Neoplasms of the pineal gland

PINEAL PARENCHYMAL NEOPLASMS

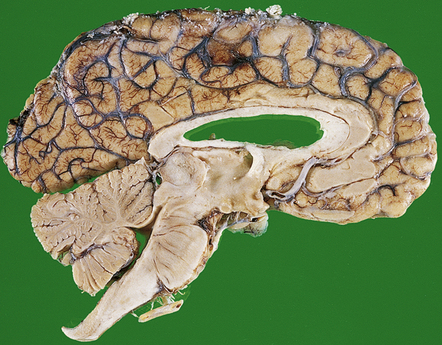

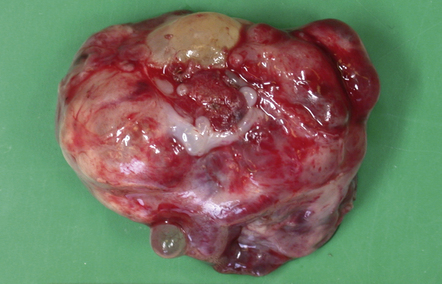

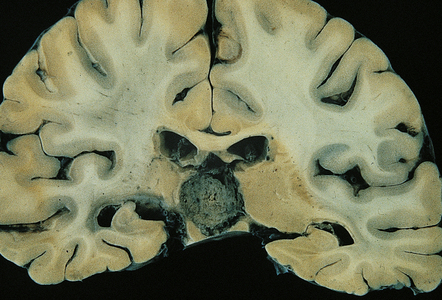

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Pineocytomas are firm gray neoplasms. Pineoblastomas are softer and sometimes gelatinous in texture and may contain areas of hemorrhage and necrosis. Although both types of neoplasm may be circumscribed, pineocytomas usually compress surrounding tissues (Fig. 39.1), while pineoblastomas tend to infiltrate the midbrain, third ventricle, or sometimes the thalamus and hypothalamus. Pineoblastomas frequently disseminate throughout the CNS along CSF pathways.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

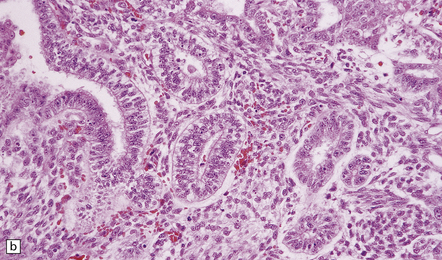

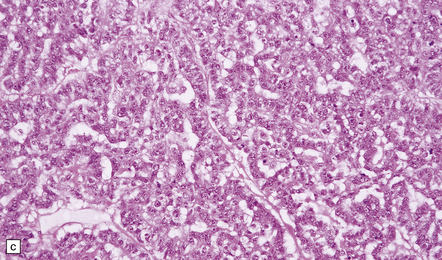

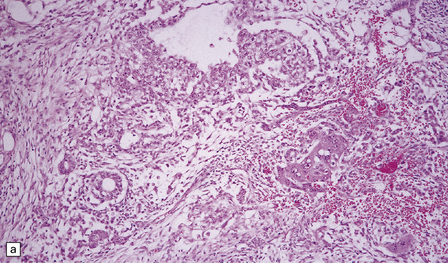

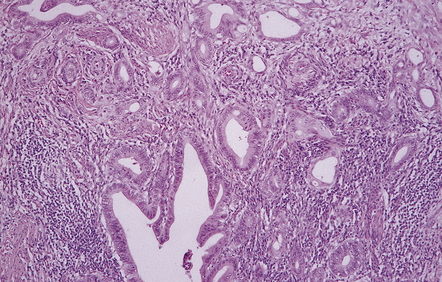

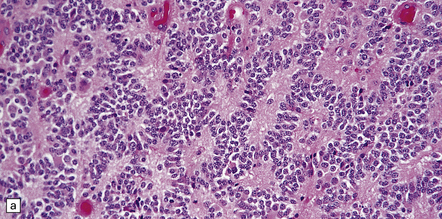

Pineocytoma

The pineocytoma consists predominantly of small monomorphic cells set in a fibrillary background (Fig. 39.2). The cells are generally arranged in sheets, though a nodular pattern may occasionally be evident. A characteristic feature is the formation of pineocytomatous rosettes, which are relatively large zones of fine, fibrillary processes surrounded by an oval arrangement of neoplastic cell nuclei (see Fig. 39.5). The neoplastic cells generally resemble the cells of normal pineal gland, with their argyrophilic processes which may have club-like terminal expansions. Their processes express NSE and synaptophysin, and at the ultrastructural level contain microtubules and a few dense core vesicles. Some cells label with antibodies to S antigen.

