterian proximal arterial occlusion for giant aneurysms of the carotid circulation. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:656-665.

8 Hunter J. Some Observations on Digestion. London: Longman et al, 1935.

9 Linskey M.E., Jungreis C.A., Yonas H., et al. Stroke risk after abrupt internal carotid artery sacrifice: accuracy of preoperative assessment with balloon test occlusion and stable xenon-enhanced CT. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:829-843.

10 Navratil O., Lehecka M., Lehto H., et al. Vascular clamp-assisted clipping of thick-walled giant aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:113-120. discussion 120–121

11 Nishioka H. Results of the treatment of intracranial aneurysms by occlusion of the carotid artery in the neck. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:660-704.

12 Paget S. John Hunter, Man of Science and Surgeon. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1897.

13 Peerless S.J., Hernesniemi J.A., Gutman F.B., et al. Early surgery for ruptured vertebrobasilar aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:643-649.

14 Peluso J.P., van Rooij W.J., Sluzewski M., et al. Aneurysms of the vertebrobasilar junction: incidence, clinical presentation, and outcome of endovascular treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1747-1751.

15 Sanai N., Tarapore P., Lee A.C., et al. The current role of microsurgery for posterior circulation aneurysms: a selective approach in the endovascular era. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:1236-1249. discussion 1249–1253

16 Schorstein J. Carotid ligation in saccular intracranial aneurysms. Br J Surg. 1940;28:50-70.

17 Tulleken C.A., Verdaasdonk R.M., Beck R.J., et al. The modified excimer laser-assisted high-flow bypass operation. Surg Neurol. 1996;46:424-429.

18 van Rooij W.J., Sluzewski M., Metz N.H., et al. Carotid balloon occlusion for large and giant aneurysms: evaluation of a new test occlusion protocol. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:116-121. discussion 122

19 Yamauchi H., Pagani M., Fukuyama H., et al. Progression of atrophy of the corpus callosum with deterioration of cerebral cortical oxygen metabolism after carotid artery occlusion: a follow-up study with MRI and PET. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;59:420-426.

20 Yasargil M.G. Microneurosurgery. George Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, 1984.

21 Drake C.G., Peerless S.J., Hernesniemi J. Surgery of vertebrobasilar aneurysms. Springer-Verlag: Wien; 1996.