Neoplasms that spread to the CNS

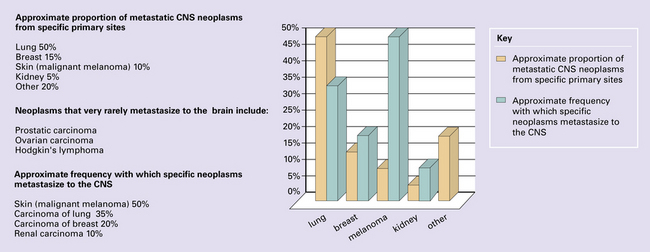

Primary neoplasms of the skull and spine may impinge upon the CNS, and (primary) neoplasms in other organs may metastasize to the CNS, its coverings, or its bony surroundings (Fig. 46.1).

Neoplasms that spread to the CNS, particularly intracerebral and intravertebral metastases, are common. Their reported incidence varies widely, and reflects whether authors have surveyed necropsy data or clinicopathologic data from centers that deal with different aspects of patient care (neurosurgery, radiotherapy, hospice care). The frequency of CNS metastasis also varies according to the site of primary neoplasm (Fig. 46.1).

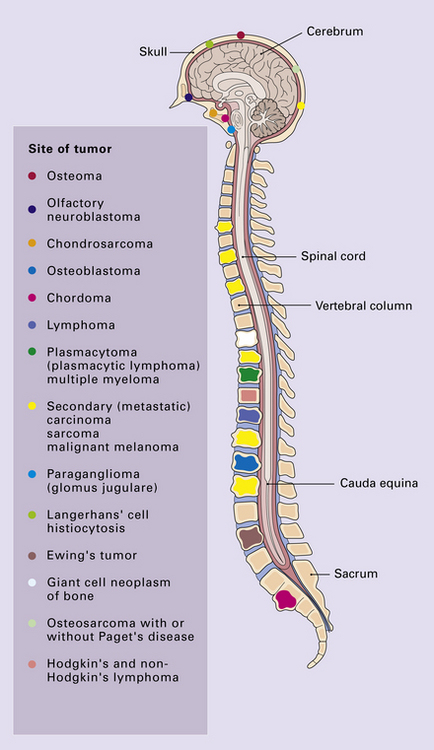

NEOPLASMS IN TISSUES SURROUNDING THE CNS

Primary and secondary neoplasms of the skull and spine produce symptoms and signs by destroying bone and compressing nervous system structures, either elements of the CNS or proximal cranial and spinal nerves (Fig. 46.2). Similar problems are caused on the occasions when mediastinal and retroperitoneal neoplasms invade the extradural space around the spinal cord.

Secondary carcinoma is the commonest neoplasm to impinge upon the CNS from surrounding structures, but other types of neoplasm at these sites behave similarly. Diagnosis is facilitated by consideration of the patient’s medical history, assessment of hematologic indices, and a range of imaging studies, in conjunction with histologic examination of biopsies (Figs 46.3–46.5).

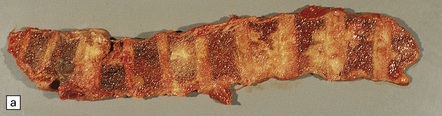

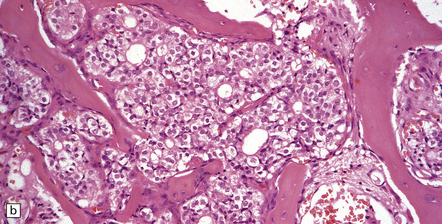

46.3 Metastatic carcinoma in the spine.

(a) Multiple deposits of metastatic carcinoma are present in the vertebrae. A tumor mass may extend from the bone to compress the spinal cord, but more commonly the pathology causes collapse of the vertebra, which itself compresses the cord. (b) This shows a vertebral deposit of adenocarcinoma from a primary tumor in the prostate gland, which presented with cord compression. An acinar architecture is evident. Common secondary carcinomas in the spine are from primary sites in the breast, lung, and prostate gland. Prostatic carcinoma that has metastasized to bone is commonly osteoblastic, in contrast to metastases from other carcinomas, which tend to be osteolytic. If the origin of a metastatic carcinoma is unknown, immunohistochemistry should be used, along with imaging studies, to investigate possible primary sites; this tumor was immunoreactive for prostatic specific antigen and prostatic acid phosphatase.