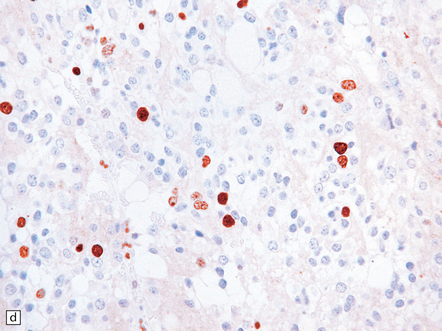

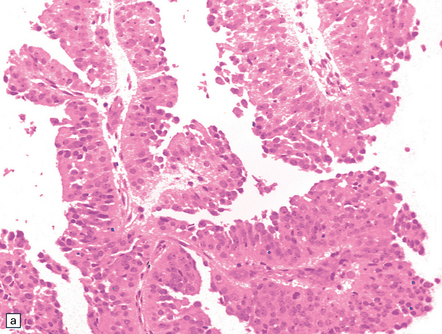

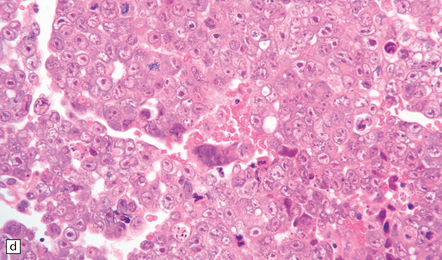

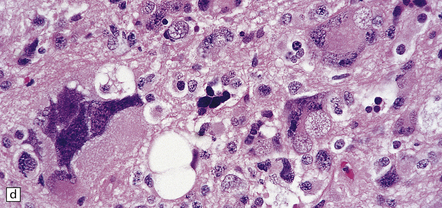

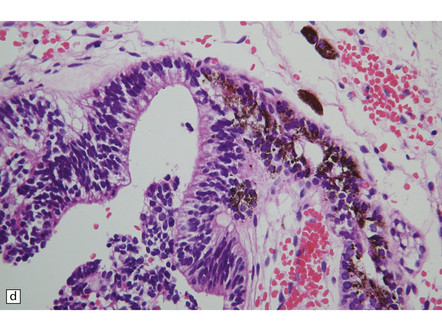

39.2 Pineocytoma.

(a) Pineocytomatous rosettes dominate this region of a typical pineocytoma. (b) In a smear preparation, the cells of this pineocytoma are characterized by uniformity, delicate cytoplasmic processes, and tiny nucleoli. (c) Silver impregnation of the neuritic processes in a pineocytomatous rosette. (d) Cytologic pleomorphism as marked as here may be seen in pineocytomas and intermediate pineal parenchymal neoplasms. In an otherwise typical pineocytoma with pineocytomatous rosettes, but without mitoses and focal increases in nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio, it is not thought to be an adverse prognostic sign. (e) Widespread immunoreactivity for neurofilament proteins is typical of pineocytomas.

Intermediate or mixed pineal parenchymal neoplasms

The pineal parenchymal tumor of intermediate differentiation is characterized by a syncytial or occasionally lobular architecture (Fig. 39.3). Some of its cells may resemble those of a pineocytoma, but it lacks the well-differentiated features of this tumor, including pineocytomatous rosettes. Collections of ‘blast’ cells are also missing. Cytologic pleomorphism is variable, but usually not marked. Mitoses are readily found. Ganglion cells and giant cells are occasionally evident. Immunoreactivity for neuronal markers may be prominent. This variant sometimes metastasizes throughout the CNS. Indicators of a more favorable outcome among intermediate tumors are immunoreactivity for neurofilament proteins, and a mitotic count of less than 6/10 hpfs.

The pineal parenchymal tumor of intermediate differentiation is characterized by a syncytial or occasionally lobular architecture (Fig. 39.3). Some of its cells may resemble those of a pineocytoma, but it lacks the well-differentiated features of this tumor, including pineocytomatous rosettes. Collections of ‘blast’ cells are also missing. Cytologic pleomorphism is variable, but usually not marked. Mitoses are readily found. Ganglion cells and giant cells are occasionally evident. Immunoreactivity for neuronal markers may be prominent. This variant sometimes metastasizes throughout the CNS. Indicators of a more favorable outcome among intermediate tumors are immunoreactivity for neurofilament proteins, and a mitotic count of less than 6/10 hpfs.

