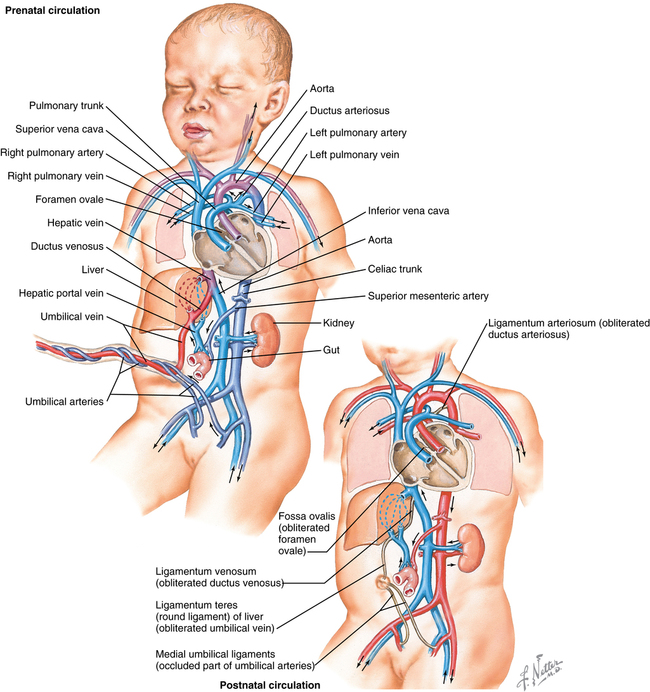

Compared with the postnatal circulation (in which the right ventricle and left ventricle are in series), in the fetal circulation, the two ventricles are in parallel. The parallel circulation is created by several shunts and preferential flow patterns that deliver relatively well-oxygenated blood from the placenta to those fetal organs that have increased metabolic demand. The most important structures that shunt blood in the fetal circulation are the ductus venosus (DV), the foramen ovale (FO), and the ductus arteriosus (DA).

From the placenta, blood with a partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) of 30 to 35 mm Hg flows to the fetus via the umbilical vein (UV) (Figure 191-1), which, in the liver of the fetus, separates into two branches, with one branch joining the portal vein and the other becoming the DV, which joins the inferior vena cava (IVC). Approximately 30% to 50% of the oxygenated blood flowing through the UV will bypass the liver and flow directly through the DV into the IVC, flowing along its posterior wall. As this oxygenated blood enters the right atrium, it is directed across the FO into the left atrium by the eustachian valve, flowing through the left ventricle (∼35% of fetal circulation) into the aorta to supply the head and upper torso.

The deoxygenated blood returning from the superior vena cava, from the myocardium via the coronary sinus, and from the IVC flows through the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery. Most of this deoxygenated blood returns to the descending aorta via the DA; however, approximately 5% to 10% passes through the high-resistance pulmonary circulation. Blood in the descending aorta either flows through the umbilical arteries to be reoxygenated in the placenta or continues to supply the lower limbs. The fetal circulation therefore runs in parallel, with the left ventricle providing 35% and the right 65% of cardiac output. Fetal cardiac output is therefore measured as a combined ventricular output (CVO).

The three major shunts are under autonomic, neural, and hormonal control. The DV, for example, is not a passive shunt; the vessel is trumpet-shaped, with a sphincter at its distal end that regulates flow by β-adrenergic dilation or α-adrenergic constriction. Hypoxemia, presumably via release of endothelial nitric oxide, results in significant vasodilation. Prostaglandins ostensibly have an important role, as they do in the DA, in maintaining patency and in closure following birth.

The second major shunt, the FO, provides a communication between the right and left atria, directing flow from the inferior venous inlet. As the stream of oxygenated blood ascends along the posterior wall of the IVC into the right atrium, it encounters the interatrial ridge, which separates into two arms. The left arm fills like a windsock formed by the FO valve and the atrial septum to direct the oxygenated blood through the FO into the left atrium. The right arm of the interatrial ridge directs deoxygenated blood toward the right atrium to join with the flow from the superior vena cava and coronary sinus to the tricuspid valve. Channeling of this blood flow is sensitive to a number of factors and is easily influenced by differences in systemic and pulmonary pressures.

The last shunt, the DA, is a wide muscular vessel that connects the pulmonary artery to the descending aorta. The majority of blood ejected from the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery crosses the DA and flows to the lower torso and umbilical arteries. A small fraction, anywhere between 5% and 10%, of the right ventricular output flows beyond the DA into the pulmonary circulation because, prior to birth and inflation of the lungs, the pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) is quite high because the alveoli are collapsed, compressing the interstitium of the lung. However small the fraction is, it is sufficient to meet the metabolic needs for development and growth of the lungs.

Fetal cardiac output increases from 210 mL/min at 20 weeks of gestation to 1900 mL/min at term. Two thirds of the total aortic flow goes to the placenta because the systemic vascular resistance (SVR) within the placental blood vessels is relatively low, compared with the resistance in the blood vessels within the fetal organs and tissues. Placental blood flow is relatively stable, unaffected by autonomic or neural inputs, correlating best with maternal arterial blood pressure.

The fetal ventricles are poorly compliant, with the right less so than the left, in part from the constraint of the pericardium, collapsed lungs, and constrained chest wall. They are therefore limited in their ability to increase stroke volume, so that an increase in cardiac output is achieved by an increase in heart rate. Conversely, if heart rate decreases, so too does cardiac output. Unlike during the postnatal state, in the prenatal state, there is very little difference between fetal right and left ventricular pressures.