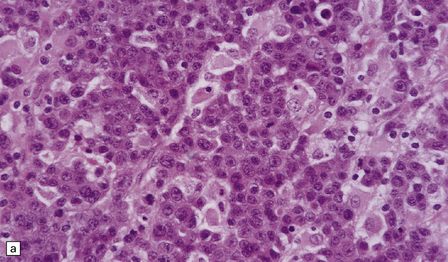

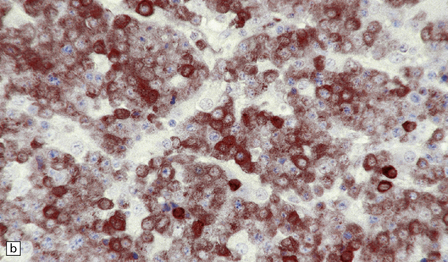

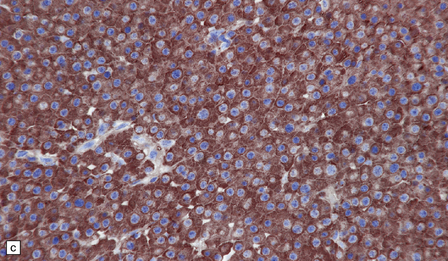

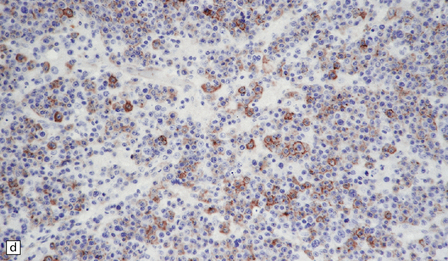

46.4 Plasmacytic lymphoma (plasmacytoma).

(a) This lymphoreticular neoplasm shows plasma cell differentiation and, in this case, was a solitary lesion in the spine, causing local pain and compression of CNS structures. About 50% of solitary osseous plasmacytic lymphomas progress to multiple myeloma, which is the commonest primary neoplasm within bone to cause CNS symptoms. (b) This plasmacytic lymphoma labeled with an antibody to CD79a, a pan-B cell marker. (c) Light chain restriction can sometimes be demonstrated in plasmacytic lymphoma/multiple myeloma by immunohistochemistry. In this case, cells labeled with a λ antibody (as shown here), but not a κ antibody. In situ hybridization for light chain mRNA is an alternative method for demonstrating clonality. (d) Plasmacytic lymphoma may rarely react with antibodies to epithelial membrane antigen (as shown here), leading potentially to an erroneous diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma. Normal plasma cells are immunoreactive for EMA. CD79a antibodies are helpful in this situation because they should not label carcinomas. With low-grade lymphoid neoplasms comprising well differentiated cells, the issue of whether the pathology is neoplastic or inflammatory sometimes arises. In this situation, establishing immunophenotype or the presence of tumor cell clonality will assist the diagnosis, along with other investigations, such as plasma electrophoresis.