The rare mixed pineocytoma/pineoblastoma is characterized by groups of small, rapidly proliferating cells in a neoplasm which otherwise has the architecture and cytology of a pineocytoma. The small ‘blast’ cells confer the behavioral properties of a pineoblastoma upon this neoplasm.

The rare mixed pineocytoma/pineoblastoma is characterized by groups of small, rapidly proliferating cells in a neoplasm which otherwise has the architecture and cytology of a pineocytoma. The small ‘blast’ cells confer the behavioral properties of a pineoblastoma upon this neoplasm.

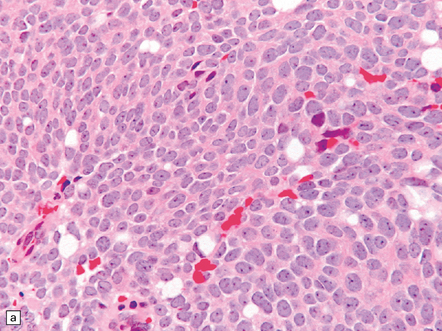

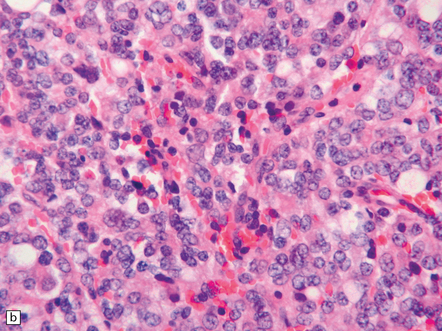

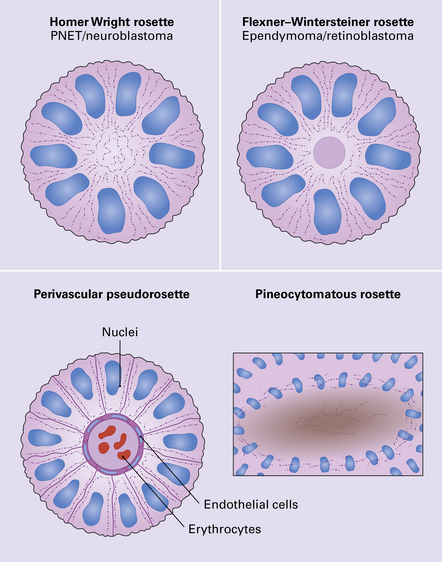

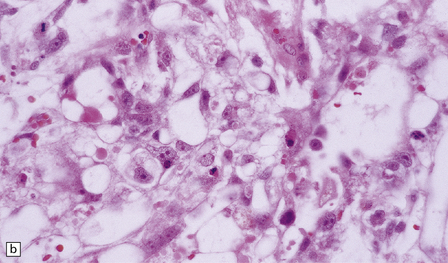

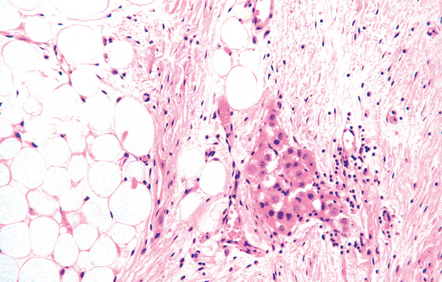

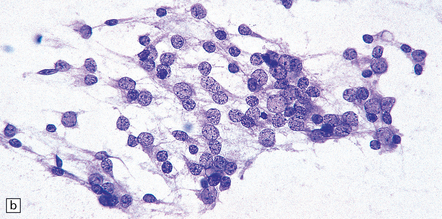

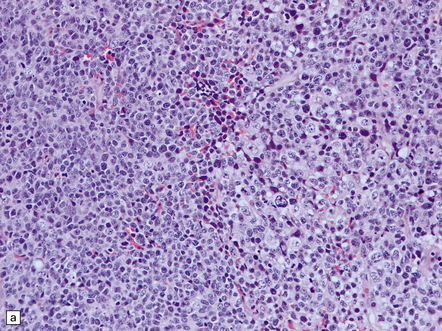

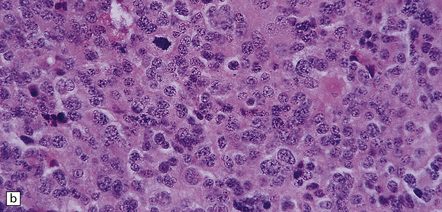

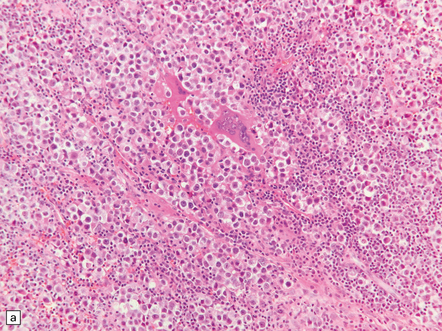

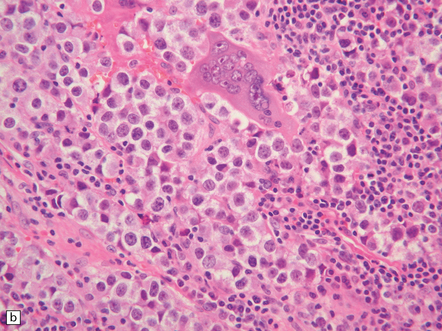

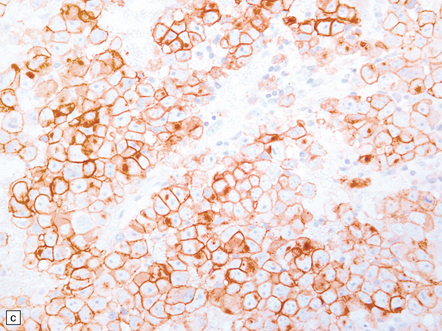

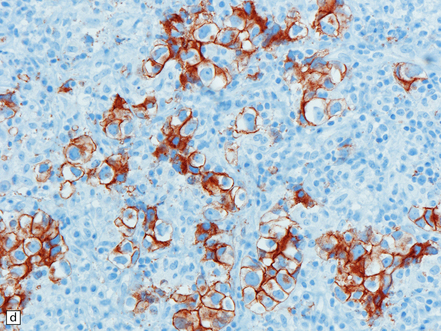

