Chapter 536 Neuropathic Bladder

Neuropathic bladder dysfunction in children usually is congenital, generally resulting from neural tube defects or other spinal abnormalities. Acquired diseases and traumatic lesions of the spinal cord are less common. Central nervous system tumors, sacrococcygeal teratoma, spinal abnormalities associated with imperforate anus (Chapter 336), and spinal cord trauma also can result in abnormal innervation of the bladder and/or sphincter.

Neural Tube Defects

Neural tube defects, resulting from failure of the neural tube to close spontaneously between the 3rd and 4th wk in utero, result in abnormalities of the vertebral column that affect spinal cord function, including myelomeningocele and meningocele (Chapter 585). A few medical centers in the USA have been performing antenatal myelomeningocele closure, but follow-up studies of the urinary tract have not shown a definite improvement in lower urinary tract function.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

The most important urologic consequences of neuropathic bladder dysfunction associated with neural tube defects are urinary incontinence (Chapter 537), urinary tract infections (UTIs; Chapter 532), and hydronephrosis from vesicoureteral reflux or detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia. Pyelonephritis (Chapter 532) and renal functional deterioration (see Chapter 529) are common causes of premature death of affected patients.

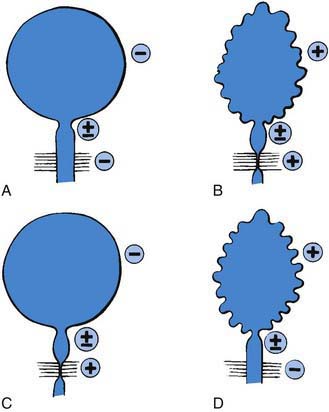

In the neonate, renal ultrasonography, assessment of postvoid residual urine volumes, and a voiding cystourethrogram are performed after closure of the myelomeningocele. About 10-15% of patients have hydronephrosis, and renal malformations are common; 25% have vesicoureteral reflux. A urodynamic study also should be performed. This study involves filling the bladder with saline, measuring the bladder volume and pressure, and assessing sphincter tone. During bladder filling, the bladder might show uninhibited (premature) contractions at low volumes, normal bladder volume with contraction at an appropriate volume, or atonia (lack of bladder contraction). Bladder compliance or elasticity also may be reduced. The sphincter can show normal tone with relaxation during bladder contraction, reduced or absent tone, or normal or increased tone that increases during bladder contraction (termed detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia) (Fig. 536-1).

Renal Damage

Renal damage usually results from failure of the sphincter to relax during a spontaneous bladder contraction. This dyssynergia results in functional obstruction of the bladder outlet, leading to high intravesical pressure, bladder muscle hypertrophy and trabeculation, and transmission of the high pressure into the upper urinary tracts, causing hydronephrosis (Fig. 536-2). Vesicoureteral reflux and UTI compound the problem. Treatment includes reduction of bladder pressure with anticholinergic drugs (oxybutynin, 0.2 mg/kg/24 hr in 2 or 3 divided doses) and clean intermittent catheterization every 3-4 hr. If there is vesicoureteral reflux or UTI, antimicrobial prophylaxis also is prescribed.

Urinary Incontinence

Complications

Metabolic Acidosis

The enteric mucosal surface in contact with the urine absorbs ammonium, chloride, and hydrogen ions and loses potassium. Hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis can result, possibly requiring medical treatment (Chapter 52); this condition can occur with colocystoplasty but rarely with ileocystoplasty. Chronic acidosis can compromise skeletal growth. Metabolic acidosis is most common in patients with compromised renal function and in those in whom colon has been used to enlarge the bladder. To overcome this limitation of enterocystoplasty in patients with chronic renal insufficiency, a composite augmentation using stomach and small or large bowel gastric segment can be used. The stomach secretes chloride and hydrogen ions; thus, pre-existing metabolic acidosis remains stable or improves.

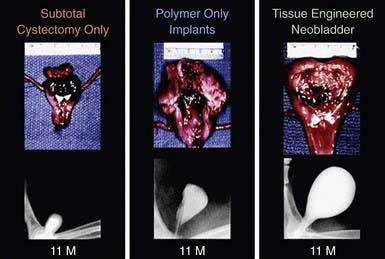

Future Management

The development of a tissue-engineered bladder using a composite scaffold, which could be attached to the dome of the bladder to increase capacity and compliance, might help patients achieve continence (Fig. 536-3). In addition, a nerve-rerouting procedure has the dorsal nerve root from the lumbar nerve sutured to the ventral sacral nerve root, thus controlling bladder function. The procedure allows the child to scratch the thigh to stimulate a bladder contraction.

Associated Disorders

Latex Allergy

Latex allergy (Chapter 143) is a very serious problem encountered by as many as half of patients with spina bifida and other urologic conditions who require clean intermittent catheterization and urinary tract reconstructive procedures. This IgE-mediated allergy is acquired and is secondary to repeated exposure to the latex allergen. Latex allergy can manifest as watery eyes, sneezing, itching, hives, or anaphylaxis when blowing up a balloon or if an examiner is using latex gloves. Intraoperatively, a sensitized patient can experience anaphylactic shock. A latex-free environment should be provided for all children with spina bifida in the office, during hospitalization, and during operative procedures. Affected children also should wear a medical alert bracelet.