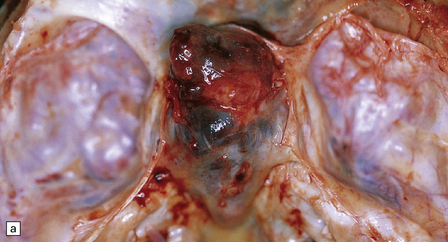

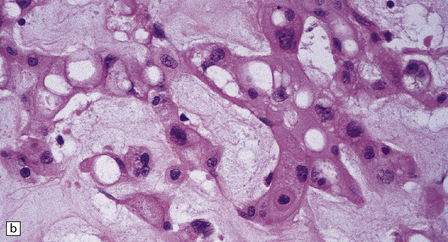

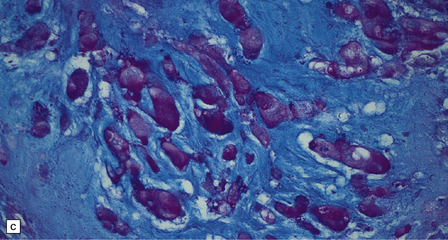

46.5 Chordoma.

About 80% of chordomas arise in the sacrum or the clivus, growing slowly into the spinal canal or base of the brain respectively. (a) This clival chordoma extends into the pituitary fossa and presented with visual field defects and pituitary dysfunction. The foci of dark gray-brown discoloration are due to hemorrhage at the time of biopsy. (b) The neoplasm consists of strands of cells with vacuolated cytoplasm (physaliphorous cells). (c) The neoplastic cells contain abundant glycogen, stained here with PAS, and are surrounded by a matrix of mucinous, alcianophilic material. A chondrosarcoma may arise in the sacrum or clivus, behaving like a chordoma and showing similar histopathological features. Immunoreactivity for cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen can be demonstrated in the cells of a chordoma, but not in the cells of a chondrosarcoma. Immunoreactivity for S-100 protein, which is characteristic of chordomas, helps to differentiate chordoma from metastatic adenocarcinoma.

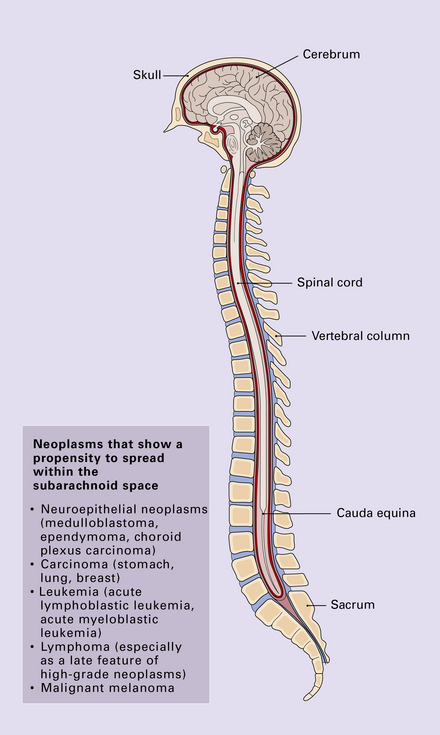

SECONDARY NEOPLASMS IN THE MENINGES

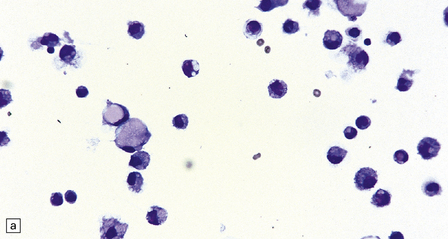

Secondary neoplasms in the meninges may form discrete nodules, or be disseminated within CSF pathways (Fig. 46.6). Nodules of neoplasm compress underlying CNS tissue, producing focal symptoms and signs, including epilepsy. Neoplasms that diffusely invade the subarachnoid space tend to produce hydrocephalus and raised intracranial pressure, by blocking CSF drainage. Cranial nerve palsies are also a common manifestation of this process. Cytologic examination of CSF is often diagnostic (Fig. 46.7). More than one sample is sometimes required to demonstrate neoplastic cells in the CSF. Occasionally, biopsy of the meninges is required.