Pineoblastoma

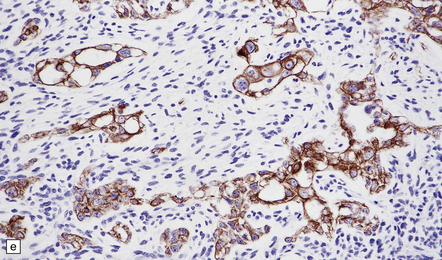

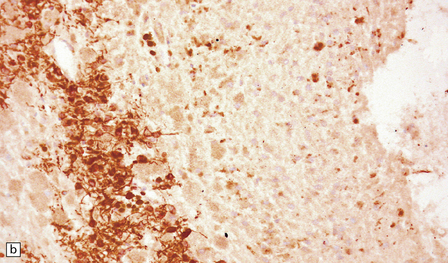

The pineoblastoma resembles the classic (non-desmoplastic) medulloblastoma, and was previously grouped with other embryonal neoplasms of neuroepithelial lineage in the broad category of primitive neuroectodermal tumors (Chapter 38). It contains round or polyhedral cells with a high nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio, which are arranged in sheets or lobules (Fig. 39.4). Mitoses and apoptotic bodies are generally plentiful. Neuroblastic (Homer Wright) and Flexner–Wintersteiner rosettes may occasionally be found, but pineocytomatous rosettes are not a feature of the typical pineoblastoma (Fig. 39.5), being found only in the rare mixed tumor. Necrosis and hemorrhage are common, while melanin-producing cells or signs of mesenchymal differentiation, such as striated muscle or cartilage, are exceptional. Immunoreactivity for neuronal markers may be local or widespread (Fig. 39.4), and pineoblastomas may label with antibodies to retinal S antigen.