Occult Spinal Dysraphism

Approximately 1/4,000 patients have occult spinal dysraphism, a category that includes lipomeningocele, intradural lipoma, diastematomyelia, tight filum terminale, dermoid cyst-sinus, aberrant nerve roots, anterior sacral meningocele, and cauda equina tumor (Chapter 585). More than 90% of patients have a cutaneous abnormality overlying the lower spine, including a small dimple, tuft of hair, dermal vascular malformation, or subcutaneous lipoma (Fig. 536-4). Often these children have high-arched feet, discrepancy in muscle size and strength between the legs, and a gait abnormality. Newborns and young infants often have a normal neurologic examination. Older children often have absent perineal sensation and back pain. Lower urinary tract function is abnormal in 40% of patients, including incontinence, recurrent UTI, and fecal soiling. The likelihood of a normal examination is inversely related to the child’s age at surgical correction of the spinal lesion. In infants with abnormal urodynamics, 60% revert to normal; in older children, only 27% become normal. Management of the urinary tract in other children is similar to that described earlier for neural tube defects.

Imperforate Anus

About 30-45% of children with a high imperforate anus have a neuropathic bladder, often because of sacral agenesis. Newborns with imperforate anus should undergo a spinal ultrasound during their initial evaluation, and if these children have difficulty with toilet training, complete urologic evaluation with upper and lower urinary tract imaging and urodynamics should be performed. See Chapter 336 for further details.

Cerebral Palsy

Children with cerebral palsy (Chapter 591.1) have reasonable bladder control. However, they achieve continence at a later age than unaffected children. Overall, 25-50% are incontinent, and the risk is directly related to the severity of physical impairment. Their upper urinary tracts usually are normal. Urodynamic studies have shown that most have uninhibited bladder contractions. Timed voiding and anticholinergic therapy are usually effective. Clean intermittent catheterization rarely is necessary.

Atala A. Bioengineered tissues for urogenital repair in children. Pediatr Res. 2008;63:569-575.

Atala A. Regenerative medicine and tissue engineering in urology. Urol Clin North Am. 2009;36:199-209.

Bowman RM, Mohan A, Ito J, et al. Tethered cord release: a long-term study in 114 patients. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;3:181-187.

Castellan M, Gosalbez R, Perez-Brayfield M, et al. Tumor in bladder reservoir after gastrocystoplasty. J Urol. 2007;178:1771-1774.

Catti M, Lortat-Jacob S, Morineau M, et al. Artificial urinary sphincter in children—voiding or emptying? An evaluation of functional results in 44 patients. J Urol. 2008;180:690-693.

deJong TP, Chrzan R, Klihn AJ, et al. treatment of the neurogenic bladder in spina bifida. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:889-896.

Dodson JL, Furth SL, Hsaio CJ, et al. Health related quality of life in adolescents with abnormal bladder function: an assessment using the Child Health and Illness Profile—Adolescent Edition. J Urol. 2008;180:1846-1851.

Elder JS, Pippi Salle JS. Bladder outlet surgery for congenital incontinence. In: Gearhart JP, Rink RC, Mouriquand PDE, editors. Pediatric urology. ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010:761-774.

Hensle TW, Gilbert SM. A review of metabolic consequences and long-term complications of enterocystoplasty in children. Curr Urol Rep. 2007;8:157-162.

Johal NS, Hamid R, Aslam Z, et al. Ureterocystoplasty: long-term functional results. J Urol. 2008;179:2373-2375.

Kim BS, Atala A, Yoo JJ. A collagen matrix derived from bladder can be used to engineer smooth muscle tissue. World J Urol. 2008;26:307-314.

Kurzrock EA. Pediatric enterocystoplasty: long-term complications and controversies. World J Urol. 2009;27:69-73.

Metcalfe PD, Luerssen TG, King SJ, et al. Treatment of the occult tethered spinal cord for neuropathic bladder: results of sectioning the filum terminale. J Urol. 2006;176:1826-1829.

Neel KF, Soliman S, Salem M, et al. Bolulinum-A toxin: solo treatment for neuropathic noncompliant bladder. J Urol. 2007;178:2593-2597.

Rowe DE, Jadhav AL. Care of the adolescent with spina bifida. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:1359-1374.

Soergel TM, Cain MP, Misseri R, et al. Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder following augmentation cystoplasty for the neuropathic bladder. J Urol. 2004;172:1649-1651.

Thomas J, Elder JS: Management of neuropathic bladder in children, part 1 and 2. AUA Update Series, vol 26, lessons 17 and 18, 2007, pp 173–192.

Xiao CG, Du MX, Liu Z, et al. An artificial somatic-autonomic reflex pathway procedure for bladder control in children with spina bifida. J Urol. 2005;173:2112-2116.