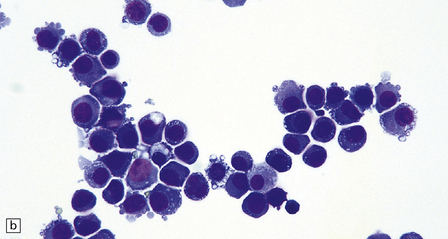

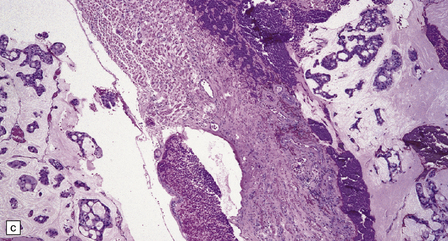

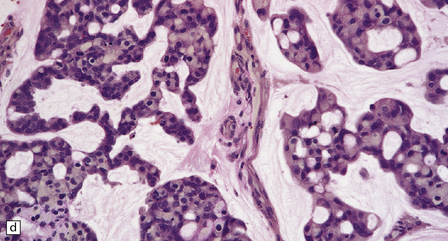

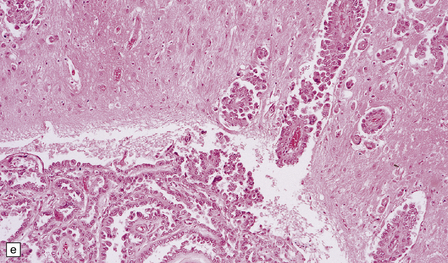

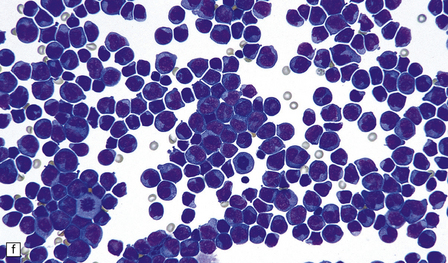

46.7 Metastatic neoplasms in the leptomeninges.

(a) Signet ring cells are present in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in this example of spread to the leptomeninges from an adenocarcinoma of the stomach. (b) Disseminated breast carcinoma has invaded the CSF pathways. There are clumps of pleomorphic cells with hyperchromatic nuclei in the CSF. One cell clearly contains intracytoplasmic mucin. (c) Metastatic carcinoma of breast in the leptomeninges around the spinal cord, surrounding a spinal nerve root. (d) Higher magnification discloses abundant mucin around and within the cells. (e) In this example of metastatic carcinoma in the cerebral leptomeninges, there is invasion of the superficial cerebral cortex along perivascular spaces. (f) Meningeal involvement by acute myeloid leukemia.

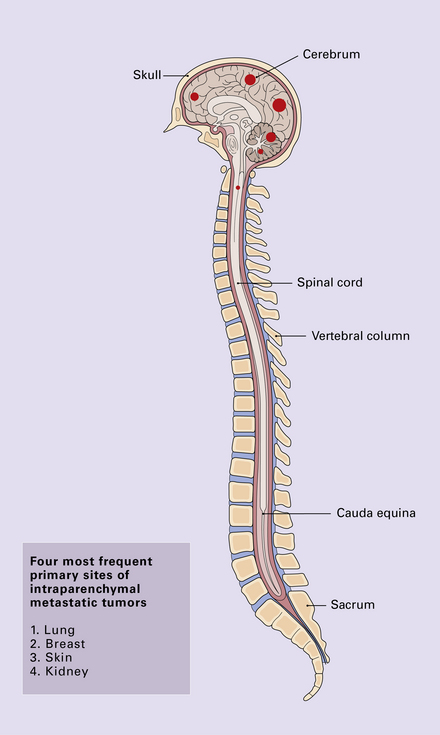

SECONDARY NEOPLASMS IN THE BRAIN AND SPINAL CORD

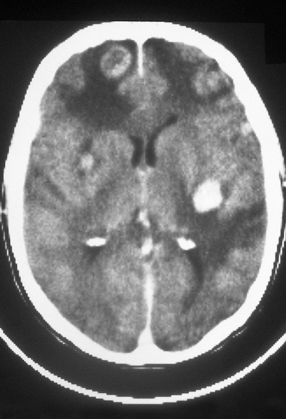

Solitary or multiple deposits of secondary neoplasm (Figs 46.8–46.13) may occur in the parenchyma of the CNS and can present with symptoms and signs of raised intracranial pressure, focal neurologic deficit, and epilepsy. Secondary carcinomas from primary sites in the lung and breast are commonest (Fig. 46.8). Neoplasms that show a particular tendency to spread to the CNS, such as malignant melanoma (see Fig. 46.1), usually present with multiple deposits (Fig. 46.9).