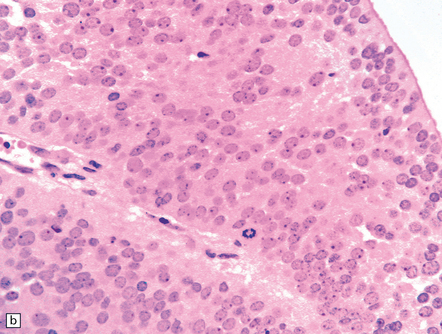

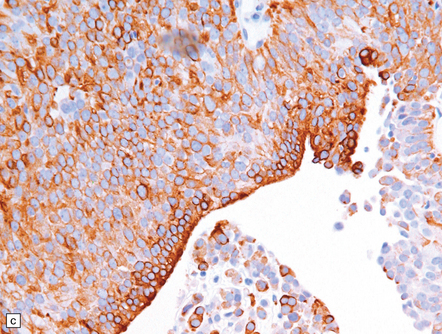

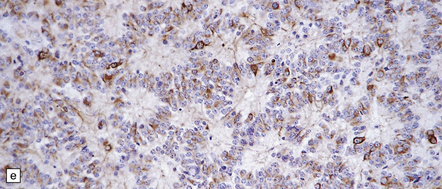

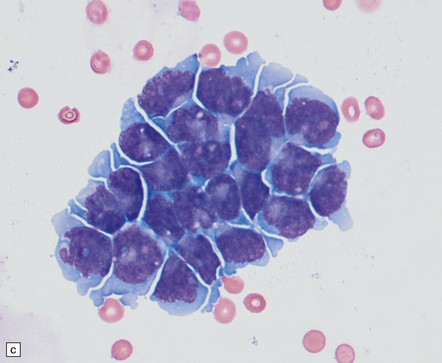

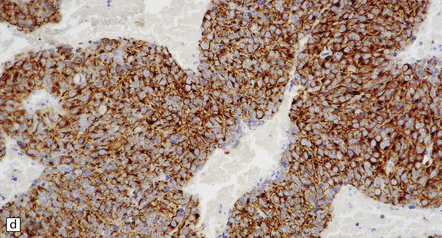

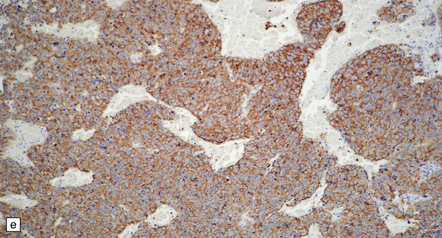

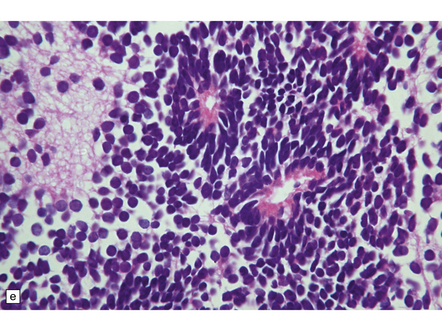

39.4 Pineoblastoma.

(a,b) Monomorphic round cells with a high nuclear:cytoplasmic ration and variably hyperchromatic nuclei are evident. Mitotic figures are readily found. (c) The tumor has a propensity to disseminate within CSF pathways; this clump of cells was detected in lumbar CSF in a patient with several metastatic deposits in the spinal meninges. Lobules of neoplastic cells have labeled with antibodies (d) to neurofilament protein, and (e) to synaptophysin.

PAPILLARY TUMOR OF THE PINEAL REGION

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The tumor exhibits papillary projections or a syncytial pattern and consists of epithelioid cells, which may be cuboidal or columnar (Fig. 39.6). Cytoplasmic clearing is occasionally found. Rosette formation, either Homer Wright or Flexner–Wintersteiner, may be evident. Mitotic activity is generally low, but can rise to moderate levels in some regions.

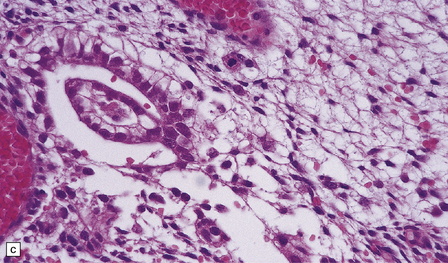

PINEAL CYST

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

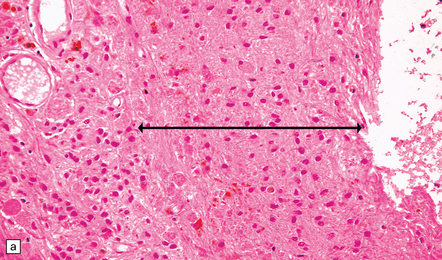

The pineal cyst has a thin wall typically composed of three layers; a fibrous outer layer, a rim of pineocytes and an inner layer of glial tissue containing Rosenthal fibers (Fig. 39.7). Reactive astrocytes of the inner rim have a variable nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio, and may show an atypia that is degenerative. Surrounding pineal gland may appear compressed.

39.7 Pineal cyst.

(a) The cyst cavity (right) is lined by a layer of gliotic tissue (arrow), around which a rim of pineocytes is evident (left). (b) The pineocytes are immunopositive for neurofilament proteins. (c) In this part of the cyst wall, astrocytic gliosis entraps pineocytes. Rosenthal fibers and dystrophic calcification are frequently found.