46.9 Metastatic malignant melanoma in the cerebrum.

Neuroimaging shows several contrast-enhancing masses surrounded by edema. (Courtesy of Dr J S Millar, Wessex Neurological Centre, UK.)

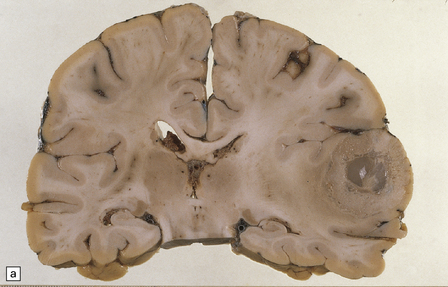

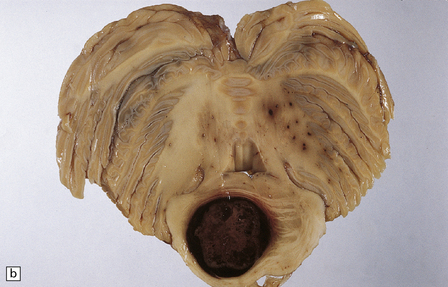

46.10 Metastatic neoplasms within the brain.

(a) A solitary metastasis in the right temporal lobe is associated with edema and midline shift. The center of the neoplasm is necrotic. The primary site was bronchus. (b) A hemorrhagic metastatic neoplasm in the pons. This is an unusual site for a metastasis; approximately 2% of metastases are in the brain stem.

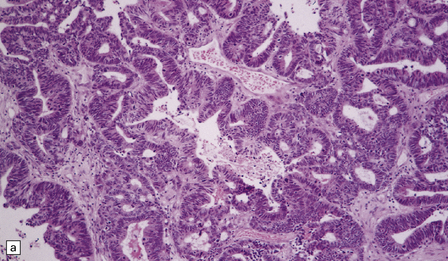

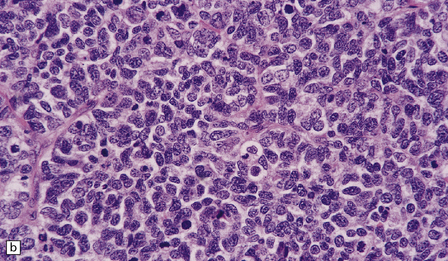

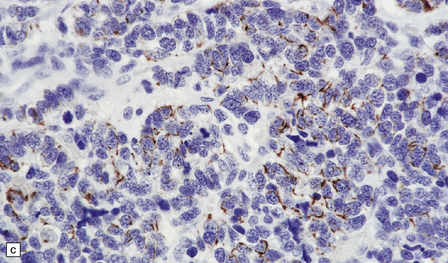

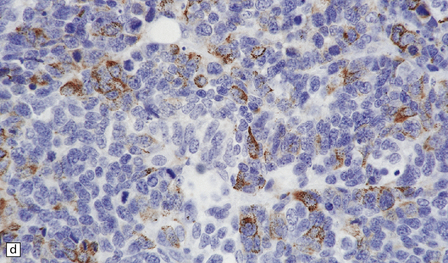

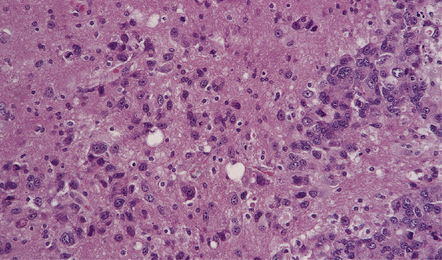

46.11 Metastatic neoplasms within the CNS.

(a) Glandular structures are a feature of this metastatic adenocarcinoma. Cytologic atypia and mucin are present. The primary site was the colon. (b) This metastatic small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) is composed of small round and oval cells. Its cytology and the presence of frequent mitoses and apoptotic bodies resemble the histopathologic features of a PNET, from which SCLC may be distinguished by its immunoreactivities for low molecular weight cytokeratins (c) and chromogranin (d). Patients with metastatic SCLC or carcinoma with neuroendocrine features often have no history of a primary neoplasm. Even imaging studies may initially fail to reveal the primary tumor. It is important to recognize that these neoplasms enter the differential diagnosis of PNET in adult patients.