PRIMARY CNS GERM CELL NEOPLASMS

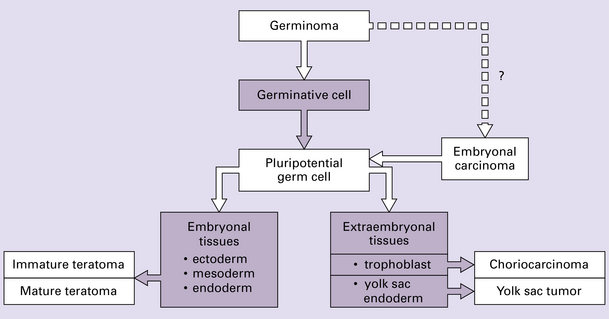

The pathology and biology of CNS GCTs are very similar to those of gonadal GCTs. Indeed, the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of GCTs at the different sites listed above is the same, the terms seminoma (testis), dysgerminoma (ovary), and germinoma (CNS) being interchangeable. A germinoma must first be differentiated from a nongerminomatous GCT because germinomas are particularly sensitive to radiotherapy. Nongerminomatous GCTs range from slowly growing mature teratomas to undifferentiated neoplasms that grow and spread rapidly. GCTs recognized in the WHO classification of neoplasms of the CNS are germinomas, embryonal carcinomas, yolk sac tumors (endodermal sinus tumors), choriocarcinomas, teratomas (mature, immature, and with malignant transformation – usually carcinoma or sarcoma), and mixed GCTs (Fig. 39.8).

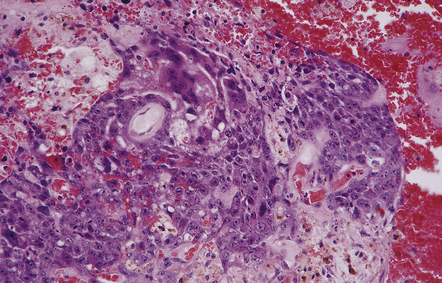

GERMINOMAS

Germinomas are generally soft, friable, and well-circumscribed masses (Fig. 39.9). Diffuse invasion of adjacent structures is unusual, but may occur, simulating a glioma. Cysts may be present.