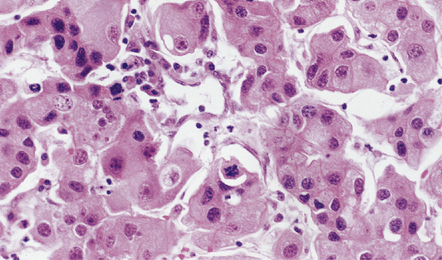

46.12 Poorly differentiated metastatic carcinoma invades brain.

Though most metastatic neoplasms are sharply demarcated from brain tissue, malignant melanomas and some poorly differentiated carcinomas, particularly those with a neuroendocrine immunophenotype, may show diffuse infiltration and mimic diffuse gliomas. Immunoreactivity for epithelial markers, such as cytokeratins, clearly defines metastatic carcinomas, but a metastatic malignant melanoma shares S-100 protein immunoreactivity with gliomas, some of which may not contain GFAP-immunopositive cells. Immunohistochemistry with the HMB-45 antibody, which labels cells in most malignant melanomas, or electron microscopy is helpful in this situation.

46.13 Metastatic carcinoma of the breast in the pituitary gland.

Rarely, metastatic neoplasms lodge in the stalk of the pituitary or in the neurohypophysis. Well differentiated carcinomas, particularly those from a primary site in the breast, share some cytologic features with pituitary adenomas, but do not have the pituitary adenoma’s synaptophysin-positive immunophenotype or any immunoreactivity for pituitary peptides.

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Neoplastic deposits may occur anywhere, but are relatively rare in the brain stem and spinal cord (Fig. 46.10). Watershed areas and the gray/white matter interface in the cerebrum are typical sites. Metastatic neoplasms generally form spherical masses in the brain, and surrounding edema is evident. The deposits may be firm or have a soft, mucoid, or necrotic center. Hemorrhage into the neoplasm is most characteristic of malignant melanoma or choriocarcinoma, and is not uncommon in metastatic renal carcinoma (the commonest primary neoplasm to present with hemorrhage is the oligodendroglioma). Intraparenchymal foci of hemorrhage in association with intravascular and perivascular neoplastic cells are a rare feature of leukemia. Malignant melanoma may show obvious pigmentation.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The edge of the neoplasm is usually well demarcated from adjacent brain, which generally contains reactive astrocytes, variable edema, and in some cases, inflammation. Occasionally, secondary neoplasms invade the brain diffusely, mimicking a primary neoplasm; malignant melanoma and poorly differentiated carcinoma are most often responsible (Fig. 46.12). Specific morphophenotypes and immunophenotypes allow the pathologist to establish a likely primary site for the neoplasm, but a firm diagnosis may be impossible.

Metastatic carcinoma is occasionally encountered in the stalk of the pituitary gland, often from a primary neoplasm in the breast (Fig. 46.13). This should not be confused with squamous metaplasia, which often occurs in this part of the pituitary gland (see Chapter 44).

REFERENCES

Becher, M.W., Abel, T.W., Thompson, R.C., et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of metastatic neoplasms of the central nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.. 2006;65:935–944.

Gavrilovic, I.T., Posner, J.B. Brain metastases: epidemiology and pathophysiology. J Neurooncol.. 2005;75:5–14.

Oien, K.A. Pathologic evaluation of unknown primary cancer. Semin Oncol.. 2009;36:8–37.

Olson, M.E., Chernik, N.L., Posner, J.B. Infiltration of the leptomeninges by systemic cancer. A clinical and pathologic study. Arch Neurol.. 1974;30:122–137.

Patchell, R.A. Brain metastases. Neurol Clin.. 1991;9:817–824.

Posner, J.B., Chernik, N.L. Intracranial metastases from systemic cancer. Adv Neurol.. 1978;19:579–592.

Russell, D.S., Rubinstein, L.J. Secondary tumors of the nervous system. Pathology of tumours of the nervous system, 5th ed. London: Edward Arnold; 1989.