39.9 Pineal germinoma.

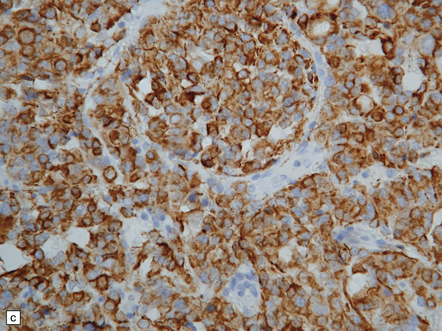

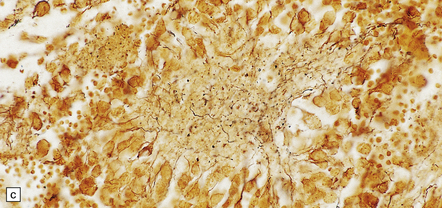

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

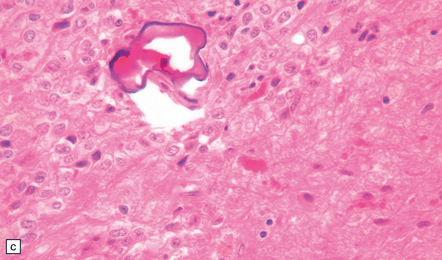

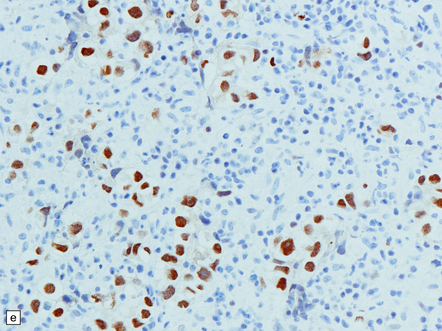

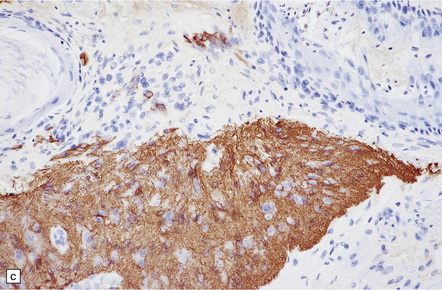

Pineal and suprasellar germinomas have the same histologic features as ovarian dysgerminomas and testicular seminomas. Groups of plump, round neoplastic cells with prominent nucleoli are surrounded by aggregates of reactive T lymphocytes, which may be numerous and distract the pathologist from the true nature of the pathology (Fig. 39.10). The neoplastic cells often have clear, glycogen- rich cytoplasm. They label with antibodies to placental alkaline phosphatase in all but about 5% of cases, and sometimes with antibodies to cytokeratins. Immunoreactivity for CD117 is detected in many germinomas and is specific for this tumor among GCTs. OCT4 is almost always expressed by germinomas, but embryonal carcinomas may also be OCT4-positive. Granulomatous inflammation may be seen, and in small biopsies can cause confusion with sarcoidosis and tuberculosis.

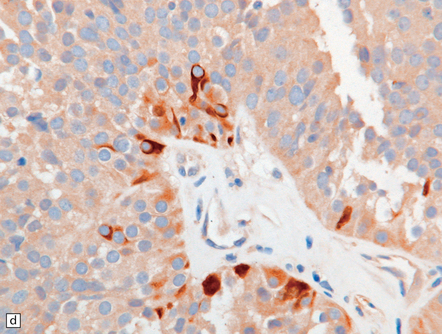

39.10 Germinoma.

(a,b) Sheets of large cells, many with cytoplasmic clearing and prominent nucleoli, are divided by fibrous septa and admixed with a lymphocytic infiltrate. A few syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells may be present and are immunoreactive for β-HCG. Tumor cells in germinomas may demonstrate immunoreactivity for placental alkaline phosphatase (c), CD117 (d), or OCT4 (e).

EMBRYONAL CARCINOMA, YOLK SAC TUMOR, AND CHORIOCARCINOMA

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Embryonal carcinoma

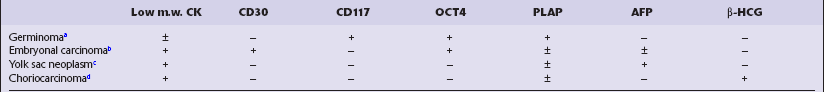

This appears microscopically as sheets of large, moderately pleomorphic cells with a glandular, cribriform, papillary or solid arrangement. Clear cytoplasm may be a feature of some cells. Mitoses and necrosis are evident. Immunohistochemistry reveals reactivity for CD30 and OCT4, the latter a feature shared with germinoma. There is also scattered reactivity for low molecular weight cytokeratins (Fig. 39.11), and cells may occasionally label with antibodies to placental alkaline phosphatase, β-HCG, and AFP (Table 39.1).

Table 39.1

Immunohistochemistry of germ cell tumors

aGiant syncytiotrophoblastic cells show immunoreactivity with antibodies to β-HCG.

bNo immunoreactivity with antibodies to vimentin.

cVery rare immunoreactivity with antibodies to CD117.

dSyncytiotrophoblastic cells show immunoreactivity with antibodies to human placental lactogen.

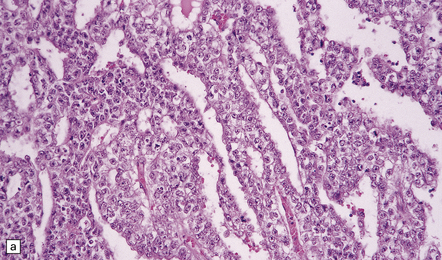

Yolk sac tumor

Cells in a yolk sac tumor are usually arranged in a loose or lacy pattern and may have clear cytoplasm. Solid, glandular and trabecular patterns occasionally occur. Dark pink globules termed eosinophilic bodies are frequent, and the characteristic Schiller–Duval bodies may be found (Fig. 39.12). Eosinophilic bodies are PAS-positive and often contain AFP immunoreactivity. Yolk sac tumor is generally less pleomorphic than embryonal carcinoma.

TERATOMAS

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

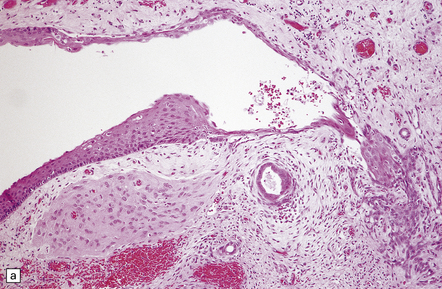

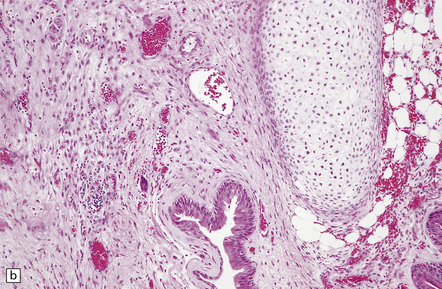

Differentiated teratomas are well circumscribed and usually have a lobulated or partly cystic appearance (Fig. 39.14). They may contain a mixture of tissues derived from three embryonic cell lines (i.e. ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm). Mature teratomas contain only adult tissues (Fig. 39.15), while embryonic tissues predominate in immature teratomas. Disorganized embryonic neuroepithelial tissue is commonly seen, often as a cluster of rosettes. Malignant transformation of a mature teratoma to carcinoma (Fig. 39.16), sarcoma, or even primitive neuroectodermal tumor may rarely occur. The term ‘mixed germ cell tumor’ encompasses any combination of the GCTs described above (Fig. 39.17). The recognition of mixed elements is clinically important, determining strategy for adjuvant therapy.

39.15 Teratoma.

(a) and (b) A variety of mature tissue types may be present, including (c) neuroepithelial tissue that is immunoreactive for GFAP and (d) retina with adjacent pigmented epithelium. (e) Immature tissues in teratomas are often neuroepithelial, as here, demonstrating two rosette structures among a group of undifferentiated cells.

REFERENCES

Bjornsson, J., Scheithauer, B.W., Okazaki, H., et al. Intracranial germ cell tumors: pathobiological and immunohistochemical aspects of 70 cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.. 1985;44:32–46.

Chang, S.M., Lillis-Hearne, P.K., Larson, D.A., et al. Pineoblastoma in adults. Neurosurgery.. 1995;37:383–391.

Cho, B.K., Wang, K.C., Nam, D.H., et al. Pineal tumors: experience with 48 cases over 10 years. Childs Nerv Syst.. 1998;14:53–58.

DeGirolami, U., Schmidek, H. Clinicopathological study of 53 tumors of the pineal region. J Neurosurg.. 1973;39:455–462.

Fain, J.S., Tomlinson, F.H., Scheithauer, B.W., et al. Symptomatic glial cysts of the pineal gland. J Neurosurg.. 1994;80:454–460.

Fèvre-Montange, M., Szathmari, A., Champier, J., et al. Pineocytoma and pineal parenchymal tumors of intermediate differentiation presenting cytologic pleomorphism: a multicenter study. Brain Pathol.. 2008;18:354–359.

Ho, D.M., Liu, H.C. Primary intracranial germ cell tumor. Pathologic study of 51 patients. Cancer.. 1992;70:1577–1584.

Horowitz, M.B., Hall, W.A. Central nervous system germinomas A. review. Arch Neurol.. 1991;48:652–657.

Jennings, M.T., Gelman, R., Hochberg, F., et al. Intracranial germ-cell tumors: natural history and pathogenesis. J Neurosurg.. 1985;63:155–167.

Jouvet, A., Saint-Pierre, G., Fauchon, F., et al. Pineal parenchymal tumors: a correlation of histological features with prognosis in 66 cases. Brain Pathol.. 2000;10:49–60.

Li, M.H., Bouffet, E., Hawkins, C.E., et al. Molecular genetics of supratentorial primitive neuroectodermal tumors and pineoblastoma. Neurosurg Focus.. 2005;19:E3.

Matsutani, M., Sano, K., Takakura, K., et al. Primary intracranial germ cell tumors: a clinical analysis of 153 histologically verified cases. J Neurosurg.. 1997;86:446–455.

O’Callaghan, A.M., Katapodis, O., Ellison, D.W., et al. The growing teratoma syndrome in a nongerminomatous germ cell tumor of the pineal gland: a case report and review. Cancer.. 1997;80:942–947.

Sano, K. Pathogenesis of intracranial germ cell tumors reconsidered. J Neurosurg.. 1999;90:258–264.

Scheithauer, B.W. Pathobiology of the pineal gland with emphasis on parenchymal tumors. Brain Tumor Pathol.. 1999;16:1–9.

Schild, S.E., Scheithauer, B.W., Schomberg, P.J., et al. Pineal parenchymal tumors. Clinical, pathologic, and therapeutic aspects. Cancer.. 1993;72:870–880.

Tapp, E., Huxley, M. The histological appearance of the human pineal gland from puberty to old age. J Pathol.. 1972;108:137–144.